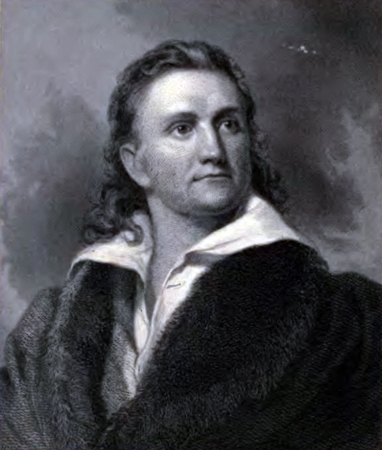

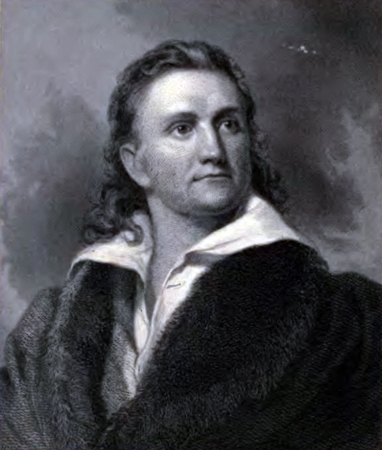

There is ample evidence that John James Audubon drew inspiration from Lewis and Clark’s writings. Between 1839 and 1852, already famous for his beautiful paintings in The Birds of America (4 vols., 1827–38), John James Audubon (1785–1851), aided by his sons John Woodhouse and Victor, and the naturalist John Bachman, published the 3-volume Quadrupeds of North America. It included 150 plates lithographed by the talented William Hitchcock and hand-colored by J. T. Bowen under the artists’ supervision.

Featured Works

After the night of 3 June 1804, just past the Moreau River in present-day Kansas, Clark and Ordway reported that a loud bird sang all night. They called it a nightingale, but no such species lives in North America. Just what type of bird did they hear?

En route to the Pacific Ocean, Lewis and Clark saw both species of eagles that are native to North America: the black-and-white one called the bald eagle, and the brown-and-gold one commonly known as the golden eagle, but which the explorers knew as the grey eagle.

Drouillard spotted the first “Deer with black tales” on 5 September 1804, on the cliffs upstream from the mouth of the Niobrara River in northeast Nebraska. By 10 May 1805 Lewis had seen enough specimens to write an 800-word description of the new species.

Lewis got his first close look at that “large hare of America,” when one of the Corps’ ace hunters, Private John Shields, bagged the first specimen more than 1,100 miles (by Clark’s estimate) up the Missouri River.

America’s greatest ornithologist, John James Audubon, was just starting his career when Lewis and Clark returned, and there is ample evidence that he drew inspiration from Lewis and Clark’s writings.

September 13, 1803

Marietta, Ohio

At sunrise, the boats move down the Ohio River. They lift the barge over a few riffles and see a flock of passenger pigeons. Anchored opposite Marietta, Ohio, Lewis writes a letter to President Jefferson.

Lewis had no reason to write about the common or fallow deer of the East Coast, although in using it for the purpose of comparison, he gave quite a clear picture of it. John Godman’s 1828 description relied partly on Lewis and Clark’s journals.

They didn’t get credit for it, but Lewis and Clark were the first to describe these wily canine predators.

One of the most confusing terms in Lewis and Clark’s lexicon of quadrupeds was the adjective long-tailed—or longtailed. At the Three Forks on 29 July 1805, he compounded the ambiguity.

This secretive, primitive little rodent, which somewhat resembles the woodchuck and the muskrat, belongs to the same mammalian order, Rodentia, as the beaver, Castor canadensis, but otherwise they have nothing in common.

Lewis’s conviction that the “black tailed fallow deer of the coast” and the “common fallow deer” were two distinct species was sufficient to urge later investigators to try to clarify them.

The species remained nameless until John James Audubon dubbed it neglecta because, he wrote in 1840, although “the existence of this species was known to the celebrated explorers of the west, Lewis and Clark . . . no one has since taken the least notice of it.”

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.