History

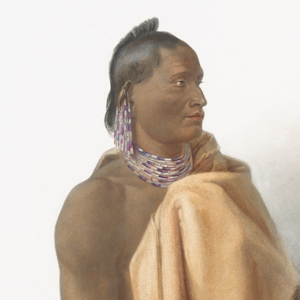

Mássika (Sauk) and Wakusásse (Fox)

Karl Bodmer (1809–1893)

Courtesy New York Public Library Digital Collections[1]Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Mássika, Sáki Indianer. Mássika, Indien Saki. Mássika, Saki Indian; Wakusásse, Musquake Indianer. Wakusásse, Indien Musquake (Renard). … Continue reading

To outsiders in 1803, the Sauk and Fox people living on the Mississippi River in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin were seen as one people.[2]Moulton, Journals, 2:181n1. They were a close alliance, not a single tribe, but were nevertheless given United States federal recognition as the Sac and Fox. Further distinctions emerged as the alliance changed and today, there are three federally recognized Sac and Fox tribes.

At time of European contact, the Fox were living on the Wolf River in present-day Wisconsin having migrated there from Michigan and perhaps Northwest Ohio to avoid the invasive Iroqouis. The Sauk migrated to the Green Bay area during the Iroqouis incursions, but their post-contact migration patterns often differed from the Fox.

Both peoples spoke the Sauk-Fox-Kickapoo dialect of Algonquian and had similar cultures and economies. Both combined hunting with horticulture and gathering. They also traded furs and mined lead.[3]Charles Callender, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 636–672.

Black Hawk

Múk-a-tah-mish-o-káh-kaik, Black Hawk, Prominent Sac Chief

George Catlin (1796–1872)

Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum. Public domain.

About Black Hawk, Catlin wrote:

This man, whose name has carried a sort of terror through the country where it has been sounded, has been distinguished as a speaker or counsellor rather than as a warrior . . . . When I painted this chief, he was dressed in a plain suit of buckskin, with strings of wampum in his ears and on his neck, and held in his hand his medicine-bag, which was the skin of a black hawk, from which he had taken his name, and the tail of which made him a fan . . . .[4]George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, reprint (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1926) 2:239.

While the Lewis and Clark expedition struggled up the Missouri River in 1804, the new territorial governor of Indiana, William Henry Harrison, negotiated a treaty with the Sauk and Fox ceding their lands east of the Mississippi for goods and an annual annuity. The treaty was quickly disputed as not being authorized by the whole of the Potawatomis. The dispute led to a political split among the Sauk.

In 1832, a brief war, the Black Hawk War, was fought by those who still did not accept the original 1804 treaty. Throughout the conflict, William Clark was Superintendent of Indian Affairs and sought ways to prevent violence. Despite those efforts, the war ended in tragedy for the Sauk with heavy casualties. Only a small group of Sauk residing in Iowa participated in the war, but all of them were seen as guilty and forced to cede more of their lands. Black Hawk and two others were imprisoned at Jefferson Barracks, and Clark successfully lobbied for their released. [5]This simple version of the Black Hawk War is more fully explained in Jay Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), chapter 7 and Callender, 651–653.

Toponymy

The Fox name for themselves is Meskwaki meaning Red-Earths. Their current English name was translated from the French renard, the name of one of their groups or clans that was mistakenly applied to the entire people. In the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” they are listed as “Renars or Foxes.”

Fox: Renard, Renarz, Renars or Foxes

Meskwaki: Meshkwahkihaki, Mechecaukis, Mechecouakis, Meskwaki, Mesquakie, Mesquaki, Miscouaguis, Misquachki, Muskwaki, Musquakies

The Sauk call themselves Asaki-waki (asa•ki•waki). Their common name was derived from the French forms of an Algonquian word.

Sauk: Sac and Saki with variants Sachi, Satzi, Saquis, Saugies, Saukeas, Sakes, Sawkeys, Sacks, Saxes.

Expedition journalists used these spellings: Sauckee, Saukee, O Sau-kee. On 20 June 1804, Clark spells the town of Sauk Prairie as Saukee Prairie.[6]Callender, 645–646, 654–655.

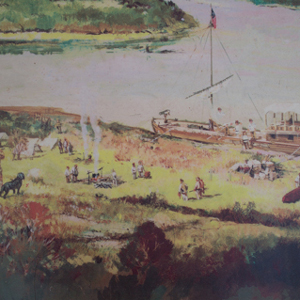

Selected Encounters

March 12, 1804

St. Louis speech

In St. Louis, Dehault Delassus delivers a speech to several Indians informing them of the transfer of Upper Louisiana from Spain to the United States. Meriwether Lewis witnesses the event.

March 25, 1804

Bad mosquitoes

Men collect honey and complete various errands around winter camp at the River Dubois—present Wood River. Clark orders food for two dozen Sauk Indians and reports that the mosquitoes are bad.

May 5, 1804

Sauk and Kickapoo visitors

In St. Louis, Lewis prepares for departure up the Missouri River. Across the Mississippi at Camp River Dubois, Clark receives Sauk and Kickapoo visitors.

May 17, 1804

St. Charles court martial

Privates Hugh Hall and John Collins misbehaved in St. Charles the previous night and today face a court martial. Some visiting Kickapoos tell Clark that the Sauk and Osage are at war—a thing the captains have been trying to prevent.

June 5, 1804

Passing the Manitou

South of present Lupus, Missouri, the enlisted men and engagés struggle to move the boats past sandbars and channels clogged with driftwood. Ordway interprets a pictograph of a Manitou as a devil.

June 13, 1804

The mouth of the Grand

The expedition travels nine miles up the Missouri River passing sandbars, shoals, and an abandoned Missouria village. They camp at the mouth of the Grand where Clark and Lewis take lunar observations.

June 15, 1804

Dangerous Missouri river

The men struggle to move the boats against the strong Missouri current with submerged logs and crumbling banks. They camp opposite old Little Osage and Missouria villages at present Malta Bend.

June 17, 1804

Rope Walk Camp

Near a traditional river crossing and present-day Waverly, Missouri, the expedition stops to make new rope and oars. The French engagés ask for more food, and several men suffer from boils and dysentery.

June 20, 1804

York is injured

Whitehouse reports hard rowing and Ordway notices crab apple trees as they work their way to a camp near present Lexington, Missouri. York is injured when one of the men throws sand in his eyes.

June 28, 1804

The Kansa people

The expedition remains another day at the mouth of the Kansas where Lewis determines its latitude. Lewis describes the river and Clark describes the Kansa People.

Notes

| ↑1 | Rare Book Division, The New York Public Library. “Mássika, Sáki Indianer. Mássika, Indien Saki. Mássika, Saki Indian; Wakusásse, Musquake Indianer. Wakusásse, Indien Musquake (Renard). Wakusásse, Musquake Indian.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed February 3, 2019. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-c428-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Moulton, Journals, 2:181n1. |

| ↑3 | Charles Callender, Handbook of North American Indians: Northeast Vol. 15, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978), 636–672. |

| ↑4 | George Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians, reprint (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1926) 2:239. |

| ↑5 | This simple version of the Black Hawk War is more fully explained in Jay Buckley, William Clark: Indian Diplomat (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), chapter 7 and Callender, 651–653. |

| ↑6 | Callender, 645–646, 654–655. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.