The following are extracts from an article reprinted with permission from Western Pennsylvania History, Winter 2009-2010. The original reprint is from We Proceeded On, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation.[1]William K. Brunot, “The Building of the Barge: The Creation of the Lewis and Clark Flagship,” We Proceeded On, February 2022, Volume 48, No. 1. The full re=print is provided at … Continue reading

The circumstances surrounding the building of the vessel that was used by Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their exploring expedition in 1803 have been uncertain for years. This boat, generally called a “keelboat,” should more accurately be called a barge, or military galley, after a careful look at its design.[2]Patricia Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” Pittsburgh Post Gazette Sunday Magazine, 3 August 2003; Leland D. Baldwin, The Keelboat Age on Western Waters (Pittsburgh: University of … Continue reading The differences between the two types of boats are significant. In his journal during the voyage, Lewis himself, and others who saw it, called his big boat a “barge.”[3]Pierre Choteau in letter to William Henry Harrison, 22 May 1805, calls the Lewis boat “the barge of Capn. Lewis,” Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with … Continue reading The drawings of this boat made by Captain William Clark and other references in the journals also establish its type clearly.[4]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Definitive Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:161-164.4. See also Lowry, “Who Built the Big … Continue reading For many years, the fact that Lewis went down the Ohio River with his barge and other smaller boats was not widely known. There is a well-documented tradition that one or more of the Lewis boats was built in Elizabeth, Pennsylvania, but most historians today conclude that his barge was built in Pittsburgh. Until 2003, the belief was that it had been built at one of the boatyards along the banks of the Monongahela River (i.e., near Pittsburgh). The research outlined in Patricia Lowry’s 3 August 2003, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article, “Who Built the Big Boat?” pointed to a new possibility—that the Lewis boat was built at Fort Fayette (i.e., in Pittsburgh). This stockade, erected in 1791 on the banks of the Allegheny River, protected settlers from Indian raids after Fort Pitt had fallen into ruin. It is known that Captain Lewis had his supplies stored at Fort Fayette in preparation for his departure down the Ohio River.[5]Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” A painting of the city of Pittsburgh believed to have been executed in 1804, when studied in detail recently, revealed not only an image of Fort Fayette, but a building on the shoreline that has the features of a boatbuilding structure.

Western Military Boats

The famous Revolutionary War soldier General George Rogers Clark, William Clark’s older brother, used armed galleys in his campaigns against the British and their Indian allies on the western frontier. Before the summer of 1780, with his usual promises to pay the boatbuilders, Clark engaged workmen to construct 100 boats, mostly cheap flatboats, which were to be completed within two months and used to transport provisions on his planned 1780 expedition.[6]James Alton James, The Life of George Rogers Clark (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1928; reprinted St. Clair Shores, MI: Scholarly Press, 1970), 193. At that time, Jacob Myers was with Clark in Illinois. On 21 July 1780, Myers sent a bill to the governor of Virginia listing “cost and items used … to make 7 boats for the state of Virginia, cost of 1,765 pounds currency for calking, nails, boxes for artillery and horses.”[7]Index, George Rogers Clark Illinois Regiment, Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Illinois, Sons of the Revolution in the State of Illinois, Record Number 6288-4-450-452, 21 July 1780. See also … Continue reading Jacob Myers is mentioned again in records of 20 September 1780, and 20 February 1781.[8]Ibid. Record Numbers 8363-5-354 and 8358-5-349. During the spring and summer of 1781, General Clark was back in Pennsylvania attempting to raise troops for another expedition.[9]Edgar Wakefield Hassler, Old Westmoreland: A History of Western Pennsylvania During the Revolution (Pittsburgh: J.R. Weldin & Company, 1900; reprinted Westminster, MD: Heritage Press, 1970), 131. He embarked from Pittsburgh on August 8 with three field pieces and only 400 men.[10]James, The Life of George Rogers Clark, 242. Jacob Myers was still attached to Clark’s army on 22 March 1782, when a bill was sent from Louisville for “entries for items and cash distributed to various officers and persons—references to corn, meat, and other items.” Persons owed included Jacob Myers. Many letters and bills were sent to Virginia governor Benjamin Harrison at that time for canoes, boats, barges, paddles, oars, anchors, nails, calking, calking irons, mallets, augers, hemp, cordage, and other boat-building supplies.[11]George Rogers Clark Papers, Virginia State Library and Archives, The Illinois Regiment, Microfilm Reel #10, Record Number 14683-9-102-105. Major Isaac Craig had been ordered to Fort Pitt with artillery and military supplies. He reached his station in Pittsburgh on 25 June 1780,[12]Free & Accepted Masons, History of Lodge No. 45 F. & A.M. 1785-1910 (Pittsburgh: Press of Republic Bank Note Company, 1912), 93. and was still directing boatbuilding operations in 1790 when he paid $2.66 and 2/3 cents a foot for most of the keelboats and barges he bought.[13]Baldwin, Keelboat Age.

Of course, there were other armed barges traveling the Ohio whose designs were nearly identical to the vessel that Lewis and Clark used in 1803. On 21 March 1791, John Pope, traveling from Pittsburgh to New Orleans, encountered a “Keel-bottomed boat with a square sail” bound upriver from New Madrid, making two-and-a-half miles an hour without the aid of oars. When he neared Natchez, Pope found a Spanish fleet consisting of a governor’s barge occupied by Governor of Spanish Louisiana Don Manuel Luis Gayoso de Lemos y Amorin (1747-1799) accompanied by other vessels. This “galley” had twenty-eight men, twenty-four oars, one six-pounder, and eight swivel guns. A drawing of this galley shows a remarkable similarity to the Lewis and Clark big boat, which was built twelve years later.[14]Baldwin, Keelboat Age.

General Wayne’s Boats

Pittsburgh 1795

From Palmers Pictorial Pittsburgh and Prominent Pittsburghers Past and Present, 1758–1905, R. M. Palmer, ed. (Pittsburgh: 1905).

Above: Fort Fayette and “U.S. Wharf” are outlined in red. At the point of land, is Fort Pitt. For Palmer’s 1905 Pictorial, this map was accurately re-drawn from an earlier map. For A. G. Haumann’s version of this map, see the original article at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol48no1.pdf#page=10.

By fall 1791, much of Fort Pitt had been torn down. Major Isaac Craig, quartermaster general at Fort Pitt and then Fort Fayette, wrote to Secretary of War Henry Knox on October 6 that William Turnbull and Peter Marmie were continuing to pull down and sell the materials from the fort. Knox responded on December 16, directing Craig to build a new fort for the protection of Pittsburgh. Craig decided upon the name of Fort Lafayette. Knox approved, but the name “Fayette” was used thereafter.[15]C. Hale Sipe, Fort Ligonier and Its Times (Harrisburg: The Telegraph Press, 1932), 627-29. Fort Fayette was on the south side of the Allegheny River about a quarter of a mile east of Fort Pitt. It sat within about a hundred yards of the bank on beautiful rising ground,[16]George Dallas Albert, Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania: Volume 2, The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania (Harrisburg: Clarence M. Busch, State … Continue reading straddling present-day Penn Avenue between Ninth and Tenth streets. The structures were enclosed in a square stockade surrounding about an acre. Four bastions contained blockhouses, a brick arsenal, and a barracks with thirty rooms. On 5 May 1792, Captain Thomas Hughes moved his men to the fort. General Anthony Wayne commanded the third army sent against the Indians north of the Ohio, arriving at Pittsburgh on 14 June 1792.[17]Sarepta C. Kussart, The Allegheny River (Pittsburgh: Burgum Printing Company, 1938), 32-37. Wayne immediately plunged into the business of organizing and training his “army”—just forty recruits, plus the corporal’s command of dragoons that had accompanied Wayne across the state.[18]Paul David Nelson, Anthony Wayne: Soldier of the Early Republic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 228. The number in his force grew rapidly and the “army” was renamed the “Legion of the United States.” General Wayne himself headquartered at the southeast corner of Liberty and West streets, while his troops encamped on Suke’s Run across the Allegheny River.

The quartermaster and his supplies were kept at Fort Fayette. James O’Hara and Major Craig bought flour, meat, forage, and other supplies, and contracted boats for the army’s use.[19]Leland D. Baldwin, Pittsburgh: The Story of a City 1750-1865 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1938), 108. By the time of Wayne’s departure, Major Craig had built forty-two boats, mostly flatboats, for his troops at Pittsburgh. They were larger than those he had purchased for army use the year before.[20]Letter from Major Isaac Craig to Secretary of War Henry Knox, 11 March 1792. Isaac Craig Papers 1768-1868, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh General Archival Collection, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In a letter to General Knox dated 30 November 1792, Craig reported that at an early hour, the artillery, infantry, and rifle corps (except for a small garrison) left Fort Fayette, embarked, and descended the Ohio to “Legionville.” As soon as the troops had embarked, the general went on board his barge under a fifteen-gun salute from a militia artillery corps at Fort Fayette.[21]Letter from Major Isaac Craig to Secretary of War Henry Knox, 30 November 1792, in Busch, Frontier Forts, 131. The salute commemorated the fifteen states in the union and voiced the army’s gratitude for the “politeness and hospitality” that the officers of the Legion had experienced from Pittsburgh’s citizens. Among Wayne’s troops was William Clark, commissioned as a first lieutenant in the fourth sub-legion in Wayne’s western army.[22]Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905), 1:xxvii. Thus Lieutenant Clark would have known well the builders and characteristics of the vessels carrying these troops. By June 1793, Major Craig, the deputy quartermaster general, forwarded 104 flatboats to Wayne’s expedition laden with provisions, horses, and equipment in addition to goods sent by other craft.[23]Baldwin, Keelboat Age.

The Myers Packet-Boat Service

It seems likely that Jacob Myers participated in building some of General Wayne’s barges because Craig contracted out work and because, immediately after Wayne’s departure, Myers built the barges used in his own “Packet Service,” the first boat of which was ready to leave Pittsburgh in October 1793. Because the fortunes of boatbuilders undoubtedly waxed and waned as the demand from the military swelled and stopped, Myers might have been in need of a new market. Boat carpentry is a highly skilled occupation, far more complicated than homebuilding. Every frame, plank, and rail is curved, twisted, or sawn at angles, and most have to take on a three-dimensional shape. Fittings are curved, cast, or carved, and even sails are not flat. The boatbuilder serves a long apprenticeship and can be in great demand for intermittent periods. In 1793 Jacob Myers offered his fortnightly service between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati on boats propelled by oars and sails. These were no flatboats; they were intended for continuous service up and down the river. The advertisements, which first appeared in The Pittsburgh Gazette on 19 October 1793, and in Cincinnati’s Sentinel of the Northwest Territory on 11 January 1794, described the first regularly scheduled boat service on the Ohio River between the two cities.[24]Mark Welchley, “Ohio Packet Boats,” Milestones, 7:2 (Spring 1982) accessed at www.bcpahistory.org. One reference mentioned that there were to be four boats of twenty tons each, a size within the range Meriwether Lewis specified in his initial list for the expedition in 1803.[25]Baldwin, Keelboat Age. The enterprise, however, appears to have been short-lived. Isaac Craig clearly knew of the Myers boat service, and in May 1794 wrote that the idea of passenger packet boats ought to be abandoned.[26]Baldwin, Pittsburgh, 140,141. The government mail boats that operated from 1794 to 1798 carried a few passengers, but thereafter no regular service appears to have been available on the upper Ohio until the advent of the steamboat. Presumably the ease and cheapness with which boats could be purchased or passage obtained on the boats of others made packet service unprofitable.[27]Baldwin, Keelboat Age.

The Whiskey Rebellion Era

Washington Reviewing the Western Army at Fort Cumberland, Maryland

Frederick Kemmelmeyer (1760–1821)

Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1963, Metropolitan Museum of Art, www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/11302. (cropped)

During the Whiskey Rebellion, what became known as “Braddock’s Defeat” was the beginning of George Washington’s reputation as great military leader. He had no command in Braddock’s Expedition, but during the unauthorized retreat following Braddock’s fatal wounding, Washington organized a rear guard that helped the forces disengage.[28]Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York: Alfred E Knopf, 2000), 103–4. Lewis likely participated in the ceremonies surrounding President George Washington at Fort Cumberland in October 1794. According to the journal of Robert Wellford, “every regiment was drawn up in excellent order to receive him, & as he passed the line of Infantry he deliberately bowed to every officer individually. The Artillery at the same time announced his arrival.”[29]Robert Wellford, “A Diary Kept by Dr. Robert Wellford, of Fredericksburg, Virginia, during the March of the Virginia Troops to Fort Pitt (Pittsburg) to Suppress the Whiskey Insurrection in … Continue reading—KKT, Ed.

In 1794, a federal army unit was sent to western Pennsylvania to help put down the Whiskey Rebellion. Meriwether Lewis, who was then twenty years of age, had enlisted in the army as a private and was part of this unit.[30]Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:xxv. They camped on the Monongahela River about fifteen miles above (i.e., south of) Pittsburgh on Andrew McFarlane’s farm at what is now the riverfront town of Elrama, two miles upriver from Elizabeth. McFarlane’s ferry landing was on the west side of the Monongahela River. Lewis may have become familiar with the Elizabeth town boatyards and boatbuilders at that time. At the same time, Fort Fayette was the center of the rapidly changing forces involved in the rebellion and was used for incarcerating some of the prisoners.[31]Baldwin, Pittsburgh, 124-28. Lewis could have seen Jacob Myers’ advertisements for his packet-boat service in The Pittsburgh Gazette, and may have seen his boats firsthand in Pittsburgh. The 1795 Pittsburgh map on which the Fort Fayette plan is shown most clearly also shows a “U.S. Wharf” on the shore adjoining the fort. The modern definition of the word “wharf” differs somewhat from the definition at this time, which could simply mean a shore or landing place. For example, the area known as the “Monongahela Wharf” was a riverbank until well after 1850.

Early in 1796, the same year Clark retired from the army, Georges Henri Victor Collot, a French military officer who had fought on the American side during the Revolution, passed through Pittsburgh, giving us some insight into Fort Fayette and boatbuilding in the city. His mission was secret: he was to assess, for the information of the French government, the strength of the fortifications along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. He visited Fort Fayette and had a low opinion of it, stating, “On a dark night, four grenadiers, with a dozen faggots of dry wood, might burn the fort and all the garrison, and not let a single individual escape.” He also remarked about the cost of boats at that time, saying that keelboats and barges were selling further up the Monongahela at $1.50 a foot. He stated that Pittsburgh prices were exorbitant.[32]Baldwin, Keelboat Age.

Pittsburgh Galleys

Two years later, during a period of trouble with France, two row galleys were built at Pittsburgh under the supervision of Major Craig who was in charge of operations at Fort Fayette. These galleys were forty-five feet in length and thirteen in beam. They had two masts and were equipped with sails and rigging. There were thirty oars of differing lengths, and the row benches were constructed so that they could be folded away. The first galley, the President Adams, was launched on 19 May 1798, with General James Wilkinson presiding.[33]Baldwin, Keelboat Age. Tarleton Bates, Virginian and friend of Meriwether Lewis, wrote to his brother Frederick Bates six days later, “On Saturday the nineteenth, precisely at 2 PM, the first galley was launched at this place. It was said to be a very beautiful launch, she slid a most unusual distance, I believe 126 feet.”[34]Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” The galley departed down the Ohio on 8 June 1798, with General Wilkinson and his suite on board, followed by six large flat-bottomed boats and several smaller craft. Because of low water in the Ohio River, the second galley, the Senator Ross, was not launched until nearly a year later, on 26 March 1799. She carried a twenty-four-pound gun in her bow and some swivel guns on deck. The launching was heralded by a salute fired on board and returned by the guns of Fort Fayette. By April, she had departed for the Mississippi. By then, the anticipated war with France had been averted.[35]Kussart, The Allegheny River, 33. As Major Craig had overseen the construction of the President Adams and the Senator Ross, it is plausible that both vessels were built at the Fort Fayette yards. The firing of a salute from the fort would make sense only if the boats had been launched there. The artillery had a limited effective noise range and there were no means of communication to coordinate such a firing had the galleys been launched further away.

Lewis’s Requirements

In September 1800, Meriwether Lewis returned to the Indian frontier. While in Pittsburgh, he had direct dealings with Major Craig.[36]See Craig’s note of Sept. 15, 1800, Craig Papers, AA/Craig/VII; Abstract of Forage, Sept. 9, 1800, AA/Craig/V.c; also VII.e, Sept 15, 1800. See John Bakeless, Lewis & Clark, Partners in … Continue reading On December 5, Lewis was promoted to captain and on one of his trips traveled down the Ohio with a twenty-one-foot bateau and a pirogue, thus gaining real experience on the western rivers.[37]Richard Dillon, Meriwether Lewis: A Biography (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1965; reprinted Lafayette, CA: Great West Books, 2003), 25.

In 1801, Lewis was in Pittsburgh off and on during his military trips where he likely had contact with Major Craig again.[38]Lewis’ receipt to Isaac Craig, 22 March 1801. Receipt Book, Craig Papers; Account Book, Craig Papers, AA/Craig/IIIc. There are various references to Lewis in these papers. See Bakeless, Lewis … Continue reading Lewis could probably not have avoided seeing Myers and his boats during this period if Myers were still living in or near Pittsburgh. Late in 1801, Lewis received the invitation to become secretary to President Thomas Jefferson. In 1802, Jefferson and Lewis started planning the great western expedition, and by spring 1803, President Jefferson and Lewis had completed their planning. On Jefferson’s orders, Lewis traveled to Philadelphia to study navigation, surveying, medicine, and biology with top experts. He also purchased large quantities of military and civilian supplies and trade goods.

In a letter to Jefferson in January 1803, Lewis offered an estimate of the cost of his “means of transportation:” $430.[39]Thwaites, Original Journals, Appendix, 210. Also see “Articles Purchased for the Expedition,” in Frank Bergon, ed., Journals of Lewis and Clark (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), xxxvi. … Continue reading He listed his “Articles Wanted” in detail in his May-June summary. Among those items were his “means of transportation:”

- 1 Keeled Boat light strong at least 60 feet in length her burthen equal to 8 Tons.

- 1 Iron Frame of Canoe 40 feet long

- 1 Large Wooden Canoe

- 12 Spikes for setting-poles

- 4 Boat Hooks & Points Complete

- 2 Chains & Pad-locks for confining the Boat & Canoes &c

No record of the order or contract for the big boat’s construction has been found, and so it is not known who was selected as contractor. What does exist, however, is an example of how Lewis would have implemented such an order. In a lengthy letter to Jefferson on 20 April 1803, concerning his boat and other transactions, he stated:

I have also written to Dr. Dickson, at Nashville, and requested him to contract in my behalf with some confidential boat-builder at that place, to prepare a boat for me as soon as possible, and to purchase a large light wooden canoe: for this purpose I enclosed the Dr. 50. dollars, which sum I did not concieve equal by any means to the purchase of the two vessels, but supposed it sufficient for the purchase of the canoe, and to answer also as a small advance to the boat-builder: a description of these vessels was given. The objects of my mission are stated to him as before mentioned to the several officers.[40]Lewis to Jefferson, from Philadelphia, 20 April 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 214; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:38.

Lewis wrote again to Jefferson on 29 May 1803, from Philadelphia: “I have written again to Dr. Dickson at Nashville, (from whom I have not yet heard) on the subject of my boat and canoe.”[41]Lewis to Jefferson, from Philadelphia, 29 May 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 214; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:53. These two letters are revealing. First, they illustrate how Lewis might have ordered the big boat in Pittsburgh. Further, they show that as late as 29 May 1803, a day or so before he left Philadelphia, he was still trying unsuccessfully to get his big boat built in Nashville, Tennessee! He then was intending to travel downriver from Pittsburgh with all his goods in smaller boats and by overland transport.

The Pittsburgh Shipments

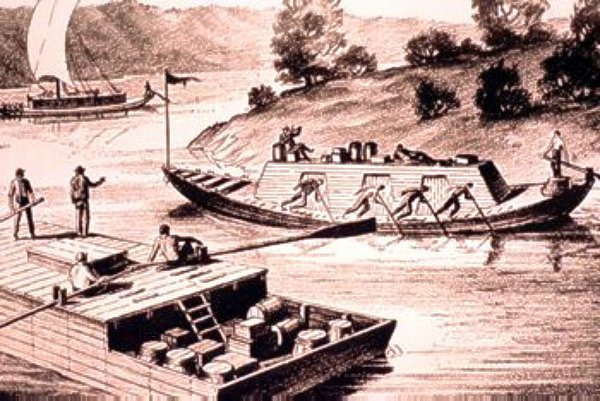

Above: A flatboat floats down the river while a keelboat is poled against the current. The Expedition’s military barge was neither of these.—KKT, ed.

At this time, Lieutenant Moses Hooke was in command at Fort Fayette; Lewis had a high regard for his character and competence.[42]Lewis to Jefferson, 26 July 1803. Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 264-65; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:113-14. Lewis also noted that Major Craig, who had always been associated with Fort Fayette, was also present in Pittsburgh at that time and could take care of his stores if necessary.[43]Lewis to Jefferson, 26 July 1803. Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix 264-65; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:113-14. While still in Philadelphia, Lewis shipped his goods from there to the Indian Department, Pittsburgh, which was located at Fort Fayette.[44]Bergon, Journals of Lewis and Clark, xliv. The list of charges taken out on Lewis’ account in Philadelphia included:

- Transportation of public stores from Philadelphia to Indian D. Pittsburgh

- 18 small falling axes to be furnished at (ditto) Indian D.

- 1 Boat and her caparison, including spiked poles, boat hooks & toe line to be furnished at Pittsburg

Lewis also ordered “A strong waggon—wt. From here (Philadelphia) 2700—to be increased to 3500 or more” and instructed that “the box of mathematical instruments to be sent for Mr. Patterson & well secured with canvas—mark’d ‘This side up’ on the top—& and particular charge given the waggoner respecting it.”[45]Bergon, Journals of Lewis and Clark, xliv. These instructions indicate that the equipment purchased in Philadelphia was to go to Pittsburgh by wagon—not to some intermediate location on the Monongahela River such as Elizabeth. Fort Fayette, moreover, would have made more sense as a destination for the items, considering the quantity, value, purpose, and ownership of this shipment of military equipment and trade goods. Lewis would hardly have shipped them to an inn, to the post office, to a boatyard on the Monongahela, or to the dilapidated Fort Pitt. By this time, both Lewis and Clark knew every aspect of the military boats used on previous river campaigns, and would have most likely desired an armed galley—a craft that could mount and fire cannons and go upstream. Although Lewis wrote that he wanted a “keeled boat,” an actual keelboat with full-length cabins would have been the wrong design for a big expedition up the Missouri. Lewis and Clark had to carry a huge load of supplies and trade goods as well as a large crew. Keelboats cannot mount a large sail and they have only a single oar for steering, which would have been too weak for a boat as large as the one Lewis and Clark needed. Barges or galleys have mounted rudders. A keelboat’s roof oars would have been too inefficient and too few for their big crew. Oars would have to be mounted lower down to be functional. The main power for the boat, rowing, would have dominated the whole design of Lewis and Clark’s boat selection, and thus led them to select the very type of boat that they did, which was a barge.

Lewis’s Pittsburgh Arrival

It is now clear, though, that the order for the big boat could not have reached Hooke and the Pittsburgh boatbuilder before the first week of June 1803! Having finished his business in Philadelphia, Lewis returned to Washington on the first of June. He left for Harpers Ferry on July 5, where he purchased 3,500 pounds of guns and other supplies. These goods were shipped by wagon to Pittsburgh. Lewis, on the move again by July 8, headed north. When he arrived in Pittsburgh on July 15, Lewis wrote to Jefferson at 3 P.M.:

I arrived here at 2 O’clock, and learning that the mail closed at 5 this evening hasten to make this communication, tho’ it can only contain the mere information of my arrival. I have not yet seen Lieut. Hook nor made the enquiry relative to my boat, on the state of which, the time of my departu[r]e from hence must materially depend: the Ohio is quite low, but not so much so as to obstruct my passage altogether.[46]Lewis to Jefferson, 15 July 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:110.

Lewis had ridden in from the south. If his boat were being built anywhere along the Monongahela River—at any place between Elizabeth and the boatyards at Pittsburgh—Lewis might have ridden near the boatbuilding site upon entering the city. In fact, the post office was located in the southern section of the city throughout those years, near the boatyards on the Monongahela shore.[47]The post office was at Front and Ferry streets. See item 37 in Lois Mulkern, “Pittsburgh in 1806,” Pitt: A Quarterly of Fact and Thought at the University of Pittsburgh, Spring 1948; also … Continue reading Lewis did not know yet where his boat was being built, nor did he know the identity of the builder. He had to learn both from Lieutenant Hooke, commandant at Fort Fayette and in charge of Lewis’ supplies there. In Lewis’ letter to Jefferson on July 22, he referred to “The person who contracted to build my boat. ” Lewis never indicated that he himself had selected or contracted with a particular builder. He did not know which yard to visit, and it would have been quite pointless for him to ride around the city looking for Lieutenant Hooke, Major Craig, or the boat that late in the afternoon. Captain Lewis settled somewhere upon his Pittsburgh arrival at 2 p.m. and was writing to Jefferson shortly thereafter. Perhaps he stopped at Jean Marie’s Inn on the southeast edge of town or at William Morrow’s Sign of the Green Tree tavern, where he had stayed previously. Perhaps he stayed with Major Craig at his house at Fort Pitt or with his close friend from Virginia, Tarleton Bates.

Pittsburgh Frustrations

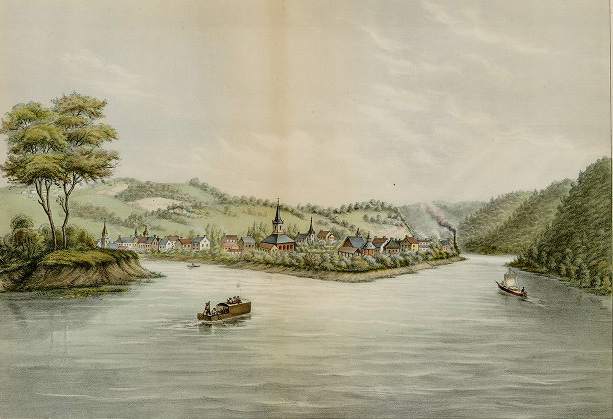

“View of the City of Pittsburgh in 1817”

by Charles O. Lappe

Chromolithograph, 12.5 x 18.25 inches. Historic Pittsburgh collection hosted by the University of Pittsburgh.

Two early boats ply the river and a steam locomotive can be seen coming down the Monongahela River. The lithograph is inscribed:

Taken from a sketch drawn by Mrs. E. C. Gibson, Wife of Jas. Gibson, Esg. of the Philada. Bar, while on her Wedding Tour in 1817.

In his letter of July 22, Lewis wrote that he had expected his boat to be nearly finished when he reached Pittsburgh but was dismayed to find it in an early state of construction:

Yours of the 11th & 15th Inst. were duly received….

The person who contracted to build my boat engaged to have it in readiness by the 20th inst.; in this however he has failed; he pleads his having been disappointed in procuring timber, but says he has now supplyed himself with the necessary materials, and that she shall be completed by the last of this month; however in this I am by no means sanguine, nor do I believe from the progress he makes that she will be ready before the 5th of August; I visit him every day, and endeavour by every means in my power to hasten the completion of the work….

The Waggon from Harper’s ferry arrived today, bringing everything with which she was charged in good order.

The party of recruits that were ordered from Carlisle to this place with a view to descend the river with me, have arrived with the exception of one, who deserted on the march, his place however can be readily supplyed from the recruits at this place enlisted by Lieut. Hook.[48]Lewis to Jefferson, Pittsburgh, 22 July 1803. Original ms in the Bureau of Rolls: Jefferson Papers, series 2, vol. 51, doc. 100. Reproduced in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 260; … Continue reading

Though Lewis never mentions the builder of the expedition vessel by name, Jacob Myers was in the Pittsburgh area at exactly that time. His name appears in several civil records. Myers was a proven builder of armed barges, but he was getting on in years. Major Craig would have known of boats built by him previously. Lewis said he visited the boat every day, and that he spent most of his time with the workmen. He could not have done this if he stayed in Pittsburgh and the boat was more than fifteen miles away by water or over land in Elizabeth. As late as 3 August 1803, Lewis remarked in a letter to William Clark, then at present-day Louisville, Kentucky:

my boat only detains me, she is not yet compleated tho’ the work-man who contracted to build her promises that she shall be in readiness by the last of the next week. The water is low, this may retard, but shall not totally obstruct my progress being determined to proceed tho’ I should not be able to make greater speed than a boat’s length pr. day.[49]Lewis to Clark, 3 August 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 266; Jackson, ed., Letters 1:115-16.

On August 9th, Major Craig wrote to Caleb Swan that “Capt. Meriwether Lewis prepares to descend the Ohio and ascend the Mississippi.” Lewis wrote Jefferson another letter recounting in more detail some of his experiences during the last few weeks in Pittsburgh:

It was not until 7 O’Clock on the morning of the 31st Ultimo. that my boat was completed, she was instantly loaded, and at 10. A.M. on the same day I left Pittsburgh, where I had been moste shamefully detained by the unpardonable negligence of my boat-builder. On my arrival at Pittsburgh, my calculation was that the boat would be in readiness by the 5th of August; this term however elapsed and the boat so far from being finished was only partially planked on one side; in this situation I had determined to abandon the boat, and to purchase two or three perogues and descend the river in them, and depend on purchasing a boat as I descended, there being none to be had at Pittsburgh; from this resolution I was dissuaded first by the representations of the best informed merchants of that place who assured me that the chances were much against my being able to procure a boat below; and secondly by the positive assurances given me by the boat-builder that she would be ready on the last of the then ensuing week, (the 13th): however a few days after, according to his usual custom he got drunk, quarreled with his workmen, and several of them left him, nor could they be prevailed on to return: I threatened him with the penalty of his contract, and exacted a promise of greater sobriety in future which, he took care to perform with as little good faith, as he had his previous promises with regard to the boat, continuing to be constantly either drunk or sick. I spent most of my time with the workmen, alternately presuading and threatening, but neither threats, persuasion or any other means which I could devise were sufficient to procure the completion of the work sooner than the 31st of August; by which time the water was so low that those who pretended to be acquainted with the navigation of the river declared it impracticable to descend it; however in conformity to my previous determineation I set out,…[50]Lewis to Jefferson, Wheeling, 8 September 1803, Original ms in Bureau of Rolls-Jefferson Papers, series 2, vol. 51, doc. 102. Also reproduced in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 269; … Continue reading

In this letter, Lewis said that the boat was “completed” early in the morning of the 31st. If the massive and partly perishable supplies that had to be loaded on the boat just before leaving the dock had had to be loaded onto wagons at Fort Fayette, unloaded on docks located on the Monongahela River, and kept there exposed with quickly improvised stowage plans, this would have meant more delays, damage, and public speculation about the military nature of the expedition. Instead, Lewis stated explicitly that he loaded the boat on the very day it was completed and had it fully loaded three hours later.

The Right Man for the Job

Captains Lewis and Clark Departing for the Northwest Passage, 1804

32″ x 34″ oil on canvas

© 2009 by Charles Fritz. Used by permission.

A barge was the biggest vessel they could have used and still have gotten up the Missouri River. Just canoes and pirogues would be too small for the military supplies, trade goods, and other supplies that Lewis and Clark had to carry. Also, Lewis and Clark intended to take many more men and supplies out of St. Louis than were on the voyage down the Ohio. After more arduous river travel, Lewis wrote to Clark when he reached Cincinnati on 28 September 1803:

After the most tedious and laborious passage from Pittsburgh I have at length reached this place; it was not untill the 31st of August that I was enabled to take my departure from that place owing to the unpardonable negligence and inattention of the boat-builders who, unfortunately for me, were a set of most incorrigible drunkards, and with whom, neither threats, intreaties nor any other mode of treatment which I could devise had any effect; as an instance of their tardyness it may serfice to mention that they were twelve days in preparing my poles and oars.[51]Lewis to Clark from Cincinnati, 28 September 1803, Original ms in possession of Mrs. Julia Clark Voorhis and Miss Eleanor Glasgow Voorhis. Also in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 272; … Continue reading

Lewis referred to his builder in this letter as “a workman” and “the boat-builder” along with a set of “drunkards.” These references seem to rule out the possibility that he contracted with one of the bigger shipbuilding companies. Lewis noted that his boatbuilder was a man of “mature” years. Jacob Myers would have been about seventy and, given his long career, may have known many men in the area who were capable and willing to help with boatbuilding. Lewis does not, however, name Myers in his journal or letters. If a contract for the boat existed it is probable that the arrangements were made by Major Craig and Lieutenant Hooke. In his letters, Lewis stated several times that the boat had been “contracted for.” He did not say, however, that he himself had signed such a contract. Presumably, there was a contract made on paper, but this agreement would have been written and signed by Craig or Hooke as this was one of the duties that Major Craig had long exercised at Fort Fayette.

Although Lewis didn’t indicate the boatbuilder, he generously heaped complaints and insults upon him. At least some of the blame for the delay was due to the impossibly tight schedule. Also, the builder may have promised more than he could deliver in order to get the contract. So it is understandable why the boat was still in an early stage of construction on 15 July 1803. Had Lewis been successful in his original plan for having his big boat built on the Tennessee River, it could have been brought up to St. Louis in plenty of time for the Missouri expedition, with none of the struggles over the rapids of the Ohio River.

Judging by the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, however, this Pittsburgh boatbuilder was the right man for the job after all. Even a cursory reading of Lewis’ journal of his trip down the Ohio, in which the big boat was subjected to an amazing amount of abuse in being dragged over the rocks at many rapids, indicates that it is a wonder this boat made it as far as Cincinnati. This should also be a tribute to the design of the boat and its builder.

Conclusions

Captain Meriwether Lewis took his barge all the way from Pittsburgh to Camp River Dubois in 1803. In the spring of 1804, he and Captain William Clark took it all the way to Fort Mandan at the Knife River Villages in the far west, arriving in the fall. By spring 1805, the barge was reloaded and sailed down the Missouri River to St. Louis by some of his crew.

The success of these voyages is a remarkable testimony to Lewis and Clark and their men. But this success is also a testimony to the designers and builders of Lewis’ barge. Working in the heat and humidity on an impossible schedule, these men completed an incredibly durable vessel. They have been too long forgotten, and too often maligned.

The specific location of the building of this barge seems clearly to be Fort Fayette in Pittsburgh, not anywhere on the Monongahela River. The contractors were clearly Lieutenant Moses Hooke and Major Isaac Craig. Fort Fayette was their center of operations; Fort Fayette was where Lewis’ supplies were shipped and stored; and Fort Fayette was the location of the U.S. Wharf at the time. It was the only practical location at which the semi-secret project could be carried out.

When Larry Myers contacted the Heinz History Center in 2007, his communication led to a valuable reevaluation of the evidence that has accumulated about the building of the Lewis and Clark barge some two hundred years ago. Much of this evidence supports the conclusion that Jacob Myers was the principal builder of the Lewis barge.

Notes

| ↑1 | William K. Brunot, “The Building of the Barge: The Creation of the Lewis and Clark Flagship,” We Proceeded On, February 2022, Volume 48, No. 1. The full re=print is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol48no1.pdf#page=8.—KKT, ed. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Patricia Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” Pittsburgh Post Gazette Sunday Magazine, 3 August 2003; Leland D. Baldwin, The Keelboat Age on Western Waters (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1941; reprinted 1980). |

| ↑3 | Pierre Choteau in letter to William Henry Harrison, 22 May 1805, calls the Lewis boat “the barge of Capn. Lewis,” Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd. ed., 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978) 1:242. Choteau again calls it a “barge” in a letter to William Claiborne on 15 June, Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:248. Jefferson, in a letter to William Eustis on 25 June 1805, refers to “one of Capt. Lewis’s barges,” Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:249. |

| ↑4 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Definitive Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 vols. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:161-164.4. See also Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” |

| ↑5 | Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” |

| ↑6 | James Alton James, The Life of George Rogers Clark (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1928; reprinted St. Clair Shores, MI: Scholarly Press, 1970), 193. |

| ↑7 | Index, George Rogers Clark Illinois Regiment, Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Illinois, Sons of the Revolution in the State of Illinois, Record Number 6288-4-450-452, 21 July 1780. See also Record Number 6355-4-487-488 on Roll #4. |

| ↑8 | Ibid. Record Numbers 8363-5-354 and 8358-5-349. |

| ↑9 | Edgar Wakefield Hassler, Old Westmoreland: A History of Western Pennsylvania During the Revolution (Pittsburgh: J.R. Weldin & Company, 1900; reprinted Westminster, MD: Heritage Press, 1970), 131. |

| ↑10 | James, The Life of George Rogers Clark, 242. |

| ↑11 | George Rogers Clark Papers, Virginia State Library and Archives, The Illinois Regiment, Microfilm Reel #10, Record Number 14683-9-102-105. |

| ↑12 | Free & Accepted Masons, History of Lodge No. 45 F. & A.M. 1785-1910 (Pittsburgh: Press of Republic Bank Note Company, 1912), 93. |

| ↑13 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑14 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑15 | C. Hale Sipe, Fort Ligonier and Its Times (Harrisburg: The Telegraph Press, 1932), 627-29. |

| ↑16 | George Dallas Albert, Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania: Volume 2, The Frontier Forts of Western Pennsylvania (Harrisburg: Clarence M. Busch, State Printer of Pennsylvania, 1896), 130. |

| ↑17 | Sarepta C. Kussart, The Allegheny River (Pittsburgh: Burgum Printing Company, 1938), 32-37. |

| ↑18 | Paul David Nelson, Anthony Wayne: Soldier of the Early Republic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 228. |

| ↑19 | Leland D. Baldwin, Pittsburgh: The Story of a City 1750-1865 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1938), 108. |

| ↑20 | Letter from Major Isaac Craig to Secretary of War Henry Knox, 11 March 1792. Isaac Craig Papers 1768-1868, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh General Archival Collection, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. |

| ↑21 | Letter from Major Isaac Craig to Secretary of War Henry Knox, 30 November 1792, in Busch, Frontier Forts, 131. |

| ↑22 | Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., Original Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1905), 1:xxvii. |

| ↑23 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑24 | Mark Welchley, “Ohio Packet Boats,” Milestones, 7:2 (Spring 1982) accessed at www.bcpahistory.org. |

| ↑25 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑26 | Baldwin, Pittsburgh, 140,141. |

| ↑27 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑28 | Fred Anderson, Crucible of War: The Seven Years’ War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766 (New York: Alfred E Knopf, 2000), 103–4. |

| ↑29 | Robert Wellford, “A Diary Kept by Dr. Robert Wellford, of Fredericksburg, Virginia, during the March of the Virginia Troops to Fort Pitt (Pittsburg) to Suppress the Whiskey Insurrection in 1794.” The William and Mary Quarterly 11, no. 1 (1902): p. 7, accessed 24 November 2022 from doi.org/10.2307/1915481. |

| ↑30 | Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, 1:xxv. |

| ↑31 | Baldwin, Pittsburgh, 124-28. |

| ↑32 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑33 | Baldwin, Keelboat Age. |

| ↑34 | Lowry, “Who Built the Big Boat?” |

| ↑35 | Kussart, The Allegheny River, 33. |

| ↑36 | See Craig’s note of Sept. 15, 1800, Craig Papers, AA/Craig/VII; Abstract of Forage, Sept. 9, 1800, AA/Craig/V.c; also VII.e, Sept 15, 1800. See John Bakeless, Lewis & Clark, Partners in Discovery (New York: William Morrow & Company, 1947), 469. |

| ↑37 | Richard Dillon, Meriwether Lewis: A Biography (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1965; reprinted Lafayette, CA: Great West Books, 2003), 25. |

| ↑38 | Lewis’ receipt to Isaac Craig, 22 March 1801. Receipt Book, Craig Papers; Account Book, Craig Papers, AA/Craig/IIIc. There are various references to Lewis in these papers. See Bakeless, Lewis & Clark, 469. |

| ↑39 | Thwaites, Original Journals, Appendix, 210. Also see “Articles Purchased for the Expedition,” in Frank Bergon, ed., Journals of Lewis and Clark (New York: Penguin Books, 1989), xxxvi. Lewis told Thomas Rodney later that his boat had cost $400. |

| ↑40 | Lewis to Jefferson, from Philadelphia, 20 April 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 214; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:38. |

| ↑41 | Lewis to Jefferson, from Philadelphia, 29 May 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 214; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:53. |

| ↑42 | Lewis to Jefferson, 26 July 1803. Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 264-65; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:113-14. |

| ↑43 | Lewis to Jefferson, 26 July 1803. Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix 264-65; Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:113-14. |

| ↑44 | Bergon, Journals of Lewis and Clark, xliv. |

| ↑45 | Bergon, Journals of Lewis and Clark, xliv. |

| ↑46 | Lewis to Jefferson, 15 July 1803, in Jackson, ed., Letters, 1:110. |

| ↑47 | The post office was at Front and Ferry streets. See item 37 in Lois Mulkern, “Pittsburgh in 1806,” Pitt: A Quarterly of Fact and Thought at the University of Pittsburgh, Spring 1948; also at digital.library.pitt.edu/pittsburgh/beck/. |

| ↑48 | Lewis to Jefferson, Pittsburgh, 22 July 1803. Original ms in the Bureau of Rolls: Jefferson Papers, series 2, vol. 51, doc. 100. Reproduced in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 260; Jackson, ed., Letters 1:111-12. |

| ↑49 | Lewis to Clark, 3 August 1803, Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 266; Jackson, ed., Letters 1:115-16. |

| ↑50 | Lewis to Jefferson, Wheeling, 8 September 1803, Original ms in Bureau of Rolls-Jefferson Papers, series 2, vol. 51, doc. 102. Also reproduced in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 269; Jackson, ed., Letters 1:121-22. |

| ↑51 | Lewis to Clark from Cincinnati, 28 September 1803, Original ms in possession of Mrs. Julia Clark Voorhis and Miss Eleanor Glasgow Voorhis. Also in Thwaites, ed., Original Journals, Appendix, 272; Jackson, ed., Letters 1:124-25. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.