Early Years

A Newhampshireman, the brown-haired, dark-complexioned Willard was born 24 August 1778 at his father’s farm at Condon Corner—then the town of Charlestown in Cheshire County.[1]“Alexander Hamilton Willard, Sr., Willard Family Association, willardfamilyassociation.org; “Elexander Willard,” New Hampshire, U.S. Birth Records, 1631–1920, ancestry.com, both … Continue reading This was the time that the meteoric reputation of an eloquent and dedicated young patriot named Alexander Hamilton drew the attention and allegiance of infant Willard’s father, who proudly named his son in honor of the rising statesman.

Rounding the Point

Bronze relief at Dismal Nitch Safety Rest Station. Photo © 2012 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Above: Willard, George Gibson, and William Bratton attempt to go around Point Ellice on the Columbia River. See November 12, 1805.

Close Call

On 14 November 1805, Alexander Willard and George Shannon experienced one of the more fortunate coincidences that occurred during the entire Expedition. Because of the almost continuously stormy weather, visibility was so poor, and navigation in the heavily loaded dugout canoes they had left (one had been destroyed by waves that drove it against the rocks on the shore) that it was hard to determine whether to stay where they were or proceed on. George Vancouver’s chart of the Lower Columbia River was in such a small scale as to be virtually useless for navigation. With John Colter, they had left “Dismal Nitch” (east of Point Ellice, at today’s Megler Point, Washington) the previous day, assigned by Captain Clark to find a more sheltered harbor to camp in, and also to look for whites at a trading post or with a ship. Seeing neither any white men nor any place that seemed better than their present campsite east of “Point Distress,” or “Blustering Point,” Colter returned to camp with that report while Willard and Shannon pitched camp and awaited the main party. That night, while they were asleep on a “butifull Sand beech,” Indians stole their rifles almost from under their heads, according to Clark. The two men threatened the departing thieves—as Nicholas Biddle added, probably from Private George Shannon’s information[2]Shannon assisted Biddle in editing the journals.—with pursuit and retaliation by “a large party from above.” And then, in Clark’s account, “Capt. Lewis & party arrived at the Camp of those Indians at So Timely a period that the Inds. were allarmed & delivered up the guns &c.”

Court Martial

Willard had obviously redeemed himself since 12 July 1804, when he was court–martialled for “Lying down and Sleeping on his post whilst a Sentinal, on the night of the 11th. Instant.” According to the Rules and Articles of War, that was a capitol crime tantamount to desertion and punishable by death. However presumably because no dire consequences had resulted from it, he was sentenced instead to 100 lashes with a cat o’ nine tails.[3]William C. Hart, Observations on Military Law and the Constitution and Practice of Courts-Martial, (New York: Appleton & Co., 1864), pp. 244-245. An officer was to stand by and ascertain that each stroke was laid on with vigor. The purpose of a flogging was primarily to inflict pain and shame on the criminal, and to serve as a lesson to his comrades, who were required to witness the event. Therefore, ostensibly to somewhat lessen the purely physical effects of it, but also to protract the experience of the criminal and its effect on the onlookers, the sentence was usually carried out, as it was with Willard, on four successive days at sunset, 25 lashes each day, and strokes were separated by pauses equal to “three paces in slow time” as audibly measured out by drumbeats. (See also Courts Martial on the Trail.

Rank of Artificer

Willard joined the army in 1800 as an “artificer”—a craftsman; in his case, a blacksmith. At the age of 25, while on duty at Fort Kaskaskia in the Illinois country, he voluntarily enlisted in the Corps of Discovery. At times he apparently assisted John Shields, the expedition’s primary blacksmith. In July 1805 Clark selected Willard as one of five men to assist him in surveying and flagging the portage route around the Great Falls of the Missouri.[4]Moulton, ed., Journals, 4:305n1. After Clark’s party reached three islands a short distance above the falls, where they set up the temporary Upper Portage Camp,[5]The first, Lower Portage Camp, was at the mouth of Belt Creek downstream from the falls. Willard was dispatched on 18 June 1805 to pick up meat the hunters had left. Clark wrote that Willard was 170 yards from the islands when he “was attact by a white [grizzly] bear and verry near being Caught.” Clark immediately summoned three of the enlisted men and “prosued the bear” as it approached the islands and threatened Colter, who retreated into the Missouri River. After that, the general location of Colter’s crisis, which became the Corps’ camp above the falls, was known as “White Bear Islands.”

At Fort Clatsop, Willard suffered a mysterious illness from February through March 1806, complaining of headache, fever, and low spirits. He and William Bratton were sick at the same time, but unlike Bratton, Willard recovered on his own.

Horse Problems

Clark took Willard in his advance party that sought to buy horses as the Corps moved back up the Columbia River in the spring of 1806, and occasionally ordered him to carry word back to Lewis about the continuing failure to obtain affordable steeds. Even though well aware of how precious their few horses were, Willard was the man who failed to picket his own animal well enough at The Dalles on 19 April 1806. It wandered off during the night, and could not be found the next morning; the incident aroused Lewis’s wrath toward the private:

this in addition to the other difficulties under which I laboured was truly provoking. I repremanded him more severely for this peice of negligence than had been usual with me.

Years later, one of Willard’s sons would tell historian and suffrage activist Eva Emory Dye that, when reminiscing about the expedition his father “did not speak much of Lewis but he was a personal friend of Gov. Clark” after that.[6]Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 120-21, 174-75.

Long Swim

Lewis wrote with concern on 4 August 1806, when Willard was thrown into the Missouri River in eastern Montana. He and John Ordway had been hunting behind Lewis’s main party and were coming up after dark with the meat from a bear and two deer in their canoe. The current pushed it into a “parsel of sawyers,” or partially submerged trees, and Willard, the steersman, was swept out of it. Meanwhile, Ordway fought his way to shore a half mile downstream and returned by land. Willard had clung to a sawyer until he could tie some handy driftwood together as a float, then:

set himself a drift among the sawyers which he fortunately escaped and was taken up a mile below by Ordway with the canoe. . . . it was fortunate for Willard that he could swim tolerably well.

Willard was to survive another canoe mishap only 27 days later, in today’s South Dakota. During the night of 30 August 1806, a violent storm struck their camp, which was pitched on a sandbar. The men rushed to hang onto the boats to keep them from being blown away. The two canoes used by Sgt. Pryor and Sheheke‘s and René Jusseaume‘s families broke loose, one holding Weiser, the other Willard. They were blown ashore across the Missouri and, after the wind slackened were rescued by Sgt. Ordway and six men.

Long Life

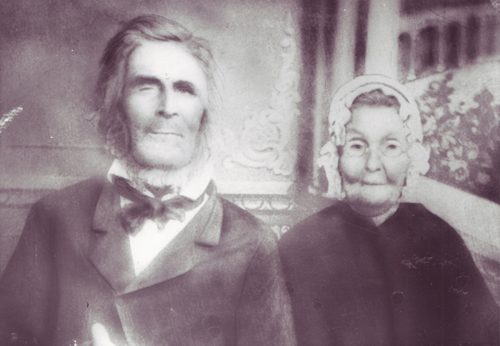

Back in Missouri, five months after the expedition’s end, Alex married Eleanor McDonald, a union that lasted 58 years, with Eleanor surviving him by three years. With Clark’s help he obtained work as a blacksmith for the Lenape Delawares and Shawnees in 1809. He also worked as a courier for Clark during the War of 1812. Eleanor bore twelve children, some of whom moved with their parents to Wisconsin in 1827. There, in 1836, their second son, George Clark Willard, was killed by a neighbor, who was convicted of manslaughter.

In 1852, at the first peak of westward migration, the extended Willard family joined a wagon train put together at Platteville, and moved to California. Alexander Willard, then 74, crossed the Missouri River for the final time at Council Bluffs, Iowa. He was 86 when he died in Sacramento,[7]Ibid., 172–74. the next-to-last survivor of the Corps of Discovery.

Notes

| ↑1 | “Alexander Hamilton Willard, Sr., Willard Family Association, willardfamilyassociation.org; “Elexander Willard,” New Hampshire, U.S. Birth Records, 1631–1920, ancestry.com, both accessed 25 October 2024. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Shannon assisted Biddle in editing the journals. |

| ↑3 | William C. Hart, Observations on Military Law and the Constitution and Practice of Courts-Martial, (New York: Appleton & Co., 1864), pp. 244-245. |

| ↑4 | Moulton, ed., Journals, 4:305n1. |

| ↑5 | The first, Lower Portage Camp, was at the mouth of Belt Creek downstream from the falls. |

| ↑6 | Larry E. Morris, The Fate of the Corps: What Became of the Lewis and Clark Explorers After the Expedition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 120-21, 174-75. |

| ↑7 | Ibid., 172–74. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.