Lewis and Clark were among several significant explorers of North America both before and after the expedition.

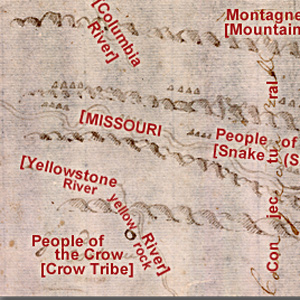

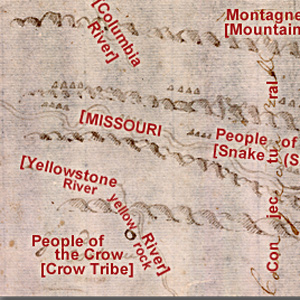

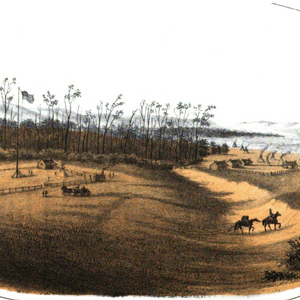

John Evans provided maps of the Missouri River and Rocky Mountains, the most significant outcome of the Mackay-Evans Expedition.

James Mackay

Showing the way

James Mackay provided the captains the most current and accurate map and information about the upper Missouri River available.

Daniel Boone was sixty-nine years old in 1803, too old to go traipsing out to the Pacific Ocean. But Lewis’s “qualifycations” suggest that Boone would have been precisely the kind of hunter he hoped to find.

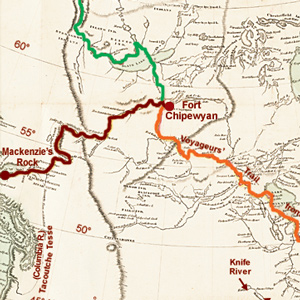

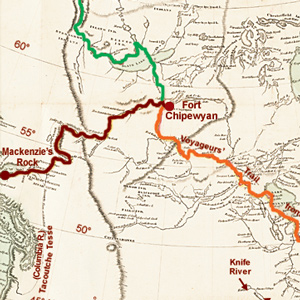

He was the first literate traveler to cross the North American continent north of Mexico, beating Meriwether Lewis and William Clark by nearly 12 years. The Lewis and Clark journals often echo Mackenzie’s journal.

Narrado tanto en inglés como en español, Daniel Flores narra la historia de una exploración paralela y sureña ahora casi olvidada.

Lt. John Mullan surveyed the Northern Nez Perce road across the Bitterroot Range in 1853-54 to assess its suitability as a railroad route. He never met anyone named Lolo, but was told by an Iroquois guide and interpreter that the creek was called the “Lo Lo Fork,” or “Lo Lo’s Fork.”

While Lewis and Clark wintered in North Dakota, Dunbar and Hunter explored the Ouachita River in Arkansas. They would alter Jefferson’s plans to explore the Red and Arkansas Rivers.

The life and times of these three explorers intertwined in a number of odd and interesting ways, often brought together by far-reaching hand of Thomas Jefferson. Tracing these connections opens a window onto every conceivable aspect of the period.

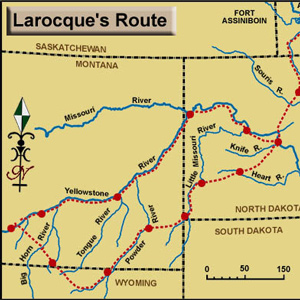

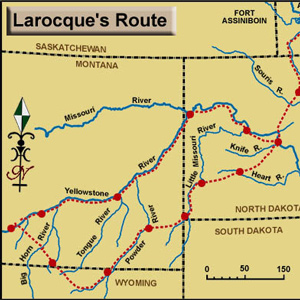

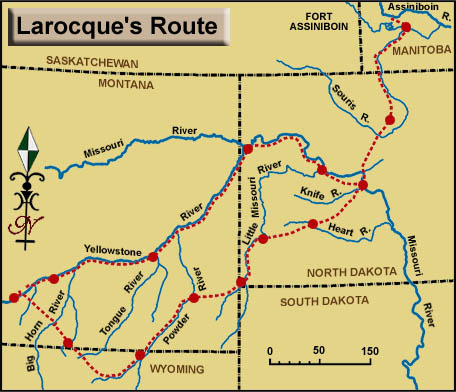

François-Antoine Larocque

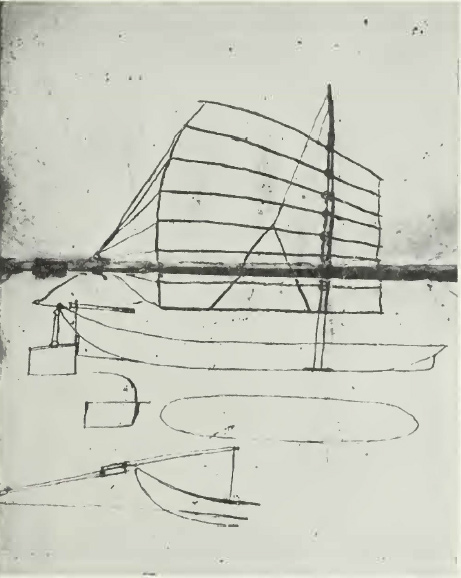

The fourth literate explorer to go up the Yellowstone (and before Clark) was François-Antoine Larocque, who is important to the story of Lewis and Clark on the Middle Missouri for several reasons.

Narrated in both English and Spanish, Daniel Flores tells the story of a parallel, southern exploration now nearly forgotten.

In 1792, André Michaux approached members of the American Philosophical Society informing his potential sponsors that he was “ready to go to the sources of the Missouri and even explore the rivers that flow into the Pacific Ocean.”

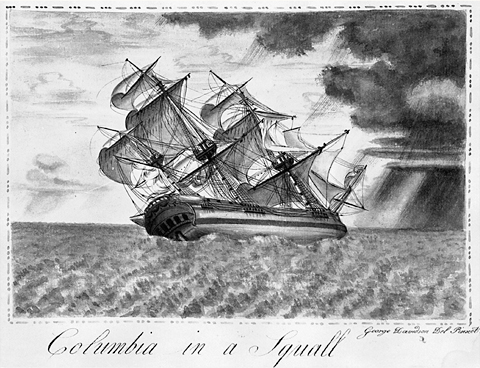

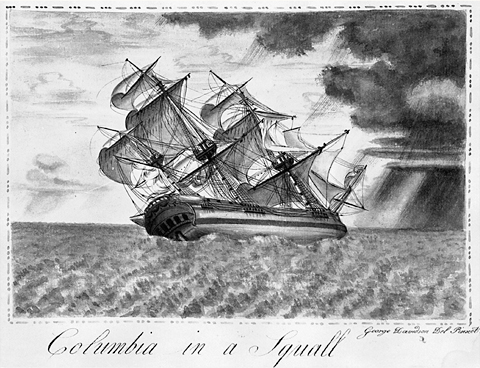

“the Ocian is imedeately in front and gives us an extensive view of it from Cape disapointment to Point addams,” reported William Clark on 15 November 1805. But he saw no ships at anchor. Nothing.

Like his contemporaries Lewis and Clark, Pike also provided information on flora and fauna and discovered several new species. His southern exploration paved the way for a viable route linking the United States and Santa Fe.

La Vérendrye’s 1728 name for Spirit Mound contains several puzzling statements. Pako’s reference to that “very fine gold-coloured sand,” suggests the “little mountain” was located in a fabulous land, an Eldorado, of precious natural riches.

Larocque’s Yellowstone Journey

One year before Clark

The fourth literate explorer to go up the Yellowstone (and before Clark) was François-Antoine Larocque, who is important to the story of Lewis and Clark on the Middle Missouri for several reasons.

The Corps of Discovery was but one of a great number of expeditions by land and sea made between 1770 and 1870 across the North American continent in search of a Northwest Passage. Lewis knew much about the mouth of the Columbia River.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.