On the Ohio

Left Pittsburgh this day at 11 ock with a party of 11 hands 7 of which are soldiers, a pilot and three young men on trial they having proposed to go with me throughout the voyage.”[1]Gary E. Moulton, editor, The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:65.

With those words, written on 31 August 1803, Meriwether Lewis began his first journal entry on the epic Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Ocean.

Approaching Brunot’s Island

Watercolor by Steve Ludeman

© 2023 by Steve Ludeman, www.steveludemanfineart.com. Used by permission.

Even though Lewis himself declared the mouth of the River Dubois to be the expedition’s official point of departure, the two and one-half months spent descending the Ohio River were in fact its real beginning

Often referred to as the recruitment phase of the expedition, it was that–but so much more! The Ohio was where the all-important foundation–the nucleus–of what became the Corps of Discovery was formed. On the Ohio, Lewis and Clark met to actually form their partnership in discovery. On the Ohio, the famous Nine Young Men from Kentucky were recruited and enlisted. On the Ohio, York, George Drouillard, and at least two others joined the expedition. While on the Ohio, these men began forming relationships and friendships, and a dedication to their mission and to each other that would carry them, through dangers and hardships, to the Pacific and back. Some of these men were also among the most important members of the Corps.

When Lewis finally left Pittsburgh, at least one month behind schedule, his destination was Louisville, Kentucky, where he would rendezvous with William Clark and the men Clark had recruited. Lewis knew his friend and former army commander was coming with him. On 19 June 1803, he had written Clark inviting him to join the endeavor as co-commander. Then, after making final arrangements, he left Washington City on 5 July 1803, for Pittsburgh, arriving there on 15 July 1803. And then he waited, and waited, for the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) he had expected to be almost ready for his journey to be completed because of the “unpardonable negligence and inattention of the boat-builders who . . . were a set of most incorrigible drunkards, and with whom, neither threats, intreaties nor any other mode of treatment which I could devise had any effect.”[2]Donald Jackson, editor, The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with related Documents, 2 vols., revised edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:125. One consolation during this frustrating delay was the arrival by 3 August 1803 of Clark’s letter of 18 July 1803 agreeing to “cheerfully” join Lewis as co-leader of the Expedition and “partake of the dangers, difficulties, and fatigues, as well as the . . . honors & rewards of the result of such an enterprise, should we be successful in accomplishing it.”[3]Jackson, 1:110. Lewis’s invitation to Clark to join him on the Expedition had arrived at a perfect time in Clark’s life. He had impoverished himself trying to help his brother George … Continue reading So, happily, Clark was coming, but Lewis’s expected rendezvous with his partner in discovery in Louisville was delayed later and later, from mid-August to late August to early October.[4]Jackson, 1:57, 117, 125. In letters Lewis wrote Clark dated 19 June 1803 (from Washington), 3 August 1803 (from Pittsburgh), and 28 September 1803 (from Cincinnati), he stated his expected arrival … Continue reading He finally arrived on 14 October 1803.

While Lewis waited for his military barge to be finished, he put together his temporary crew and took three young men on trial. Two of these recruits were still with him when he reached Cincinnati on 28 September. They were most likely with him when he reached Louisville and are believed to be two of the nine men[5]Jackson, 1:125. Who those recruits were are not definitely known. It is generally agreed that George Shannon was one of them. About eighteen years old, he had been attending school in Pittsburgh, and … Continue reading enlisted at the Falls of the Ohio.[6]The Falls of the Ohio was an approximately two-mile stretch of rapids through three channels. In times of high water they could be navigated without great danger or difficulty but, as the water … Continue reading Clark, meanwhile, was busy recruiting, and wrote Lewis on 24 July 1803, that he already had men of a “discription calculated to work & go thro . . . those labours & fatigues which will be necessary.” Almost a month later, on 21 August 1803, Clark specified that he had retained four recruits and promised others an answer after consulting with Lewis.[7]Jackson, 1:113, 117. Clark is believed to have had seven recruits waiting for Lewis. They were Joseph and Reubin Field, Charles Floyd, Nathaniel Hale Pryor, John Shields, William Bratton, and perhaps … Continue reading

Shallow Water

Down the Ohio

Watercolor by Steve Ludeman

© 2024 by Steve Ludeman, www.steveludemanfineart.com. Used by permission.

After leaving Pittsburgh, Lewis found progress down the Ohio to be slow. The summer had been dry and the river was lower than anyone could remember. By late summer and ys were typically low, in that era before dams and navigation pools. Lewis’s speed down the Ohio was in the hands of Mother Nature and his own determination. Writing to Clark on 3 August 1803, he stated that he would make his way downriver even if he “should not be able to make greater speed than a boat’s length pr. day.”[8]Jackson, 1:116.

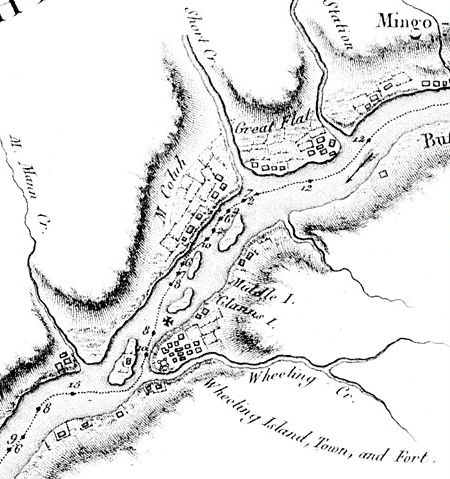

Lewis of course traveled at a faster pace than that, even if the going was sometimes painfully slow. Going past landmarks and towns that can still be visited today, Lewis and his little flotilla of barge, pirogue, and at least one canoe, made their way downstream using the current, oars, poles, and sails. But the men also had to use non-nautical means, pushing and pulling the boat by brute strength over sandbars and through sections of only a few inches deep. When the obstacles proved too difficult, Lewis hired oxen and horses from local farmers to drag the big boat downstream.[9]Moulton, 2:67-74. Within a week of leaving Pittsburgh, the boats had stopped at Brunot’s Island, where a demonstration of the air gun almost ended in disaster when a bystander was grazed by an errant ball; had passed McKee’s Rock and stopped at Steubenville, Ohio; had passed Charlestown (present Wellsburg, West Virginia) and arrived at Wheeling. Lewis noted the dense fog that formed over the river, making visibility very low. These conditions also caused such extremely heavy dews that water dripped from the trees as if it were raining.[10]Moulton, 2:67.

Lewis arrived at Wheeling on 7 September 1803. He stayed two days, allowing the crew time to rest, do their laundry, and have bread baked. He also picked up supplies he had sent overland from Pittsburgh so that the barge would be lighter in the shallow upper reaches of the Ohio, and purchased another pirogue—the red pirogue that would travel over 3,000 miles on the journey. The young explorer almost recruited a doctor, William Patterson, the son of one of his Philadelphia tutors, Robert Patterson, but the young man failed to appear at the designated departure time, apparently deciding to pass on the western adventure. On the 8th Lewis dined with Thomas Rodney, en route to Mississippi Territory to take his Jefferson-appointed position as a judge. Rodney thought Lewis “a stout young man but not so robust as to look able to fully accomplish the object of his mission.” That evening the travelers enjoyed watermelons onboard the barge.[11]Moulton, 2:74075. For Thomas Rodney’s account of his trip down the Ohio and encounters with Lewis, as well as with Clark once he reached Louisville, see the published journal of his trip … Continue reading Another tasty dish was squirrel; Lewis twice commented on the creatures migrating across the Ohio, and sending “my dog” into the river to “take as many each day as I had occation for, they wer fat and I thought them when fryed a pleasent food.”[12]Moulton, 2:79, 82. “My dog” is of course the famous Newfoundland, Seaman, who accompanied Lewis on the entire expedition. He so endeared himself to the members of the Corps that he is referred to in the journals as “our dog.” Loyal to the end, there is good evidence that Seaman was with Lewis at the time of the latter’s death in 1809 and died on his master’s grave.[13]James J. Holmberg, Seaman’s Fate.

Notes

| ↑1 | Gary E. Moulton, editor, The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:65. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Donald Jackson, editor, The Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with related Documents, 2 vols., revised edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:125. |

| ↑3 | Jackson, 1:110. Lewis’s invitation to Clark to join him on the Expedition had arrived at a perfect time in Clark’s life. He had impoverished himself trying to help his brother George Rogers Clark with his legal and financial difficulties. Only months earlier he had sold his farm Mulberry Hill outside Louisville (that he and York had called home since coming to Kentucky in 1785) and moved across the Ohio River to Clarksville to make a fresh start. |

| ↑4 | Jackson, 1:57, 117, 125. In letters Lewis wrote Clark dated 19 June 1803 (from Washington), 3 August 1803 (from Pittsburgh), and 28 September 1803 (from Cincinnati), he stated his expected arrival dates in Louisville, revising the date in each letter to reflect his current status. |

| ↑5 | Jackson, 1:125. Who those recruits were are not definitely known. It is generally agreed that George Shannon was one of them. About eighteen years old, he had been attending school in Pittsburgh, and probably joined the expedition there. The other recruit is more uncertain. John Colter is usually named as that second recruit, joining Lewis at Maysville, Kentucky, when Lewis stopped there about 24 September 1803. A more likely possibility might be George Gibson. Born in Mercer County, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, Gibson identified himself after the expedition as a Mercer County resident, therefore signifying that as his likely home when he left on the western journey. Another piece of evidence, which might be nothing more than coincidence but that must be considered, is that Gibson and Shannon both have the same enlistment date, 19 October 1803. This would have given Clark time to evaluate them and give his okay to enlisting them in the enterprise. |

| ↑6 | The Falls of the Ohio was an approximately two-mile stretch of rapids through three channels. In times of high water they could be navigated without great danger or difficulty but, as the water dropped, they could become more dangerous. The best channel was the northern one, called the Indian (later Indiana) Chute, along the Indiana shore. Louisville was founded in 1778 at the head of the Falls on the Kentucky side of the river. Clarksville was founded in 1783 at the foot of the Falls on the Indiana side. By 1803, Louisville was a major western town, growing rapidly, with a population of some 600, with thousands more in surrounding Jefferson County. Clarksville remained a small village, plagued by floods, and surpassed by Jeffersonville to its east and New Albany to its west after their founding in the early 1800s. |

| ↑7 | Jackson, 1:113, 117. Clark is believed to have had seven recruits waiting for Lewis. They were Joseph and Reubin Field, Charles Floyd, Nathaniel Hale Pryor, John Shields, William Bratton, and perhaps John Colter. Colter would be one of the recruits if Gibson was indeed already with Lewis. Three of the four that Clark mentioned as already recruited are known: the Field brothers and Floyd. Their enlistment date of 1 August 1803 is two and one-half months before Lewis arrived at the Falls and inspected potential Corps members. Who the fourth was can only be speculated. Colter, who has an enlistment date of 15 October 1803, the first after the Field brothers and Floyd, are good candidates. Nathaniel Pryor was enlisted on 20 October 1803; he was Floyd’s first cousin, and both cousins were appointed sergeants in the Corps. That two of the three Corps’ sergeants came from the Nine Young Men testifies to the quality of man that Clark recruited. Perhaps the fourth of Clark’s recruits was John Shields. Although Shields was married, Clark made an exception to Lewis’s instruction to recruit unmarried men, knowing that Shields’ skills as a blacksmith, gunsmith, and hunter would be of crucial importance. His enlistment date was 19 October 1803. Or was the fourth William Bratton? He might have been one of those likely young men who applied to Clark, perhaps venturing eastward from Woodford County, Kentucky, or northward from south central Kentucky upon hearing about the Expedition. His enlistment date was 20 October 1803. A final possibility is Clark’s enslaved African-American, York, but it is unlikely that Clark would have counted his servant as one of the recruits. In some ways, he was a nonperson, someone to be there to take care of the needs of his master, but not worthy of notice, and certainly not in an official capacity as an expedition recruit. York would go on the entire journey, becoming the first African-American to cross the United States from coast to coast, but never be carried on the rolls as an official member nor be compensated. Any reward for his loyal and important service would have to come from his master. It is not known if Clark rewarded him. It is also possible that none of these men was the mysterious fourth recruit, because that man did not go on the Expedition. See also Nine Young Men from Kentucky. |

| ↑8 | Jackson, 1:116. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, 2:67-74. |

| ↑10 | Moulton, 2:67. |

| ↑11 | Moulton, 2:74075. For Thomas Rodney’s account of his trip down the Ohio and encounters with Lewis, as well as with Clark once he reached Louisville, see the published journal of his trip entitled A Journey through the West, edited by Dwight L. Smith and Ray Swick (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997). Also of interest are Rodney’s letters written to his son on the journey published in 1919 in The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (vol. 43). |

| ↑12 | Moulton, 2:79, 82. |

| ↑13 | James J. Holmberg, Seaman’s Fate. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.