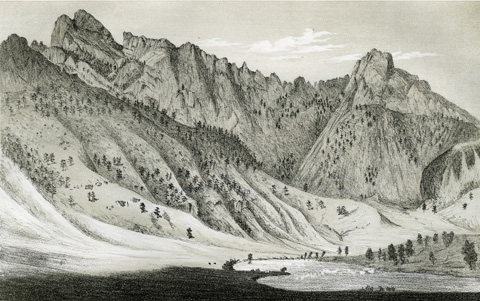

Stanley’s Chromolithograph

The Bear’s Tooth, 1855

John Mix Stanley (1814–1872)

Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

This chromolithograph was based on a drawing by John Mix Stanley, one of the artists who accompanied the Isaac Stevens expedition in the early 1850s.[1]Isaac I. Stevens, Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-Ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound, 12 … Continue reading The original caption read: “The Bear’s Teeth, a prominent landmark near where the Missouri issues from what Lewis and Clark denominate the Gate of the Mountains.” Stanley’s conception was more drama than truth, since the outcrops that looked like “bear’s teeth” were not the highest points on the mountain. (Compare this view with the last aerial photo below.)

Believing they were approaching the territory of the Shoshone Indians, and eager to make contact with them soon, on the afternoon of 18 July 1805, Clark left Lewis in command of the six canoes while he, with Joseph Field, John Potts, and York, forged ahead overland on the north side of the river. They “passed over a mountain on an Indian rode by which route I cut off Several miles of the Meanderings of the River, the roade which passes this mountain is wide and appears to have been dug in maney places [emphasis added].”

Those last eight words seem to suggest that Clark and his party were on the the ancient Indian road that has come to be known as the Old North Trail. Native peoples used it for thousands of years for their migrations and other travels southward from today’s Canada along the eastern margin of the Rocky Mountains as far south as New Mexico. The scuffing of many thousands of moccasins, and more recently horses’ hooves, plus the scraping of the tips of countless travois poles, combined to leave an imprint on the land that looked to William Clark like deliberate human engineering.

Apparently neither of the captains noticed this landmark, even though it was visible from the Missouri River five miles away both upstream and down, as well as from the Indian road Clark was following. Perhaps either they had never been told precisely what to look for, or else they simply didn’t have it in mind.

Mathews’ Lithograph

“Bear Tooth Mountain” c. 1865

Alfred Mathews

Mansfield Library, The University of Montana, Missoula

by Alfred E. Mathews (1831-18874). Plate 20, from Pencil Sketches of Montana.

Mathews—who himself published his collection of lithographs in 1868—wrote of this scene: “Just below the Gate of the Mountains, on the west side there is a secluded valley of a few hundred acres, shut in by lofty mountains. Bear Tooth Mountain can be seen to the best advantage from this valley. The summit of the mountain, as seen from the Helena and Fort Benton road, has some resemblance to the teeth of a bear; hence its name.”

Geological understanding of the Rocky Mountains advanced slowly but steadily during the second half of the 19th century. Mathews wrote in his caption that The Tooth was “of porphyry rock in many places covered with carbonate of lime that appears like a slight sprinkling of snow.” Either he had enough knowledge to make his own judgment on the subject, or he had gotten some tips from a miner in Helena. We now know, according to Robert Bergantino, that the part of Beartooth Mountain from which it got its name is composed mostly of Late Cretaceous rhyodacite, an igneous gray-brown aphanitic rock containing phenocrysts of Labradorite, which give the formation its porphyritic texture. Labradorite is a lime-soda feldspar, and the weathering of the larger crystals could produce a coloration that resembles what Mathews referred to as “carbonate of lime.” Or was he only looking for some feature that could be said to support the likening of those jagged spires to real teeth?

The road Mathews referred to connected Helena (founded in 1864; locally pronounced hel-leh-nuh), the newest and most prosperous mining town in Montana Territory, with Fort Benton (established 1850), the upper terminus of commercial steamboat traffic on the Missouri River. The narrow 66-mile unpaved stagecoach route followed portions of the ancient Indian trail that Clark had traveled. It took him within two miles—and plain sight—of the Bears Tooth.

Wheeler’s Photo

View from the Summit of Bear’s-tooth Mountain,

just below the Gates of the Rocky Mountains,

Showing the Missouri River, 1902

Olin D. Wheeler, The Trail of Lewis and Clark. See also Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

Olin Wheeler, author of the first traveler’s guide to the Lewis and Clark trail, climbed Beartooth Mountain in about 1902 with his photographer, possibly Ralph DeCamp of Helena, Montana, and captured this historic view eastward. Across the river is the Beartooth State Game Management Area; the intermittent dark line marks the Cottonwood Creek drainage.

Inasmuch as no member of the Lewis and Clark expedition climbed Beartooth Mountain to get such a view, the photo merely suggests how different their general understanding of the western mountains might have been if they had. Coincidentally, during that first decade of the 20th century, while Wheeler was retracing the trail of Lewis and Clark, the Wright brothers were developing their first experimental fixed-wing aircraft with which a bird’s-eye view of Earth’s surface could be replicated by humans.

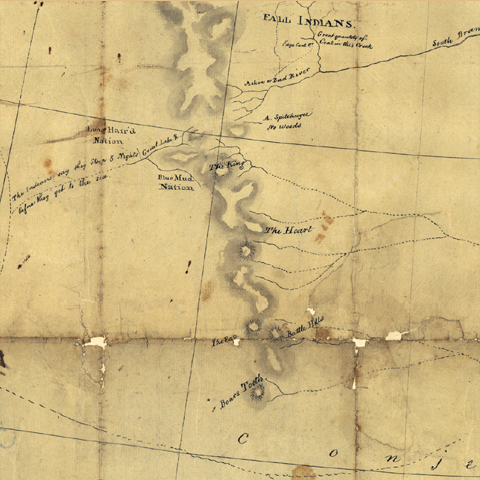

Interactive Maps

Rocky Mountains (Conjectural, 1803-1804)

Detail from the map of the Northwest

drawn by Nicholas King in 1803,

at the request of Albert Gallatin, for Lewis and Clark.

To see labels, point to the map.

Library of Congress

King’s depiction of the Rocky Mountains was based on a map created by the British cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith in 1795. When preparations were being made for the expedition of Lewis and Clark it was considered the most accurate chart of the western region of Louisiana territory.[2]John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), 102, 123, 176. Note that the Rockies were believed to terminate near the 45th Parallel. Not until … Continue reading The landmarks shown in King’s collation had been described and mapped in 1801 by a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company, Peter Fidler, with the assistance of the Siksika Indian chief, Ac ko mok ki, sometimes known to fur traders as “Old Swan.” Ac ko mok ki knew the Bears Tooth as ‘Ki oope kis.

Lewis recognized “The Pap”—which he had been told was called “Shisequaw Mountain” [Haystack Butte]—on his return shortcut from Travelers’ Rest back to the Great Falls of the Missouri, and he also had foreknowledge of the Bears Tooth. Back at the mouth of the Marias River on 8 June 1805, as he sought to understand the geographical implications of this unanticipated tributary, and imagine the location of the Missouri’s source, he pored over Nicholas King’s map again. “I see,” he wrote, “that Arrasmith . . . has laid down a remarkable mountain in the chain of the Rocky mountains called the tooth nearly as far South as Latitude 45°.”[3]King, following Arrowsmith, showed the Bears Tooth, with the supposed middle fork of the Missouri River rising from its flanks, at approximately 46° north latitude. The location was remarkably … Continue reading Either that detail slipped his mind in the intervening 41 days, or he was distracted by more pressing matters during the short time when he could have seen the Tooth from the river.

Aerial Views

Holter Lake (Missouri River)

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2001 Airphoto, Jim Wark. All rights reserved.

Bear Tooth Game Range

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2001 Airphoto, Jim Wark. All rights reserved.

Expanded and disguised as Holter Lake since since 1918 when Holter Dam was completed a dozen miles or so downstream from here, the Missouri River still shoulders its way around Ming Bar and Ox Bow Bend. The former was named for a successful late-19th-century rancher, John H. Ming, of Helena, who grazed some of his cattle on the east side of the Missouri River. Beyond the bend the outcrop representing the largest “tooth” is visible to the right of center, towering approximately 2,500 feet above the surface of Holter Lake.

Early on a May morning, Jim Wark’s plane soars over the Bear Tooth Game Range opposite sprawling Beartooth Mountain, its featured landmark nearly lost in the dim light, from this distance. Faintly visible on the distant horizon, more than 100 miles westward, are the heights of the Bitterroot Mountains that the expedition would eventually have to cross, though the men wouldn’t see them for the first time until another month had passed since their day-trip around Ox Bow Bend.

An oxbow was a U-shaped wooden collar that fitted under the neck and against the shoulders of an ox, enabling it to pull a cart or wagon. The narrow point of land embraced by the river’s bend was once called “Mandible Point” because it is shaped like the lower jaw of an animal such as an ox or a cow.

Today’s Landmark

No longer a useful landmark or trail marker, the Bears Tooth nevertheless captures modern travelers’ attention as they pass by on Interstate Highway 15 a short distance north of Helena. Probably few if any viewers realize what they’re really looking at.

Notes

| ↑1 | Isaac I. Stevens, Narrative and Final Report of Explorations for a Route for a Pacific Railroad near the Forty-Seventh and Forty-Ninth Parallels of North Latitude, from St. Paul to Puget Sound, 12 Vols. (Washington, D.C., 1855), Vol. 12, Book 1, facing p. 176. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (New York: Dover, 1975), 102, 123, 176. Note that the Rockies were believed to terminate near the 45th Parallel. Not until late in the 19th century was it understood that they extend from the Laird River in northern British Columbia all the way to the Rio Grande River in New Mexico. |

| ↑3 | King, following Arrowsmith, showed the Bears Tooth, with the supposed middle fork of the Missouri River rising from its flanks, at approximately 46° north latitude. The location was remarkably close, considering that Arrowsmith’s informant, Peter Fidler, had not been that far south himself. It was a good guess; actually the landmark stands at 46°54′, or roughly 70 miles north of where King placed it. Incidentally, in King’s map the appearance of “Boars” for “Bears” probably was the engraver’s misprint. Ac ko mok ki called the Bears Tooth—in Fidler’s transliteration—‘Ki oape kis. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.