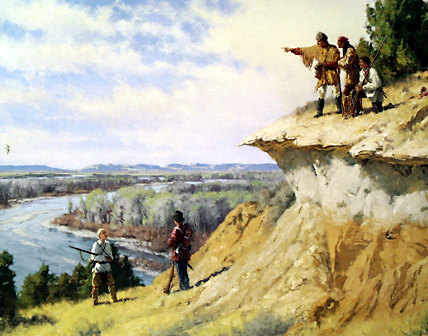

. . . one of the handsomest plains I ever beheld

Captain Lewis Sighting the Yellowstone

Oil on canvas. © 1999 by Charles Fritz. All rights reserved.

Six hundred and seventy miles of free-flowing river, the Yellowstone or Roche Jaune (row-sh zjohne), as early French explorers named it, stretches from its headwaters in the high country at the southern boundary of Yellowstone National Park to its confluence with the mighty Missouri, on the Montana-North Dakota border.

A Delightful Land

When Captain Lewis arrived at the mouth of the great river in late April 1805, he saw a “rich, delightful land, broken into valleys and meadows, and well supplied with wood and water. . . . ” He noted vast herds of buffalo, deer, elk, and antelope, and remarked on the stands of cottonwood trees in that vicinity, together with dense undergrowth of elm, ash, box-elder, willow, and wild rose.

Meriwether Lewis, Thursday, 25 April 1805:

I ascended the hills from whence I had a most pleasing view of the country, particularly of the wide and fertile vallies formed by the missouri and the yellowstone rivers, which occasionally unmasked by the wood on their borders, disclose their meanderings for many miles in their passage through these delightfull tracts of country . . . .

After leaving Fort Mandan the Corps of Discovery had passed through a “game sink” where animals were comparatively scarce, and now were entering a huge buffer zone between competing Indian tribes, a zone that historian Dan Flores has called “the American Serengeti.” From the middle of April, when they passed the mouth of the Little Knife River (they called it “Goat Pen Creek”) until the first week in June at the mouth of the Marias River, they were pacing off the width of a region overflowing with wild mega-fauna that would dwindle to near extinction before the end of the 19th century.

Indian Knowledge

This abundant environment had been home to Native Americans for millennia, and as Adrian Heidenreich has written, its resources had always “provided more than sustenance.”[1]C. Adrian Heidenreich, “The Native Americans’ Yellowstone,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 35 (Autumn 1985), 2–17. Arapooish, Chief of the Absalooka (Crow) Indians who had moved to the area about 1750, once said of their homeland, “The Great Spirit put it in exactly the right place. . . . It has snowy mountains and sunny plains, all kinds of climates and good things for every season.”

Clark had already learned much about the Yellowstone in conversations with the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians during the winter of 1804–05 at Fort Mandan. Big White, chief of the lower Mandan village, told him the Mandans called this river Meé,-ah’-zah Wakpa—Elk River.[2]“Big White Chief of the Lower Mandan Village, Dined with us, and gave me a scetch of the Countrey as far as the high mountains,…he Says that the river Roche Jaune recves 6 Small rivers on the … Continue reading Since he didn’t meet any of the Apsáalooke face to face during the expedition, he never learned their name for the Yellowstone, Lichii’likaashaashe (roughly pronounced ee-JEE-lee-gah-sha ah-zha), which similarly means Elk River.[3]In May 1806 the captains would learn the Nez Perce Indian name for the river—Wah-wo-ko ye-o-cose, as Lewis spelled it; wewúkiye kú•s, as the Nez Perce word sounds—which means “elk … Continue reading

Clark’s 1806 Confirmation

Fifteen months later Captain Clark would confirm that the Indians were about right. Most of the Yellowstone, at least as much as he saw of it, is navigable by boats about the size of the expedition’s pirogues. But it would take him two days to march from the Three Forks of the Missouri to the Yellowstone River at today’s Livingston, Montana. It’s 57 miles via modern Interstate 90, which parallels most of the Indian roads he followed. As to the navigability of the Yellowstone, it depends upon what the Hidatsas understood by “navigable,” since they generally used boats—small “bull boats” consisting of willow frames covered with bison hide—mainly to cross rivers, not to go up or down.

Reference

Paul S. Martin and Christine R. Szuter, “War Zones and Game Sinks in Lewis and Clark’s West,” Conservation Biology, Vol. 13 No. 1 (February 1999), 36-45.

The Yellowstone River Confluence is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The public can visit the Missouri-Yellowstone Confluence Interpretive Center.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | C. Adrian Heidenreich, “The Native Americans’ Yellowstone,” Montana The Magazine of Western History 35 (Autumn 1985), 2–17. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Big White Chief of the Lower Mandan Village, Dined with us, and gave me a scetch of the Countrey as far as the high mountains,…he Says that the river Roche Jaune recves 6 Small rivers on the S. Side, & that the Countrey is verry hilley and the greater part Covered with timber, Great numbers of beaver &c.” Clark, 7 January 1805. |

| ↑3 | In May 1806 the captains would learn the Nez Perce Indian name for the river—Wah-wo-ko ye-o-cose, as Lewis spelled it; wewúkiye kú•s, as the Nez Perce word sounds—which means “elk water.” Gary E. Moulton, ed. The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (13 vols, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), 7:343n. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.