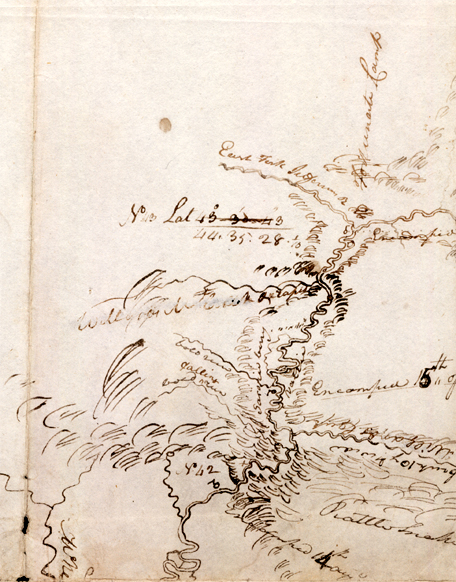

The Beaverhead River’s End[1]Moulton, Journals, vol. 2, Atlas, Map 66.

To see labels, point to the map.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Lewis Crosses the Rockies

It was a comfortable 60° Fahrenheit at sunrise on 10 August 1805, when Lewis, with George Drouillard and Privates John Shields and Hugh McNeal, set out from the previous night’s camp a few miles down “Jefferson’s [now Beaverhead River” below today’s Dillon, Montana.

“We continued our rout along the Indian road,” Lewis wrote, “which led us sometimes over the hills and again in the narrow bottoms of the river till at the distance of fifteen Ms. from the rattle snake Clifts [Rattlesnake Cliffs] we arrived in a ha[n]dsome open and leavel vally where the river divided itself nearly into two equal branches; here I halted and examined those streams and readily discovered from their size that it would be vain to attempt the navigation of either any further.” He sent Drouillard and Shields to explore the two roads separately and compare the frequency of their use. On the basis of their findings, he started up the southeast, or left-hand fork—the Red Rock River. When that turned out to be a dead end, he made his own reconnaissance, and headed up the west fork. That night the four men camped about a mile and a half west of the forks of the Jefferson.

On the eleventh, about ten miles west of the forks, in the flat valley Lewis named Shoshone Cove, they caught sight of a lone man on horseback, the first Indian they had seen since leaving Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805, 139 days before. Despite Lewis’s ardent efforts to establish contact, the Indian fled, perhaps to spread the alarm that invaders were approaching. Frustrated by the mischance, and with anxiety rising in his breast, Lewis led his party across the Continental Divide.[2]The geographical concept of a Continental Divide did not emerge until the 1840s. Lewis and Clark merely regarded the ridge as the dividing point between the Missouri and Columbia River drainages, and … Continue reading

The River’s End

A week later, on Friday morning, 16 August 1805, Captain Clark, with 26 men plus Sacagawea and seven-month-old Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, wakened at dawn just four miles downstream from what would be the western terminus of their Missouri River voyage. The air was so cold (48° Fahrenheit, according to the monthly record), and the men so “fatiged Stiff and Chilled,” that rather than begin the day as usual with a few hours on—that is, in—the river, Clark decided to “detain & take brackfast before I Set out . . . at 7 oclock.”

The labor of threading their way between the willow-fringed river banks brought the hardy enlisted men to the brink of their endurance. Yet no matter how daunting the moment-to-moment job of merely “proceeding on” from one landmark or one riverbend to the next, neither captain ever neglected his four primary jobs—command, the military work; exploration, the visual work; description, the intellectual work; and discovery, the comprehensive, “philosophical” work. Clark’s command was typically firm but kind. On the 12th the men “complain verry much of the emence labour they are obliged to undergo & wish much to leave the river. I passify them.” On the 13th they were “obliged to haul the boat[s] 3/4 of the Day over the Shole [shallow] water.” Meanwhile, keeping one eye peeled for rattlesnakes, he routinely absorbed more benign details of the natural world. His mind was busy, his pen swift.

I saw a great number of Service berries now ripe. the Yellow Current are also Common I observe the long leaf Clover in great plenty in the vallie below this vallie— Some fiew tres on the river no timber on the hills or mountn. except a fiew Small Pine & Cedar. The thmtr. Stood at 48° a[bove] o at Sunrise wind S W. The hunters joined me at 1 oClock, I dispatched 2 men to prosue an Indian roade over the hills for a fiew miles, at the narrows I assended a mountain [probably on the south side of Clark’s Canyon, the Beaverhead Canyon Gateway] from the top of which I culd See that the river forked near me the left hand appeared the largest & bore S.E. the right passed from the West thro’ an extensive Vallie, I could See but three Small trees in any Direction from the top of this mountain. passed an Isld. and encamped . . . on the Lard. [larboard, left] Side the only wood was Small willows

Clark’s Erroneous Observations

Clark’s celestial observations at Rattlesnake Cliffs on the fifteenth proved futile. At Point of Observation No. 42 (see map above), he recorded the “Meridian Altitude of [the sun]’s L[ower] L[imb] 0[3]A meridian is a line that passes through the north and south poles of a sphere of rotation, and is perpendicular to the equator of that sphere. A meridian altitude is the angle of the sun above the … Continue reading with Octant by the back observation.”

By his calculation the latitude of the Point was 44° 0′ 48.1″ north of the equator. This result was much in error, actually corresponding to a location 77 miles south of Rattlesnake Cliffs. In fact, at some point in time, Lewis added a note to Clark’s journal entry for the 15th that read, “this place ought to stand at about 44° 50′ or thereabouts.” The explanation may be traceable to the fact that although Clark recorded most of his observations as being of the sun’s lower limb (L.L.), he actually sighted on the upper limb. He may have been using the instrument with the telescopic eyepiece, which gave a clearer view, but reversed the image.

At first, on his map of the area (see above), Clark located the forks of the river and the site of Fortunate Camp, where he arrived on the seventeenth, at 43° 30′ 43″ North, which represents a considerable error. On the following page Professor Robert N. Bergantino, of the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, offers some explanations, and illuminates the intricacies of the procedures used in celestial navigation.

Notes

| ↑1 | Moulton, Journals, vol. 2, Atlas, Map 66. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The geographical concept of a Continental Divide did not emerge until the 1840s. Lewis and Clark merely regarded the ridge as the dividing point between the Missouri and Columbia River drainages, and as such, part of the boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Nevertheless, although they crossed Lemhi Pass five times during the month of August 1805, they never once made celestial observations to determine its latitude or longitude. |

| ↑3 | A meridian is a line that passes through the north and south poles of a sphere of rotation, and is perpendicular to the equator of that sphere. A meridian altitude is the angle of the sun above the equator when it passes through the midpoint between the eastern and western horizons. The sun’s (or moon’s) upper and lower limbs are the upper and lower tangents of their apparent disks as seen from Earth. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.