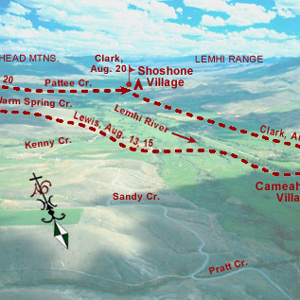

Having reached the end of the navigable Missouri, the captains—aided by Lemhi Shoshone Chief Cameahwait, Sacagawea‘s brother—begin acquiring horses, making pack saddles, and caching supplies they can no longer take with them.

With the help of the Lemhi Shoshones, everything is carried across the Continental Divide at Lemhi Pass. Clark and their new guide they call Toby, scout the Salmon River and find it is not navigable.

After nearly three weeks with the Shoshones, the expedition moves down the Lemhi River valley and heads up the North Fork Salmon River. The captains ignore Toby’s advice to follow the Indian Road, and they are forced to spend a snowy night near the summit of Lost Trail Pass.

Dropping down from Lost Trail Pass, the Flathead Salish give them a warm welcome and sell them some horses. The expedition then proceeds down the Bitterroot River Valley to Travelers’ Rest where they have yet to cross the Bitterroot Mountains.

Aided by the Lemhi Shoshone Chief Cameahwait, Sacagawea‘s brother, they begin a slow process to acquire horses and to move necessary equipment and supplies across Lemhi Pass. A Lemhi Shoshone guide named Toby joins them. Between the Lemhi and Bitterroot valleys they stumble across the Lost Trail divide. They buy more horses from the Salish and proceed down the Bitterroot River to Travelers’ Rest.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Flathead Salish

The first whites to encounter the Salish in person were the Lewis and Clark Expedition at Ross’ Hole. Although the journalists had much to say about the encounter, the Salish have said far more.

The Lemhi Shoshones

by Stephen E. Ambrose

The Lemhi Shoshones were the first Indians they had seen since leaving the Hidatsas and Mandans. In describing them, Lewis was breaking entirely new scientific ground. His account is therefore invaluable as the first description ever of a Rocky Mountain tribe, in an almost pre-contact stage.

Across the Great Divide

Over Lemhi Pass

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Below the summit of today’s Lemhi Pass, Lewis said that he had reached “the most distant fountain of the waters of the mighty Missouri in surch of which we have spent so many toilsome days and wristless nights.”

Synopsis Part 4

Lemhi Valley to Fort Clatsop

by Harry W. Fritz

After trading for horses with Sacagawea’s people, the expedition turned north and then west, on what would indisputably be the most exhausting and debilitating segment of the entire journey, the passage across the Bitterroot Mountains.

Cameahwait’s Pipe

Ceremony of the pipe

by Joseph A. Mussulman

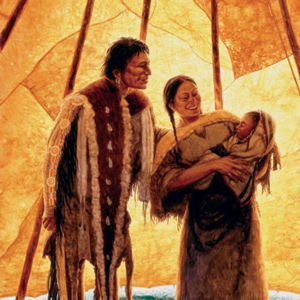

When Cameahwait took Lewis into the shelter of the only leather lodge his people had been able to save from the Hidatsas’ depredations of the previous spring, Lewis knew for sure he was among good friends.

Meeting the Shoshones

by Joseph A. Mussulman

A few more Shoshones came in sight. Making all the benevolent signs and sounds he could think of, pondering ways to bring the wary Indians within talking distance, Lewis finally touched the hand of an elderly woman, and the spark of international friendship was struck.

The Lemhi Valley

Hospitable people

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and his four companions crossed over the dividing ridge on the west side of the upper Missouri River basin and the Columbia drainage, then descended a dusty, well-traveled Indian road for some miles down into a “handsome little valley” among the sources of the Columbia River basin.

Cameahwait’s Geography Lesson

by J. I. Merritt

When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark encountered the Shoshone Indians in August 1805, one or the other—or more likely both, sat down with Cameahwait, the chief of the tribe’s Lemhi band, to learn as much as possible about the region’s geography.

Promises to Keep

Lewis's threats and promises

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Pretending to have been insulted by their accusation, Lewis pompously declared that “if they continued to think thus meanly of us…they might rely on it that no whitmen would ever come to trade with them or bring them arms and amunition.”

Lewis’s Shoshone Tippet

Cameahwait's gift

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Cameahwait and some of his people agreed to help the Corps of Discovery carry its baggage over the divide. In the early afternoon. “We now dismounted,” wrote Lewis, “and the Chief with much cerimony put tippets about our necks such as they temselves woar.”

Lewis’s Birthday Meditation

A "sadly interesting passage"

by Joseph A. Mussulman

It has been remembered as “the most gloomy self-examination of the entire journal,” and “a passage of unreasonable melancholy,” of poignant sadness and self-doubt.

Shoshone Travel Advice

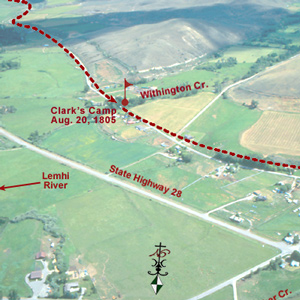

Leaving Withington Creek Village

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis was still at Camp Fortunate directing the digging of a cache and the making of packs and pack-saddles for the portage across the divide. Meanwhile, Clark and his contingent left to see whether the Salmon River was as bad as Cameahwait had said.

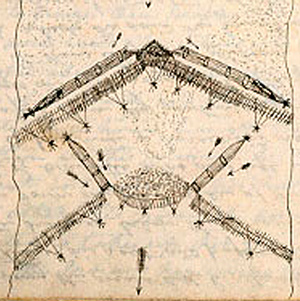

The Shoshone Fish Weirs

by Joseph A. Mussulman, Steve F. Russell

Clark visits a Shoshone camp on the west bank of the Lemhi River near today’s Salmon City, where he and his men are fed on “Sammon boiled, and dried Choke Cher[rie]s,” and taken on a sight-seeing trip to the nearby permanent fishing weirs.

The Shoshones’ Three Roots

Examining Shoshone foods

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis learned about three unfamiliar species of edible roots–a bushel of them altogether. The Shoshones who were encamped nearby helped him sort them out, and told him how they were customarily prepared.

The Salmon River

A river of no return

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On the 23 August 1805, the centuries-old fantasy of a “water route across the continent for the purposes of commerce” dissolved in the roar of an unimaginable torrent–one of the most dangerous, unforgiving rivers in North America, that would later be called “The River of No Return.”

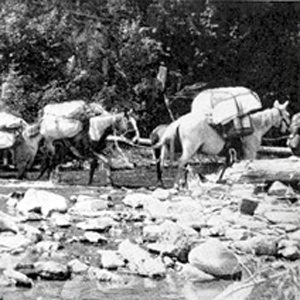

Horse Packing

Traveling with horse and mule

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Loading and handling a packhorse is hard work. It demands not only a great deal of physical strength and endurance, but also an eye for balancing a load on the first try, a head full of horse sense, the patience of a saint, and lots of experience.

Leaving the Lemhi Valley

Detour at Tower Creek

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Salmon winds tortuously through a seven-mile-long canyon where the vertical walls at that time crowded the riverbanks so tightly in several places that Clark and his party were compelled to clamber over “four mountains verry Steap high & rockey.”

The Lost Trail Divide

Leaving the Indian road

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Continuing north up the North Fork Salmon River, they leave a good Indian road and must cut their own trail. Were they lost? Sergeant Gass’s laconic remark gives us a hint: “This was not the creek our guide wished to have come upon.”

Lost Trail Pass

Uncertainty

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Where did they camp? This was not the only time Toby was unsure of himself, nor that the captains were temporarily baffled, but it is perhaps the one that most readily invites study and discussion.

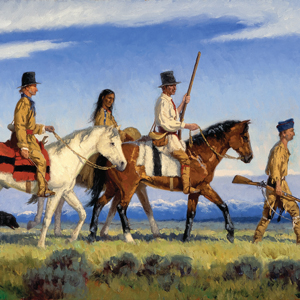

Ross’ Hole

The story behind Russell's painting

by Patricia M. Burnham

The story behind Charles M. Russell’s 1912 painting of the expedition meeting the Bitterroot Salish at Ross’ Hole, one of the great works of Western American art.

Meeting the Salish

Multiple perspectives

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The story of Lewis and Clark meeting the Flathead Salish on 4 September 1805 at Ross Hole is told by one expedition member, four Salish Indians, and one western artist.

The Trapper Peaks

Bitterroot Mountain sentinels

by Joseph A. Mussulman

On 7 September 1805, the day after they left the Salish people at Ross’s Hole, the Corps proceeded north down the Bitterroot River valley. “The foot of the Snow toped mountains approach near the river on the left,” wrote Clark.

The Bitterroot River

Tum-sum-lech, no salmon!

by Joseph A. Mussulman

“The stream appears navigable,” he had earlier confided to his journal in reference to the Bitterroot River, “but from the circumstance of their being no sammon in it I believe that there must be a considerable fall in it below”

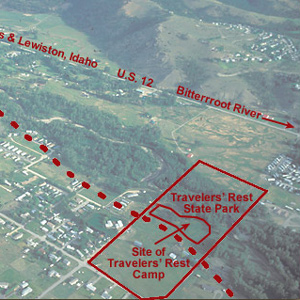

Travelers’ Rest

Hub of the west

by Joseph A. Mussulman

In the afternoon of 9 September 1805 they turned westward at a creek they dubbed Travelers’ Rest, today known as Lolo Creek. They stopped at a gathering place that Indians had been using for that same purpose for thousands of years.

Naming Travelers’ Rest

Thinking of South Carolina?

by Joseph A. Mussulman

Lewis and Clark and their men camped on 9–10 September 1805 and again on 30 June though 2 July 1806 beside a stream they called “Travelers Rest Creek.” Meriwether Lewis may have seen or sensed a comparison between it and the Travelers Rest in South Carolina.

Paxson’s Travelers’ Rest

The artist's interpretation

by Joseph A. Mussulman

At Lewis’s right is Clark’s servant, York, dressed in blue as befitted a personal slave at that time. The Indian squatting at Lewis’s left hand is Toby, the Shoshone guide the captains had hired to lead them across the Bitterroot Mountains toward the Columbia River.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.