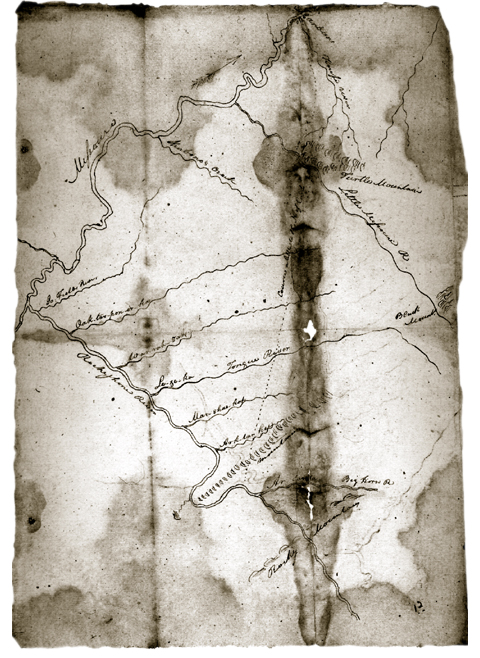

Pryor’s Intended Route

Pryor’s Intended Route

Elevation Model and Satellite Image from September 14, 2000

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2001 Jeff Silkwood, EOS Education Project, University of Montana

Compare the above image with the map Clark drew from Sheheke‘s information (below), and the Warren map of 1855, showing the “War Path of the Big Bellies.”

It is impossible to know which of two possible routes Pryor and his men would have followed back to the Knife River Villages.[1]Moulton’s Atlas map 116, shows “Sargent Pryors route with the Horses” as a short dotted line which, as he points out, roughly parallels the route of today’s Interstate 90. … Continue reading The land route down the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, which François-Antoine Larocque followed, would have would have been nearly 550 miles long, taking them through several stretches of badlands where travel would have been slow and dangerous. (Of course, Clark couldn’t have known that in advance.)

The “War Path of the Big Bellies [Hidatsas],” which is shown as a direct, straight line on Clark’s map of 1805, would have taken them over some low ranges of hills, such as the Little Wolf Mountains and the Pine Hills, and would have been only about 360 miles (580 km) long. So the shorter, straight-line route seems the more logical one.

Pryor’s Intelligence

During the winter at Fort Mandan, Clark drew a sketch from information provided by the Mandan chief, Sheheke (Big White), who dined with the captains on 7 January 1805, and gave him “a Scetch of the Countrey as far as the high mountains, & on the South side of the River Rejone [Roche Jaune; Yellowstone].” Clark added, “he Says that the river rejone recves 6 small rivers on the s. Side, & that the Countrey is verry hilley and the greater part Covered with timber, Great numbers of beaver &c.” Gary Moulton has concluded that some of the tributaries were added to the map after Clark covered the route in 1806.[2]Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b.

The comprehensive map Clark compiled at Fort Mandan that winter shows “The War Path of the Big Bellies Nation” extending westward from the mouth of the Knife River and crossing the Yellowstone at the mouth of O’Fallon Creek (Coal Creek, or Oak-tar-pon-er). It is impossible to say whether this was supposed to be identical with the route shown on Sheheke’s map, because Clark drew both from Indian information before he explored the ground personally.

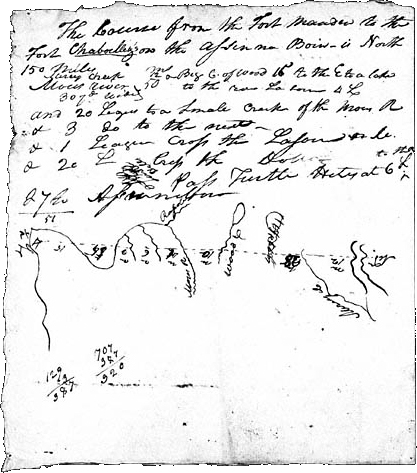

Fort Assiniboine

The Route to ‘Fort Chaboillez’s on the Assinna Boin’

To see labels, point to the map.

Courtesy Missouri Historical Society

This map contains reminders and a sketch made by Lewis and Clark during their conversations with François Larocque and other traders from the North West Company’s trading post, Fort Assiniboine, at the mouth of the Souris (Mouse) River.[3]See Larocque at Fort Mandan. It is difficult to make sense of some of the details, partly because several figures refer to miles, and others to leagues (3.0 statute miles, or 4.8 kilometers).

Ater arriving at the Mandan villages, Pryor would still need to take the majority of his horses northward to Hugh Heney at Fort Assiniboine some 200 miles to the north. The manager, or bourgeois, at Fort Assiniboine was Charles Chaboillez, to whom Lewis and Clark sent a cautiously cordial letter via free trader Hugh McCracken on 31 October 1804. They informed Chaboillez that they were sent by the U.S. government “for the purpose of exploring the river Missouri, and the western parts of the continent of North America, with a view to the promotion of general science.” Lewis assured him of President Jefferson’s open border, free trade policy:

We shall, at all times, extend our protection as well to British subjects as American citizens, who may visit the Indians of our neighbourhood, provided they are well-disposed; this we are disposed to do, as well from the pleasure we feel in becoming serviceable to good men, as from a conviction that it is consonant with the liberal policy of our government, not only to admit within her territory the free egress and regress of all citizens and subjects of foreign powers with which she is in amity, but also to extend to them her protection, while within limits of her jurisdiction.[4]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents,1783–1854 (2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd ed., 1978), 1:213–14. The phrase … Continue reading

Chaboillez replied in due time, expressing “a great anxiety to Serve us,” Clark noted, “in any thing in his power.” The Canadian’s letter was delivered on 16 December 1804 (in 6 days—express mail, considering the severity of winter on the High Plains) by Hugh Heney, or Hené. We don’t know what the factor wrote, but we do know that the courier-trader made a hit with the captains, who, according to Larocque, “Enquired a great deal of Mr. Heney, Concerning the sioux Nation, & Local Circumstances of that Country & lower part of the Missouri, of which they took notes.”[5]W. Raymond Wood and Thomas D. Thiessen, Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 143. In fact, the illustration above may be the record of that conversation.

Lewis and Clark’s “Miry Creek” was a translation of Bourbeuse—”Miry”—by which Larocque knew it. In June 1805, Larocque recorded his own experience in fording it: “We unloaded our horses and crossed the property on our shoulders there being not more than 2 feet [of] water, but we sunk up to our middle in mud, the horses bemired themselves in crossing and it was with difficulty we got them over the banks being bogs as also the bed of the river.”[6]Ibid., p. 164. Later called Snake Creek, its lower 17 became part of Lake Sakakawea when Garrison Dam was completed in 1956.

Turtle Mountain, with its summit only 500 feet (ca. 152 meters) above the surrounding plain, is nonetheless the most conspicuous landmark in the vicinity. It is the centerpiece of the 3,118-acre (1,257 hectare) International Peace Garden, which straddles the 49th parallel, two thirds of it in Manitoba, the rest in North Dakota. It is not a mountain in the “Rocky” sense, but a heavily wooded mass of glacial drift. The area is dotted with many small lakes.[7]See Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest (reprint, 1956, 3 vols.; New York: Harper, 1897), 1:308n.

Pryor’s ETA

Via the shorter route, had all gone well and Pryor had averaged thirty miles per day, he would have arrived at the Knife River villages by about August 6. The distance from there to Fort Assiniboine had been estimated by Clark at 150 miles, although actually it would have been a little over 200 miles, so it would have taken him another thirteen or fourteen days to make that round trip, not counting time to conduct his business with Hugh Heney. It is unlikely he could have gotten back to the Knife River before 20 August 1806, even under the most agreeable of circumstances. Clark, in his 12 July 1806 letter to Heney, had figured he would arrive there “about the beginning of September 1806, perhaps earlyer,”[8]Jackson, Letters, 1:312. but he actually got there on August 14, so he would have had to wait a week or more for Pryor to get back.

Drifting along with the Yellowstone’s current—Pryor’s party couldn’t have endured the dizzying Indian mode of paddling bull boats, “around and arround”—which Clark estimated flowed at 2.5 to 2.75 miles per hour, they spent at least twelve hours a day on the water, and caught up with the main party on 8 August 1806 approximately 70 miles below the mouth of the Yellowstone, near Tobacco Creek in North Dakota.

Notes

| ↑1 | Moulton’s Atlas map 116, shows “Sargent Pryors route with the Horses” as a short dotted line which, as he points out, roughly parallels the route of today’s Interstate 90. However, the modern superhighway turns abruptly southward some 20 miles east of where Clark’s map leaves off, and heads toward Gillette, Wyoming. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moulton, ed., Atlas, map 31b. |

| ↑3 | See Larocque at Fort Mandan. |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents,1783–1854 (2 vols., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2nd ed., 1978), 1:213–14. The phrase “serviceable to good men” may suggest that Lewis was consciously practicing the precepts of Freemasonry (see Lewis as Master Mason), an affiliation that is evidenced a number of times in his expedition journals. Back in Virginia, Lewis had risen quickly from Fellowcraft to Past Master Mason within the first four months of 1797. By October 1799, he was a Royal Arch Mason, which represented the completion of the Master Mason’s degree. |

| ↑5 | W. Raymond Wood and Thomas D. Thiessen, Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738–1818 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985), 143. |

| ↑6 | Ibid., p. 164. |

| ↑7 | See Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest (reprint, 1956, 3 vols.; New York: Harper, 1897), 1:308n. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, Letters, 1:312. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.