Lewis and Clark were fortunate in the pair of individuals they met at the mouth of the Grand River in the first days of October 1804, Arikara Too Né (Eagle Feather) and Joseph Gravelines. The resident trader and interpreter Gravelines proved to be so reliable and so good at the immediate tasks put to him that long after the Lewis and Clark Expedition he was employed by the United States government to represent its interests among the Arikara.[2]David Lavender, The Way to the Western Sea: Lewis and Clark Across the Continent, (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 145: “Joseph Gravelines turned out to be a marvelous acquisition.” Lewis, who was not one to exaggerate the merits of others, called him “an honest discrete man and an excellent boat-man.”[3]Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 4:7. After the winter of 1804-05, when Corporal Richard Warfington undertook the return of the expedition’s military barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) to St. Louis, with its precious cargo of reports, letters, maps, artifacts, and live animal specimens, the captains designated Gravelines as the pilot of the voyage.

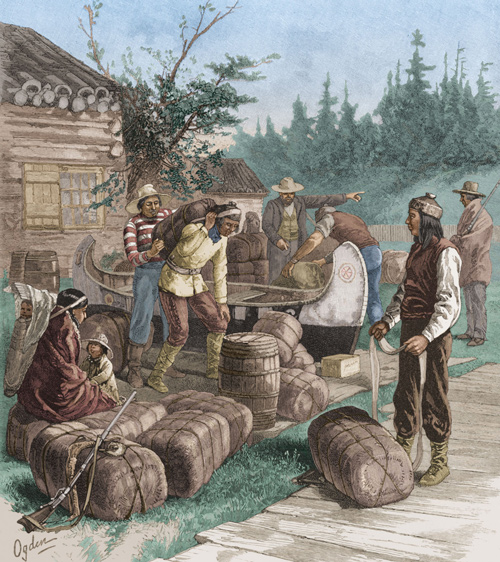

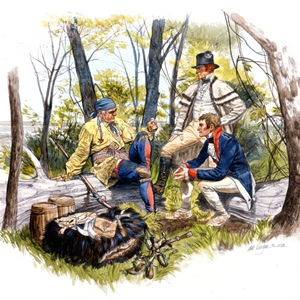

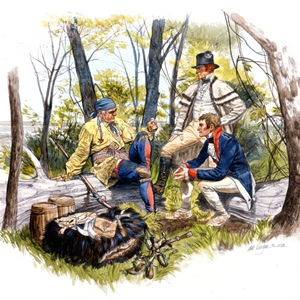

Because they were explorers and not professional linguists, Lewis and Clark depended on the ad hoc translation services of such white traders and trappers as they met on their journey to the Pacific Ocean. With the Yankton Sioux they were fortunate to have the assistance of Pierre Dorion, Sr., who had lived among them for almost twenty years. Unfortunately, Dorion was no longer with the Corps of Discovery when they had their troubled encounter with the Teton [Lakota] Sioux near today’s Pierre, South Dakota. Some of the mutual confusions of that tense four-day encounter might have been avoided had Dorion served as cultural liaison. Among the Mandan Lewis and Clark employed René Jusseaume. Even though Clark characterized him as “a Cunin artfull an insoncear”[4]Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 3:203. fellow, Jusseaume was their only significant intermediary with the Mandan. In fact, he and his family accompanied the Mandan leader Sheheke and his wife and child to Washington, DC, in the aftermath of the expedition. The expedition’s Hidatsa interpreter was the colorful Toussaint Charbonneau, who apparently had only the most rudimentary knowledge of Hidatsa. Nor did he speak much English.

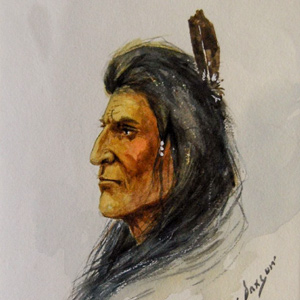

The expedition’s interpreter among the Arikara was a French trader named Joseph Gravelines. Joseph Gravelines was an associate of traders Pierre-Antoine Tabeau and Régis Loisel. Gravelines first appeared in the journals on 8 October 1804 as the expedition reached the Arikara villages near the mouth of the Grand River just south of today’s North Dakota-South Dakota border. Clark calls him “(Mr. Gravotine a French man [who] joined us as an interpreter).”[5]Moulton, Journals, 3:151. Gravelines accompanied the expedition on its journey from the Arikara to the Mandan villages. He translated the Arikara Too Né’s running commentary on the region through which they traveled. Once the expedition reached the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, Gravelines played a critical role in the diplomatic exchange between the Arikara diplomat Too Né, the Mandan people, and the expedition leadership.

Shuttle Diplomacy, 1804–05

Gravelines was a busy man in the fall and winter of 1804-05. He was engaged in an early version of what today is called “shuttle diplomacy.” He made several trips between the Arikara and the Mandan villages, and he served as courier for letters exchanged between Lewis and Clark and Pierre-Antoine Tabeau.

As the ice began to break up on the Missouri River in the spring of 1805, Toussaint Charbonneau became demanding and obstreperous, setting conditions for his employment that the captains found intolerable. At that point Lewis and Clark seriously considered firing Charbonneau and proceeding west of the Mandan villages with Gravelines as their general interpreter. Had this occurred, it is certain that Sacagawea would not have accompanied the expedition. Charbonneau eventually capitulated. At the time of the Charbonneau crisis, Sacagawea had not yet been named in the expedition’s journals. Had the contract negotiations broken down, the first or second most famous Native American woman in American history would almost certainly have died nameless and unnoticed by history’s record keepers.

Too Né’s Delegation

Joseph Gravelines accompanied Too Né to Washington, DC, in December 1805, and remained with the Arikara leader until his death in April 1806. At some point between April 1805 and February 1806, Gravelines assisted Too Né in fashioning his map of the Arikara world. At the very least, Gravelines provided French captions for the places and events Too Né memorialized on his map. After Too Né’s death, President Jefferson sent Gravelines back to the Arikara villages with his letter of condolence, approximately $300 of gifts, and the unenviable responsibility of explaining Too Né’s death to the tribe.[6]See also on this site Too Né, Eagle Feather and Too Né’s Delegation.

As the Lewis and Clark Expedition made its way down river to St. Louis in the autumn of 1806, they encountered a trading party on 12 September 1806, near today’s St. Joseph, Missouri. A man named Robert McClellan was the leader of the party. On board were Pierre Dorion, Sr., and Gravelines, who was traveling upriver to fulfill President Jefferson’s condolence mission. It was then that Gravelines confirmed Too Né’s death, a rumor of which the captains had heard several weeks earlier when they encountered three Frenchmen at the Arikara villages.[7]Moulton, Journals, 8:311.

On 12 September, Clark wrote, “we examined the instructions of those interpreters and found that Gravelin was ordered to the Ricaras with a Speech from the president of the U. States to that nation and some presents which had been given the Ricara Cheif who had visited the U. States and unfortunately died at the City of Washington, he was instructed to teach the Ricaras agriculture. . . .”[8]Moulton, Journals, 8:357.

The irony of Jefferson’s suggestion that Gravelines teach farming practices to the Arikara, who had been masters of agriculture and grain storage for centuries before Columbus bumped into America, was probably lost in the more somber message he was carrying on the president’s behalf.

Gravelines overwintered somewhere in the middle reaches of the Missouri River (perhaps near the mouth of the Platte River), and did not reach the Grand River villages until early June 1807. With the help of a trader named Charles Courtin he delivered the bad news of Too Né’s death. Apparently the Arikara succumbed to the timeworn habit of blaming the messenger.

Later Years

Gravelines survived the crisis and managed to regain the trust and respect of the Arikara people. Gary Moulton notes that Gravelines was reported in 1811 as having lived among the Arikara for more than 20 years, often, in the post-expedition era, as an official agent of the United States government.[9]Moulton, Journals, 3:154n8.

Related Pages

October 8, 1804

Arikara village Sawa-haini

Near present Mobridge, South Dakota, Pvt. Frazer is promoted to the permanent party and assigned to Sgt. Gass. Camp is near Sawa-haini—an Arikara village where the interpreter Joseph Gravelines is found.

November 5, 1804

Raising the huts

The day is spent raising Fort Mandan cabins and splitting boards for the cabin lofts. Mandan hunters report capturing 100 pronghorns, Clark’s rheumatism continues, and Lewis spends the day writing.

November 6, 1804

Northern lights

During the night, the guard wakes the captains so they can view the Aurora Borealis. Joseph Gravelines and four St. Charles boatmen leave for the Arikara villages to promote Mandan-Arikara peace.

December 2, 1804

A Cheyenne delegation

When four Cheyennes arrive at Fort Mandan, the captains give them a speech, tobacco, a flag, and demonstrations of many ‘curiosities’. They also give them a letter of warning for the Sioux and Arikaras.

February 16, 1805

Scorched earth

Many miles south of Fort Mandan and the Knife River Villages, Lewis and his soldiers continue their pursuit of a Sioux war party. They come to an old Mandan village where two lodges have been set afire.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Traders arrive at the Knife River Villages with news and two plant specimens for Lewis. About six miles from Fort Mandan, several enlisted men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

March 14, 1805

Charbonneau moves out

Interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau terminates his employment and moves out of Fort Mandan with the intent to return to his Hidatsa village. The enlisted men are tasked with shelling corn.

April 6, 1805

A diplomatic delay

Some visiting Mandans tell the captains that the entire Arikara nation has moved to one of their old villages nearby. The captains postpone leaving Fort Mandan to learn more.

April 7, 1805

Leaving Fort Mandan

The permanent party leaves Fort Mandan bound for the Pacific Ocean. They make it only as far as Mitutanka, one of the Knife River Villages. In the barge, the return party heads towards St. Louis.

September 12, 1806

Given up for dead

At present St. Joseph, Missouri, the captains modify orders given to Pierre Dorion and Joseph Gravelines. An old military companion, Robert McClellan, says that they have all been given up for dead.

Notes

| ↑1 | Clay S. Jenkinson, “Joseph Gravelines”, We Proceeded On, May 2018, Volume 44, No. 2, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is provided at http://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol44no2.pdf#page=21. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | David Lavender, The Way to the Western Sea: Lewis and Clark Across the Continent, (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 145: “Joseph Gravelines turned out to be a marvelous acquisition.” |

| ↑3 | Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 4:7. |

| ↑4 | Gary Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 3:203. |

| ↑5 | Moulton, Journals, 3:151. |

| ↑6 | See also on this site Too Né, Eagle Feather and Too Né’s Delegation. |

| ↑7 | Moulton, Journals, 8:311. |

| ↑8 | Moulton, Journals, 8:357. |

| ↑9 | Moulton, Journals, 3:154n8. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.