Triumphant at the Source

Hugh McNeal Exulting at the Headwaters

© Michael Haynes, Michael Haynes, Historic Art

That this creek is the second-highest source of the Missouri River after Red Rock Creek is best left for other moments.

The eternal image of Hugh McNeal is of a man celebrating, triumphantly standing astride tiny Horse Prairie Creek just below Lemhi Pass at the present border between Montana and Idaho. On 12 August 1805, Captain Meriwether Lewis, McNeal, George Drouillard, and John Shields were working their way up hill, following a tributary of the Missouri River. Lewis wrote:

. . . McNeal had exultingly stood with a foot on each side of this little rivulet and thanked his god that he had lived to bestride the mighty & heretofore deemed endless Missouri.

The day before this celebration, McNeal was at Lewis’ side when the Captain’s advance party had their first glimpse of a Shoshone, a tribe they had been long seeking. McNeal’s presence with Lewis in this advance party speaks well of the private’s standing in the Corps of Discovery.

Beginnings

Hugh McNeal was likely born in Pennsylvania about 1776. His name first appears in the Expedition journals in Captain William Clark‘s notes written in early January 1804 at Camp River Dubois. On 1 April 1804, Clark noted that McNeal had been assigned to the expedition’s permanent party, in the Second Squad under the command of Sergeant Charles Floyd (and later Sergeant Patrick Gass).[1]Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 159, 196.

McNeal’s Folly

McNeal is one of the men who enjoyed the company of native women during the expedition, and one night it almost cost him his life. In January 1806, McNeal was in Clark’s party that traveled overland from Fort Clatsop to see the beached whale on the Pacific at NeCus’ Village, where they traded for blubber that the Tillamooks were harvesting. On their return trip to Fort Clatsop, the party stopped at the salt works where other expedition men were making salt.

On the evening of 8 January 1806 Indians at the nearby Chinook village raised a sudden alarm. Clark, determining that McNeal was absent, sent Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor and four men to his rescue. McNeal was visiting a Clatsop woman in her village when a Tillamook man invited McNeal to his lodge “to get Something better.” McNeal’s hostess, who had just served him some blubber, grabbed McNeal’s blanket to warn him not to go with the Tillamook man, then alarmed her village. Clark said that it was a “premeditated plan of the pretended friend of McNeal to assanate him for his Blanket and what few articles he had about him . . . .” Later, according to Sergeant John Ordway and Private Joseph Whitehouse, Clark named present Ecola Creek, “McNeal’s Folly.”

McNeal’s life was saved that night, but in the long run, it may have been taken by Chinook liaisons. By the end of January, McNeal (and Silas Goodrich) had “the pox,” or syphilis, which Lewis treated with mercury—the only treatment of the era–which affected only the symptoms. The Chinook women had most likely been infected by international sailors who visited the coast. On 20 February 1806, McNeal was worse, either from not continuing to apply the mercury ointment or from re-infection. He and Goodrich were deemed “recovered” that March, but by July, McNeal and Goodrich were “very unwell with the pox.” Lewis decided that both McNeal and Goodrich should be included in his detachment that would travel back to the falls of the Missouri so that they could rest and continue their mercury treatment.[2]See also on this site by David Peck, D.O.: Sulphur Springs.

Successful Trader

As the Expedition worked its way back toward St. Louis in 1806, they had depleted their Indian trade goods, and had to resort to extreme measures to bargain for food:

Our traders McNeal and York were furnished with the buttons which Capt. C. and myself cut off our coats, some eye water and Basilicon which we made for that purpose and some Phials and small tin boxes which I had brought out with Phosphorus. in the evening they returned with about 3 bushels of roots and some bread having made a successfull voyage, not much less pleasing to us than the return of a good cargo to an East India Merchant.

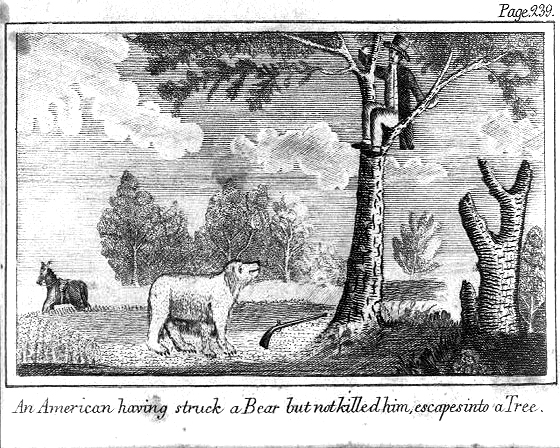

Up a Tree Without a Musket

McNeal Up a Tree

Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress

Patrick Gass, A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery, Under the Command of Capt. Lewis and Capt. Clarke (Philadelphia: Matthew Carey, 1812), 239.

The three Philadelphia editions of Patrick Gass’ journal (1810, 1811, and 1812) included six extraordinary engravings of highly-imaginative views of expedition, including one of “An American having struck a Bear but not killed him, escapes into a Tree.” Although the caption of the illustration did not identify him, he was indisputably Private Hugh McNeal.[3]Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 139.

As the Expedition was making its way back home, Captain Lewis and his party reached the Upper Portage Camp above the falls of the Missouri in mid-July of 1806. On 15 July 1806, Captain Lewis sent McNeal to travel on horseback to the Lower Portage Camp to determine the status of the white pirogue and the cache of items they had buried. Lewis wrote:

a little before dark McNeal returned with his musquet broken off at the breech, and informed me that on his arrival at willow run he had approached a white bear within ten feet without discover him the bear being in the thick brush, the horse took the allarm and turning short threw him immediately under the bear; this animal raised himself on his hinder feet for battle, and gave him time to recover from his fall which he did in an instant and with his clubbed musquet he struck the bear over the head and cut him with the guard of the gun and broke off the breech, the bear stunned with the stroke fell to the ground and began to scratch his head with his feet; this gave McNeal time to climb a willow tree which was near at hand and thus fortunately made his escape. the bear waited at the foot of the tree untill late in the evening before he left him, when McNeal ventured down and caught his horse which had by this time strayed off to the distance of 2 ms. and returned to camp.

Lost to History

After the expedition, McNeal disappeared from the historical record. Clark listed him as dead by 1825–1828. Nevertheless, his name lingered in the record because on 13 August 1805, the captains named a creek that flows into the Beaverhead River, at Dillon, Montana, for McNeal. Today it is known as Blacktail Deer Creek.[4]Morris, 250n34.

Notes

| ↑1 | Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 159, 196. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See also on this site by David Peck, D.O.: Sulphur Springs. |

| ↑3 | Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 139. |

| ↑4 | Morris, 250n34. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.