On 11 September 1805, the expedition leaves Travelers’ Rest and follows a trail high above Lolo Creek in Montana. After passing some hot springs, they follow a trail to the Bitterroot divide at Packer Meadows.

They briefly follow the Lochsa River, but due to its steep canyons, they must climb to the ridges high above. It then commences snowing and there is virtually no game to be had. At one point, Clark writes “I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life”.

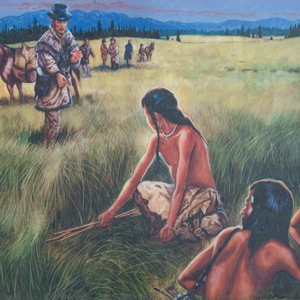

The travelers subsist on portable soup, tallow melted from candles, and their own precious horses. Clark and a small party scout ahead eventually reaching two Nez Perce villages at Weippe Prairie. They are welcomed and given food, much of which is sent back to Lewis with the main party.

The expedition moves down to the Clearwater River where a camp is established to build canoes. Unfortunately, most of the men are too sick to help.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Flathead Salish

The first whites to encounter the Salish in person were the Lewis and Clark Expedition at Ross’ Hole. Although the journalists had much to say about the encounter, the Salish have said far more.

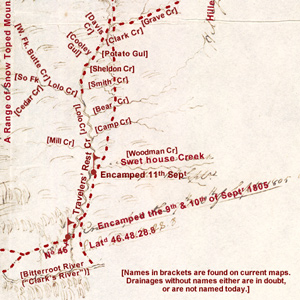

Mapping the Lolo Trail

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Clark did not randomly insert wiggly lines merely to hint at the topography around K’useyneiskit. By comparing his sketches with a modern USGS map we can make reasonably good guesses as to what drainages he actually saw.

The Northern Nez Perce Trail

Traces of the ancient trail

by Steve F. Russell

Imagine a time when all travel was on foot. This ancient time was the beginning of travel across the rugged Bitterroot Mountains for the Indian tribes of the northwest United States. This is a story of travel in those mountains from ancient times up to the present.

Synopsis Part 4

Lemhi Valley to Fort Clatsop

by Harry W. Fritz

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

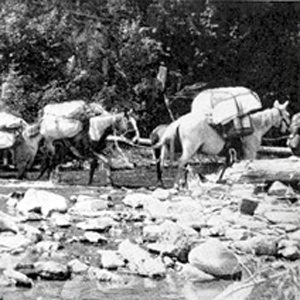

Horse Packing

Traveling with horse and mule

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Loading and handling a packhorse is hard work. It demands not only a great deal of physical strength and endurance, but also an eye for balancing a load on the first try, a head full of horse sense, the patience of a saint, and lots of experience.

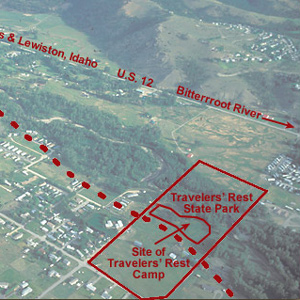

Travelers’ Rest

Hub of the west

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In the afternoon of 9 September 1805 they turned westward at a creek they dubbed Travelers’ Rest, today known as Lolo Creek. They stopped at a gathering place that Indians had been using for that same purpose for thousands of years.

Travelers’ Rest Creek

Today's Lolo Creek in Montana

by Joseph A. Mussulman

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon, 11 September 1805, Toby led the Corps of Discovery out of Travelers’ Rest camp toward the Bitterroot Mountain barrier.

Bitterroot Mountain Granite

Large outcrops of rock

by David D. Alt

The expedition camped amid very picturesque boulders of pink granite at Lolo Hot Springs, and crossed large masses of it on their way across Idaho.

Lolo Hot Springs

"beautiful to see"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“These Springs are very beautiful to See, and we think them to be as good to bathe in &c. as any other ever yet found in the United States,” avowed Private Joe Whitehouse.

Packer Meadows

"A pretty little plain"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis acknowledged it was “a pretty little plain of about 50 acres plentifully stocked with quawmash” and “one of the principal stages or encampments of the indians”

The Lochsa River

Packer Meadows to Colt Killed Creek

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Snow was falling in the high country above them on the morning of 14 September 1805 when, after striking camp two miles downstream from Packer Meadows, the Corps slogged down the Glade Creek canyon through rain and sleet.

Climbing Wendover Ridge

Leaving the Lochsa

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“Several horses Sliped and roled down Steep hills which hurt them verry much The one which Carried my desk & Small trunk Turned over & roled down a mountain for 40 yards & lodged against a tree, broke the Desk…”

Snowbank Camp to Lonesome Cove

Tough going

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Although none of the journalists mentioned it, the very presence of last winter’s snow on those mountains in late September must have aroused the feeling that crossing the Rockies was going to be even tougher than they had figured.

The Bitterroots by Air

"Tremendious Mountanes"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life,” Clark complained. “Indeed I was at one time fearfull my feet would freeze in the thin mockersons which I wore.”

A ‘Sinque’ Hole

Below the Smoking Place

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Private Whitehouse reported: “Camped at a Small branch on the mountain near a round deep Sinque hole full of water.”

Hungery Creek

And a return to Bald Mountain

by Joseph A. Mussulman

By the evening of 17 September 1805, their seventh sleep west of Travelers’ Rest, it was obvious to the captains that the Indians’ assurance that they could cross the mountains in six days was false, whereas the prediction that they would find no game there was all too true.

Weippe Prairie Villages

Nez Perce camas grounds

by Joseph A. Mussulman

For countless generations, Weippe Prairie (prounouced WEE-yipe), like Travelers’ Rest, was a major node in the transportation, trade, and social networks of the Rocky Mountain West.

Eldorado Creek

Full Stomachs to Pheasant Camp

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“we killed a few Pheasants, and I killd a prarie woolf [coyote] which together with the ballance of our horse beef and some crawfish which we obtained in the creek enabled us to make one more hearty meal.

Rocky Point Views

One last view

They crossed over the peak without pausing for one last view of “those tremendious mountanes . . . in passing of which,” Clark would assert two days later, “we have experienced Cold and hunger of which I shall ever remember.”

Today’s Bitterroot Mountains

Lewis stated that “the discoveries we have made will not long remain unimproved.” Today’s Bitterroots appear ‘unviolated’ yet much has changed.

Wheeler’s Lolo Crossing

On the Northern Nez Perce Trail

by Barbara Fifer, Joseph A. Mussulman

One of Wheeler’s most successful efforts to amplify any part of Lewis and Clark’s route was his exploration of the Lolo Trail. For that he relied heavily on Elliott Coues’ 1893 annotations to the expedition’s narrative.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.