Gloomy Aspect

Nothing can be imagined more tremendous than the frowning

darkness of these rocks,

which project over the river

and menace us with destruction.

Lewis’s Impressions

a most sublime and extraordinary spectacle

we called the Gates of the Mountains

During the day, in this confined valley through which we are

passing, the heat is almost insupportable; yet, whenever we

obtain a glimpse of the lofty tops of the mountains,

we are tantalized with a view of the snow.

Late in the day on 19 July 1805, Lewis and his party entered a canyon between “the most remarkable clifts that we have yet seen.” They seemed to rise “from the waters edge on either side perpendicularly to the hight of 1200 feet. the tow[er]ing and projecting rocks in many places seem ready to tumble on us.” The entire scene wore “a dark and gloomy aspect.” The rock looked to him like “black grannite below and . . . of a much lighter colour above and from the fragments I take it to be flint of a yelloish brown and light creemcolourd yellow.” They arrived at the most imposing place at the eleventh course of the day—18¼ miles into a 22-mile travel day—and the gathering shadows at water level lent the effect of blackness to the rocks in the depths of the canyon, while the peaks and ridges nearly 2,000 feet above the river toward the east were still tinged with the reddening light of the setting sun. But it was “late in the evening”—afternoon, we would say—when he entered the canyon, and he was compelled to continue until sometime after dark before he found a place on the bank with enough room and sufficient firewood for the night’s camp.

It seemed to Lewis that the river appeared to have “forced it’s way through this immence body of solid rock for the distance of 5¾ miles.” That is true, but the geological picture is somewhat more complex than that. The dominant rock formation in the Gates is the Mississippian-age Mission Canyon Formation of the Madison Group, but there is a large exposure, about one mile long, of the Lodgepole Formation, also of the Madison Group, on the right cliffs near the lower end of the Gates. At about the middle of the Gates on both sides, and most obviously at Fields Gulch, are exposures of the Kibbey Formation (Mississippian) and the Heath and Otter Formations. These three latter formations are less resistant to erosion than the limestones of the Madison Group, and that is why the Gates are lower near the river in that area. (See photo: “Gates . . . From the Air—View North, Downstream.”) In the geologic time scale as understood today, the period called Mississippian extended from 360 to 320 million years ago. The Madison Group, according to the latest chronologies, was deposited about 330 to 345 mya.

Even the few advanced students of geology in Lewis’s generation would have been unable to comprehend that timescale, much less the nomenclature now used to describe it. Nevertheless, “from the singular appearance of this place,” Lewis wrote, he called it “the gates of the rocky mountains.” (This is one of only 17 place names that have survived from the 128 they inscribed on their maps of what is now Montana.) Sergeant Ordway’s reaction was more reserved than Lewis’s. This was “a curious looking place.”

Lewis and the rest of the men continued to look for wildlife. As expected, they had seen no buffalo since entering the mountains, but today they “saw some Bighorns [bighorn sheep] and a few Antelopes [pronghorn] also beaver and Otter.” By the time they reached the canyon, however, the light was probably too dim for the explorers to notice any of the Indian pictographs that are still faintly visible along the river today—if those were even there then.

Three Aerial Views

Aerial photographer Jim Wark shot this view southward from above Mann Gulch, which was the scene of a forest wildfire in 1949 that overran and killed a crew of 13 smokejumpers who had been dropped into the steep, remote terrain. Upper Holter Lake and Hilger Valley are beyond the Gates at upper center and right. On the horizon, at right beneath the cloud bank, is Mount Haggin (el. 10665 ft.), nearly 80 miles away at the north end of the Anaconda Range.

This view from Jim Wark’s Christen A-1 Husky—a single-engine, high-wing, bush-type airplane—is aimed a few degrees east of north. The labels (including the misspellings) were applied to the gulches and canyons nearly a century after the Corps of Discovery passed through the Gates of the Mountains without naming anything else. Although primitive camping is not prohibited anywhere along the river, except in the day-use area at the mouth of Meriwether Gulch, it is no easier to find a place to get out of the river than it was for Lewis, who complained “it is deep from side to side nor is ther in the 1st 3 miles of this distance a spot except one of a few yards in extent on which a man could rest the soal of his foot.” Besides, the Gates of the Mountains is so popular with boaters that few campers get much sleep, what with voices and motor noises bouncing off the cliffs and across the water until well after midnight. Lewis and his contingent at least got a good night’s rest.

The location of Lewis’s campsite for the night of 19 July 1805 is not certain. His “courses and distances” for that day suggest that his camp was approximately a mile farther south than Clark shows it on his map. Robert Bergantino’s research has produced two possible sites, which are indicated in the aerial photographs immediately above and below. His first choice is “Camp (A)” at 46°50’05″N 111°55’35″W; his second choice is “Camp (B)” at 46°50’17″N 111°55’24″W.[1]Although the end of Lewis’s thirteenth and last Course for 19 July can be identified with a high degree of confidence, his final remark leaves much room for interpretation: “a little … Continue reading Both sites, however have been under water since Holter Dam raised the level of the river to an average depth within the Gates of 25 to 30 feet.

Here we see the lower (downstream) end of placid Upper Holter Lake, with American Bar at lower right—its size before Holter Dam created the lake here revealed by the lighter tint—and the Gates of the Mountains sliced through the northwest end of the Big Belt Mountains. The white specks on the water are tour boats and pleasure craft, many of which dock at the marina at lower left. At upper extreme left the lake-river winds northwest toward Holter Dam, 22 miles from the outlet of Upper Holter Lake.

Anton M. Holter (1831-1921), said to have been the first native Norwegian to settle in Montana Territory, was one of early Montana’s most successful entrepreneurs. At Alder Gulch he designed and built the first planing mill in the Territory, to produce finished lumber. He arrived in the vicinity of Helena in 1864 and, relying on his own ingenuity and optimism, soon amassed a large fortune and its accompanying influence. His commercial empire, which eventually extended as far away as Idaho and British Columbia, consisted of mining companies and related industries, lumber and hardware operations both wholesale and retail, railroads and hydroelectric developments—in 1918, with Congressional authorization, he built Holter Dam.[2]Kenneth Bjork, “Norwegian Gold Seekers in the Rockies,” Norwegian-American Studies, Volume 17 (1952), p. 47 and following. http://www.naha.stolaf.edu/pubs/nas/volume17new/vol17_3.html. … Continue reading In all, he founded 46 companies during his lifetime, and also exercised his civic leadership by serving as the first Republican state senator, and as the mayor of Helena. Helena’s Holter Museum of Art, founded in 1987, is a fitting memorial to the man. It was individuals such as Anton Holter who ultimately “opened” the West.

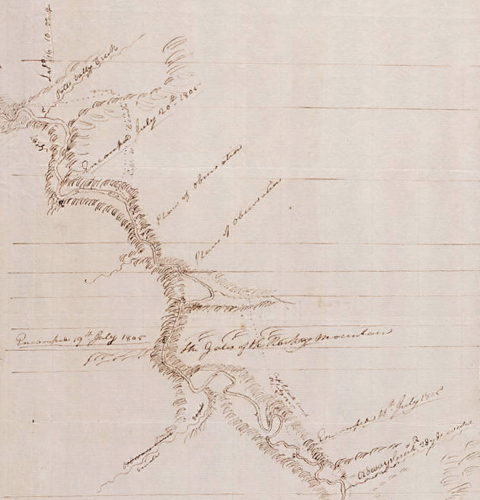

Clark’s Journey

The two captains, “anxious now to meet with the Sosonees or Snake Indians as soon as possible in order to obtain information relative to the geography of the country,” agreed on 18 July 1805 that Clark should “take a small party & proceed on up the river, some distance ahead of the canoes,” so that the hunters’ guns wouldn’t frighten the Indians away. With York, Joseph Field and John Potts, he left the river in the vicinity of Holter Dam, proceeded southeast to Falls Gulch, then up it to the Beartooth Mountain divide where he camped—possibly within view of the The Bears Tooth landmark, though he said nothing of it in his journal. They then descended Towhead Gulch to Hilger Valley, thence back to the river.

Clark missed the sublime experience of navigating through the Gates of the Mountains. Beyond the cliffs to the west, he and his detail were suffering from blistered feet, worsened by prickly pear cactus spines and sharp “flint” rocks. Their discomfort was overshadowed, however, by the plentiful signs that Indians were, or had been, nearby, and the Americans readily convinced themselves those would be Shoshone.

One of those signs was the smoke Clark saw up “Potts Vally Creek” [Big Prickly Pear Creek]:

The Cause of this Smoke I can’t account for certainly tho’ think it probable that the Indians have heard the Shooting of the Partey below and Set the Praries or Valey on fire to allarm their Camps; Supposeing our party to be a war party comeing against them. I left Signs to Shew the Indians . . . that we were not their enemeys.

The circle at the mouth of “Potts Vally Creek” calls attention to the symbol he used to represent that smoke.

The significance of the horizontal lines is hard to determine. They might have been intended as guidelines, but they are at varying distances from each other, and seem to have little to do with the points identified in this sketch. Their presence may be purely coincidental.

In general, Clark used a variable scale for his sketches. Most are at about six inches to the mile; a few are at four inches to the mile. On some sketches the scale changes abruptly, as if according to whim—up to eight inches to the mile or as little as two. His sketch maps merely were meant to be guides to the relative placement of important points and objects, and all should have been re-drafted upon the expedition’s return, just as the astronomical observations should have been recalculated.

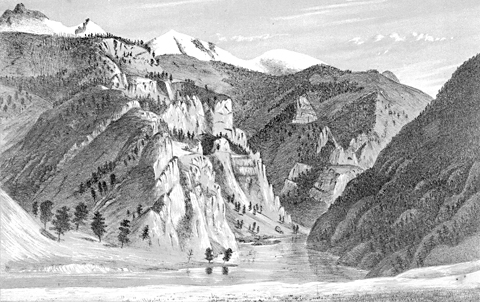

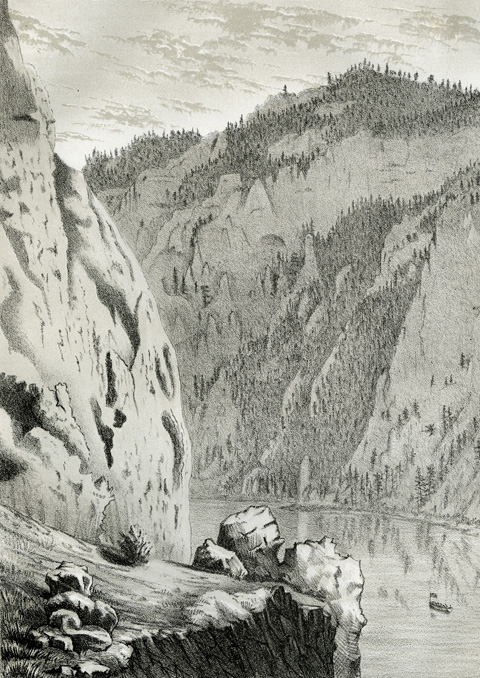

Mathew’s View

Of all objects of interest to be found in Montana, at least all that the author has seen, he is inclined to give the palm to the Gate of the Mountains. It is no doubt superior to anything in the way of a canyon to be found in the entire western country. Here the Missouri has forced a channel through a lofty range of mountains, that form massive walls on each side of nearly one thousand feet in perpendicular height. Beyond the immense walls the mountains reach up into the heavens two thousand feet higher—their summits often covered with snow. The scenery is of such surpassing grandeur as to defy description. Plate XVII is a view just below American Bar, looking down [the Missouri]; and plate XVIII is a view from below looking up.

—Alfred E. Mathews, Pencil Sketches of Montana (New York: By the Author, 1868), 84-85.

Tourist Attraction

“The Heart of the Gates of the Rocky Mountains”

From a painting by Ralph DeCamp

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”

Olin D. Wheeler was a writer and publicist for the Northern Pacific Railway, which parallels much of the Lewis and Clark Trail, especially from Billings westward. His highly successful book, illustrated with more than 100 halftones mostly made from pictures taken by photographers he hired along the route, gave the American public its first comprehensive view of the trail, on the occasion of the centennial observance of the expedition.

Ralph DeCamp was a minor American painter who was living in Helena, Montana, around 1900. He later became associated with a group of ten Impressionist painters that included several more prominent figures such as Childe Hassam, John Henry Twachtman, J. Alden Weir, and William Merritt Chase. In 1902 DeCamp accompanied Olin D. Wheeler over segments of the Lewis and Clark trail not only as an artist but also as a photographer.

Undoubtedly it was Nicholas Biddle’s eloquent description of the Gates of the Rocky Mountains that aroused and maintained its wide public appeal. The railroad survey expedition led by Isaac Stevens explored the area a decade before the discovery of gold in Last Chance Gulch, and one of the party’s artists, John Mix Stanley, painted a picture of one of its principal features, the Bears Tooth. Alfred E. Mathews followed in the mid-1860s with two pencil sketches of the canyon to tantalize urban easterners with nature’s grandeur.

The pleasure-cruises of the Gates of the Mountains today owe their beginning to another important settler who arrived in the Helena valley at about the same time as Anton Holter. He was Nicholas Hilger,[3]Undaunted Stewardship, http://m.helenair.com/news/local/sieben-hilger-ranches-to-get-stewardship-interpretive-displays/article_905ae146-1491-5d9a-baa6-08b2a40f805e.html. Accessed June 2015. Undaunted … Continue reading who became a widely respected Judge, Justice of the Peace, and rancher. In 1886 Hilger ordered a steel-hulled steamboat, 55 feet long and ten feet wide, from a company in Dubuque, Iowa. The $4,800 stern-wheeler was shipped in two sections over the Northern Pacific Railroad to Townsend, 35 miles south of Helena, where the two sections were riveted together. The “Rose of Helena” steamed down the Missouri to Hilger’s ranch at the mouth of Hilger Valley, and immediately was put into service as a sight-seeing boat. On 10 May 1887, the Rose was the vehicle for the greatest local adventure of the decade. Setting out from Hilger’s ranch, the Rose headed downriver with a select group of passengers on board, and 43 hours later, including stops for firewood and one overnight stay, arrived at the young (founded 1883) town of Great Falls. The river flowing high with spring runoff from mountain snows enabled the Rose to descend Pine Island Rapid and return without major difficulties. The excursion party returned to Hilger’s landing six days after its departure, logging a round-trip running time of 40 hours and 37 minutes. During the next 19 years the Rose of Helena carried about 10,000 passengers through the Gates of the Mountains, and after a ten-year hiatus during which Holter Dam was built, Nicholas Hilger’s son David renewed the summer tours with a gasoline-powered cruiser.[4]Great Falls Tribune, 11 November 1923. Gates of the Mountain Boat Tours, Inc., is still in business, plying part of the 21-mile stretch of Holter Lake between the dam and Upper Holter Lake.

In the 1870s and 80s there was some mining for gold and sapphires, mostly above the canyon at Ming Bar, and at American Bar immediately above the entrance to the 5½-mile-long canyon.

Gates of the Mountians is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. Several sites managed by the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest are accessible by car or boat.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | Although the end of Lewis’s thirteenth and last Course for 19 July can be identified with a high degree of confidence, his final remark leaves much room for interpretation: “a little short of the extremity of this course we encamped on the Lard. side.” Sites A and B were chosen by combining an interpretation of Lewis and Clark’s usual meaning of “a little short of” with a detailed study of Missouri River Commission Plate L”, 1895 (scale of 1 inch = 1 mile) and the US Geological Survey’s Geologic Quadrangle Map GQ-840, Upper Holter Lake, 1969 (scale of 1 inch = 2000 feet). The end of Lewis’s Course 13 would be 46°49’54″N, 111°55’42″W. All coordinates stated here are based on 1927 horizontal datum; the 1983 datum used by Google Earth places the same coordinates about 12 meters farther north and 150 meters farther east. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Kenneth Bjork, “Norwegian Gold Seekers in the Rockies,” Norwegian-American Studies, Volume 17 (1952), p. 47 and following. http://www.naha.stolaf.edu/pubs/nas/volume17new/vol17_3.html. Accessed 3 February 2007. |

| ↑3 | Undaunted Stewardship, http://m.helenair.com/news/local/sieben-hilger-ranches-to-get-stewardship-interpretive-displays/article_905ae146-1491-5d9a-baa6-08b2a40f805e.html. Accessed June 2015. Undaunted Stewardship is a cooperative federal-state-private land management program dedicated to ensuring “the long-term maintenance of environmental quality and economic productivity of privately-owned agricultural landscapes, especially in areas rich in history along the Lewis & Clark Trail in Montana.” The Hilger Hereford Ranch, now combined with the historic sheep ranch of Henry Sieben, is owned by U.S. Senator and Mrs. Max Baucus. |

| ↑4 | Great Falls Tribune, 11 November 1923. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.