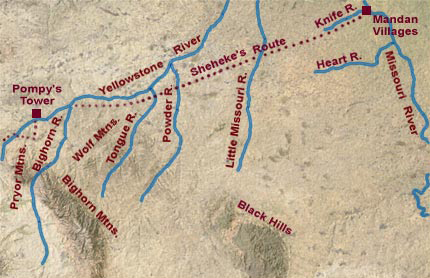

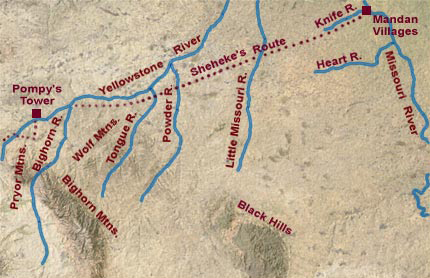

Pryor’s mission was to take the horses to the Knife River Villages and then on to Fort Assiniboine to deliver a letter to Hugh Heney.

Two Letters

Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone

To see labels, point to the photo.

© 1998 by Larry Mayer. All rights reserved.

On 24 July 1806, Clark described this area while waiting for Pryor to catch up with the horses. In the photo above, the view is toward the southwest. On the horizon is the Beartooth Range, which include the highest mountain in Montana, 12,709-foot Granite Peak. Three miles up the Yellowstone, just out of the picture at upper right, is the town of Laurel, Montana; 25 miles downriver, below the photo, is the city of Billings.

Sergeant Nathaniel Pryor had been told of his mission sometime earlier, perhaps back at Travelers’ Rest. But it was on 23 July 1806, the day before Clark’s contingent shoved off from their Canoe Camp on the north bank of the Yellowstone near today’s Park City, Montana, that Clark handed him his written orders, along with the letter to Hugh Heney. The letters are in Clark’s handwriting, but the wording and spelling are clearly in Lewis’s style:

Camp on the River Rochejhone 115 Miles

below the Rocky Mountains July 25th [23rd] 1806Sir:

You will with George Shannon, George Gibson & Richard Windser [Windsor] take the horses which we have brought with us to the Mandans Village on the Missouri. When you arrive at the Mandans, you will enquire of Mr. Jussomme [René Jusseaume] and any british Traders who may be in neighbourhood of this place for Mr. Hugh Heney. If you are informed, or have reasons to believe that he still remains at the establishments on the Assinniboin River, you will hire a pilot to conduct you and proceed on to those establishments and deliver Mr. Heney the letter which is directed to him. You will take with you to the Establishments on the Assinniboin River 12 or 14 horses, 3 of which Mr. Heney is to have choise if he agrees to engage in the Mission proposed to him.

In his written order, Clark also provided Pryor with a shopping list: “As maney of the remaining horses as may be necessary you will barter with the traders for such articles as we may stand in need of . . . .”

Clark’s Shopping List

flints

3 or 4 dozen knives

a few pounds of paint[1]Paint pigment was sold by the pound. The first ready-mixed paint was patented in the U.S. in 1867. The captains may have intended to paint marks on the canoes to make them easier to identify from a … Continue reading

pepper

sugar

coffee or tea

2 dozen coarse handkerchiefs

2 small kegs of spirits

2 capotes[2]Long, hooded cloaks or coats—either for the captains or else for sentries during cool nights.

tobacco

glauber salts[3]This item suggests the general condition of the men’s health at this point, possibly because of the imbalances in their diet. Glauber’s Salts, or Sal Glauber, is a mild laxative. Gary … Continue reading

“such curious species of fur as you may see”

Clark’s list tells us something about how the Corps of Discovery was faring, as far as supplies were concerned, after more than two years on the trail. Of these items, Clark lists three top priorities: tobacco, knives, and flints.[4]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:131.

At Clark’s Fork

Clark and his contingent arrived here early in the morning, an estimated twenty-nine miles downstream from the Canoe Camp, and indicated in his courses and distances for that date that he believed it was the Bighorn River.[5]Gary Moulton, ed., TheJournals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 8:221n.

This . . . River is 150 yards wide at it’s Mouth and 100 a Short destance up. The water of a light Muddy Colour, and much Colder than that of the Rochejhone. A Small island is Situated imediately in its mouth.

Apparently he reviewed his Yellowstone River journey when he visited with the Mandans and Hidatsas again in mid-August 1806, and was told this was the river they called “The Lodge Where All Dance”—perhaps actually a reference to the “old Indian fort of logs and bark” some six miles farther downriver, that Shannon had noticed as they passed by:

This Lodge, a council lodge. It is of a Conocil form 60 feet [in] diamuter at its base built of 20 poles, each pole 2-1/2 feet in Secumpheranc and 45t feet Long . . . & covered with bushes. In this Lodge I observed a Cedar bush Sticking up on the opposit side of the lodge fronting the dore. On one side was a Buffalow head, and on the other Several Sticks bent and Stuck in the ground. A Stuffed Buffalow skin was Suspended from the Center with the back down. On the top of those poles were deckerated with feathers of the Eagle & Calumet Eagle, also Several Curious pieces of wood bent in Circleler form with sticks across them in form of a Griddle hung on tops of the lodge poles, others in form of a large Sturrip.

He later told Biddle that he considered this a good place for a trading post because the beaver country began here.

Pryor’s Journal

Pryor was also instructed to keep a journal, including “courses, distances, water courses, Soil production, & animals to be particularly noted.” Unfortunately, no such journal is known to exist today; reportedly it was lost in shipment to France for publication.

Personnel Changes

The following morning, assisted by Privates George Shannon and Richard Windsor, Pryor was to take their remaining seventeen horses to the Mandan villages. At the outset, Private George Gibson was to have been part of Pryor’s detail, but he had not sufficiently recovered from his accident on 18 July 1806, and the sergeant had set out with only two helpers, Privates George Shannon and Richard Windsor. But before the end of the first day of his mission, he found that even with only seventeen horses to drive, he would need more help. Some of the animals were stronger and faster than others, and every time they came upon a herd of bison the leaders would race ahead to circle them up, as the horses’ original Indian masters had trained them to do. The best solution seemed to be to send one man ahead to try to haze the big bovines out of the way, and for that Pryor needed an extra hand or two. So Clark assigned him Hugh Hall, a non-swimmer who perhaps had been nervously hoping for some excuse to get out of those tippy canoes.[6]Clark, 24 July 1806.

More About Pryor’s Mission

August 8, 1806

Sgt. Pryor catches up

In the morning, Pryor arrives at Clark’s camp having paddled two bull boats down the Yellowstone River. Lewis sets up a camp near present-day Williston to make clothes, repair boats, hunt, and make jerky.

July 20, 1806

Hopes dim and rise

Lewis sees the Marias watershed and hopes for extending the Louisiana Territory dim. Clark builds dugouts on the Yellowstone and hopes Hugh Heney will accept a commission. Ordway and Gass are at the Falls of the Missouri.

Pryor was assigned several special missions from exploring the Sandy River to escorting Mandan Chiefs to Washington City. He would barely survive his adventures on the Yellowstone River.

While stinging from having so many of his horses stolen, Clark wrote a speech to the Crow Indians imploring them to return the booty. After all, he needed those horses to complete the captain’s bold diplomatic plan.

Pryor Creek begins in the Pryor Mountains 50 miles from its mouth, but coils into nearly 100 miles of creek bottom by the time it empties into the Yellowstone. Local lore maintains that Pryor traveled up this creek to those mountains.

There was no Northwest Passage by water; and the portage they found took much longer than a day. The political repercussions from that alone could be immensely embarrassing to Jefferson. Something had to be done….

August 6, 1806

Pryor takes Clark's note

On or near this date, Pryor takes Clark’s note meant for Lewis delaying the captains’ reunion. Near present Williston, Clark moves very little as he waits for Lewis who passes the Poplar River on this day.

Indians stole all the horses, so Sgt. Pryor and his three privates constructed two bull boats and floated down the Yellowstone River in hopes of catching up with Clark or Lewis.

Via the shorter route, Pryor would have arrived at the Knife River villages by about 6 August 1806. A trip to see Hugh Heney at Fort Assiniboine would take another two weeks.

Pryor was to proceed downriver to the mouth of the Bighorn River, where Clark, with the canoes, would help him and his detail across the Yellowstone to its south bank. But they happened upon a good fording place at today’s Billings, and seized the opportunity.

Pryor and six privates had successfully driven forty-one horses all the way to the Yellowstone Valley, apparently without any trouble. Then, smoke on the horizon. Twenty-four horses stolen on the twentieth. Seventeen taken on the twenty-fifth.

Notes

| ↑1 | Paint pigment was sold by the pound. The first ready-mixed paint was patented in the U.S. in 1867. The captains may have intended to paint marks on the canoes to make them easier to identify from a distance. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Long, hooded cloaks or coats—either for the captains or else for sentries during cool nights. |

| ↑3 | This item suggests the general condition of the men’s health at this point, possibly because of the imbalances in their diet. Glauber’s Salts, or Sal Glauber, is a mild laxative. Gary Lentz, “Meriwether Lewis’s Medicine Chests,” We Proceeded On, Vol. 26, No. 2 (May 2000), 10–17. |

| ↑4 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:131. |

| ↑5 | Gary Moulton, ed., TheJournals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 8:221n. |

| ↑6 | Clark, 24 July 1806. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.