Mystery Noises

repeatedly witnessed a nois which proceeds from a direction a little to the N. of West as loud and resembling precisely the discharge of a piece of ordinance of 6 pounds at the distance of three miles. I was informed of it by the men several times before I paid any attention to it, thinking it was thunder most probably which they had mistaken. At length, walking in the plains the other day I heard this noise very distinctly. It was perfectly calm, clear, and not a cloud to be seen.

“I am at a loss to account for this phenomenon,” he mused, but he reassured himself with the confidence of a true son of the Enlightenment: “I have no doubt but if I had leasure I could find from whence it issued.”

On 31 July 1805, Meriwether Lewis recorded two more discharges of this “unaccountable artillery of the Rocky Mountains.” He recalled that Pawnee and Arikara Indians far down the Missouri had mentioned just such a mysterious noise coming from the Black Hills in present-day South Dakota, but he had paid no attention, supposing the rumor to be either false or “the fantom of a supersticious immagination.” The trader Jean Vallé, whose house at the mouth of the Cheyenne River they visited the previous October, had also told them that near the river’s sources in the Black Hills “a great noise is heard frequently.”

William Clark summarized Lewis’s notes on the matter. “It is probable,” he added, “that the large river just above those Great falls which heads in the derection of the noise has taken it’s name Medicine River [today’s Sun River] from this unaccountable rumbling sound, which like all unacountable thing with the indians of the Missouri is Called Medicine.”[1]Donald Jackson, ed, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), p. 565. After the expedition ended, there was some more discussion about it between Clark and Nicholas Biddle, the editor of the History of the Expedition. On 20 December 1810, Clark wrote to Biddle: “I think I mentioned having heard a rumbling noise at the Great Falls of the Missouri, which was not accounted for, and you accounted for them by similating them to Avelanches of the Alps.” Biddle must have had second thoughts about his own suggestion, however, for no such notion appeared in the History, which was published in 1814.[2]Paul Allen, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific … Continue reading

The sound of “artillery” continued to startle travelers in the West. The information the Pawnees and Arikaras gave to Lewis was reconfirmed in 1810 by Wilson Price Hunt, who was in charge of John Jacob Astor’s Pacific Fur Company expedition to the mouth of the Columbia River. Meriwether Lewis’s younger contemporary, Washington Irving (1783-1859), who related the account in his history of the Astor family, Astoria, said that Hunt reported a “natural phenomenon of a singular nature” in the vicinity of the Black Hills. Similar sounds, Hunt remarked, had been heard in several parts of Brazil by a Jesuit priest named Vasconcelles, who was told by the Indians there that it was “the throes and groans of the mountain endeavoring to cast forth the precious stones hidden within its entrails.” In fact, Irving continued, “these singular explosions have received fanciful explanations from learned men, and have not been satisfactorily accounted for even by philosophers.”[3]Washington Irving, Astoria, Or Anecdotes of an Enterprize Beyond the Rocky Mountains, in Richard Dilworth Rust, ed., The Complete Works of Washington Irving (1836; reprint, Boston: Twayne … Continue reading

Other Historical Accounts

An anonymous writer for the Quarterly Review of London, in a long synopsis of Nicholas Biddle’s edition of the Journals, had done his homework, and so he set the record straight.[4]The Quarterly Review (London, 1815) Vol. XII: Oct. 1814 & Jan. 1815, pp. 343-44 “Upon this subject we happen to have collected some testimonies, which, as (being thus confirmed) they place the fact beyond all doubt, may, perhaps, if brought together, call the attention of philosophers to this phenomenon.” His first appeal was to the observations of the Portugese historian Simão de Vasconcelles (1597-1671) in Brazil. The Jesuit:

. . . describes one which he heard in the Serra de Piratininga [in southern Brazil], as resembling the discharges of many pieces of artillery at once. The Indians who were with him told him it was ‘an explosion of stones’; ‘and it was so,’ he says; ‘for after some days the place was found where a rock had burst, and from its entrails with the report which we had heard, like the groans of parturition, had sent to light a little treasure. This was a sort of nut, about the shape and size of a bull’s heart, full of jewelry of different colours, some white, like transparent chrystal, others of a fine red, and some between red and white, imperfect, as it seemed, and not yet completely formed by nature. All these were placed in order, like the grains of a pomegranate, within a case or shell harder than even iron; which, either with the force of the explosion, or from striking aginst the rocks, when it fell, broke in pieces, and thus discovered its wealth.’

Vasconcellos concluded, “the philosophy of these things is understood,” . . . but it is not necessary to dwell on his “philosophy” here.

Next, the anonymous authority summoned the testimony of Nicholás del Techo (1611-1684), a Jesuit missionary in Paraguay.

Techo notices the same thing in the adjoining province of Guayra, “famous,” he says, “for a sort of stones which nature, after a wonderful manner, produces in an oval stone case, about the bigness of a man’s head. These stone cases lying under ground, when they come to a certain maturity, fly like bombs in pieces about the air, with much noise, and scatter about abundance of very beautiful stones,—but these stones are of no value.”

The Spaniard Christoval d’ Acuña (1597-1675), a Jesuit missionary to Chile and Peru who accompanied Pedro Texiera on his exploration of the Amazon River in 1638, is the next observer to be cited.

In the account of Texiera’s voyage down the Orellana [Ecuador], d’ Acuña says, the Indians assured them, that “horrible noises were heard in the Serra de Paraguaxo from time to time, which is a certain sign that this mountain contains stones of a great value in its entrails.”

The opinion of the Indians then, concerning these explosions seems uniformly to refer them to the same cause: but what these natural grenades may be, must be left for others to ascertain.

Finally, the same unnamed author dismissed the speculation of Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), the German naturalist and explorer who, at his own expense and with only the companionship and assistance of the French botanist Aimé Bonpland, completed a five-year, 6,000-mile scientific exploration of Central and South America.

Humboldt, noticing a remark of M. Lafond, that there are hills in Mexico, abounding in coal, from which a subterraneous noise is heard at a distance, like the discharge of artillery, asks, whether “this curious phenomenon announces a disengagement of hydrogen produced by a bed of coal in a state of inflammation?”—It seems too frequent and too general for this solution

Moodus Noises

Twenty years before Lewis and Clark documented the “artillery of the Rocky Mountains,” Daniel Jones of the American Academy of Arts and Science studied similar occurrences near West-River Mountain in New Hampshire. Jones remarked that “the peasants . . . became pussessed with the idea of gold.”[5]“An Account of West-River Mountain,”Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1784, Vol. I, pp. 312-15; cited in Sandra Claflin-Chalton and Gordon J. MacDonald, Sound and … Continue reading Earlier in Colonial days, booming sounds were occasionally heard a few miles south of present-day Hartford, Connecticut, at a place local Indians named Moodus, meaning “strange noises.”[6]K. W. Golde in The Foretan, October 1941, p. 7; from the Buffalo Evening News of 2 March 1940. Cited in William R. Corliss, comp. Strange Phenomena: A Sourcebook of Unusual Natural Phenomena (2 … Continue reading

While crossing the Canadian Rockies in the spring of 1807, David Thompson observed: “The Mountains are loaded with Snow,the continual rushing down of which makes a Noise like Thunder.”[7]7 June 1807. Barbara Belyea, ed., Columbia Journals: David Thompson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 42. Similarly, Alexander Henry attributed the startling explosions to avalanches. “[On] perpendicular summits, so steep that no human being could ascend them, . . . I observed an emmense depth of snow, where a part seems lately to have seperated and fell down the Mountain . . . . The noise occasioned by the fall of such a great body of Snow will cause an explosion equal to loud Thunder, as it sweeps away every thing that is moveable in it[s] course to the vallies below.”[8]Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater North West: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry and of David Thompson. 3 vols. (New York: F. P. Harper, 1897), 2:689.

In 1872 the Northern Pacific railroad sent Thomas P. Roberts to Montana to conduct a survey of the upper Missouri River, and map a right-of-way for a proposed narrow-gauge railroad around the Great Falls of the Missouri. On 7 August, when Roberts and his party were camped at the mouth of the Sun River, they recognized sounds similar to those Lewis and Clark had reported. “Altogether,” he confided to his journal, “there was something strange in the coincidence.”[9]Thomas P. Roberts, Report of a Reconnaissance of the Missouri River in 1872 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875), 49. During the 1890s, scientists in Nova Scotia and England put out calls for accounts of the phenomenon, and responses came from all corners of the globe. Each locality had its own name for the sounds.[10]W. F. Ganong, “Upon Remarkable Sounds Like Gun Reports Heard Upon Our Southern Coast,” Bulletin of the Natural History Society, New Brunswick, Canada (1897), 40. Also G. H. Darwin, in … Continue reading Cornwall thumps (Ontario); water guns of Lough Neagh (Ireland); detonations of Comrie (Scotland); the sounds of Morecombe Bay (England). British officials at Barisal in Bangladesh, near the mouth of the Ganges River, termed them Barisal Guns. Nova Scotians referred to air quakes or sea farts; Haitians called them gouffre, Italians knew them as baturlio marina, and Hollanders and Belgians said mist poeffers. In central New York state they were the guns of Lake Seneca; in the Florida Gulf, just “air sounds.” Natives around Lake Bosumtwi, in West Africa, said Bosumtwi oto atuduru; “Bosumtwi has fired gunpowder!” They’ve startled people in Syria, Egypt, and Constantinople; in Switzerland, Provence, Alsace, Tuscany, Burgundy and Paris; in Lapland and the Eastern Himalayas.[11]See Corliss, passim; also Encarta (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation, 1994), s.v. Barisal guns.

The most recent reports of sonic anomalies were recorded between 2 December 1977, and 31 May 1978. Nearly 600 separate “mystery booms” were heard along the east coast of North America, from Nova Scotia to Charleston.

They elicited enough fear and anxiety among American taxpayers to prompt Senator Harrison Williams of New Jersey to demand a Congressional investigation, and the Naval Research Laboratory was given the assignment. The NRL estimated that two-thirds of the “events” were caused by supersonic aircraft; the rest were ascribed to “unknown causes.”

An analysis of the NRL report by two east-coast researchers led to the conclusion that the majority of the unattributed noises had a natural origin, possibly but not necessarily associated with earthquakes.[12]Sandra Claflin-Chalton and Gordon MacDonald. See note 1. Recently a suggestion was made to Professor MacDonald that he and his co-author bring their book up to date, but there was insufficient new data to make the effort worthwhile.[13]Personal communication, 29 November 1994. It seems that an impenetrable pall of noise pollution, dominated by sirens and jet engines, has obliterated such experiences from our ken.

Brontides or P Waves?

Modern lexicographers have tried to fix a scientific name on this strange but ubiquitous sonic event, but it has not taken hold. The word brontides, from the Greek words bremein (roar), and bromos (loud noise), appeared in the 1971 edition of Webster’s Third International, with a definition no more precise than that of Lewis, Clark or Fr. Vasconcelles: “a low muffled sound like distant thunder heard in certain seismic regions esp. along seacoasts and over lakes and thought to be caused by feeble earth tremors.”[14]Webster’s Third International Dictionary (Springfield, Massachusetts: G. & C. Merriam Company, 1971). It appeared again two years later in a dictionary of scientific terms bearing a less equivocal explanation: “Low, thunder-like noise, of short duration, most frequent in actively seismic regions; it is the rumbling of a very feeble earthquake.”[15]Robert W. Durrenberger, comp., Dictionary of the Environmental Sciences (Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books, 1973).

The Encyclopedia Britannica, in its CD97™is silent on the subject of brontides, but explains that one of the four waves of energy accompanying an earth tremor—specifically, a “body wave” called a “P [for Primary] wave”—resembles a sound wave. It is a compressional or longitudinal seismic wave near the earth’s surface which gives back-and-forth motion to rock particles along the path of the tremor.

The implication is that when the energy of the subterranean stretching and compression reaches the surface, it sets the air above in motion, producing a short, low sound. This theory was first propounded in 1936, in a study of a recent earthquake at Helena, Montana.[16]F. P. Ulrich, “Helena Earthquakes,” Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, Vol. 27 (1936), pp. 323-339. That would be sufficient to satisfy a Lewisian curiosity, were it not for the fact that the vicinity of Great Falls, Montana, is an area of low potential for earthquakes. The men of the Corps of Discovery would more likely have heard the effects of P waves in the vicinity of the Three Forks of the Missouri, 200 river miles upstream.

Thunderclaps?

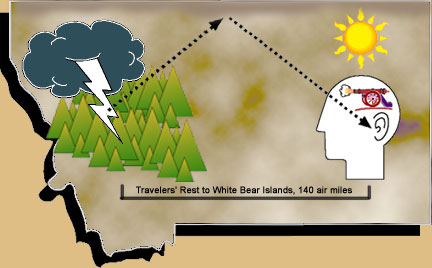

In 1977 physicist Jearl Walker offered a more plausible explanation than the P wave theory. Thunder! Loud sounds such as explosions or thunder normally die away to inaudibility at a distance of about 15 miles, so even if one could see distant thunder clouds above mountainous terrain, one would not necessarily hear the accompanying thunder. However, the normally inverse ratio of temperature to altitude can be turned upside down by a frontal inver-sion, in which a cold air mass is driven under warm air, forcing the latter up-ward.[17]Encyclopædia Britannica Online (accessed 18 November 2001), s.v. “Temperature inversion.” The thunderclap that accompanies lightning begins close to the ground, radiating sound waves outward and upward. Walker explained:

The speed of sound in air increases as the air temperature increases. Thus, as the sound wave reaches the increasingly warmer air in the stratosphere, the higher portion of the wave will travel faster than the lower portion, causing the wave path to bend over and eventually turn downward. Sound will be heard where it reaches the ground.[18]Jearl Walker, The Flying Circus of Physics, with Answers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1977), pp. 227-28. See also E. G. Richardson, “Sound and the Weather,” Weather (London: Royal … Continue reading

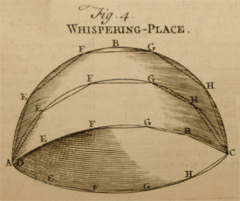

The effect is similar to that of a whisper gallery in a science museum, where two people separated by a considerable distance beneath a parabolic ceiling that is low at both ends and high in the middle, can converse at a whisper, but cannot be heard by persons standing between them.

The phenomenon continued to attract the attention of acousticians and meteorologists throughout the second half of the 20th century. In 2001, what may be the last word on the subject appeared in the book Civil War Acoustic Shadows, by Charles D. Ross.[19]Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Books, 2001. Surprisingly, the facts on which it was based had first been recorded immediately after the battle at Gaines’s Mill near Richmond, Virginia, on 27 June 1862. Two observers—the Confederate Secretary of War, George Wythe Randolph, and a member of his staff—had stood within a mile and a half of the action and could see the smoke from muskets and the flash of cannon fire, but had not heard a sound, yet the noise of that same battle was clearly heard as far away as 140 miles west of the conflict.

Comparable acoustic anomalies were witnessed in several ensuing engagements, and actually affected battlefield tactics and outcomes. Furthermore, the same coincidence of silent zones with long-distance audibility of gunfire was recorded several times during World War I.

Conclusion

“Hence it is, that sound is conveyed from one side of a whispering-gallery to the opposite one, without being perceived by those who stand in the middle. . . . Let ABC represent the segment of a sphere; and suppose a low voice uttered at D, the vibrations expanding themselves every way, some will impinge upon the points E, C, &c. and from thence be reflected to the points F, from thence to G, and so on till they all meet in C.”

Thus a clearly reasonable explanation for what Lewis described as the “unaccountable artillery of the Rocky Mountains,” is based on a combination of acoustic shadows and sound reflectance, or lensing, has been known for nearly 150 years. In fact, Lewis had the key to the solution at his very fingertips. In Owen’s Dictionary, the encyclopedia he had brought along on the expedition, was an illustrated article titled “Whispering Places,” including descriptions of well-known examples located in two English cathedrals.[20]A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1754), s.v. “Whispering places.” Had Lewis found the “leasure” to ponder the principle, he might have imagined the correlation between a whispering-gallery and the terrestrial atmosphere.

On the other hand, Washington Irving’s decidedly post-Enlightenment perspective toward the question is still worth bearing in mind:

In whatever way this singular phenomenon may be accounted for, the existence of it appears to be well established. It remains one of the lingering mysteries of nature which throw something of a supernatural charm over her wild mountain solitudes, and we doubt whether the imaginative reader will not rather join with the poor Indian in attributing it to the thunder spirits, or the guardian genii of unseen treasures, than to any commonplace physical cause.

Well, perhaps the “commonplace physical cause” of this mysterious phenomenon has indeed been settled once and for all. On the other hand, why not throw in with Washington Irving’s “poor Indian” and his “supersticious immagination”?

Do we really need to know all the answers?

This article is based on Joseph Mussulman, Soundscapes: The Sonic Dimensions of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, We Proceeded On, Volume 21, No. 4 (November 1995), the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original article is available at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol21no4.pdf#page=13.

The author acknowledges Ted Kaye, Oregon History Center, for his help with Other historical accounts. Joseph Mussulman and David E. Nelson, with help from Prof. Michael Stickney, Earthquake Studies Office, Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Butte, co-authored Thunderclaps.

Notes

| ↑1 | Donald Jackson, ed, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), p. 565. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paul Allen, History of the Expedition Under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark, to the Sources of the Missouri, Thence Across the Rocky Mountains and Down the River Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814). |

| ↑3 | Washington Irving, Astoria, Or Anecdotes of an Enterprize Beyond the Rocky Mountains, in Richard Dilworth Rust, ed., The Complete Works of Washington Irving (1836; reprint, Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1976), I:167. In the 18th century a philosopher was, in general, a learned person or a scholar. Adam Smith (1723-1790), the Scottish student of political economy, described philosophers as “men of speculation, whose trade is, not to do any thing, but to observe every thing.” Smith, An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations (1776); Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication, p. 15. |

| ↑4 | The Quarterly Review (London, 1815) Vol. XII: Oct. 1814 & Jan. 1815, pp. 343-44 |

| ↑5 | “An Account of West-River Mountain,”Memoirs of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1784, Vol. I, pp. 312-15; cited in Sandra Claflin-Chalton and Gordon J. MacDonald, Sound and Light Phenomena: A Study of Historical and Modern Occurrences (McLean, Virginia: The MITRE Corporation, 1978), 75. |

| ↑6 | K. W. Golde in The Foretan, October 1941, p. 7; from the Buffalo Evening News of 2 March 1940. Cited in William R. Corliss, comp. Strange Phenomena: A Sourcebook of Unusual Natural Phenomena (2 vols.; Glen Arm, MD: William R. Corliss, 1974), I:GSD [Geology-Sounds-Detonations], item 013. Following a series of microearthquake swarms during the 1980s, scientists sank boreholes in the “Moodus quadrangle,” but the results of the research contain no references to the mysterious sounds. |

| ↑7 | 7 June 1807. Barbara Belyea, ed., Columbia Journals: David Thompson (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 42. |

| ↑8 | Elliott Coues, New Light on the Early History of the Greater North West: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry and of David Thompson. 3 vols. (New York: F. P. Harper, 1897), 2:689. |

| ↑9 | Thomas P. Roberts, Report of a Reconnaissance of the Missouri River in 1872 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1875), 49. |

| ↑10 | W. F. Ganong, “Upon Remarkable Sounds Like Gun Reports Heard Upon Our Southern Coast,” Bulletin of the Natural History Society, New Brunswick, Canada (1897), 40. Also G. H. Darwin, in Nature (31 October 1895) 52:650. George Howard Darwin was a son of Charles Darwin. |

| ↑11 | See Corliss, passim; also Encarta (Redmond, WA: Microsoft Corporation, 1994), s.v. Barisal guns. |

| ↑12 | Sandra Claflin-Chalton and Gordon MacDonald. See note 1. |

| ↑13 | Personal communication, 29 November 1994. |

| ↑14 | Webster’s Third International Dictionary (Springfield, Massachusetts: G. & C. Merriam Company, 1971). |

| ↑15 | Robert W. Durrenberger, comp., Dictionary of the Environmental Sciences (Palo Alto, CA: National Press Books, 1973). |

| ↑16 | F. P. Ulrich, “Helena Earthquakes,” Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, Vol. 27 (1936), pp. 323-339. |

| ↑17 | Encyclopædia Britannica Online (accessed 18 November 2001), s.v. “Temperature inversion.” |

| ↑18 | Jearl Walker, The Flying Circus of Physics, with Answers (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1977), pp. 227-28. See also E. G. Richardson, “Sound and the Weather,” Weather (London: Royal Meteorological Society), Vol. 2 (June 1947), 169–73, 205–10; and Martin A. Uman, Lightning (New York: Dover, 1969), 196-98. |

| ↑19 | Shippensburg, Pennsylvania: White Mane Books, 2001. |

| ↑20 | A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1754), s.v. “Whispering places.” |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.