Helping the Expedition

The Clackamas people had about twelve villages south of the Columbia River, along the Clackamas River, and at Willamette Falls in what is now Portland and Oregon City. They spoke the Clackamas dialect as did nearby Multnomahs and Skilloots.

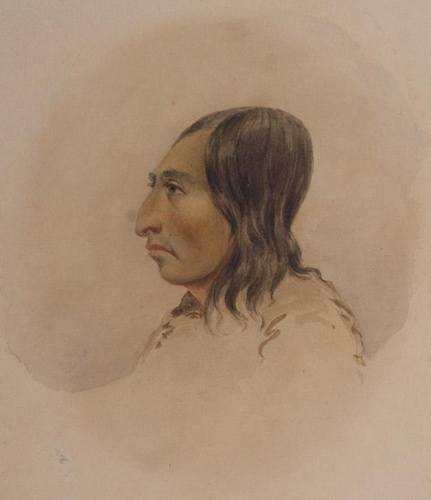

Indian Head in Profile (1847)

Paul Kane (1810–1871)

Watercolor and pencil on paper, 5 7/8 x 4 9/16 inches (14.9 x 11.6 cm). Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, collections.starkculturalvenues.org/objects/40629/indian-head-in-profile?ctx=6eeed7f3-5ae5-49a5-b886-30da440364bf&idx=209.

On 2 April 1806, two young Clackamas men came to “Provision Camp” near present-day Washougal and sketched a map of the Willamette River, the mouth of which the expedition captains had failed to find. At the time, Willamette, pronounced wlámt or wəlámt, was the name of a Clackamas village. The captains called the river the Multnomah, and they hoped it was the speculative river connecting California with the Columbia.[1]William Bright, Native American Placenames of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 567. Spelled Cash-hooks, Cush-hooks, Clark a’mos Nation, and Clark a-mus nation in the journals, the people’s name comes from gitláq̀imaš meaning ‘those of the Clackamas River’.[2]Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 544.

The Clackamas shared Willamette Falls with their southern allies, the Kalapuyas and people from the Watlala village below Beacon Rock.In the Estimate of the Western Indians, Clark recorded the “Clark-a-mus” population at 1800.[3]Moulton, Journals, 6:486.

Paul Kane’s Observations

In January 1847, the artist Paul Kane left Fort Vancouver for Oregon City. There, he painted the city and its Clackamas inhabitants. Of them he wrote:

About four miles below Oregon the Klackamuss enters the Walhamette; and, seated on the banks at its mouth, I saw a party of Indians of the Klackamuss tribe, and I put ashore for the purpose of taking a sketch of them. They were busy gambling at one of their favourite games. Two were seated together on skins, and immediately opposite to them sat two others, several trinkets and ornaments being placed between them, for which they played. The game consists in one of them having his hands covered with a small round mat resting on the ground. He has four small sticks in his hands, which he disposes under the mat in certain positions, requiring the opposite party to guess how he has placed them. If he guesses right, the mat is handed round to the next, and a stick is stuck up as a counter in his favour. If wrong, a stick is stuck up on the opposite side as a mark against him. This, like almost all the Indian games, was accompanied with singing; but in this case the singing was peculiarly sweet and wild, possessing a harmony I never heard before or since amongst Indians.

This tribe was once very numerous; but owing to their close vicinity to Oregon City, and the ease with which they can procure spirits, they have dwindled down to six or eight lodges.[4]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 196–97.

“Oregon City” (1847)

Paul Kane

Oil on paper, 8 3/16 x 13 3/8 inches (20.8 x 34 cm). Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, collections.starkculturalvenues.org/objects/46353/oregon-city?ctx=7d740a7a-db95-4efd-8039-0535c900e9ac&idx=2.

Paul Kane also recorded the industrial development of the Willamette Falls area:

Oregon City contains about ninety-four houses, and two or three hundred inhabitants. There are a Methodist and a Roman Catholic church, two hotels, two grist mills, three saw mills, four stores, two watchmakers, one gunsmith, one lawyer, and doctors ad libitum. The city stands near the Falls of the Walhamette which is here about thirty-two feet high.

The water privileges are of the most powerful and convenient description. Dr. M’Laughlin, formerly a chief factor in the Hudson’s Bay Company, first obtained a location of the place, and now owns the principal mills.[5]Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 191–92.

The Treaty Years

In 1851, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon Territory, Anson Dart, negotiated a treaty. The treaty was never ratified frustrating many tribes who expected agreements to be executed upon acceptance rather than having to wait up to two years for ratification from unseen parties. At the time, there were twenty mills operating in Clackamas lands, and another attempt to treat was made. The treaty of 1855 was signed and ratified that same year. Eighty-eight Clackamas people represented by the Palmer treaty in 1856 were moved to the Grand Ronde Agency which became a permanent reservation the next year.[6]David G. Lewis, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 321–22; Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A … Continue reading The diverse tribes at the Grand Ronde often spoke the common Chinuk Wawa pigeon language, and a dictionary was written based on the contributions from elders living there.[7]The Chinuk Wawa Dictionary Project, Chinuk Wawa: As Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It (Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, 2012).

Lewis and Clark Encounters

April 2, 1806

Exploring the Willamette River

Clark sets out to find the Multnomah River and at its mouth, resorts to trickery to entice Indians to trade for food. At Provision Camp, Lewis says the berries are all gone except for the Oregon grape.

April 3, 1806

Mapping the Willamette River

Clark concludes his exploration of the Willamette River and learns that a smallpox epidemic had devastated the local population. At Provision Camp, Lewis demonstrates the air gun as a defensive measure.

Notes

| ↑1 | William Bright, Native American Placenames of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004), 567. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Michael Silverstein, Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast Vol. 7, ed. Wayne Suttles (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1990), 544. |

| ↑3 | Moulton, Journals, 6:486. |

| ↑4 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 196–97. |

| ↑5 | Paul Kane, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America . . . . (London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859), 191–92. |

| ↑6 | David G. Lewis, Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, ed. Robert T. Boyd, et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013), 321–22; Robert H. Ruby, John A. Brown, and Cary C. Collins, A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2010), 34. |

| ↑7 | The Chinuk Wawa Dictionary Project, Chinuk Wawa: As Our Elders Teach Us to Speak It (Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon, 2012). |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.