These thermometers from Thomas Jefferson‘s collection confirm his interest in recording weather data. Thomas Jefferson Foundation records indicate the wall thermometer on the left was made by Jones & Son/Holbern in London, and obtained by Jefferson in 1789. It is 19 inches tall by 2 ¼ inches wide. No information is available on Jefferson’s pocket thermometer.

President Jefferson’s instructions to Captain Meriwether Lewis regarding his journey to explore the Missouri River and its course with the waters of the Pacific Ocean included a series of “objects worthy of notice,” among these was “climate as characterised by the thermometer . . . “[2]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, second edition, 1978 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 1:63. It was a directive of much personal interest to the president.

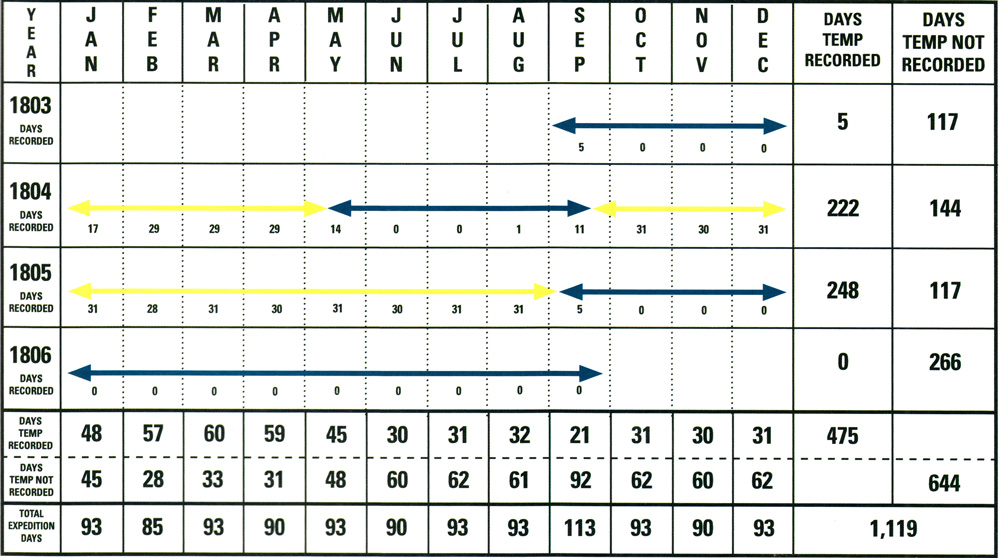

The Corps of Discovery’s mission called for daily thermometer readings. As it turned out, readings were taken on just 475 days of the journey, or 42 percent of the time. Thermometers appear and disappear throughout the captains’ journal entries, resulting in a subsequent body of literature that is filled with assumptions, probabilities, skepticism and guesswork about them.

Jefferson’s Thermometric Interest

Thomas Jefferson held a long-term interest in climate and thermometers. It is likely that he was disappointed in the incomplete temperature records.[3]Terrence R. Nathan detailed the Corps of Discovery’s climatologic records of the expedition in the November 2005 issue of WPO. He characterized Jefferson as “arguably the most … Continue reading The instructions he gave Lewis were to satisfy just one element of his ongoing interest in and passion for documenting temperatures and weather data. Jefferson had indulged this interest for more than a quarter century before Lewis embarked on his journey to the West. Historian James Rodger Fleming noted, for example, that in 1778, Jefferson and the Reverend James Madison, president of the College of William and Mary, were “making the first simultaneous meteorological measurements” in North America at Monticello and Williamsburg.[4]James Rodger Fleming, Meteorology in America, 1800–1870 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 9. Reverend James Madison was a second cousin of James Madison, the fourth president of … Continue reading

A sampling from Jefferson’s correspondence demonstrates the depth of his interest in thermometers and climate data.

8 June 1778 Jefferson wrote Giovanni Fabbroni in Italy, suggesting an exchange of thermometric data between the two countries. He indicated this would provide “a comparative view of the two climates.” Jefferson added, “I make my daily observations as early as possible in the morning & again about 4 o’clock in the afternoon . . . “[5]Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 2:194–197.

8 November 1783 Jefferson wrote Isaac Zane in Frederick County, Virginia: “By Colo. Bland who is returning to Virginia in a carriage I send you a thermometer, the only one to be had in Philadelphia. It appears to be a good one.” Jefferson asked Zane to make specific temperature observations in a cave, an icehouse, a good spring and a well, and transport the data to him in Philadelphia.[6]Boyd, 6:347.

20 February 1784 Jefferson wrote James Madison, later the fourth president of the United States: “I wish you had a thermometer. Mr. Madison of the college and myself are keeping observations for a comparison of climate . . . . If you could observe at the same time it would shew [sic] the difference between going North and Northwest on this continent. “[7]Boyd, 2:545.

2 January 1789 William Jones of London sent Jefferson two thermometers Jefferson had ordered while he was in Paris on 10 December 1788. Jones noted that they had “Farenheit’s graduation on the right of the one side of the tube and Reamur’s [sic] on the other.” They were “to be hung on the outside of a glass window . . . to be seen without opening the window.” Jones advised that the instruments could easily be placed “by fixing 2 perpendicular pieces of wood to the side of your window, and the Thermometer placed against them.”[8]Boyd, 14:411.

11 March 1797 Jefferson corresponded with Thomas Mann Randolph, his son-in-law who lived nearby, to tell him he had ordered him a thermometer from Joseph Gatty, a Philadelphia glassblower who specialized in weather instruments. Jefferson paid $12 in June 1797 for two thermometers, one for Randolph and one for himself.[9]Barbara B. Oberg, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 29:316n.

15 January 1800 Jefferson, in Philadelphia, wrote Jonathan Williams to thank him for sending a copy of Williams’s published book on thermometrical navigation the previous year. In his letter of thanks, Jefferson noted that for some time he had wished he could take a daily temperature reading in the river near his home. “Observations made in the rivers of different states would exhibit one of the good comparative views of climate . . . “[10]Oberg, 31: 308.

Jefferson’s thermometric interests during these early years of the republic were more than a personal scientific hobby. With his colleagues at the American Philosophical Society, he “had a vision of a national meteorological system.”[11]Williams was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1787 as a result of his observations on temperature and barometrical readings. Viewed in this perspective, the instructions he gave Lewis are but one component of a national project. Lewis was thus a “point man ” in a climatologic scheme of far-reaching proportions.

The Philadelphia Story

Lewis left Washington 15 March 1803, for Philadelphia to broaden his scientific skills. He stopped first in Harpers Ferry, Virginia. There he chose arms, ammunition and other accoutrements for the upcoming expedition. While there, he also supervised the design and testing of prototype sections of a lightweight collapsible, iron-framed boat, which he and Jefferson dreamed up the previous year. That endeavor prolonged his stay at the national armory by three weeks and he did not arrive in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia, until about 20 April 1803. He explained the cause of his delay to Jefferson on that date.

During an intensely busy month of study and procurement in Philadelphia, he finalized his needs and accounted in detail for his expenditure of public funds. The list of needs included “Three Thermometers.”[12]Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:69. Observers have commented that three breakable thermometers would hardly suffice for the duration of such an arduous journey.[13]Eldon G. Chuinard, Only One Man Died: The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1979), 204.

Historians including Donald Jackson and Gary Moulton conjecture that Lewis obtained at least some thermometers in Philadelphia. Atmospheric science professor Terrence Nathan, however, acknowledges that such instruments “do not appear on any list of items purchased in Philadelphia or elsewhere.”[14]Nathan, 18, n8. Lewis’s handling of public funds, as reported in the records available to us through Jackson’s references and other sources, is meticulous. An absence of accounting would be highly surprising and prompts uncertainty about where and when Lewis acquired thermometers.

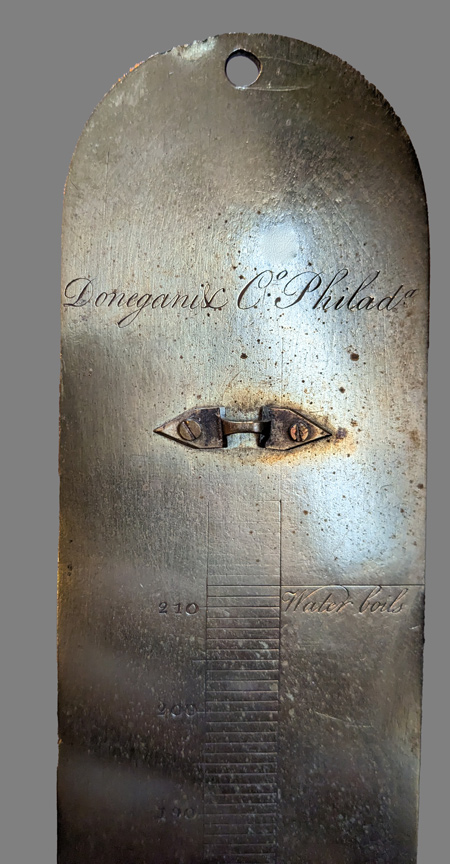

There were at least four establishments that offered glass thermometers when Lewis was in Philadelphia, according to Silvio Bedini, a historian specializing in early American instruments. His list includes one owned by Joseph Gatty, with whom Jefferson was familiar, and another by John Donegan,[15]Silvio A. Bedini, Early American Scientific Instruments and Their Makers (Washington, D.C.: Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, 1964), U.S. National Museum Bulletin 231, 33, … Continue reading a name identified with the thermometer that Clark experimented with 3 January 1804, at Camp River Dubois.[16]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:145. Clark’s reference to the Donegan thermometer is evidence that the instrument came from Philadelphia, but it does not establish that Lewis, personally with public funds, made any such purchase.”[17]“John Donegan (or Denegan) and Joseph Donegany (Donegani) were making thermometers in Philadelphia in 1785.” Moulton, 2:146–147n1.

If not in Philadelphia, then where else would Lewis have obtained the thermometer(s) used on the Ohio River 1 September 1803, and at Camp River Dubois 3 January 1804? Lewis departed Philadelphia for Washington in mid-June 1803 for his final instructions from Jefferson. At this juncture, Jefferson personally could have provided, not at public expense, the undocumented thermometer(s). Jefferson was astute at acquiring Philadelphia instruments. Jackson noted that Jefferson ordered two thermometers for himself specially packaged, “best on exposure to the weather,” about a year after his final conference with Lewis.[18]Jackson, 1:75, n1. These instruments may have been replacements for thermometers previously entrusted to Lewis. If this were the case, it is not surprising, considering political opposition to Jefferson’s project, that no mention of it appears in any record.

Thermometer Readings

In Pursuit of the Sioux

© Michael Haynes, https://www.mhaynesart.com. Used with permission.

Members of the Corps of Discovery suffered frostbite, snowblindness and bitter cold at Fort Mandan as they collected meat and conducted the grinding routine of daily chores interspersed with extremely rare moments of military action. This painting depicts a scene early on the morning of 16 February 1805, following an earlier encounter between corps members and more than 100 Sioux. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark made time every day to record the temperature and collect weather data during their time at Fort Mandan despite a variety of distractions and activity.

There is a conspicuous absence of thermometric data for the period from 7 September 1803, to 3 January 1804, at Camp River Dubois. Lewis had dutifully commenced recording temperatures promptly upon leaving Pittsburgh. He reported readings on 2 September 1803—”Thermometer stood at seventy six in the cabbin the temperature of the water in the river when emersed about the same—”[19]Moulton, 2:69. Lewis’s entry for 2 September 1803.—and the 3rd, 4th, 6th and 7th of September. Thereafter, no readings appear, with the single exception of 16 September 1803, until Clark’s record on 3 January 1804. Thus, over a four-month period, including a break in Lewis’s writing between 18 September 1803 and 11 November 1803, there is no record of any thermometer use. Considering Jefferson’s personal interest and precise instructions, this is curious to say the least.

Once settled at Camp River Dubois, the captains did take temperature readings, though somewhat sporadically during the first month when only 17 were recorded. Thereafter, daily readings occur with only a few omissions, until the corps proceeded up the Missouri River on 14 May 1804, when readings ceased, with one exception, until 19 September 1804.

Historian Doane Robinson apparently thought that no thermometer was available during those four months. He asserted that a corps member discovered a misplaced thermometer when the crew unloaded the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) to dry and rearrange their baggage that had been drenched following days of heavy rain in mid-September 1804.[20]Doane Robinson, “Lewis and Clark in South Dakota,” South Dakota Historical Collections 9, (1918), 557.

Donald Jackson declared that he found no support for Robinson’s statement that “the explorers discovered 14 September 1804 a thermometer which had been lost since the start of the voyage, a loss which had prevented their taking temperature readings until then. “[21]Jackson, 1:75n1.

Clark, however, had supervised, prior to the voyage up the Missouri River, a thorough packing of all goods and equipment on the barge. It is not surprising that some items would be securely tucked away and not found until months later. Note particularly that daily temperature recordings resumed 19 September 1804, after Clark shifted stored items following the storm.[22]Moulton, 3:130–131; also 132n1.

Moulton also disputes the Robinson inference, noting that a thermometer was available during the record-keeping hiatus from 14 May to 19 September 1804, as a single reading was taken during that period on 25 August 1804.[23]Moulton, 3:9 and 13n12.

| Year | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Days Recorded | Days not Recorded |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1803 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 117 | ||||||||

| 1804 | 17 | 29 | 29 | 29 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 222 | 144 |

| 1805 | 31 | 28 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 31 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 248 | 117 |

| 1806 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 266 | |||

| Days Recorded | 48 | 57 | 60 | 59 | 45 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 21 | 31 | 30 | 31 | 475 | |

| Days not Recorded | 45 | 28 | 33 | 31 | 48 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 92 | 63 | 60 | 62 | 644 | |

| Total Days | 93 | 85 | 93 | 90 | 93 | 90 | 93 | 93 | 113 | 93 | 90 | 93 | 1119 | |

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Of Thermometers and Temperatures on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”, We Proceeded On, November 2007, Volume 33, No. 4, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol33no4.pdf#page=17. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, second edition, 1978 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1968), 1:63. |

| ↑3 | Terrence R. Nathan detailed the Corps of Discovery’s climatologic records of the expedition in the November 2005 issue of WPO. He characterized Jefferson as “arguably the most knowledgeable meteorologist of his day” in a discussion about the information he wanted Lewis and Clark to record. Nathan wrote that the result was a significant part of “Lewis and Clark’s Meteorological Legacy.” Terrence R. Nathan, “O! How Horriable is the Day,” We Proceeded On (November 2005), 10 and 17. For a careful review of the scientific value of Lewis and Clark’s data, the reader should refer to Nathan’s article. For another summary, refer to Susan Solomon and John S. Daniel, “Lewis and Clark: Pioneering Meteorological Observers in the American West,” Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, Vol. 85, Issue 9 (September 2004), 1273. |

| ↑4 | James Rodger Fleming, Meteorology in America, 1800–1870 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990), 9. Reverend James Madison was a second cousin of James Madison, the fourth president of the United States. He served as a professor at the College of William and Mary, and later as college president, from 1777 until his death in 1812. |

| ↑5 | Julian P. Boyd, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 2:194–197. |

| ↑6 | Boyd, 6:347. |

| ↑7 | Boyd, 2:545. |

| ↑8 | Boyd, 14:411. |

| ↑9 | Barbara B. Oberg, ed., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001), 29:316n. |

| ↑10 | Oberg, 31: 308. |

| ↑11 | Williams was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1787 as a result of his observations on temperature and barometrical readings. |

| ↑12 | Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:69. |

| ↑13 | Eldon G. Chuinard, Only One Man Died: The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Washington: Ye Galleon Press, 1979), 204. |

| ↑14 | Nathan, 18, n8. |

| ↑15 | Silvio A. Bedini, Early American Scientific Instruments and Their Makers (Washington, D.C.: Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, 1964), U.S. National Museum Bulletin 231, 33, 156, 164 and 166. |

| ↑16 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:145. |

| ↑17 | “John Donegan (or Denegan) and Joseph Donegany (Donegani) were making thermometers in Philadelphia in 1785.” Moulton, 2:146–147n1. |

| ↑18 | Jackson, 1:75, n1. |

| ↑19 | Moulton, 2:69. Lewis’s entry for 2 September 1803. |

| ↑20 | Doane Robinson, “Lewis and Clark in South Dakota,” South Dakota Historical Collections 9, (1918), 557. |

| ↑21 | Jackson, 1:75n1. |

| ↑22 | Moulton, 3:130–131; also 132n1. |

| ↑23 | Moulton, 3:9 and 13n12. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.