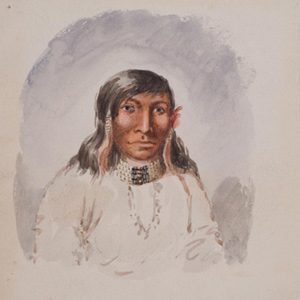

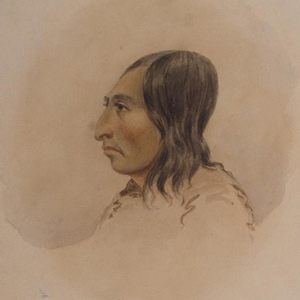

Self-Portrait (c. 1848)

by Paul Kane (1810–1871)

Oil on paper, 8 1/8 x 6 11/16 inches (20.6 x 17 cm). Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, Bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, collections.starkculturalvenues.org/objects/42773/selfportrait?ctx=c9bd272f-d876-4171-b778-1ab5e0b60c91&idx=19.

Paul Kane (1810–1871) painted in the Canadian Northwest which then included the Hudson’s Bay Columbia District. His field sketches, notes, and paintings are a valuable resource for ethnologists. His autobiographical 1859 Wanderings of an Artists Among the Indians of North America—available at https://archive.org—also provides useful information.

Pages with Paul Kane’s Art

The Palouses

At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Palouses had coalesced around four primary villages on the lower Snake River: Penewawa, Almota, Wawaiwai, and Palus. Lewis and Clark estimated their population as 2,300 which included Northern Nez Perce.

April 6, 1806

Into the Columbia River Gorge

The members pack up the last of the dried meat and paddle into the Columbia River Gorge. Lewis remarks on the spring flood, a ‘remarkable’ Beacon Rock, and the blindness common with the local People.

The life and times of these three explorers intertwined in a number of odd and interesting ways, often brought together by far-reaching hand of Thomas Jefferson. Tracing these connections opens a window onto every conceivable aspect of the period.

Concomly was a prominent Chinook citizen and leader whose people lived on the north side of the Columbia estuary, on the shore of Haley’s Bay. On November 17, 1805, he introduced himself to Lewis and Clark at Station Camp.

The Nez Perce

by Kristopher K. Townsend

First encountered September 1805 when John Colter met them on Lolo Creek near Travelers’ Rest, they would remain with the expedition in one way or another until 25 October 1805 saying their goodbyes at Rock Fort at The Dalles of the Columbia River. They were together again between 23 April 1806 and 4 July 1806, the expedition’s longest period of contact with any Native American Nation.

The Walla Wallas

Walla Wallas, sometimes Waluulapam and sometimes on this site as Walula, are a Sahaptin-speaking indigenous people that lived primarily along their namesake river. There has been disagreement among historians regarding the nation’s etymology.

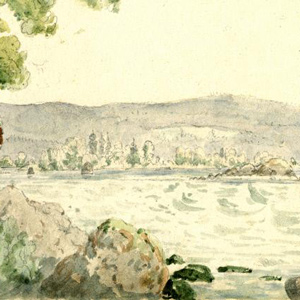

Here the Columbia was “an agitated gut Swelling, boiling & whirling in every direction.” Even so, Cruzatte and Clark agreed that they could run the canoes through.

The Clatsops

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The creek where Coyote built his legendary house—today’s Neacoxie Creek—flows north to south bisecting nearly the length of the Clatsop Plain. A village at the estuary created by the ocean, Neacoxie Creek and the larger Necanicum River is Ne-ah-coxie Village. Nearby were three other Clatsop villages, and for a short time, a salt works built by soldiers from the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

April 3, 1806

Mapping the Willamette River

Clark concludes his exploration of the Willamette River and learns that a smallpox epidemic had devastated the local population. At Provision Camp, Lewis demonstrates the air gun as a defensive measure.

November 1, 1805

A day with the Watlalas

Most of the men move baggage and canoes around the Cascades of the Columbia. Clark describes the Upper Chinookan Watlala People living in the area, and Lewis adds Pacific madrone to his plant collection.

The Clackamases

by Kristopher K. Townsend

The Clackamas people had about twelve villages south of the Columbia River, along the Clackamas River, and at Willamette Falls in what is now Portland and Oregon City. They spoke the Clackamas dialect as did nearby Multnomahs and Skilloots. On 2 April 1806, two young Clackamas men came to “Provision Camp” near present-day Washougal and sketched a map of the Willamette River, the mouth of which the expedition captains had failed to find.

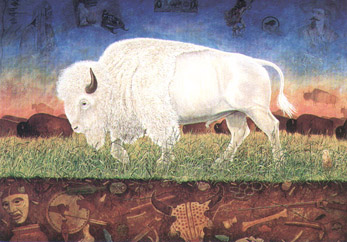

Bison Gallery

Art featuring the iconic buffalo

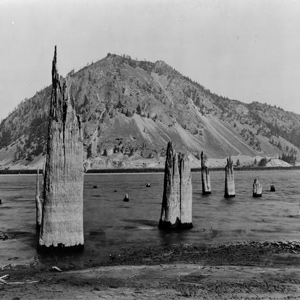

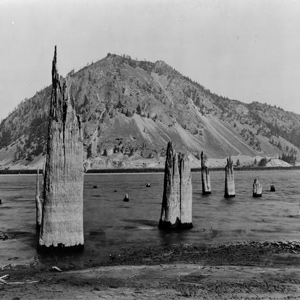

A Submerged Forest

by John W. Jengo

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.

October 31, 1805

Portaging the "Great Shute"

Clark and Pvt. Cruzatte scout the “Great Shute” at the Cascades of the Columbia, and two canoes are carried around the rapids. Clark continues down the river and sees a tall monolith—Beacon Rock.

October 27, 1805

Sahaptin v. Chinookan

Sgt. Gass notices visitors with flattened heads, and the captains compare languages and customs of the Sahaptin and Chinookan Peoples living above and below The Dalles of the Columbia.

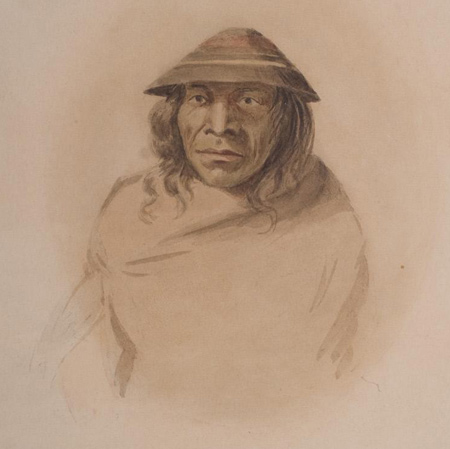

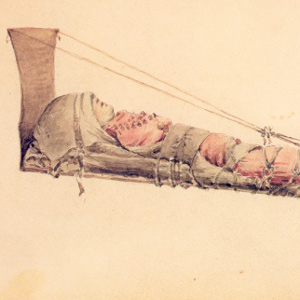

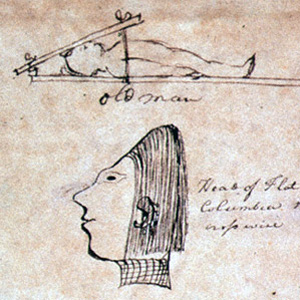

The most remarkable trait in the Clatsop Indian physiognomy, Lewis wrote on 19 March 1806, was the flatness and width of their foreheads, which they artificially created by compressing the heads of their infants, particularly girls, between two boards.

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.