There is no known image of Sacagawea that was made of her during her lifetime, so no one can be sure what she really looked like. Yet because the Lemhi Shoshone woman has been the subject of so many statues and paintings, especially since about 1900, we have a rich heritage of artists’ conceptions to contemplate. Meriwether Lewis, in his journal entry for 19 August 1805, left us a brief description of the general physical appearance of the Shoshone people, including their manner of dress. Some artists have taken it into account, others not.

Visual images of Sacagawea will be the primary focus of this episode, and more will be added to the gallery as we acquire them. but some short essays also will be introduced from time to time. Topics will include her name—its spellings, pronunciations, and possible meanings; her role in the Lewis and Clark expedition as an interpreter; her own work; and her her return home and her later years; and the history of the controversies surrounding the largely fictitious persona that scant facts have engendered. See, for example, The Hidatsa Story of Sakakawea, a legend about her life and death. Also, there’s the long and increasingly bitter history of the noun by which Lewis and Clark occasionally referred to her in their journals—squaw.

Plentywood, Montana

Sacagawea, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, and Seaman

Miniature by Michael Westergard, 1998

Photography by David Nelson

Michael Westergard and his wife Patricia operate the Westergard-Ragucci Bronze Studio in Plentywood, a small town in the extreme northeast corner of Montana, north of the Fort Peck Assiniboine/Sioux Indian Reservation. His bronzes portray the history, wildlife and people of the American West with accuracy of detail and respect for the subject.

His work can be seen throughout the United States, Canada, and Europe, including the collection of Lord Friederick Wilhelm of Wied (Germany) a descendent of Prince Maximilian, who led the Maximilian/Bodmer expedition up the Missouri River in 1833-34. His bronzes are also in the permanent collections of the National Park Service and the Favell Museum in Klamath Falls, Oregon. The most extensive collection of his work is at the Michael Harrison Western History Research Center of the University of California at Davis.

Sakakawea and Jean-Baptiste

by Leonard Crunelle

Bismarck, North Dakota

Created 1910, Capitol grounds, Bismarck, North Dakota. J. Agee photo.

This spelling has been attributed to Nicholas Biddle, the editor of the first edition of the expedition’s journals (1814), who read the captains’ usual orthography as a soft g (as in gem, or gentle), and replaced their g with a j.

Meriwether Lewis understood her Hidatsa name to mean “bird woman”—saca, “bird” and wea, “woman. On 20 May 1805, he wrote that they had named a tributary of the Musselshell River “bird woman’s River, after our interpreter the Snake [Indian] woman.”

The photographer of the view above (right) had just raised his camera to his eye when a bird obligingly alighted on Bird Woman’s head, as if to reaffirm her name in behalf of all bird-dom. Obviously, many other avians had similarly anointed her brow.

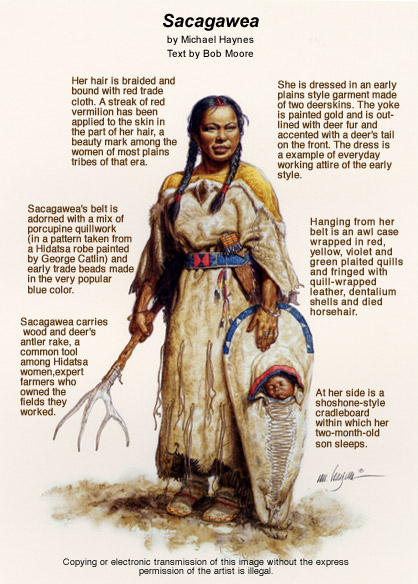

Sacagawea

Copying or electronic transmission of this image without the express permission of the artist is illegal.

Copies of this print are available direct from the artist.

On 19 August 1805, while at Camp Fortunate near the headwaters of the Beaverhead River, Lewis wrote of Sacagawea’s people, the Shoshone Indians:

Notwithstanding their extreem poverty they are not only cheerfull but even gay, fond of gaudy dress and amusements. . . .

These people are deminutive in stature, thick ankles, crooked legs, thick flat feet and in short but illy formed, at least much more so in general than any nation of Indians I ever saw. their complexion is much that of the Siouxs or darker than the Minnetares [Hidatsas], mandands [Mandans] or Shawnees. generally both men and women wear their hair in a loos lank flow over the sholders and face. . . . the cue is formed with thongs of dressed lather or Otterskin alternately crossing each other. . . . the ornaments of both men and women . . . consist of several species of sea shells, blue and white beads, bras[s] and Iron arm bands, plaited cords of the sweet grass, and collars of leather ornamented with the quills of the porcupine dyed of various colours among which I observed the red, yellow, blue, and black.

Sacajawea and Jean-Baptiste

Washington Park, Portland, Oregon

Unveiled 6 July 1905; Moved to Washington Park, 6 April 1906.

J. Agee photo.

Sacagawea and Jean Baptiste

by Glenna Goodacre

Lewis and Clark College, Portland, Oregon

Both photos by VIAs Inc.

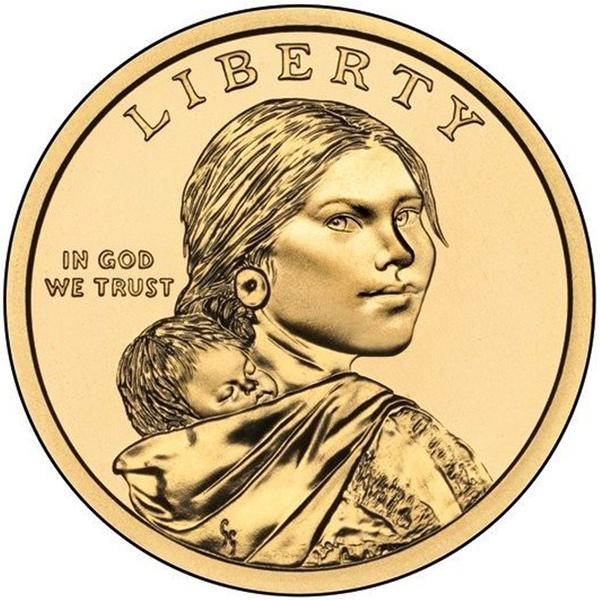

Glenna Goodacre also designed the gold dollar coin, using the same model, Randy’L He-dow Teton, a Lemhi Shoshone who was a student at the University of New Mexico in 1998.

Bruno Zimm (1876-1943) was a sculptor and an architect who worked in the neoclassical style that was popular at the end of the 19th century. He studied under Augustus Saint Gaudens (1848-1907), the most prominent American sculptor of the late 19th century. So far as is known, this statue, which was cast of a material called staff—a mixture of plaster and fiber over a wooden frame—is no longer in existence.

The handsome young Shoshone girl carries little Jean Baptiste not on a cradleboard but in the Hidatsa Indian manner, wrapped in a buffalo robe, facing forward over his mother’s shoulder. The Hidatsas—Lewis and Clark knew them as Minitaris—were farmers as well as hunters, and their women were responsible for raising corn, beans, and so forth. Babies were carried this way so the sun wouldn’t be in the infants’ eyes when their mothers bent over to pull weeds or harvest vegetables.

This photograph, taken by the artist, was printed as the frontispiece to John C. Luttig’s Journal of a Fur-Trading Expedition on the Upper Missouri 1812-1813, edited by Stella M. Drumm (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1920).

Sacajawea by Carole Grende

Lewis and Clark State College, Lewiston, Idaho

© 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Sacagawea Golden Dollar Coin

Obverse

© 2022 by WikiCommons user Tommy5544. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This design by Glenna Goodacre and modeled by Shoshone Randy’L He-dow Teton has fronted the Sacagawea Golden Dollar and Native American $1 coins since 2000. By featuring Sacagawea in three-quarter profile, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau can be seen in a sling on her back. Following Shoshone legend, she has been given large, dark eyes.[1]“Sacagawea Golden Dollar Coin,” United States Mint, accessed 22 May 2023, www.usmint.gov/coins/coin-medal-programs/circulating-coins/sacagawea-golden-dollar.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Sacagawea Golden Dollar Coin,” United States Mint, accessed 22 May 2023, www.usmint.gov/coins/coin-medal-programs/circulating-coins/sacagawea-golden-dollar. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.