Nearly all the “discoveries” of the Lewis and Clark Expedition were already found by those living there and would be found again by Euro-Americans soon after. Their ethnographic data, on the other hand, provides us with a snapshot in time that can never be replicated. Historian James P. Ronda explains:

The ethnographic legacy has proven to be one of Lewis and Clark’s most durable contributions…. Guided by Jefferson’s precise instructions and their own curiosity, expedition ethnographers amassed a virtual library of information about the Indians. Journal entries, vocabularies, drawings, maps, artifacts, population estimates—all hold priceless knowledge about Indian ways from the great river to the western sea. In their writing, drawing, and collecting they managed to capture an essential part of American life on the edge of profound change.[1]James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), 254.

Beginning with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, the U.S. government set the vast area north of the Missouri (approximately 20 million acres) aside as the “Blackfeet Hunting Ground” for the Blackfeet and other tribes—Cree, Assiniboine, Gros Ventre, and Sioux.

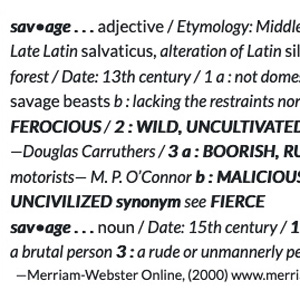

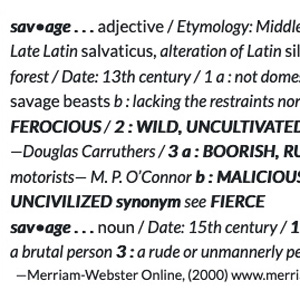

The word has two faces, one benign, the other brutish. The first springs from its etymological history, and represents the face of pure innocence. On the darker side, it is closer to the Latin cognate, saevus, meaning brutal, cruel, barbarous, violent and severe.

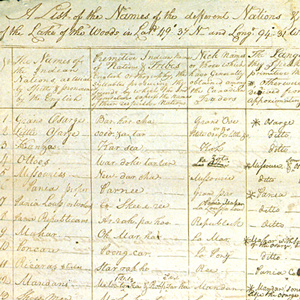

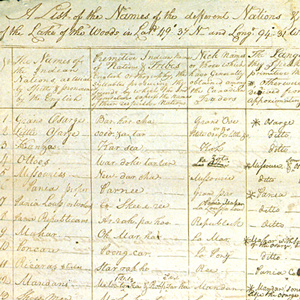

The expedition had one major outcome that was made available to the public well before the expedition was over, the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” which Lewis and Clark sent back on the barge in April 1805.

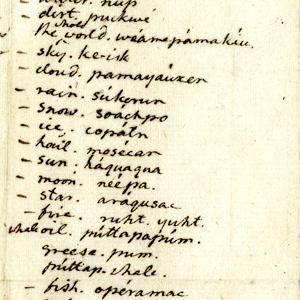

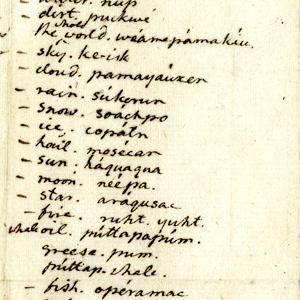

The Indian Vocabularies

by Bob Saindon

Due to the many unfortunate events which followed Lewis’s death, in 1809, the Indian vocabularies the captains had carefully collected are now lost, and were never made available to the public.

Indigenous Agriculture

Archaeological evidence indicates that deliberate burning of forests and fields has been occurring on the North American continent for at least the past 10,000 to 20,000 years. In 1603, Samuel de Champlain took Jerusalem Artichokes found in Indian gardens back to France where it soon became a staple food there. The cultivation and storage of important food plants had long been practiced before Euro-Americans came to teach the Native Americans about agriculture.

Indian Horses in the PNW

by Barbara Fifer

One of the reasons Clark had so much difficulty in purchasing horses at The Dalles in the spring of 1806 is that he was at the very northwestern edge of their dispersal across North America.

Indian Maps

by John Logan Allen

The native peoples encountered by Lewis and Clark differed from non-Indians in their manner of linking space and time, distance and direction. The reasons were primarily the result of the contrasting needs of the hunter-gatherer and subsistence farmer versus those of the commercial farmer, townsman, or tradesman.

The comments made by Ordway and Gass about Frazer selling his razor for two Spanish dollars can tell us much about the ethno-history of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and the native peoples of the Plateau.

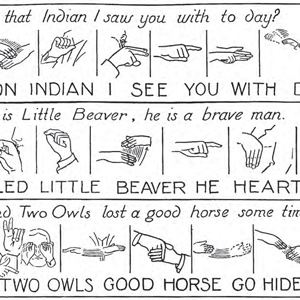

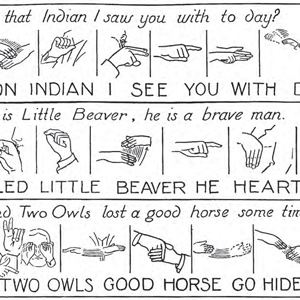

“our guide could not speake the language of these people but soon engaged them in conversation by signs or jesticulation, the common language of all the Aborigines of North America.” Lewis exaggerated the universality of sign language, which was mainly employed by tribes of the Great Plains.

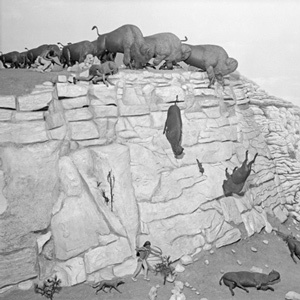

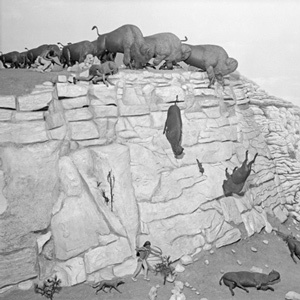

Early American Hunting

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Governor William Bradford of the Massachusetts Bay Colony hired the local Indians to hunt for the colony. Early Americans later learned several hunting methods from Indians such as relaying, driving, and still hunting.

The Lewis and Clark’s bear claw necklace, recently ‘rediscovered’, is described and analyzed and suggests some of the many meanings and provocations related to it.

Indian Gifts

Almost one-third of the $2,160 Lewis spent on purchases by Israel Whelan went for Indian presents, not only to supply some of the Indians’ anticipated wants but also to showcase some of the more attractive goods they might learn to want.

Both of the captains referred to Charbonneau’s young wife as a squaw, usually spelling it with a post-vocalic /r/—”Squar.” In the 1980s a nationwide movement arose to extirpate squaw from general use, because of its worst connotations.

Next to grizzly bears and Mother Nature, the most feared enemy of American fur trappers traveling along the upper Missouri River were the Niitsítapi or Blackfeet, the “Original People” or “Prairie People.” Was that Lewis’s fault?

Bostonian George Ticknor catalogued the “strange furniture” of the four walls of the room after his visit in 1815, listing heads and horns, “curiosities which Lewis and Clark found on their wild and perilous expedition,” mastodon bones, and the two Native American painted hides.

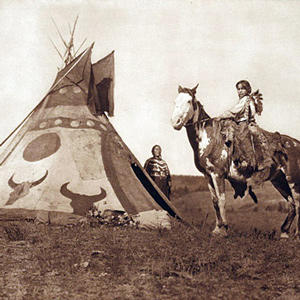

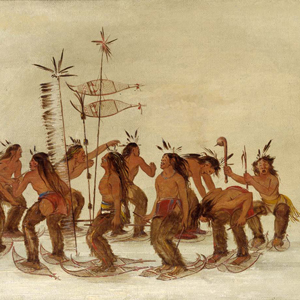

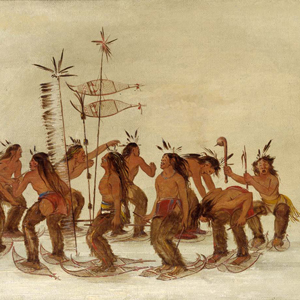

Lewis and Clark as Ethnographers

by James P. Ronda

As ethnographers, the captains provided “names of the nations & their numbers” and recorded the strange cultures they encountered. Their work as ethnographers is examined here by James Ronda.

Rush’s Questions for Indians

Vices, morals, and religion

Benjamin Rush provided Lewis this list of questions about Indian medicine, vices, and religion.

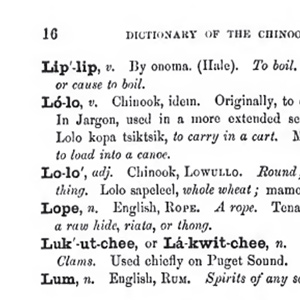

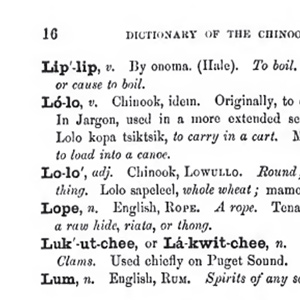

Lewis and Clark appear to have been unaware of the existence of Chinook Trade Jargon. Never-the-less, some of the words they encountered would be later documented as part of the jargon.

Notes

| ↑1 | James P. Ronda, Lewis and Clark among the Indians, Bison Book ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), 254. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.