Wheeler’s book was the result of several years promoting the Lewis and Clark Trail for the Northern Pacific Railroad. The book’s subtitle reveals what he want to accomplish: “A story of the great exploration across the Continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes ound a century later.”

Intersection

Photographer unknown. From Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark (1904), 1:159.

The first bridge across the Missouri River was completed in 1869 by the Missouri Pacific Railroad, at Kansas City. The Union Pacific completed this bridge between Omaha, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa, nine years later. The Northern Pacific Railway bridged the Missouri River at Bismarck/Mandan, North Dakota, 855 miles upriver from here, in 1882.

As these and other railroads threaded their separate ways through the American Northwest, they frequently extended short lines north and south to facilitate passenger and freight traffic into every valley and plain that offered the possibility of profit. “Here the railway must be the pioneer, the settler the follower,” Wheeler explained. Thus the real opening of the West to the American people at large began almost exactly fifty years after the expedition when, in 1856, the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad bridged the Mississippi River.

By the turn of the 20th century, Nicholas Biddle‘s 1814 paraphrase of Lewis and Clark’s journals had gone through some 40 reprints and editions, culminating in the intensive commentary by the historical editor and ornithologist Elliott Coues (1842-1899), which was published in 1893. Nine years later, Reuben Gold Thwaites (1853-1913) began transcribing the manuscripts of all known journals from the Lewis and Clark expedition, a monumental undertaking which he completed in less than three years; it was published in 1905. Clearly, both works were aimed toward a readership of serious students of the expedition.[1]For an account of Thwaites’s tribulations in publishing the first complete edition of the journals, see Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of … Continue reading

As the hundredth anniversary of the expedition approached, however, the first books about the expedition began to appear. Nellie F. Kingsley’s The Story of Captain Meriwether Lewis and Captain William Clark (1900), was intended for young readers, as was First Across the Continent (1901), by Noah Brooks. Brooks’s story was illustrated with 23 full-page drawings, including 8 by George Catlin and 4 by Ernest Seton, plus one photograph. Eva Emery Dye’s The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (1902) was a historical novel with Sacagawea as its heroine, with one illustration–the full-color frontispiece, a painting of “The Cession of St. Louis,” in which Lewis waits in the foreground holding the American flag.

The closest thing to a book suitable for the new audience that the centennial might stimulate was yet another printing of Biddle’s version of the journals in 1902, this time with an introduction–and the first-ever index!–by James K. Hosmer (1834-1927), a prominent author and historian. Hosmer’s introduction began with a short history of the Louisiana Purchase, with emphasis on the character of French exploration and occupation (his book, The Story of the Louisiana Purchase, also was published in 1902). He also brushed in a few more strokes in the evolving portrayal of Sacagawea as a heroine and guide who “when the trail was lost seemed to have the instinct of a wild migrating bird, and could orient herself better than it could be done with the compass.” The truth about her, which is even more astonishing than the old fantasy, awaited another few decades of study. Concluding his remarks on the post-expedition exploration, Hosmer emphasized the importance of new mechanical technology: “The great New West which the world beholds as having come to pass in the expanse traversed by Lewis and Clark may rightly be called the child of the locomotive.”

Meanwhile, Olin Wheeler’s interest in the expedition had expanded in depth and scope, inspired largely by the fact that the Northern Pacific Railway was intimately linked with the Lewis and Clark epic by the coincidence of their parallel paths in certain sections of the trail, and by the fact that he had already traveled much of it in 1899, in preparation for the article on Lewis and Clark that he published in Wonderland 1900.

Wheeler’s Objectives

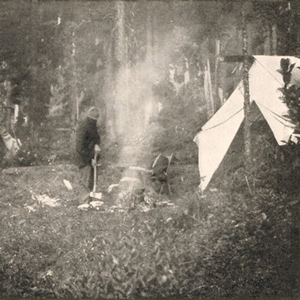

The story Wheeler wished to tell quickly grew into a project of unmanageable length, but he soon pared it down to two volumes totaling 765 pages, simply titled The Trail of Lewis and Clark.[2]The original edition (1904) of Wheeler’s volumes was published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in New York, as was the second edition (1926, with an introduction by Frederick Dellenbaugh). Both … Continue reading Its subtitle defined the general parameters: “A story of the great exploration across the Continent in 1804-06; with a description of the old trail, based upon actual travel over it, and of the changes found a century later.” The phrase “based upon actual travel over it” underscored the most important factor of all—first-hand experience. He traced the trail again in 1902, and those travels further stimulated his own sense of wonder. His personal exploration was facilitated by courtesy passes provided by other railroads whose tracks approximated certain segments of it. He returned, one reviewer observed, with “an almost boyish enthusiasm to tell all about it.”[3]Owen R. Lovejoy, “The Trail of Lewis and Clark,” Current Literature, 37:3 (September 1904), 246. In the preface he listed the five objectives that measured out his plan for studying and writing:

Objective One

“to recount the great epic story of Lewis and Clark”

For this purpose he relied chiefly on Nicholas Biddle’s 1814 paraphrase of the captains’ diaries for continuity, quoting from it extensively to lend texture and depth to the factual framework of his narrative. He also drew upon the critical edition of Biddle’s work published in 1893 by Elliott Coues (pronounced cowz), whose extensive annotations were directed largely toward the geography, ethnology, and natural history inherent in the story.

He also made frequent references to the journals of Patrick Gass, which were published in 1807, and even from Floyd’s brief journal, which had been found by Reuben Thwaites in 1893.[4]Ordway’s journal was rediscovered in 1913 and published with Lewis and Clark’s Eastern Journal in 1916, both edited by Milo Quaife of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Reuben … Continue reading

Wheeler’s major contribution to the enhancement of Lewis and Clark studies was his inclusion of numerous illustrations. The Trail of Lewis and Clark, 1804-1904 contained photographic reproductions of 8 portraits; 8 photos of important artifacts, such as Pvt. Shannon’s “housewife,” or pocket sewing kit; 15 maps; 24 manuscript documents, including copies of several pages from the original journal pages provided him by Reuben Thwaites; 24 copies of paintings by prominent American and Euro-American artists, including three by Charles M. Russell, eight by Edgar S. Paxson, two by Ralph DeCamp, and the first publication of Charles B. J. F. de Saint Mémin‘s portraits of Lewis and Clark;[5]Wheeler also reproduced one painting by Karl Bodmer, now housed at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, which does not permit its holdings to be displayed on the Web. and 117 photographs of key scenic attractions along the trail—a total of 193 images.

Objective Two

“to supplement this with such material, drawn from later explorers, as bears upon and emphasizes, or accentuates, the achievements of the original pathfinders”

In pursuit of this objective, the author drew upon a long list of journals, reports, and memoirs of explorers and other travelers who touched upon portions of the expedition’s routes. He read accounts by men who preceded Lewis and Clark into the West, some who were their contemporaries, as well as many men and women who personally advised, informed, and even accompanied Wheeler on his own retracings of the trail. The list included the Verendrye brothers and Alexander Henry the Younger, to Henry Brackenridge, John Bradbury, Warren Ferris, Stephen Long, Washington Irving, and many others. He sought out descendants of some of the principals in the expedition’s history, both Indian and white, and summarized the information they supplied.

Objective Three

“to interpret, amplify, and criticise such parts of the original narrative as the studies and explorations of the writer, one hundred years later, seemed to render advisable, thus connecting the exploration with the present time”

Possibly following Hosmer’s lead, Wheeler began with a detailed discussion of the Louisiana Purchase, setting it in the broader context provided by the intervening century of political and geographical adjustments. Throughout the rest of the book, Wheeler often drew attention to aspects of the Lewis and Clark story that had never before been discussed, such as the exact location of the rugged route across the Bitterroot Mountains. He consistently maintained the explorer’s perspective–the “inventory eye”–and tendered his own conclusions and conjectures.

Objective Four

“to show, without undue prominence, the agency of the locomotive and the steamboat in developing the vast region that Lewis and Clark made known to us”

By the end of the 19th century, more than a dozen railroads had threaded their way into the west paralleling various segments of the Lewis and Clark trail, or at least crossing it. However, it was the Northern Pacific Railway and its affiliates that not only dominated travel and commerce throughout the Northwest, but also followed some of the most interesting segments of the historic trail.

Objective Five

“to make plain that the army of tourists and travellers in the Northwest unknowingly see and visit many points and localities explored by Lewis and Clark a century ago.”

Among other features, the author had in mind the Great Falls of the Missouri, the Dearborn River, Pompeys Pillar, Bozeman Pass, the Three Forks of the Missouri, Beaverhead Rock, Travelers’ Rest, the confluence of the Clearwater and Snake Rivers, The Dalles, Cascades of the Columbia, Beacon Rock, Multnomah Falls, Coffin Rock, and Cape Disappointment. These were but a few among the many attractions to be seen in “Wonderland.”

Chapters 1–3

The Trail of Lewis and Clark 1804-1904 began with a chapter on the Louisiana Purchase, including its attendant implications and uncertainties. Wheeler also alluded to its opponents’ dire predictions, and responded with a triumphant comparison of statistics from the census of 1900 with those of 1800. “Could anything,” he concluded, “more forcibly show the clearness of Berkeley’s vision or the fulfillment of his time-honored prophecy, ‘Westward the course of Empire takes its way’?”

His second chapter, titled “Blazing the Way,” traced Thomas Jefferson‘s attempts to set in motion a search for a waterway to the Pacific, and the exploration of the valleys of the Missouri and Columbia rivers. It included a summary of the expedition’s itinerary, with Wheeler’s conclusion:

It will be seen that the Lewis and Clark trails are pretty closely related to the travelling public. It is to be hoped that, in the renaissance of Lewis and Clark and the Louisiana Purchase now possessing the country, this exploration and its trails, may be taken closer to the hearts of the people and become more and more a real part of our life.

The third chapter, devoted to the organization and personnel of the expedition, consisted of biographical sketches of some of the enlisted men, such as sergeants Floyd, Ordway, Pryor, and Gass, as well as Privates John Colter, Bratton, Shields, Shannon, and Willard, along with interpreter George Drouillard (“Drewyer”), Sacagawea, and Toussaint Charbonneau. Each was enhanced by personal communications with descendants, or documentary details from the journals of men such as fur trader Warren Ferris. The Charbonneaus’ son was never mentioned by his given name, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, in any of the journals; all Wheeler could find was a reference in the journals of fur trader Warren Ferris to his last name only. Wheeler indexed him as “Charbonneau, Toussaint, Jr.”

Biographies of Lewis and Clark opened the chapter, with extensive review of records and communications relating the Lewis’s death. Wheeler, loyal to the contemporary doctrine of his time that suicide was the selfish act of a coward, rather than a very personal tragedy, came down on the side of the murder-conspiracy argument:

I cannot . . . but believe that time and the name of Jefferson have given a fictitious weight to the theory of suicide, and that now, considering the uncertain nature of the evidence, the time has come to give Governor Lewis the full and unreserved benefit of the doubt and relieve his name and fame of the imputation heretofore resting upon it.[6]Wheeler cited three letters written in 1810 and 1811 by Gilbert Russell, who was the commanding officer of the fort at Chickasaw Bluffs, Tennessee, where Lewis changed his travel plans and set out … Continue reading

Pacific Arrival

View Toward the Columbia’s Mouth

Photographer unknown. From Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark (1904).

Astoria, Oregon, founded in 1811, is in the foreground. The three white-roofed structures on the quay at left were canneries. On the horizon at left of center, about 14 miles away, is Cape Disappointment, the northern limit of the Columbia’s mouth. On the middle distance, some 6 miles across the estuary, is Chinook Point, where the men camped on 15 November 1806. The high land toward the right side of the photo may be part of the “opening of the Ocean” they saw from another 15 or 20 miles up the river.

Biddle had described the moment on 7 November 1805 when the captains and their men realized they were approaching their destination: “We had not gone far . . . when the fog cleared off, and we enjoyed the delightful prospect of the ocean; that ocean, the object of all our labours, the reward of all our anxieties. This cheering view exhilarated the spirits of the party, who were still more delighted on hearing the distant roar of the breakers.” It was basically consistent with the original, but it lacked something to seize the heart. Wheeler consulted the original codex, and found the phrase that struck him then, as so many others have been since, with the triumphant resonance and ring of discovery: “Ocian in view! O! the joy.”

Wheeler was skeptical. The explorers were probably more than twenty miles up the Columbia, while to a person sitting in a dugout canoe the horizon appears no more than three miles distant. “It is hardly possible that the party then really saw the ocean,” he wrote, continuing:

During one of my trips on the river, with this very point in mind, I was particular to study the situation from the pilot-house of a steamer. Being extremely uncertain about it, I laid the case before the Captain, an intelligent and experienced river man, and he replied that the “octian” could not be seen from there, but that during a storm the breakers could be heard. No storm, however, is noted by Lewis and Clark at this point.

That famous exclamation—a figure of speech, perhaps—was of course a characteristic Clarkian misfire (he was a much better marksman with a rifle than with a pen), but he took aim again in his courses and distances for the day, and hit the mark squarely between the dark low contours of the coastal ranges that bend down to Columbia’s estuary on both sides: “We are in view of the opening of the Ocian, which Creates great joy.” Those plain facts notwithstanding, some 21st-century readers are still fond of debating the question, “Could they really see the ocean?”

Early on in his own studies of the original journals, copies of which Thwaites had shared with him, Wheeler began to get an inkling that Clark’s diaries, “with their lack of punctuation and their orthographic peculiarities, one is tempted to believe at times that the Captain had in mind when writing, a vague idea of a system of short-longhand, to be elaborated later on.” Indeed, they were often as Wheeler suspected, merely memos for a work in progress.[7]Wheeler quoted Clark’s description of a tragic prairie fire that swept past their camp on the evening of 29 October 1804. In addition to his usual phonetic spelling of a regional pronunciation … Continue reading One suspects that Wheeler would have strongly disapproved of many 21st-century readers’ preference for reading the journals in their original form.

In contrast, he observed that Lewis’s handwriting showed a distinct type of personality. His journals, he noticed, “are in a fine, regular, symmetric handwriting, almost as clear and legible as engraving, and evince the conscientiousness of the man in his work.”[8]Graphology, or handwriting analysis, was a relatively new science in Wheeler’s day.

Digressions

Brief digressions from the successive events on the expedition served Wheeler’s intention of describing the changes that had occurred during the century just past. He discussed some of the forts built by fur traders between 1808 and 1850, including Forts Benton, Berthold, Buford, Cass, Clark, Manuel, Pierre, Sarpy, and Union.

Clark explained the importance of blue beads to the Nez Perces: They “may be justly compared to gold and Silver among civilized nations.” Lewis and Clark knew the value of gold and silver, but precious metals were not high on their basic list of minerals to watch for. However, when Wheeler was on the Jefferson River, and happened to be in the neighborhood, he brought up the gold discoveries of 1862 on Willard’s Creek. In the same vein, talk of gold strikes evoked legends of road agents, corrupt sheriffs, and righteous vigilantes—the blacker Romance of the mountain West.

Similarly, at the turn of the century Butte and Anaconda, then at the peak of their worldwide fame arising from their productivity in gold, silver, and especially copper, summoned several pages of historical commentary and some amazing statistics from Wheeler, even though they were many miles from the nearest part of the Lewis and Clark trail. That brought up the subject of Great Falls, and the dams on the Missouri River there, generating electricity that was transmitted to Butte and Anaconda to operate machinery and light the mills and mines 24 hours a day.

In his summary of Clark’s exploration of the Yellowstone River, however, Wheeler digressed into a “what-if” argument that gave him the chance to make a point for conservation, a popular movement that had begun before 1850 and reached it first triumph in 1872 with the establishment of Yellowstone National Park:[9]The generation of Lewis and Clark had lived by the conviction that wild nature was meant to be “improved,” that is, civilized and used. in 1851, Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) responded … Continue reading

It is a matter for congratulation . . . that Clark did not learn of that wonderful land, and that he did not discover Yellowstone Park. Had either of these things happened we would probably have no park, as such, to-day. A hundred, or even fifty years ago, we would not have appreciated the possibilities and advantages of making such a spot into a National Park, and had its weird possessions then been made known, the region would have been despoiled . . . of its pristine wonders and grandeur

Visualizing Clark at Pompeys Pillar on July 25, 1806, led Wheeler to reflect on the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which took place “[j]ust seventy years and one month” afterward, and to think of the army forts that were scattered through eastern Montana to meet “the flickerings of a declining and futile opposition to an evolution that was rolling on with the certain and remorseless advance of a Juggernaut.”

Such digressions as these, and many more, added up to a tourist’s guide to the Lewis and Clark trail gauged to the interests and expectations of travelers on a high-speed, comfortable, and affordable mode of travel, and to heighten the fascination and historical appeal of the Romance of the New Northwest.

Nonetheless, Wheeler was proud to point out that the Northern Pacific Railway had built a branch line from Bozeman to the north entrance to the park in the mid-1880s.

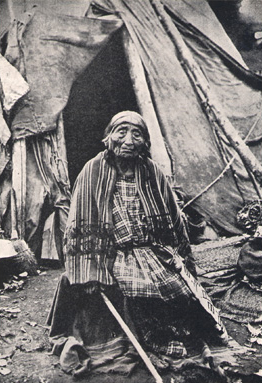

Attitudes Towards Indians

After Wheeler’s feature article on Lewis and Clark appeared in Wonderland 1900, a series of personal connections beginning with Eva Emery Dye, author of the fictionalized biography of William Clark, his brother George Rogers Clark, and “Sacajawea,” titled The Conquest, led him to an interview with this Cayuse Indian woman named Pe-tów-ya. She remembered as a child meeting the two captains as well as York. Pe-tów-ya died in 1902 at the age of 111 years.

His attitudes toward Indians was similarly ambivalent. On the one hand, he presented verbal and visual evidence that some tribes were becoming acculturated. On the other, he referred to the rest as savages, a word that had by then dropped to the level of a pejorative. Still, he emphatically deplored the treatment Indian people had received since the time of the expedition. Lewis and Clark’s:

almost uniformly kind reception by, and treatment of, the Indians, and their absoloute and utter dependence upon them, time after time, for food with which to save themselves from starvation, and for animals and canoes with which to continue their journey, furnishes the most caustic criticism upon the Government’s subsequent treatment of the red man.

Indeed, Wheeler had already described Clark’s success as superintendent of Indian affairs for Louisiana Territory:

Had the Government, in its subsequent dealings with the Indians, taken several leaves from Clark’s experience and copied them, the vast amount of treasure expended, the lives sacrificed, and trouble of all sorts endured in the recurring Indian wars, might have been saved.

Reading Wheeler Today

Wheeler had called the United States’ westward expansion inevitable, and he credited its northern-tier component to the success of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Its “relation . . . to the location of the Northwestern boundary line is a very intimate one,” he wrote. “It is altogether likely,” he continued, “that Washington and the Puget Sound country might have been lost to the United States, had their contentions been based upon the discoveries of Gray alone.”

To Wheeler, the railroads that followed most of their trail also had transformed the West, opening the way for trade relations with Asia that have continued to expand in scope and volume, just as Wheeler predicted would happen:

The Lewis and Clark expedition was the precursor of the railway which, in the last half-century, has revolutionized and transformed the West and Northwest, and the present active expansion of our Oriental commerce, rendered possible by the railway, emphasizes the importance of the achievements of the explorers . . . and what, under a wise fostering, the future has in store, no man may prophesy.

Wheeler’s Trail of Lewis and Clark is in many ways difficult to appreciate today. He was prone to blatant racism, thinly veiled sexism, and unabashed chauvinism. He was wholeheartedly committed to the interlocking values of Progress and Manifest Destiny, and a Panglossian view of his nation and its place in world of the early 1900s. On the other hand, his book holds at least three features that make it exceptionally valuable to the serious student of the expedition and its history. First, his numerous photographs that provide us with candid glimpses of “the face of the land” a century after Lewis and Clark saw it. Second, his inclusion of quotations representing the perspectives of subsequent explorers and other travelers, which lend broader and longer dimensions to the original story. Finally, his energetic and disciplined inquiry into the details of people and places make it a benchmark for historical understanding.

The Rest of the Story

The Northern Pacific Railway had identified two new attractions within its Wonderland—a centennial commemoration of the historic Lewis and Clark expedition, plus extensive segments of the original trail within sight of its rails.

One of Wheeler’s most successful efforts to amplify any part of Lewis and Clark’s route was his exploration of the Lolo Trail. For that he relied heavily on Elliott Coues’ 1893 annotations to the expedition’s narrative.

Traveling through the Marias River country with anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, Wheeler met Wolf Calf, one of the Indian survivors of Lewis’s encounter with the Blackfeet.

In 1902, Wheeler followed the Northern Pacific’s course over Bozeman Pass and the Yellowstone River promoting both the railroad and the Lewis and Clark Centennial.

At The Dalles in 1902, a hospitable local citizen helped Wheeler make his way to the brink of the long narrow channel and chasm through which Lewis and Clark took their canoes, where he “overlooked the swirling waters as they boiled and raged.”

Notes

| ↑1 | For an account of Thwaites’s tribulations in publishing the first complete edition of the journals, see Paul Russell Cutright, A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1976), 104-127. Coues’s work is discussed in ibid., 73-103. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The original edition (1904) of Wheeler’s volumes was published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in New York, as was the second edition (1926, with an introduction by Frederick Dellenbaugh). Both have been out of print for many years. It was reprinted in 1976 by AMS Press, and in 2002 by DIS Digital Reproductions. The originals of all of Wheeler’s illustrations apparently have been lost, except for a few photos at the Newberry Library in Chicago. |

| ↑3 | Owen R. Lovejoy, “The Trail of Lewis and Clark,” Current Literature, 37:3 (September 1904), 246. |

| ↑4 | Ordway’s journal was rediscovered in 1913 and published with Lewis and Clark’s Eastern Journal in 1916, both edited by Milo Quaife of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Reuben Thwaites acquired Whitehouse’s journal in 1903, too late to be of use to Wheeler. |

| ↑5 | Wheeler also reproduced one painting by Karl Bodmer, now housed at the Joslyn Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, which does not permit its holdings to be displayed on the Web. |

| ↑6 | Wheeler cited three letters written in 1810 and 1811 by Gilbert Russell, who was the commanding officer of the fort at Chickasaw Bluffs, Tennessee, where Lewis changed his travel plans and set out overland toward Washington City. One of those letters, in which Russell detailed the circumstances of Lewis’s self-inflicted death as he understood them, is reprinted in Donald Jackson’s Letters, 2:573-575. Further, Jackson cited the study of Lewis’s death by Dawson A. Phelps, “The tragic death of Meriwether Lewis,” William and Mary Quarterly, ser. 3, 13 (July 1956), 305-18, as the most convincing argument supporting the verdict of suicide. |

| ↑7 | Wheeler quoted Clark’s description of a tragic prairie fire that swept past their camp on the evening of 29 October 1804. In addition to his usual phonetic spelling of a regional pronunciation of “tremenjus,” it produced a rippling little tongue-twister of a noun: The fire “went with great rapitidity [emphasis added] and looked Tremendious.” It seems Wheeler didn’t even crack a smile. |

| ↑8 | Graphology, or handwriting analysis, was a relatively new science in Wheeler’s day. |

| ↑9 | The generation of Lewis and Clark had lived by the conviction that wild nature was meant to be “improved,” that is, civilized and used. in 1851, Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) responded that “In wildness is the preservation of the world.” His Walden; or, Life in the Woods (1854) remains the basic scripture for the conservation and environmentalism movements. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.