That is the way the Swedish physician and naturalist Carl Linnaeus[1]Correctly spelled, Linnæus, the web-friendly, Linnaeus is used on this site. —ed. (1707-1778) summarized the overriding theme of his life and career, which he devoted to the construction of a system for organizing the apparently chaotic connections within and among the three kingdoms of nature: plants, animals, and stones. The tenth edition of his monumental Systema Naturae, published in 1758, opened with an epigraph from Psalm 103, verse 24, from the Clementine Vulgate Bible:

O JEHOVA Quam magnificata sunt opera tua!

Omnia in sapienta fecisti;

impleta est terra possessione tua.

How varied are your works, Lord!

In wisdom you have made them all;

the earth is full of your creatures.”

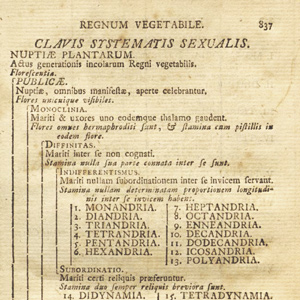

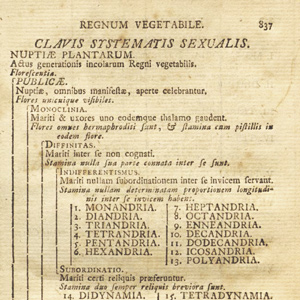

His method was simply to arrange the members of the plant kingdom into a logical order according to the observable features of their flowers, so as to reveal the orderliness inherent in Divine creation. By this means Linnaeus established a new basis for exploration and understanding in the science of botany. He organized the plant kingdom into twenty-four classes according to the reproductive features of their respective flowers, calling it his sexual system. The very idea of comparing floral reproduction with human sexuality was shocking to many, but whereas most naturalists soon began to appreciate the logic of it, for the next hundred years others found the idea repulsive, Linnaeus’s invocation of Jehovah notwithstanding.[2]In 1789 Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828) published his Reflections on the Study of Nature, based on Linnaeus’s works. He assured his readers that “one fact, which all may learn from … Continue reading With the animal kingdom the reproductive process was too obvious to require explanation.

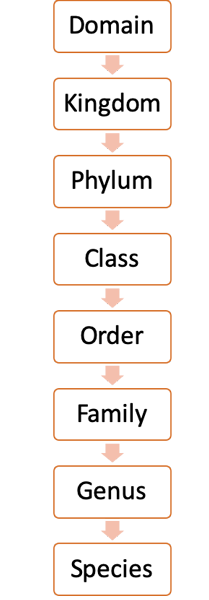

Very soon after Systema Naturæ appeared, other naturalists began to modify and expand Linnaeus’s system. Before long the rank Phylum (Division in the field of botany) was inserted between Kingdom and Class, and Family between Order and Genus. The resulting seven-layered hierarchy, which still is basic to the Linnaean system, engaged the energies of more and more naturalists in Europe and America, so that even in Lewis and Clark’s day, new species were being discovered, described, classified and pictured so rapidly throughout Europe, Asia, and North and South America, that the orderliness Linnaeus had sought to clarify was beginning to become blurred, partly because of the slow pace of travel, which protracted communication.

Enlightened Methodology

Above the materialistic motives for the Lewis and Clark expedition—to find the best route across the continent for “the great engine” of commerce (see The Fur Trade)—and beyond the continental and global strategies of geopolitics that surrounded and sometimes threatened it, much of the daily work of the two captains was inspired by a set of transcendental values grouped under the rubric of Enlightenment philosophy. Initiated by ancient Greek philosophers, refined by humanists during the Renaissance and by rationalists during the Age of Reason, the concept of the universe as a great Chain of Being was based on the premise that the universe is complete and orderly, and that the primary duty of mankind as a whole is to observe, describe, and name all the constituent elements, and discern their intrinsic connections with one another.[3]Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 59-61. Guided by the principles first propounded by Linnaeus, Lewis and Clark were active participants in the process of exploring the structure of the universe that Divine Providence had created.

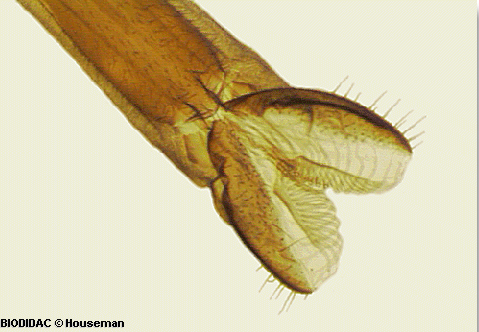

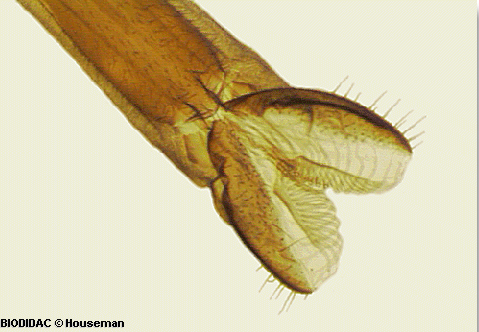

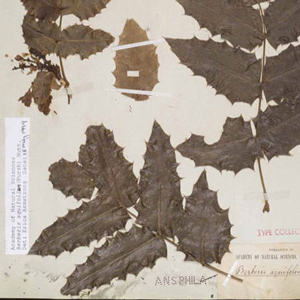

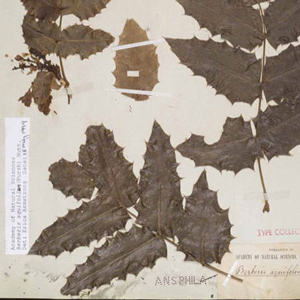

At the turn of the nineteenth century, in order for the taxonomy of a previously unrecorded animal to be universally recognized by scientists as belonging to the worldwide catalog of living creatures, a systematic record, written by a qualified naturalist, had to appear in print in a book or periodical acknowledged as a reputable source. The record had to consist of a detailed description of a representative specimen; a binomial Latin expression identifying the species it represented and the genus to which that species evidently belonged; citations of previous records of the animal; and an accurate figure (picture) of the type specimen. Priority was a crucial standard of acceptance. If two or more scientists happened to publish different taxonomies for the same species, the first publication of record was considered definitive. The basic challenge was to classify the new species in the correct Order and genus of Linnaeus’s system, which required some training in the field of comparative anatomy (see Georges Cuvier)—accounting for the fact that most naturalists in those days were educated as physicians—as well as access to museums where specimens of similar species could be studied, and to libraries where the latest research was collected.

Beyond Linnaeus

Carl Linnaeus’s original catalog eventually included some 7,700 plants and 4,400 animals, but by the close of the twentieth century, biologists estimated there were as many as one hundred million species on earth, of which only 1.75 million had been identified, and only 80,000 systematically placed in their respective trees of life. Moreover, the rediscovery in the 1920s of the conclusion by Gregor Johann Mendel (1722-1884) that biological traits are inherited according to certain natural laws, spawned the science of molecular genetics, which vastly expanded the scope of wildlife biology.[4]See, for example, Gordon Luikart and Fred W. Allendorf, “Mitochondrial-DNA Variation and Genetic-Population Structure in Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis),” … Continue reading The picture has become deeper and richer than Carl Linnaeus, and those who subsequently followed his lead, had ever imagined it could be.

Shakespeare was right. “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

Related Pages

The connections between the Linnaeus system, the Captain’s specimens and descriptions preserved and written during the Expedition, and post-expedition natural historians are evident within this site’s treatment of individual species. Notable examples include:

Potts, might have called it a grosser Mücke (large gnat) or a Stechmücke (biting gnat). Labiche and Drouillard might have called it a cousin or a moucheron. But ever since early Colonial days it has chiefly been known in America by its Spanish name, mosquito.

The nomenclatural morass associated with the scientific name of Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii, is a long and complex tale and tied closely with the early explorations along the western coast of North America . . . .

At Fort Clatsop on 5 February 1806, Reubin Field returned from a hunt with “a phesant which differed but little from those common to the Atlantic states.”

In his journal for 12 February 1806, Lewis described the plant that now goes by the name Berberis aquifolium, which he had first noticed in the vicinity of the Cascades of the Columbia River, about 145 miles from the ocean.

Bighorn Sheep Encounters

by Joseph A. Mussulman

During a reconnaissance assignment eight miles up the Yellowstone River on 26 April 1805, Joseph Field became the first member of the Corps to glimpse a live bighorn sheep.

Because it appears in the Rockies at the edges of receding snowbanks it has also earned the name glacier lily. Lewis’s specimen, collected 15 June 1806 on the Clearwater River, was the one used by Pursh to describe the species.

The science of the orderly classification of all living and extinct organisms is called taxonomy. It comprised a hierarchical outline of descriptors extending between the most general and the most specific and Lewis and Clark had a role.

Its oak-strong, hickory-tough wood made powerful, reliable hunting bows. Early French explorers and traders translated its Indian name into bois d’arc,–”wood for a bow,” which was easily anglicized into “bodark.”

“The prickly pear is now in full blume,” he wrote on a mild early-summer day in 1805, “and forms one of the beauties as well as the greatest pests of the plains.”

Deer

Drouillard spotted their first mule deer on 5 September 1804, on the cliffs upstream from the mouth of the Niobrara River in northeast Nebraska. Another deer new to them was related, the Columbian black-tailed deer.

In 1758, the great Swedish classifier Carl Linnaeus urged every scientist to give join him in using a universal and simplified system of classification. He had just published a new text re-naming every plant and animal he knew with a two-word Latin label—a binomial.

Early American Entomology

by Joseph A. Mussulman

There were only four notable 18th century naturalists who showed much interest in America’s insects: a young Englishman named Mark Catesby, Finnish botanist Peter Kalm, Philadelphian William Bartram, and Reverend Frederick Melsheimer of New Hampshire.

Bighorn: Sheep or Goat?

by Joseph A. Mussulman

We confront the paradox that Elliott Coues pointed out in 1893—that Lewis and Clark had mistaken goats with wool … for sheep, and sheep without wool . . . for ibexes. Succeeding naturalists heightened the misunderstanding with invidious comparisons.

Notes

| ↑1 | Correctly spelled, Linnæus, the web-friendly, Linnaeus is used on this site. —ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In 1789 Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828) published his Reflections on the Study of Nature, based on Linnaeus’s works. He assured his readers that “one fact, which all may learn from [the Reflections, is, that the study of Nature does not necessarily tend to make a man irreligious, as some weak people have been made to believe.” The American botanist Almira Lincoln (1793-1884), was less equivocal. In 1829, she published the first of ten highly successful editions of her Familiar Lectures on Botany that she delivered to pupils in numerous “female seminaries.” She avoided the unmentionable words by the use of euphemisms, such as “germ” for “ovary,” and discreet circumlocutions–many of which are still in use –to demonstrate that “the vegetable world offers a boundless field of inquiry, which may be explored with the most pure and delightful emotions. Here the Almighty seems to manifest himself to us . . . and it would seem, that accommodating the vegetable world to our capacities of observation, He had especially designed it for our investigation and amusement, a well as our sustenance and comfort.” Smith’s Reflections were published in three installments in The Columbian Magazine (Philadelphia) beginning in January 1789. Mrs. Almira H. Lincoln, Familiar Lectures on Botany, Practical, Elementary, and Physiological, with a [descriptions of] The Plants of the United States, and Cultivated Exotics, &c. (New York: Huntington and Savage, 1945), p. 15. |

| ↑3 | Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964), 59-61. |

| ↑4 | See, for example, Gordon Luikart and Fred W. Allendorf, “Mitochondrial-DNA Variation and Genetic-Population Structure in Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep (Ovis canadensis canadensis),” Journal of Mammalogy, Vol. 77, No. 1 (February 1996), 109-123. [For a discussion of present animal and plant populations see worldanimalfoundation.org/advocate/how-many-animals-are-in-the-world/—KT, ed.] |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.