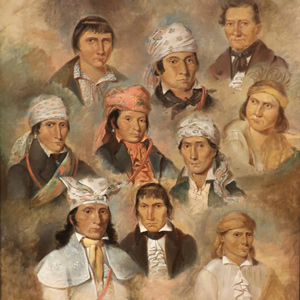

After European contact, Algonquian-speaking people dispersed variously to areas in today’s southeast United States, Ohio River states, Mississippi River states, Nebraska and Texas, and even Mexico. The Lewis and Clark Expedition encountered speakers on the Ohio, the Mississippi River, throughout the plains, and as far as the Two Medicine River in Northwestern Montana.

Algonquian-speaking Nations Encountered

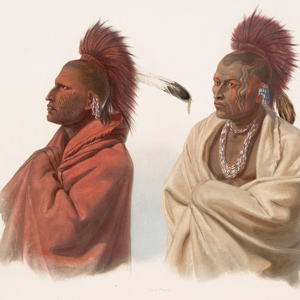

The Sauks and Foxes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

To outsiders in 1803, the Sauk and Fox people living on the Mississippi River in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin were seen as one people. Both peoples spoke the Sauk-Fox-Kickapoo dialect of Algonquian and had similar cultures and economies.

The Cheyennes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Many, including the expedition members, misheard the people’s name as ‘chien’—French for ‘dog’. Their name actually comes from the Sioux exonym shahíyena, perhaps meaning ‘people of alien speech’. The captains thought that they might make good trading partners.

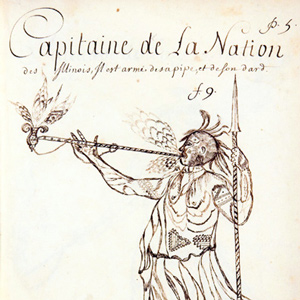

The Illinois Tribes

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The expedition set up camp near a town named after the Cahokia, one the Illinois tribes. The captains reported that Missourias, the Illinois, Cahokias, Kaskaskias, and Piorias were nearly destroyed by the Sauks and Foxes.

The Lenape Delawares

by Kristopher K. Townsend

About 1784, a small group of Shawnee and Delaware migrated from Illinois to southeastern Missouri. Ten years later, the Spanish encouraged members in Illinois to migrate the Cape Girardeau area as a way to protect their own settlements from the Osage.

Perhaps more than any North American people, the Kickapoo exemplify the transitory nature of the native nations encountered during the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In 1803, there was at least one village near Ste. Genevieve on the Mississippi River.

The Atsinas

by Kristopher K. Townsend

Today, they are called the Atsina or Gros Ventre, but their names in the historical literature—Big Bellies, Gros Ventre and Minnetares—cause confusion even to this day. The expedition never met them, but their presence affected the expedition in several ways.

The Shawnees

by Kristopher K. Townsend

As soon as the expedition boats arrived at the Mississippi River, the captains began counting Shawnee people. The Estimate of the Eastern Indians reports that 600 “Shawonies” were living on the “apple River near Cape Gerardeau.”

The Potawatomis

by Kristopher K. Townsend

By 1800, the Potawatomi had successful traded with the French to the north and the Spanish in St. Louis. They resided in a large region surrounding the southern half of Lake Michigan between the Mississippi River and Lake Erie and extending south to the mouth of the Illinois River.

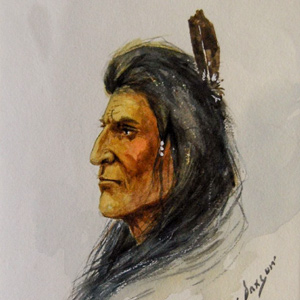

The Blackfeet

by Kristopher K. Townsend

They commonly called themselves saokí•tap•ksi meaning ‘prairie people.’ The meaning ‘people with black feet’ comes from exonymns—the names given by other, external tribes. Historically, several related groups comprise the Blackfoot or Blackfeet people.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.