Hunting had long been a gentleman’s sport. The chase has been governed by laws promulgated by kings and queens.

The pursuing of four-footed beasts, as badgers, deer,

does, roebucks, foxes, hares, &c., properly termed

hunting, is a noble exercise, serving not only to

recreate the mind, but to strengthen the limbs,

whet the stomach, and chear up the spirits.

A Noble Exercise

Figure 1

Charles I, King of England, at the Hunt (1635)

Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641)

Oil on canvas. Louvre, Paris, France.

In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century portraiture, huntsmen were often depicted in fashionable attire such as this. The association of hunting with power and privilege, and with the attendant opulence and splendor, was recorded by ancient Greek writers such as Virgil, in his Aeneid.

Beginning in the Late Middle Ages until the end of the nineteenth century the chase,[1]Both captains, but most often Lewis, used the term chase figuratively as a synonym for “hunting,” either afoot or on horseback, by men working singly or in groups. For examples see Clark, … Continue reading that is, the pastime of pursuing wild animals for sport with dogs whose natural urge to hunt and kill was deliberately honed, was governed by laws promulgated by kings and queens. In the middle of the eighteenth century, for example, British law clearly defined who could take part: “The persons qualified to keep guns, dogs, &c. are those who have a free warren, or £100 [pounds Sterling] a year by inheritance or for life, or a lease for ninety-nine years of £150 per annum, also the eldest sons of esquires.” A warren was a parcel of fenced land used for breeding game. A squire, who ranked next below a knight, was a gentleman, a man of “gentle birth” or distinguished ancestry who was entitled to inherit land and bear arms. By the opening of the nineteenth century the word also had come to serve as a respectful form of address. Noah Webster, in his first dictionary (1806) defined it as “a term of complaisance,” and complaisance as “civility, an obliging behavior.”[2]Lewis and Clark often wrote of both familiar and unfamiliar guests, especially those evidently in positions to extend favors, assistance or information, as “gentlemen.” After they left … Continue reading Hunting was a noble exercise, a gentleman’s sport.

Landowners employed wardens who were responsible not only for “keeping and preserving the game,” but also were authorized by law to “seize guns, dogs or nets used by unqualified persons for destroying the game.” It was a felony “for persons to appear armed and disguised in a forest or park, and hunt or kill the deer.” Woodcutting or otherwise damaging a landlord’s trees was punishable by imprisonment for three months, with the culprit “whipt once a month.”

Hunting Dogs

Figure 2

Greyhound, c. 1790

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828)

Wood engraving, 4.4 x 7.3 cm. The Edmonton Art Gallery, EAG 90.39.126.

“A hunting dog that deserves the first place, by reason of his swiftness, strength and sagacity in pursuing his game; for such is the nature of this dog, that he is speedy and quick of foot to follow, fierce and strong to overcome, yet silent, coming upon his prey unawares.”[3]The Sportsman’s Dictionary, or,The Gentlemen’s Companion for Town and Country, 4th ed., (London:G.G. J. and J. Robinson, 1800). A revival of Americans’ interest in coursing began … Continue reading

Figure 3

Beagle, c. 1790

Thomas Bewick

Wood engraving, 4.6 x 8 cm. The Edmonton Art Gallery, EAG 90.39.126.

“Of those Dogs that are kept for the business of the chase in this country [England], the Beagle is the smallest, and is only used in hunting the Hare. Although far inferior in point of speed to that animal, it follows by the exquisiteness of its scent, and traces her footsteps through all the various windings with great exactness and perseverance. Its tones are soft and musical, and add greatly to the pleasures of the chase.”[4]Thomas Bewick, A General History of Quadrupeds (London, 1790), 299. See also on this site, Domestic Dogs.

Four-footed animals such as hares or deer were pursued, or “coursed,” by carefully trained packs of scenthounds such as beagles or foxhounds, or by sighthounds such as greyhounds, while huntsmen on horseback followed and looked on. One of the game-keeper’s regular tasks was to keep the lower branches of his landlord’s trees trimmed to enable hunstmen to ride swiftly and safely among them.

Upland birds such as grouse and partridges usually were shot by hunters on foot, with or without dogs, using fowling pieces resembling the modern shotgun. (William Clark recorded on 16 November 1805 that their “fowlers killed . . . 1 Crane & 2 ducks.”) Some birds were instead captured with nets, traps or snares. This sport was called fowling.[5]A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 2nd ed., 8 vols. (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1764). There is evidence to indicate that the expedition carried a set of this reference work, which … Continue reading The ancient sport of hawking, which also was traditionally symbolic of noble birth, privilege and leisure, employed trained raptors such as hawks, ospreys, falcons, or kestrels to capture small mammals or fish; today it is more commonly called falconry.

Hunting Horns

In his right hand the hunter grasps his horn, a pocket-sized instrument made of brass, without keys but with a small cupped mouthpiece that enabled a person to blow short triadic tunes or “calls” by changing the embouchure, or shape and pressure of his lips.

Hunting seasons were defined mainly in terms of Christian feasts. The season for hart-and buck-hunting,[6]In England a hart is a male, or stag, of the red deer; a buck is a male fallow deer. for example,

begins a fortnight after midsummer [5 July], and lasts till holy-rood-day [14 September]; that for the hind [female of the red deer] and doe, begins on holy-rood-day, and lasts till candlemas [Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Feb. 2, midway between winter solstice and spring equinox]; that for fox-hunting begins at Christmas, and holds till lady-day [Feast of the Annunciation, March 25]; that for roe-hunting begins at michaelmas [Feast of St. Michael and All Angels, 29 September], and ends at Christmas; hare hunting commences at michaelmas, and lasts till the end of February; and where the wolf and boar are hunted, the season for each begins at Christmas, the first ending at lady-day, and the latter at the purification.

Descriptions of the elaborately detailed ceremonial formalities, the ritual brutalites, and the arcane jargon of the royal pastime are found in contemporary sportsman’s guides, dictionaries and encyclopedias, such as George Turberville’s The Noble Art of Venerie or Hunting (London, 1611). “View halloo” was the signal that the prey was in sight of the hunters who were in the lead. The view halloo for a hare was, “gone away”; “tally ho” was the cry for a fox. The expression “get in” meant to be first to reach the prey after it was brought down by the dogs. To “paunch” was to eviscerate or cut open. The paunch is the first stomach of a ruminant quadruped, from which food is regurgitated for cud-chewing. A “recheat” was a horn signal to call the hounds together. The Old French verb rachater meant “to reassemble, rally.”

In order to facilitate the chace, the game-keeper commonly selects a fat buck out of the herd, which he shoots in order to maim him, and then he is run down by the hounds. . . . When he is run down, every one strives to get in to prevent his being torn by the hounds . . . . He that first gets in, cries hoo-up, to give notice that he [the prey] is down and blows a death. When the company are all come in they paunch him and reward the hounds; and generally the chief person of quality amongst them takes say, that is, cuts his belly open, to see how fat he is. When this is done, every one has a chop at his neck, and the head being cut off is shewed to the hounds to encourage them to run only at male deer. . . . and to teach them to bite only at the head: then the company all standing in a ring, one blows [on his horn] a single death, which being done all blow a double recheat, and so conclude the chace with a general halloo of hoo-up, and depart the field to their several homes, or to the place of meeting; and the huntsman, or some other, hath the deer cast cross the buttocks of his horse, and so carries him home.[7]Owen’s Dictionary, s.v. “Hunting.” Evidently quoted from The Sportsman’s Dictionary, or, The Gentlemen’s Companion for Town and Country, 4th ed., (London:G.G. J. and J. … Continue reading

The success of a hunt depended in part upon the weather, too. When the atmosphere was very dry, or when a sharp northerly breeze prevailed,

the scent or exhalation from the hunted animal is rarefied and dissipated, and becomes consequently impossible to be traced and followed up by the dogs. When, on the other hand, the air is moist, but without the presence of actual rain, and a gentle gale blows from the south of west, then the scent clings to the adjoining soil and vegetation; and a more favourable condition still is, when it is suspended in the air at a certain height from the earth, and the dogs are enabled to follow it breast high, at full speed, without putting their heads to the ground.[8]Robert Chambers (1802-1871), ed.,The Book of Days, a Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers, 1832), 489. This article on fox … Continue reading

Hunting Songs

This celebrated Scottish hunting song, flowing at a lively lope of iambic feet, captures a sentimental early-morning scene (see also Fig 5):

D’ye ken John Peel with his coat so gay?

D’ye ken John Peel at the break of day?

D’ye ken John Peel when he’s far, far away?

With his hounds and his horn in the morning?‘Twas the sound of his horn brought me from my bed,

And the cry of his hounds which he oftimes led,

For his “view halloo” would waken the dead,

Or the fox from his lair in the morning.Yes, I ken John Peel and Ruby too!

Ranter and Ringwood, Bellman and True!

From a find to a check, from a check to a view,

From a view to a death in the morning![9]This song, attributed to John Woodcock Graves, dates from 1820; the tune to which it most often has been sung was based on a Scottish dance tune called “Bonnie Annie,” which can be heard … Continue reading

To be sure, “riding to the hounds” required good horsmanship and, considering the occasional challenge to jump fences and low walls, a considerable measure of courage and physical stamina as well. But Thomas Jefferson‘s expedition could have had no use for hunters of this ilk—for devotees of a mere gentleman’s “pastime” in which it was dogs that did the hunting, and dogs that drew the blood. And the rest was all for show. No more could be expected of gentlemen’s sons, either.

Riding to the hounds reached its lowest level of respectability in the United States before the middle of the nineteenth century. A revival of interest in the ancient sport during the 1880s and 90s was followed by renewed efforts to ban hunting with hounds. One result that eventually emerged in the U.S. was the training of dogs to run the fox “to ground,” that is, until it takes cover in one of its dens. At that point the dogs are trained merely to “mark” the spot by baying at the hole until the hunters call them off. Foxhunting was finally prohibited by law in England and Wales early in 2005, and soon thereafter in Scotland. It is still legal in Virginia, however, and in various other places in the U.S. and Canada. Also, there are two uniquely American forms of the sport. In several western states the hunting of coyotes—being considered “vermin” as foxes and hares once were—with dogs is legal, as is the southern tradition of hunting racoons with coonhounds.[10]In 1877 the Montana Territorial Legislature declared it unlawful to hunt or chase game animals with dogs. One alternative to the killing of prey, introduced in the U.S. about 1900, is the drag hunt, in which a dragsman creates a scent trail over a random course by dragging a bag containing animal meat and an herb such as aniseed. Thus the social appeal of the traditional chase is retained, while the barbarisms of the old blood-sport are eliminated.

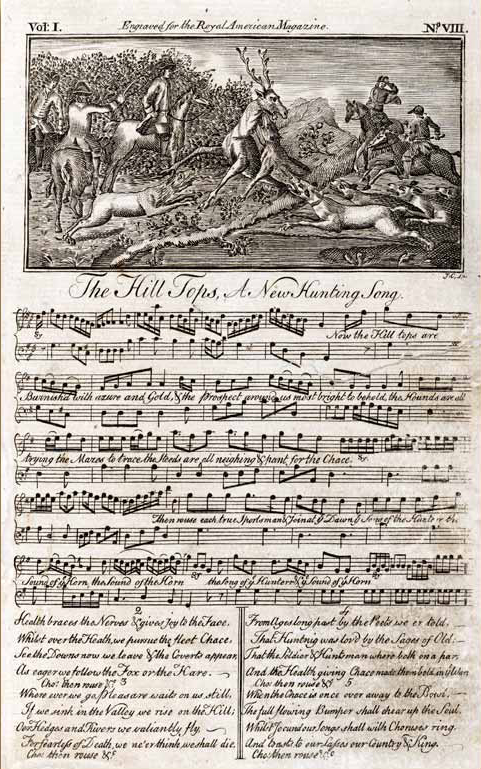

Hunting songs were part of European popular music from the seventeenth through the early nineteenth century. The word song denoted a poem intended for singing; the music was called the tune or air. A reader was welcome to sing any song to any air he knew that had a metrical rhyme-scheme matching that of the song. A half-dozen songs were published in the Royal American Magazine, or Universal Repository of Instruction and Amusement during its total life of fifteen consecutive monthly issues beginning in January 1774. This is the only hunting song among them, and the only one that appeared with its own air. The author and composer are anonymous, but the identity of either would have been unimportant in those days. Popular songs were common property.

But why would a song about a British gentleman’s pastime be published in this magazine which, despite the adjective in its title, was anything but a Royalist tool. Propaganda for the patriot cause was a prominent theme among its contents, calculated to antagonize the British Government and give aid and comfort to the rebels.[11]Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 5 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938-68), 1:84. Among its twenty-two copper-plate engravings were some political cartoons by the … Continue reading The Royal American Magazine often included satires or burlesques; perhaps both its name and “The Hill Tops” belong in that category.

Among the leading New England pioneers of early American music was Timothy Swan (1758-1842), of Worcester, Massachusetts, by profession a hatter and by calling a talented poet and tunesmith who wrote hymns, psalm-tunes, and fuguing tunes for congregational use, plus a few secular pieces. His first collection, printed in Suffield, Connecticut in 1800, was The Songster’s Assistant, containing a variety of the best songs, most of the music never before published. It contained two hunting songs for treble and bass duet, which are unsigned but have been attributed to Swan himself. One of them began excitedly,

The morning is charming, all nature is gay,

Away, my brave boys, to your horses away;

For the prime of our pleasure is coursing the hare,

We have not so much as a moment to spare.Hark, the lively-toned horn, how melodious it sounds

To the musical song of the merry-mouthed hounds.

Once again the question arises: Why, in the very cradle of the newborn nation, did a former enlistee in the Continental Army, a member of the Brotherhood of Masons, and a loyal Federalist, write, compose, and publish two Tory songs? Perhaps it was merely a gesture that he figured might sell some of his books to a few sentimental American “gentlemen” who would enjoy reliving the old days vicariously.

A Gentleman’s Son

Figure 6

The Hunters’ Return, 1845

Thomas Cole

Oil on canvas, 40-1/8 x 60-1/2 inches. Amon Carter Museum, Fort Worth, Texas.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848) was an English-born artist who immigrated to America as an engraver and became the de facto founder of the Hudson River School of landscape painters. His most admired works were his portrayals of the American wilderness on the brink of ruin by civilization—by the steamboat and the steam locomotive, which he could observe first-hand in the forests near Catskill, New York, where he lived during the 1830s.

The Hunter’s Return was especially popular in its day, owing partly to its timing, and partly to its inherent ironies. It was, on the one hand, an escapist celebration of the pristine forest as a sanctuary of republican family values, a “retreat to an earlier era or more primitive stage in human progress, when each man was in greater control of his own life and his own destiny.”[12]Ellwood C. Parry, III, “Thomas Cole’s “The Hunter’s Return,” American Art Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Summer, 1985), 2. Those sentiments are melded with the artist’s favorite theme of return and reunion.

The scene is set on the bank of a waterfall-fed lake among the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The porch of the neatly built log cabin is graced with vines that have climbed to the cabin’s ridgepole; an overhang of the roof shelters the back door. A small window under the eaves admits light into the garrett where some of the family members sleep. At the opposite end of the cabin is a carefully crafted chimney, adjacent to a clean livestock lean-to. Stumps and prostrate limbs and trunks indicate that the process of clearing more land is in progress. Already there is space enough for a dooryard garden of cabbage and corn. The parallel ruts of wagon wheels reveal that this home in the wild is accessible not merely by a trail but by a road, which has necessitated the building of a corduroy bridge across the stream. The hunter and his eldest son approach with a freshly killed buck suspended on a pole across their shoulders. A young boy has rushed out to herald their arrival, with the privilege of carrying his father’s rifle and shot bag. The hunter’s dog has raced ahead into the arms of a little girl. The younger hunter’s wife holds up her baby, who is squealing with delight. Grandmother stands in the doorway, arms outstretched. The scene is bathed in advancing twilight that accentuates the early autumn colors.

Within the frame of this picture, its balanced, idyllic lifestyle is perfectly complete. All of its elements—its actions, sounds, aromas, and colors—fold happily into the safe refuge of a cabin that is remote from the disorder, noise and stench of a city. The conservative generation of Jefferson, Lewis and Clark is past, and here, in the theatre of Jacksonian democracy, the hunter becomes a new role model. He is the rugged individualist at the heart of Jacksonian Democracy, with scenery designed by Thomas Cole.

Although nowhere is it said that he did so, there is ample reason to imagine that Meriwether Lewis, himself a scion of the Virginia gentry, could have “followed the hounds,” for his ancestors had more than likely brought with them the lore of the chase. The American lineage of his father, William, with its antecedents in Wales, was established by General Robert Lewis, who arrived in Virginia in 1635 with patents on 33,333-1/3 acres given him by King Charles the First (Fig. 1). Eventually Robert divided his land into a number of smaller plantations which he distributed to various members of the extended Lewis family. Among his more prominent descendants was Major John Lewis, who served as a member of the King’s Council from 1685 until 1700. The family of Meriwether’s mother, Lucy Meriwether—originally spelled Merryweather, meaning “happy in all kinds of weather”—on 3-4 July 1806, traced its Welsh lineage back as far as 1066. Three Meriwether brothers had settled in Virginia in the 1650s on 5,250 acres of land granted to them by King Charles II in repayment of a personal loan. As wealth begets wealth, by 1730 the Meriwethers owned nearly 18,000 acres near Charlottesville, Virginia, and thousands of acres elsewhere, plus sufficient numbers of slaves to cultivate the land.[13]Rochonne Abrams, “The Colonial Childhood of Meriwether Lewis,” The Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, Vol. 34, No. 4, Part 1 (July 1978), 218-19.

William Clark’s status and ancestry were nearly parallel with those of the Lewises and the Meriwethers. John Clark, from Kent, in England, settled in Virginia on the James River in the late seventeenth century, and his mother’s folks emigrated from Scotland at about the same time. But there were differences later. “Attendance at weddings, funerals, public proceedings, barbecues, horse races, and cockfights introduced the Clark sons to the rituals of planter society and prepared them for their roles as proper gentlemen.”[14]William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 4.

Indeed, there were plenty of gentlemen planters like the Lewises, the Meriwethers, the Clarks and the Rogerses whose families had dwelled on the Piedmont plateau of Virginia and the Carolinas for several generations. Men to whom “riding to the hounds” or “field coursing” was both appealing and convenient given that most of that part of the country consisted of adjoining plantations owned by persons of like mind and status, and often related either by blood or by marriage. Under those circumstances there was little need to worry about offending small farmer-neighbors by riding through their grain fields or barnyards. George Washington, who imported his scarlet riding frocks from England, was passionately devoted to the sport. Alexander Hamilton, and even Thomas Jefferson in his youth, took part in it too. But the appeal of the “sport” was evident even in the North. The Gloucester Fox Hunting Club of Philadelphia, which was organized in 1766, quickly drew a membership of 125 devotees. The club boasted a hounds-keeper who, reflecting American aristocrats’ own slant on the sport, was a slave called Natty, his name suggesting that the members must have seen to it that he was stylishly outfitted in British hounds-keepers’ livery.[15]Daniel Justin Herman, Hunting and the American Imagination (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 68-74.

A Licentious Idle Life

Opposition to sport hunting began early in the Renaissance with screeds such as In Praise of Folly (1511), in which the early humanist Desiderius Erasmus described the aristocratic huntsman as a foolish, wasteful butcher, a “gentleman, who shall throw down his hat, fall devoutly on his knees, and drawing out a slashing hanger, for the common knife is not good enough, after several ceremonies shall dissect all the parts as artificially as the best skilled anatomist, while all that stand round shall look very intently. . . . And he that can but dip his finger, and taste of the blood, shall think his own bettered by it.”[16]Desiderius Erasmus (d. 1536) In Praise of Folly (1511; London, 1887), 87.

More than two centuries later the same sentiment sprang up among the very grassroots of American life. Because most immigrants came from northern Europe’s “meane” class, they brought no experience and little direct knowledge of the ancient traditions of “the hunt,” so it was easier to criticize them. Moreover, the Land Ordinance of 1785, initially drafted by Thomas Jefferson as part of a plan to sell frontier lands to settlers in order to cover war debts, had an additional benefit. It would serve to refine the structure of frontier society and draw it toward the blessings of civilization.[17]Peter S. Onuf, “Liberty, Development, and Union: Visions of the West in the 1780s.” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 43, no. 2 (April 1986): 188, 189, 195. Behind the ordinance, implicitly at least, was the concept of four successive stages of human subsistence that human societies had to go through to attain that elevated status. Emerging in the mid-eighteenth century from the writings of Adam Smith, Thomas Hobbes, and John Locke, the four-stage theory began at the lowest subsistence level with hunting and gathering—as Indians and other preliterate peoples did (never mind that most tribes were at least partly agricultural.) In the second, or pastoral stage, society at large maintained a simple Arcadian existence, tending flocks of certain domesticated animals.

The third stage, which was the foundation of civilization, was agricultural. As Daniel Herman has summarized it, this stage in America rested largely upon a dedicated population of husbandmen who were mostly “small producers of middling rank.”

With their Protestant, evangelical emphasis on work and calling, they were not so willing to accept the country squire, or his American equivalent, as the natural leader of republican society; Americans conceived of the yeoman freeholder as the backbone of republicanism. Small farmers were the self-sufficient, liberty-loving, disinterested men capable of guaranteeing good government and virtue.[18]Herman, Hunting, 41-45.

Or, as Jefferson explained it to François Barbé-Marbois, the secretary of the French legation to the United States: “Those who labour in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people, whose breasts he has made his peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which he keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth.”[19]Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), Query XIX. Only to the extent that farmers must employ the gun to combat pests and predators was hunting morally acceptable.

To thoughtful observers, then, the very plenitude of wild game in the American Wests, both Old and New, was pernicious because it could draw men away from their farms toward a lower standard of living. St. John de Crèvecœur, a minor French nobleman who settled in New Jersey in 1765, warned of the inevitable downfall of all American farmers who let hunting override the virtues of agriculture:

By living in or near the woods, their actions are regulated by the wildness of the neighbourhood. The deer often come to eat their grain, the wolves to destroy their sheep, the bears to kill their hogs, the foxes to catch their poultry. This surrounding hostility immediately puts the gun into their hands; they watch these animals, they kill some; and thus by defending their property, they soon become professed hunters; this is the progress; once hunters, farewell to the plough. The chase renders them ferocious, gloomy, and unsociable. . . . That new mode of life brings along with it a new set of manners, which I cannot easily describe. These new manners being grafted on the old stock, produce a strange sort of lawless profligacy, the impressions of which are indelible. The manners of the Indian natives are respectable, compared with this European medley. Their wives and children live in sloth and inactivity; and having no proper pursuits, you may judge what education the latter receive. Their tender minds have nothing else to contemplate but the example of their parents; like them they grow up a mongrel breed, half civilised, half savage. . . . Thus our bad people are those who are half cultivators and half hunters; and the worst of them are those who have degenerated altogether into the hunting state.

“Hunting is but a licentious idle life,” Crèvecœur concluded, “and if it does not always pervert good dispositions; yet, when it is united with bad luck, it leads to want: want stimulates that propensity to rapacity and injustice, too natural to needy men, which is the fatal gradation.”[20]Hector St. John de Crèvecœur (1735-1813) Letters from an American Farmer (London, 1782; Philadelphia, 1793; New editiion with introduction and notes by Warren Barton Blake; New York: E. P. Dutton … Continue reading

The message was unmistakable. The farmer’s life was affirmative, hopeful, and progressive. The hunter’s life was negative, cynical, and regressive. Downright unpatriotic.

Role Model

As to civilization’s fourth and final stage in the Course of Empire, it is sufficient to remember Jefferson’s response to Meriwether Lewis’s bellicose impulse to hasten the Indian peoples’ progress toward it: “Commerce is the great engine by which we are to coerce them & not war,” the President insisted. The experience of the ages had not only proved the truth of the four-stages theory, but also testified to its ultimate risks. Commercialism was fraught with its own dangers, of course, especially the threat of materialism and greed, but those remained to plague future generations. For the time being, the contest was between husbandry and hunting.

Meanwhile, what Lewis and Clark really needed—though they didn’t say it in so many words—was a hunter of professional caliber who was grounded in agrarian, republican citizenship. A genuinely natural man. A bold, honest individualist. A hunter-hero. A man like Daniel Boone.

Notes

| ↑1 | Both captains, but most often Lewis, used the term chase figuratively as a synonym for “hunting,” either afoot or on horseback, by men working singly or in groups. For examples see Clark, 7 December 1804; Lewis, 8 August 1805; Lewis, 23 August 1805; Lewis, 5 January 1806 and 8 June 1806. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lewis and Clark often wrote of both familiar and unfamiliar guests, especially those evidently in positions to extend favors, assistance or information, as “gentlemen.” After they left Fort Mandan in the spring of 1805, Lewis sometimes applied the word sarcastically to grizzly bears as well as potentially hostile Indians. |

| ↑3 | The Sportsman’s Dictionary, or,The Gentlemen’s Companion for Town and Country, 4th ed., (London:G.G. J. and J. Robinson, 1800). A revival of Americans’ interest in coursing began shortly after the middle of the nineteenth century and reached its peak among the princes of America’s opulent Gilded Age during the 1870s, 80s, and 90s. President Theodore Roosevelt wrote in 1893 that “for half a century the army officers posted in the far West have occasionally had greyhounds with them, using the dogs to course.” Theodore Roosevelt, Hunting the Grisly and Other Sketches (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1893). |

| ↑4 | Thomas Bewick, A General History of Quadrupeds (London, 1790), 299. See also on this site, Domestic Dogs. |

| ↑5 | A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences, 2nd ed., 8 vols. (London: Printed for W. Owen, 1764). There is evidence to indicate that the expedition carried a set of this reference work, which was familiarly known as Owen’s Dictionary. |

| ↑6 | In England a hart is a male, or stag, of the red deer; a buck is a male fallow deer. |

| ↑7 | Owen’s Dictionary, s.v. “Hunting.” Evidently quoted from The Sportsman’s Dictionary, or, The Gentlemen’s Companion for Town and Country, 4th ed., (London:G.G. J. and J. Robinson, 1800), s.v. “Buck Hunting.” |

| ↑8 | Robert Chambers (1802-1871), ed.,The Book of Days, a Miscellany of Popular Antiquities in Connection with the Calendar, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: W. & R. Chambers, 1832), 489. This article on fox hunting was reprinted in numerous American miscellanies during the nineteenth century. |

| ↑9 | This song, attributed to John Woodcock Graves, dates from 1820; the tune to which it most often has been sung was based on a Scottish dance tune called “Bonnie Annie,” which can be heard at various sites on the Web. The title of a truly engrossing study of the hunt is borrowed from the last line of this innocent little song: Matt Cartmill, A View to a Death in the Morning: Hunting and Nature through History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993). |

| ↑10 | In 1877 the Montana Territorial Legislature declared it unlawful to hunt or chase game animals with dogs. |

| ↑11 | Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 5 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938-68), 1:84. Among its twenty-two copper-plate engravings were some political cartoons by the legendary patriot Paul Revere. |

| ↑12 | Ellwood C. Parry, III, “Thomas Cole’s “The Hunter’s Return,” American Art Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Summer, 1985), 2. |

| ↑13 | Rochonne Abrams, “The Colonial Childhood of Meriwether Lewis,” The Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, Vol. 34, No. 4, Part 1 (July 1978), 218-19. |

| ↑14 | William E. Foley, Wilderness Journey: The Life of William Clark (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2004), 4. |

| ↑15 | Daniel Justin Herman, Hunting and the American Imagination (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001), 68-74. |

| ↑16 | Desiderius Erasmus (d. 1536) In Praise of Folly (1511; London, 1887), 87. |

| ↑17 | Peter S. Onuf, “Liberty, Development, and Union: Visions of the West in the 1780s.” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 43, no. 2 (April 1986): 188, 189, 195. |

| ↑18 | Herman, Hunting, 41-45. |

| ↑19 | Notes on the State of Virginia (1787), Query XIX. |

| ↑20 | Hector St. John de Crèvecœur (1735-1813) Letters from an American Farmer (London, 1782; Philadelphia, 1793; New editiion with introduction and notes by Warren Barton Blake; New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1912), 70-72. After the American Revolution Crèvecœur became the French Consul at New York. He returned to France in 1813. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.