Fort Clatsop Summary

The last time the Corps saw a grizzly bear east of the Rockies in 1805 was on the lower Jefferson River near the Three Forks of the Missouri. They saw no bears in the Lemhi, Salmon, or Bitterroot River valleys along the east side of the Bitterroot Range, nor on the Indian trail over the mountains. They noticed some bear sign in the vicinity of Celilo Falls in October 1805, and came upon some tracks in the vicinity of Fort Clatsop that winter, but made no mention of which species had made them.

Nonetheless, in February 1806 Captain Lewis felt himself ready to summarize what he had so far discovered about four-legged animals in the Northwest. He wrote:

The quadrupeds of this country from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean,” he wrote, “are first the Domestic Animals, consisting of the Horses and Dogs only; 2ndly the Native Wild Animals, consisting of the White, brown or Grizly bear (which I believe to be the same family with a merely accidental difference in point of Colour). . . .

And so on, devoting most of his remaining 800 words that day, 15 February 1806, to a discourse on Indian horses and mules.

On the next day, he wrote briefly of the Indian dog, then continued his remarks on the grizzly.

The brown, white or grizly bear are found in the rocky mountains in the timbered parts of it, or Westerly side but rarely; they are more common below the rocky Mountain on the borders of the plains where there are copses of brush and underwood near the watercou[r]ses. they are by no means as plenty on this side of the rocky mountains as on the other, nor do I beleive that they are found atall [sic] in the wody country, which borders this [Pacific] coast as far in the interior as the range of mountains [the Cascade Range] which pass the Columbia [river] between the Great Falls [Celilo Falls] and rapids [Cascades of the Columbia] of that river.

Long Camp Observations

Endangered Species Act

The Endangered Species Act (Public Law 93-205) was signed by President Richard Nixon on 28 December 1973. Its purpose was “to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved, and to provide a program for the conservation of such endangered species and threatened species.” It was amended in 1978 and 1982, mostly for purposes of clarification.

The Act defined “endangered species “as “any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range.” “Any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range “was identified as “threatened.”

The criteria for determining threatened and endangered species were originally listed as follows: (1) “the present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of its habitat or range”; (2) “overutilization for commercial, sporting, scientific, or educational purposes”; (3) “disease or predation”; (4) “the inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms”; (5) “other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.”

At present there are more than 1,400 animal and plant species on the list, including Ursus arctos horribilis, which was added to the list on 28 July 1975. More information about the ESA is available from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Recently, efforts have been under way to change—some say weaken—the Endangered Species Act.

—Joseph Mussulman

Bitteroot Background

“When famed explorers Lewis and Clark traveled through the Bitterroot Mountains of central Idaho in the early 19th century, they found a large and healthy population of grizzly bears living in the area.”

Thus begins the National Wildlife Federation’s Web site on Grizzly Bear Reintroduction in the Bitterroot Ecosystem of Idaho and Montana.

There may indeed have been “a large and healthy population” in the Bitterroot Mountains, but the explorers didn’t see them. In fact, Meriwether Lewis summarized his observations on their habitats in his journal entry for 16 Febuary 1806:

The brown, white or grizly bear are found in the rocky mountains in the timbered parts of it or Westerly side but rarely; they are more common below the rocky Mountain on the borders of the plains where there are copses of brush and underwood near the water courses.

Actually, there were at least a few grizzlies in the Bitterroots until the 1940s. Recently, a proposal to reintroduce them into that ecosystem has become a controversial issue in western Montana and eastern Idaho.

—Joseph Mussulman

It wasn’t until they got back to the west slope of the Bitterroot Range in May that Lewis had occasion to expand on those conclusions. During their month-long residence at Long Camp near the Nez Perce chief Twisted Hair‘s village on the Clearwater, while waiting for snow to melt among the peaks and ridges of the Bitterroots, bear meat became a staple in their diet, the spring chinook salmon run wasn’t due in for several more weeks. They killed at least seven grizzlies.

On 15 May 1806, after the hunters brought in two brown bears that Private John Collins had bagged, and three that Private François Labiche had killed, Lewis observed,

These bears gave me a stronger evidence of the various colored bear of this country being one species only, than any I have heretofore had. . . . In short it it is not common to find two bear here of this species presicely of the same colour, and if we were to attempt to distinguish them by their callers and to denominate each colour a distinct species we should soon find at least twenty.

By the end of the month, Lewis turned to the Indians for their knowledge and experience; they called the grizzly Ho-host, or white bear, and the black bear Yâck-kâh. “This distinction of the Indians,” said Lewis, “induced us to make further enquiry relative to their opinions of the several species of bear in this country.”

The white, the deep and pale red grizzle, the dark brown grizzle, and all those which had the extremities of the hair of a white or frosty colour without regard to the colour of the ground of the poil [or pile, the dense, fine-textured undercoat], they designated Hoh-host, and assured us that they were the same as the white bear, that they ascosiated together, were very vicisious [vicious], never climbed the trees, and had much longer nails than the others.

“The white and the grizzly of this neighbourhood are the same of those found on the upper portion of the Missouri,” Lewis concluded, but he decided that they were not as ferocious as the grizzlies of the Missouri because they fed mainly on roots rather than on live animals such as bison. “They have attacked and faught our hunters already, but not so fiercely as those of the Missouri.” Nevertheless, the hunters were ordered to go out only in pairs.

The last grizzly they saw west of the crest of the Bitterroots was in the vicinity of Weippe [pronounced WEE-eyep] Prairie in mid-June of 1806. They saw no more until Lewis reached the Great Falls of the Missouri on 15 July 1806, and Clark chased one on the Yellowstone on 16 July 1806.

Insights from Charles Jonkel

Interview transcript:

Attitudes

When I first started grizzly bear work, on the east front of the mountains, here in Montana, grizzly bears hadn’t gone out on the great plains for about fifty years. They were not tolerated. If they went out there they were killed. Those that weren’t killed learned not to go out there. It was just a layover thing from when bears, and wolves, and all those kinds of animals were bad, were bad for agriculture especially. Stockmen of various types, lumber people. They all wanted the bears dead.

And there was continent-wide sentiment, both in Canada and the U.S. to kill those kinds of animals, because they interfered with the good animals, and they interfered with agricultural interests. Of course, both countries were agriculturally based at that time and everybody thought in terms of agriculture. And this hung over clear into the mid-1900s, and in Montana the attitude was essentially still that way along the East [Rocky Mountain] Front. Bears were bad. They weren’t allowed out there.

With the Endangered Species Act [of 1973, 1978, 1982] and with the research, we started talking to people, and teaching people things about bears, and finding out things about bears, and gradually the attitude changed. Now a good lot of the people think it’s great that grizzly bears go out 30, 40 miles onto the plains from the mountains. And this has happened in about 15 years, this change in attitude.

And the bears learned it very quickly. They found out they don’t get shot when they go out there, and so they now go way out past Choteau, past Augusta [west of Great Falls, Montana], and places like that.

Survival

There were bears all over the plains, way out in the plains, but they were pretty much along the rivers. People think they were spread evenly along the plains, and that’s the way the maps show it. That they were spread out all over the plains. But they were along the rivers and the draws and the creek bottoms, and such. And they were primarily there for the berries—the prairie buffaloberry, the chokecherries, the kinnikinnick [bearberry], all those sorts of things. A lot of times there was better production out there. Or maybe in a bad year in the mountains, they were better out there, and it was an alternative for them. There were also the buffalo migrations, and the buffalo jumps, and such, and they took advantage of that as well. But I think they were primarily out there for the vegetation.

We get the idea from Lewis and Clark and other early accounts that there were just tons of grizzlies out on the great plains. But I don’t think there were. I think there were tons of them along the streams. Of course, in those days they didn’t have I-90 and I-94, and such. You travelled on the rivers. So you were literally travelling all day, and every day, right through the pantry for the bears, and of course they had a lot of encounters. Had they been on the high ground, out in the middle of the prairie, I don’t think they would have had nearly this trouble. But it was impossible. They had to stick to the water to keep track of where they were, but also for all the resources along the streams.

Another thing that bothers me about those accounts, and the status of the bears now: You’ll read in books that the grizzly bears were driven from the great plains, or they were driven from the big valleys into the mountains for their sanctuary. Well, that isn’t what happened. What happened was that the ones who lived out there were killed, and the ones that were in the mountains survived.

Right up to the worst of times for the grizzly bears, Montana kept a pretty good grizzly bear population. And it wasn’t that we loved grizzly bears more than people in other states. It’s just that our mountains are so wide—you know they’re 200 miles wide, the Rockies are, in this area—and they’re very rugged. And we tried to kill them all, and we couldn’t; we just didn’t get to it. We were well on the way in the 1950s, with the new poisons and such, to killing them all. But it was about that time that people started questioning whether that was really right that we kill them all. In effect, we ended up with grizzly bears when hardly anybody else had them, because we just weren’t capable of killing them all, which was lucky for the grizzly bears.

I think, lucky for us too, when you look back on it all.

In the Bear’s Pantry

Lewis and Clark had a different kind of experience with bears. I think you have to remember the times, and the place. They were coming all day, every day, through the bears’ pantry. They were going by buffalo jumps, they were going by log jams that had carcasses of buffalo washed into them from the spring thaw, and the bears were concentrated along those. And of course they will protect their food, just like we will protect our food, and our vehicle, our children. So, there they were, coming upriver, right up to their necks in grizzly bears. And these were bears that had dealt with native people, and I think they had their way with native people in a lot of cases. Of course, they didn’t have good weapons, and if the bear wanted to take your meat cache, or whatever, unless you were well-prepared, you were better to get out of the bear’s way—and “Welcome to my food, brother.” That sort of an approach.

Here were bears. It was their home. It was their food cache. Their young were right nearby, and the people they’d dealt with in the past were pretty much a pushover. This was the situation they were up against. Even so, I don’t think the bears were exploiting Lewis and Clark. They were defending their food; they were defending their hunting area; or whatever. Or defending the area where their young were. So day after day, that’s what they were walking into. Every day they’d walk into some other bear’s food cache, or walking into a place where some other bear had her young. I think it was to be expected that would happen.

Of course, they were going by buffalo jumps, where . . . I’m sure the bears . . . just like when we had boneyards east of the mountains, where ranchers took all the dead livestock in the spring out to the boneyard. These were a hundred years old, and bears would come from up to a hundred miles to the boneyard. They knew where the boneyard was, they knew when there was meat there. Plus, they could smell it from probably 10 miles away.

I’m sure they did the same thing with buffalo jumps; I’m sure they did the same thing with log jambs. They knew where there’d be food. And the humans . . . had to travel on the water, and the water was where all the bears were. They, of course, had an agenda. They had to move on upstream. They literally had to fight bears, at times, going upstream.

The prairie was not like that, and I’d like to re-emphasize that. That was the highway, and it was the bears’ kitchen, and storeroom, and it was inevitable they’d have a lot of trouble with grizzly bears. It doesn’t surprise me at all.

It wouldn’t be the case, now. You could still use that river. A lot of people do, and it’s very enjoyable. But I think it was a pretty scary thing when they went down through there.

Management

Management of wildlife is pretty much a North American creation, at least on the huge scale that we do it. It’s keyed back to sportsmanship. Here, we, the common people, had access to wildlife, and we wanted to keep it that way. And so we invented management, and laws, and eventually wildlife research. We couldn’t do much in terms of management with bears except kill them all, and hope you got the right one. It’s not that long ago that people did that. I remember when I first started working on bears, Glacier Park had a bear incident, and they called the damage control people, who came in and killed seven bears. They said, “Well, we think we got the right one.” The Park Service said “Thank you.” And they said, “Well, call us again if you have another problem.”

That’s the way things were done right up into the sixties. That was poor management. But we didn’t know enough about bears. You couldn’t do research on bears. We were doing a lot of management on deer, and ruffed grouse, and things. We had data-bases for management, and all that. But it was impossible, literally, to work with bears until the invention of the dart gun and the quick-acting drugs, in the late fifties. All of a sudden, then, we could build databases on bears. Also, that coincided with the changing attitudes toward bears that people started to have. People wanted data, and would fund research, and as the data came in, management improved.

Sure, they’re such an intractable animal, how are you going to manage them. Well, you do it with the habitat. You do it with road closures. You do it with teaching the public to stay away from kill areas, as there could be a bear defending it. And teaching people about bear behavior. Give them a chance. They’re trying to live with us. Just don’t kill them every time you see them. It took a while for that to soak in, but people pretty much have that attitude now. And we’ve gotten used to the fine points in terms of productivity.

Bears are tough animals to manage, because there’s a fear factor, there’s the conflict of interest, there’s people who just plain hate ’em and just want ’em dead. There’s other people who think they’re the symbol of wilderness, and want every one saved. There’s others who want a trophy on the wall, above all else. How do you meet all those demands? So it’s hard, from that standpoint.

They’re also difficult to manage because they’re a very expensive animal to manage. This is one problem Montana has had. Doing the research is very expensive, and doing the management is very expensive. We’re not a rich state. We’ve got most of the grizzly bears. And we literally can’t afford to do what needs to be done for the nation. So, with the Endangered Species listing as Threatened, that allowed federal money to come in.

And that was partly on purpose, done that way, to allow federal money to come in and help with the management and help with the research, because the state just couldn’t handle it. We couldn’t afford to manage the grizzly bears and do research that the nation needed. There has never been much talk about that, but that’s what was going on. We had to get some federal money involved, even though it comes with all sorts of baggage, we had to have the federal money involved in order to do what needs to be done for the bears. Every single thing you do costs thousands of dollars. You can’t even look at grizzly bear research without at least $100,000 a year for multiple years.

They live a long time, you know. There are bears that live in the wild over 30 years. Well, if you’re going to find out about the whole species, you’ve got to keep the study going a long time. Who’s going to pay the bills? But, with extrapolations from other bears, and other species, and the databases we have, there’s been some pretty careful management installed that takes pretty good care of the bears, I think.

Some people—Management? You’re interfering with nature. Well, it’s true, but of course we’ve interfered with nature so much for so long that we’ve got to do some things to help nature do what nature needs to do. And a lot of management is really keyed to letting nature be nature. She can kick our tail around yet, but she also needs help from people. Mother Nature doesn’t run everything any more.

Behavior

The present-day grizzly is still the grizzly. Animals evolve, but they evolve very, very slowly. There’s been no genetic change. Even what we call the plains grizzly, and the barren-ground grizzly, just grizzly bears that lived out there–genetically–behaviorally they learned things differently, and they did things differently. I think what we’ve got today is the same grizzly bear that Lewis and Clark encountered, genetically. But I think behaviorally we’ve got a somewhat different animal. They’ve learned about—the Gary Larsen cartoon—what a rifle is, and stuff like that. I think in many cases they hear engines, a truck, or a vehicle, they’ve had bad experiences, or they’ve watched other bears, or elk, or something, run when they hear an engine coming. So they move away from exposed areas. We don’t see them because they heard us coming, and that relates to a bad experience either to them or some other animal, and they move out, and we don’t see them.

So, behaviorally they’ve learned to be shyer of us than they were in Lewis and Clark’s day. I think they have probably quite a bit more respect for the two-legged bear, which is fine. That’s the way they should respond to us, and I think that’s what we require from them, that they don’t push it. That if they find a way out they back out.

Well, there’s always the occasional grizzly about that won’t do that, but I think, partly, we haven’t done the research that’s necessary in that area of behavior. I think bears are capable of altering their relationships with us even further. There are a few people out there who are doing research of that nature now, where they walk around out in the woods with wild bears. The bear gets used to them as another bear that’s not competing with them, and seem to appreciate the company. That kind of research scares me because a lot of people misinterpret it, and go out there too soon with too little information. I think people doing that research must be extremely careful. I think some day we’re going to have a much better relationship with bears, and be able to live with them more compatibly, but if people go too far too fast, without adequate information, they actually can work against that. But I see some glimmers of promise out there, that we will do that kind of research, that we will have a different relationship with bears, more like the coastal bears have with other bears. You know—”There’s salmon to be caught. Let’s not argue.” I think we’re going to go that way with bears.

There’s something about human beings—we like to do that. We did it with songbirds—we used to eat songbirds, then we gave them special status. Then we did it with things like whales. And I think we’re going to do it with things like wolves and bears, too. We’re going to give them a special status. I think we’re going that way. I’m not sure just where it will lead, but it’s very interesting. I think that that might happen.

Bears in the Bitterroots

The Selway-Bitterroot area is kind of unique and different when it comes to bears. It is bear habitat, but it’s granitic, so there are huge areas of just rock. The soils aren’t as rich as limestone soils would be. So I don’t think this is as productive, at least in some bear foods. But another thing about the Bitterroots: It used to have salmon runs on the west side, and it used to have the Bitterroot Valley on the east side of the Bitterroots. When Lewis and Clark came through I’m sure the bear used the Bitterroots, but maybe not at time of year that they were in the Bitterroots. I don’t know how many days they spent in the Bitterroots, but you’re looking at probably a couple of weeks each way. And if it was the wrong time of year you’re not going to see many bears. If you come through in the winter you wouldn’t see any.

But certainly the bears used the Bitterroots. Right up until the thirties and early forties there were grizzlies that came into Missoula, into the Rattlesnake [valley], by Rattlesnake school, and out by the meat-packing plant by Reserve, where grizzlies came down out of the Bitterroots and out of the Rattlesnake [mountains] to feed on carrion.

Another thing about the Bitterroots is that they’ve been burned terribly, by fires early in the century. So early in this century, and on into the 20s and 30s, that was sheep country. There were very few trees in the Bitterroots. It was grassland, and there were sheep all over the Bitterroots, and I think the bears did quite well. But in those days it wasn’t just sheepherder, it was a sheepherder and a kid with a rifle that was with the sheep. And the kid with the rifle shot bears and wolves and coyotes, and other vermin. So it was quite a different world then. I think, in terms of today, it still is grizzly bear habitat. It’s not as good as Glacier Park, or the Whitefish Range, or areas on up into B.C. and Alberta. But nonetheless it could have grizzly bears. They won’t have salmon to feed on, they won’t have the Bitterroot Valley to use. There will be some problems, I think, until they learn they can’t go down and eat apples in the Bitterroot Valley. But they will learn that. It takes time. It might take a generation or two. With something like augmentation or reintroduction, with wolves and bears, you’ve got to give them time. They’ve got to learn how to use an area. They’ve got to learn the do’s and the dont’s. It took several generations to eliminate them from areas; it’s going to take several generations, probably, for them to learn how to use an area again.

I think grizzlies can survive in the Bitterroots. I don’t think there’ll ever be a high density of them. But there needs to be more research. I’m quite upset with the way the whole thing has gone. There’s a whole list of research topics that weren’t dealt with that should be, such as the soil type, and the plant foods that are there, or aren’t there. That should be documented. What are the black bears going to think of grizzlies coming in? It’s plumb full of black bears right now, and if you take sub-adult grizzly bears and put them into a dense population of black bears, the big black bears are going to kill the little grizzlies. So I think we need a database on that. We need connecting corridors. We need to know what they are and where they are, and make sure the corridors are there, and protected.

So to my mind there’s a lot of research that should have been done. A lot on public attitudes for people in the Bitterroot, and for potato farmers over on the other side of the mountains. Sure they’re going to be afraid of grizzly bears. If there’s none there, and you say I’m going to bring some in, they’re going to be afraid. And you have to deal with that in terms of research and in terms of programs. That wasn’t done.

Recent Developments

Pelts of bear and lynx trapped in the Lochsa River drainage about 1915 by Bert Wendover (left) shown here with Dad McCann at Lolo Hot Springs.

Told by doctors he had but a short while to live, Wendover moved to the Lochsa River alone in 1911 and built a cabin at the mouth of the creek later named for him, where he lived for another quarter of a century. To vary the bear-meat diet he gigged salmon and steelhead as they ended their spawning runs in his creek.[1]Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the most Practicable and Economical Route for A Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Made under the direction of the Secretary … Continue reading

On 14 September 1805, the Corps of Discovery’s Lemhi Shoshone guide, Toby, had mistakenly led the party down into the valley of the Lochsa River, where, being short of provisions, they killed and ate a colt they had brought for that purpose. The following day they followed the Indian trail four miles west to the base of a ridge now called Wendover Ridge, and climbed about 3,500 feet to the main trans-montane trail.

Clark wrote:

Several horses Sliped and roled down Steep hills which hurt them verry much. The one which Carried my desk & Small trunk Turned over & roled down a mountain for 40 yards & lodged against a tree, broke the Desk. The horse escaped and appeared but little hurt. Some others verry much hurt. . . . From this mountain I could observe high rugged mountains in every direction as far as I could See. With the greatest exertion we Could only make 12 miles up this mountain and encamped . . . near a Bank of old Snow about 3 feet deep.

After Lewis and Clark, the next Bitterroot Mountain grizzly bear to go down in history was the one that killed a French-Canadian trapper nicknamed “Lolo,” in about 1852. That encounter occurred along the ancient Indian trail the Corps of Discovery traversed, about twenty miles west of Travelers’ Rest, near the northeast corner of a vast territory which a contemporary cartographer labeled simply “Unexplored.”[2]Reports of Explorations.

We can only infer from anecdotal mortality counts at the beginning of the 20th-century that there once was a large population of grizzlies in the region now bounded on the north by Interstate 90 and on the south by Interstate 84.

The principal river drainages in this region are the Clearwater, which Lewis and Clark called the Kooskooskie, and the Snake, which they named Lewis’s River, whose headwaters contained the spawning beds (called redds) of huge migrations of four species of anadromous Salmonids that the explorers first described for scientists.[3]Bud Moore, The Lochsa Story: Land Ethics in the Bitterroot Mountains (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press, 1996), pp. 265-78. The grizzlies thrived on these, along with rodents, berries, tubers and insects between fish feasts; there were no bison or elk in the Bitterroot Mountains.

The main watershed of the Clark Fork of the Columbia is north and east of the Bitterroot Ecosystem. Historically, as far as fisheries biologists have been able to determine, it has never harbored any salmon runs, for the same reason that Lewis suspected—high waterfalls downstream—and there were few if any bison anywhere in it after the turn of the 19th Century. Thus, with better subsistence for grizzlies west of the Bitterroot Divide, it is not surprising that the Corps of Discovery did not encounter any of them in the Lemhi, Salmon, or Bitterroot Valleys, or even among the high mountain ridges where the Indian trail led them.

After the mid-1800s, as settlers moved into the boundary valleys, and with the beaver market diminished since the 1840s, trappers like Lawrence began harvesting grizzlies along with other furbearers—marten, lynx, mink, and ermine. By the early 1900s trappers may have been taking twenty-five to forty grizzlies annually. Meanwhile, trophy hunters entered the scene.

After the huge forest fires of 1910 and 1934 changed the forest face of the Northern Rockies, the Bitterroots became a commercial arena, as thousands of cattle and sheep were grazed on the new ground cover among the burned snags. Naturally, herders perforce armed themselves against the appetites of the grizzlies. In 1910 a dam was built near the mouth of the South Fork of the Clearwater, and in 1927 another was erected near the mouth of the main Clearwater River at Lewiston, Idaho, just above its confluence with the Snake. These barriers virtually closed the Clearwater to spawning salmon. Although the first dam was removed in 1963, and the Lewiston dam in 1973, six new dams on the Snake and Columbia have further inhibited anadromous lifestyles.

In 1971 Dworshak Dam, at the mouth of the North Fork of the Clearwater—almost directly opposite the Corps of Discovery’s “Canoe Camp” of 26 September 1805–7 October 1805—closed off 627 miles of salmon and steelhead trout spawning and rearing habitat in the northern third of the Bitterroot ecosystem. Hatchery-bred kokanee, which are landlocked sockeye salmon, have been introduced into the reservoir, with uneven success. In any case, their presence will not serve a grizzly population in the recovery area.

Federal and state hatcheries aim to restore chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytsha) and steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) into the Clearwater drainage, and the Nez Perce Tribe is working to restore fall chinook and coho salmon into the lower Clearwater River drainage.

Driven from the mountains by hunters, and deprived of seasonal salmon runs, the few remaining grizzlies invaded the valley floors, where they were the losers in their inevitable conflicts with humans.

The last grizzly track to be seen in the Bitterroot Mountains was recorded in 1946. That was the first year the Idaho Fish and Game Department prohibited grizzly hunting.

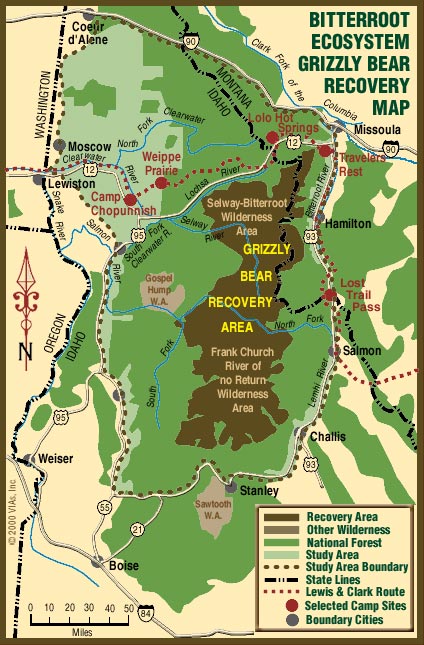

Recovery Plan

On 17 November 2000, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced its decision to release five grizzly bears into the 7,000-square-mile recovery area–the combined Selway-Bitterroot and Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness Areas–during each of five years beginning in the summer of 2002. They expect it will take between 50 and 100 years to reach the region’s carrying capacity of 280 to 300 grizzlies.

A committee of citizens appointed by the governors of Montana and Idaho, will “manage” the grizzly bear recovery process. Some critics approve of this feature of the plan, since it seems to represent a move away from bureaucratic management–keeping the government out of local issues. Opponents predict that it will politicize the management process more deeply than would a responsible government agency because special interests with major political clout will be served best, and the citizens who live nearest the boundaries of the study area may be powerless.

There are doubts and fears. Doubts that the soils in the Bitterroot ecosystem (BE) are of a quality that can support tubers as copiously as the Yellowstone ecosystem, where grizzlies have thrived. Doubts that habitat analysis based on satellite imagery, on which reintroduction plans have been based, will be confirmed by “ground-truthing.” Doubts that reintroduction into the BE is really necessary in order to “save the grizzly bear.” Grizzly bear foods include elk and deer, small mammals, herbaceous vegetation and tubers, and fruits and nuts. Research indicates that over 60% of known herbaceous, and nearly 80% of known fruit and nut food items consumed by grizzly bears still occur in the BEA (Bitterroot Evaluation Area). Opponents of the reintroduction point out that noxious weeds, unpalatable to wildlife, are monopolizing the best soils.

Although seasonally there may be sufficient quantities of spawning coho, and sockeye salmon for grizzly food, chinook salmon, which probably provided the bears’ main food source in the 1800s, are practically nonexistent now. In any case, owing to the presence of downstream dams on the Snake and Columbia Rivers, it is believed that anadromous fish would not be a readily available resource every year, and would only be supplemental at best. Therefore, the bears to be transplanted to the Bitterroot ecosystem will be chosen from populations with no particular fondness for fish.

There are fears that, although grizzlies are remarkably adaptive, and may multiply in spite of the virtual lack of whitebark pine seeds and spawning salmon in the BE, that same adaptability may impel them to migrate far beyond the official boundaries of the recovery area into human habitats such as those along the Lochsa River. Not only would recreational backcountry use within the wilderness areas be affected, but, worst of all, there could be human casualties both inside and outside the study area.

Chris Servheen, the federal government’s grizzly bear recovery coordinator, acknowledges the fundamentally controversial nature of both the concept of re-introduction and the plan for carrying it out. “Nobody,” he says, “has no opinion about grizzly bears.”

Online References

Notes

| ↑1 | Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the most Practicable and Economical Route for A Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Made under the direction of the Secretary of War, in 1853-4, According to Acts of Congress of 3 March 1853, 31 May 1854, and 5 August 1854. Vol. I (1855), Map No. 3. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Reports of Explorations. |

| ↑3 | Bud Moore, The Lochsa Story: Land Ethics in the Bitterroot Mountains (Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press, 1996), pp. 265-78. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.