Army Regulations

American military officers of the 18th century purchased their own swords and chose whatever they fancied and could afford. The first U.S. Regulations regarding Infantry officers’ swords were published in 1787 calling for iron or steel mounted sabers 36 inches in overall length. In 1800, all commissioned officers were to change to yellow mounted swords. This regulation was changed in 1801, and infantry officers were again instructed to carry white mounted swords with blades 32″ long for officers who would be mounted, and swords with 28″ blades for officers on foot.

Judging from swords with known provenance in museums, these regulations were widely ignored. It is probably impossible at this date to know exactly which type of sword Lewis or Clark would have carried.[1]Both captains also carried dirks, which were dagger knives used by navy midshipmen. Lewis had requisitioned one for himself, but left home without it. He secured some long knives from stores at the … Continue reading

Lewis’s Sword

Lewis was known to be particular about his uniform. His duty before undertaking the leadership of the expedition was as an aide to President Jefferson, so it is likely that Lewis would have had a better quality sword.

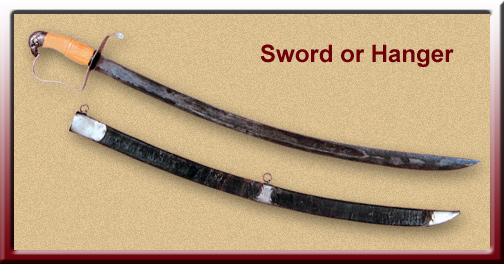

The specimen shown here is a silver-mounted sword with an ivory handle. The silversmith was a man named Campbell, of Baltimore, Maryland, who worked there about 1800. The silver hilt complies with the regulations of 1801 specifying a “white” mounting. This sword is 34″ overall length with a 29″ blade. A “sword-knot,” or string of leather, connected the sword with the wrist, in case the swordsman lost his grasp of the weapon in practice, or had it knocked from his grasp in a fight.

Although Clark received a commission as 2nd Lieutenant of Artillery, it is unlikely he carried a sword of the style meant for artillery officers. He did not find out about this commission until a few days before departure up the Missouri on the barge.

Clark’s Sword

Clark had been an infantry officer in 1791, serving with General Anthony Wayne in the frontier campaigns. At that time he would have been expected to carry an iron mounted sword. When he agreed to accompany Lewis across the country, he could have brought along his sword from his earlier service, he could have purchased a new sword, or he could have borrowed a sword from his brother, George Rogers Clark. We have no way of knowing which.

Uses on the Expedition

Rigorous training in swordsmanship was required of every officer, and every cavalryman.[2]Rules and Regulations for the Sword Exercise of the Cavalry (London: Printed for the War Office, 1796), Plate 1; p. 9. The basic offensive and defensive principles to be learned were speed, fluidity and accuracy in executing the six basic cuts and eight guards, using only motions of the wrist, never of the elbow, plus the point thrust.

As survival tools, swords were not particularly important on the expedition. At the critical point in the standoff between the Corps of Discovery and the Lakota Sioux at Bad ‘humered’ Island on 25 September 1804, one of the chiefs grew so belligerent that Clark felt compelled to draw his sword, accompanying his gesture with an order for all hands to prepare to defend themselves. Lewis followed suit.

The captains frequently saw swords in the possession of Indians along the Columbia, which had been passed up the river from the Euro-Americans traders who anchored in the estuary. On their return from the coast in March-April of 1806 they even tried to barter their swords for horses, but failed several times before Clark proffered his to the grateful Walla Walla chief Yelleppit (18 April 1806), in appreciation for the latter’s gift of a “very elegant white horse.” Lewis disposed of his in a similar way. In the final tabulations of expedition expenses, Lewis asked the government to reimburse him for his “hanger,”[3]From the late 15th century until the early decades of the 19th, swords were commonly referred to as “hangers,” or “hangars,” from the fact that the sheath was hung from a belt. which he had traded to the Indians.

Notes

| ↑1 | Both captains also carried dirks, which were dagger knives used by navy midshipmen. Lewis had requisitioned one for himself, but left home without it. He secured some long knives from stores at the Harpers Ferry armory, which at least he and Clark carried on the expedition, and ultimately used for trading. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rules and Regulations for the Sword Exercise of the Cavalry (London: Printed for the War Office, 1796), Plate 1; p. 9. |

| ↑3 | From the late 15th century until the early decades of the 19th, swords were commonly referred to as “hangers,” or “hangars,” from the fact that the sheath was hung from a belt. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.