Walnut Street Prison

Walnut Street Prison

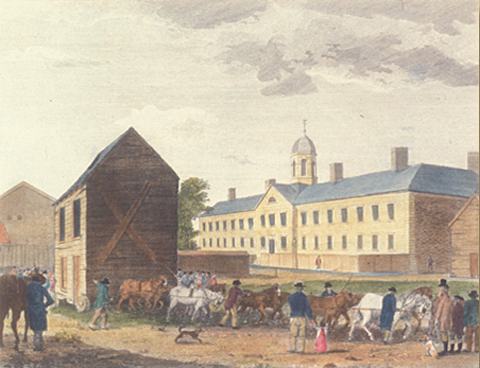

“Gaol in Walnut Street”

William Birch

Courtesy Independence National Historical Park, Karie Diethorn, Chief Curator, and with the kind assistance of library technician Andrea Ashby Leraris.[1]The prints in the INHP collection, which originated in various portfolio sets that preceded Birch’s book, The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America, as it appeared in … Continue reading

Lewis could have found the prison in a relatively bright period. Before reform of Pennsylvania’s penal laws in 1790 prisons had been holding pens; before that, punishment had consisted of public humiliation, disfigurement or execution. The prison at Walnut Street had workshops in a separate two-story building where the product of prisoners’ labor repaid their keep, and even—after certain deductions—provided something for themselves. Recidivism declined significantly. On the other hand, no such orderly prospect faced debtors thoughtfully separated from felons but given indefinite sentences waiting for something to turn up. Also apart from the rest were those whose offenses were considered severe enough to isolate them from the good and bad effects of human company for a period of penitence in solitary confinement, a form of imprisonment with psychological consequences more severe than the devisers of the system could have anticipated.

The Walnut Prison Yard was the take-off point for another adventurer/exlorer who carried instructions and question from Benjamin Rush and Caspar Wistar. On 9 January 1793, the hydrogen balloon of the French aeronaut Jean Pierre Blanchard rose from behind the prison wall temporarily enclosing a ticketed and distinguished audience, certainly including George Washington, and probably Jefferson and other officers of the federal government. (See Blanchard’s Balloon) Rush asked for pulse rate comparisons between ground and a mile aloft. Wistar required six samples of air at the same altitude, taken by emptying fluid and quickly stoppering the bottles. Washington provided a letter asking that the astronaut, who did not speak English, be treated with civility wherever he came down.

African Methodist Episcopal Church

In the 1760s Philadelphians owned nearly 1,500 slaves; by 1790 that number was less than 300, and by 1820 there were only seven slaves in the city and its suburbs. When Lewis was there in 1803, free African-Americans numbered perhaps as much as 10 percent of the city’s population of over 70,000.[2]Gary Nash, First City (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 41-42; Russell F. Weigley, ed., Philadelphia: A Three-Hundred-Year History (New York: Norton), 254.

In 1794 a 34-year-old preacher named Richard Allen, a former slave who by age 20 had earned enough money from part-time jobs to purchase his own freedom, bought the tattered wooden structure pictured above from a blacksmith, and moved it to the corner of Sixth and Lombard Streets where it was to become the birthplace of the Mother Bethel (“the house of the Lord”) African Methodist Episcopal Church. The irony inherent in the juxtaposition of the incipient A.M.E. Church’s prime sanctuary as a symbol of fellowship and hope, with the Walnut Street Gaol (then pronounced, and now also spelled, jail) as a place of isolation and despair, would not have been lost on any Black person or white abolitionist.

In 1803, the first of Bishop Allen’s education projects, a day school for black children, was operating in the church, and he had joined with Absalom Jones and James Forten in forwarding to Congress a petition to revoke the Fugitive Slave Act and abolish slavery.[3]The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 requiring the return of an escaped slave from whatever state or territory he or she had taken refuge, requiring only proof of ownership. Loosely enforced or actively … Continue reading[4]The story of the Reverend Allen’s leadership in the abolitionist movement that centered on Philadelphia during the time before, during and after the years of the Lewis and Clark expedition is … Continue reading

The A.M.E. church at large, still with the anvil as the icon of its origins and principles, now numbers more than 2.5 million members.

Washington (Southeast) Square

The Walnut Street Prison was in the block adjacent to what is now called Washington Square. Washington Square, originally called Southeast Square, was one of five such plots included in William Penn’s 1682 design for the city of Philadelphia. Twenty-five years later it became a potter’s field. It served as a pasture briefly until 1776, when casualties of Washington’s army, as well as some British prisoners of war, were buried there in long, deep pits where coffins were stacked one atop another. In 1793, victims of the fearsome yellow fever epidemic were added to the field’s host of corpses. The square was subsequently closed to burials, but it and the surrounding neighborhood when Lewis saw them before and after the Expedition were dismal and disreputable. The scene was refreshed in 1815 with the planting of some 60 varieties of trees sheltering meanders of public walkways. In 1825 it was renamed in honor of the great American general and first President.

Thereafter it suffered intermittent periods of comparative neglect until the middle of the twentieth century, when the Washington Square Planning Committee set about erecting a Revolutionary War memorial there. It was to contain the remains of an unknown Continental soldier who had died of wounds or illness. In November 1956, a search for appropriate remains found one that filled most of the requirements: it was from a mass grave and was the corpse of a man in his very early twenties with a “plow wound” that could have been produced by a musket ball. But since neither uniform nor buttons were present, the archaeologists were unable to confirm that the body was that of a soldier, and if a soldier, an American.[5]John L. Cotter et al, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 205-10.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to Walnut Street Prison and A.M.E. Church:

Notes

| ↑1 | The prints in the INHP collection, which originated in various portfolio sets that preceded Birch’s book, The City of Philadelphia, in the State of Pennsylvania North America, as it appeared in the Year 1800, measure approximately 18 by 14½ inches. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gary Nash, First City (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 41-42; Russell F. Weigley, ed., Philadelphia: A Three-Hundred-Year History (New York: Norton), 254. |

| ↑3 | The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 requiring the return of an escaped slave from whatever state or territory he or she had taken refuge, requiring only proof of ownership. Loosely enforced or actively opposed in Northern States, the Act was augmented by a stronger law in 1840. |

| ↑4 | The story of the Reverend Allen’s leadership in the abolitionist movement that centered on Philadelphia during the time before, during and after the years of the Lewis and Clark expedition is told in Historic Philadelphia, at http://www.ushistory.org/tour/mother-bethel.htm. |

| ↑5 | John L. Cotter et al, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 205-10. |