The familiar route the Indians were accustomed to would have led them back across the Continental Divide into an upper Missouri River drainage and then back to Western waters. But the captains had already come many days and miles out of their way to reach the Shoshones, the end of the travel season was nearing, and the Pacific Ocean was still far away. It seems that the captains simply refused to take a single step that would not carry them forward toward their objective.

All we know for certain about their route on 2 September 1805–4 September 1805 is that it was extremely difficult and hazardous. Early on the 2nd they had to fight their way through dense underbrush and over rocky terrain. Their horses were continually in danger of “Slipping to Ther certain distruction . . . Several horses fell, Some turned over, and others Sliped down Steep hill sides.” None of the horses were shod, so the risk of lameness was always present, and indeed, as Clark wrote, the party suffered “one horse Crippeled . . . 2 gave out.” Gass added “a good deal of rain” drenched them that afternoon. Then the canyon became so narrow that they were “obiged to go up the sides of the hills . . . and then down again in order to get along at all.” In short, it was “the worst road (if road it can be called) that was ever travelled.” One of their horses was “so badly hurt that the driver was obliged to leave his load on the side of one of the hills.”

Misery Mounts

The next day was worse. The weather turned against them, and visibility must have been close to zero at times. At least one student of the episode believes that they might unknowingly have walked along the nearby Continental Divide and through the saddle now known as Lost Trail Pass. By evening, Clark recalled, “Snow [was] about 2 inches deep when it began to rain which termonated in a Sleet.” The going was still rough and steep, and now slippery too. No mention is made of it, but the wet snow probably balled up on the horses’ hooves and caused them to stumble every so often.[1]On 10 May 1806, when the Corps was recrossing the Bitterroot Mountains, Clark mentioned that problem: “the road was Slipry and the Snow Cloged and caused the horses to trip very … Continue reading Water dribbled from every branch of every tree, sluiced from every bush and blade of grass. Their sopping-wet leather clothing sponged life-warmth out of their bodies daylong and nightlong. They could only have survived by force of will and sense of mission. And they did.

Lost?

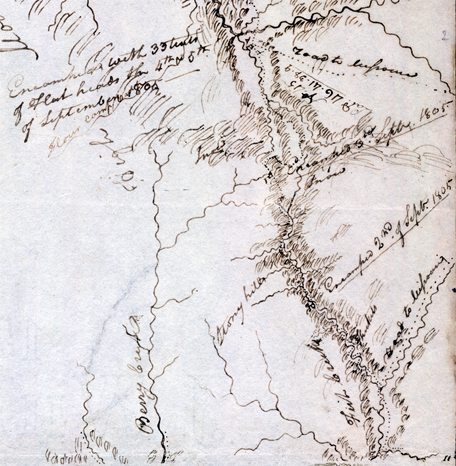

Clark’s journal for 3 September 1805 informs us that at the end of that day they “encamped on a Bran[c]h of the Creek [they] assended after crossing several steep points and one mountain.” We can’t say for sure that they were lost, and they didn’t admit to it in so many words, but Sergeant Gass’s laconic remark gives us a hint: “This was not the creek our guide wished to have come upon.”[2]Gass’s quote of Toby‘s apology may be the very thing that has driven serious students and scholars of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to devote so much attention to the whereabouts of the … Continue reading Fortunately, the topography provided Toby the perspective he needed in order to determine the next day’s route.[3]See also on this site Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”.

But really, where did they camp? This was not the only time Toby was unsure of himself, nor that the captains were temporarily baffled, but it is perhaps the one that most readily invites study and discussion. In July 1997, the Salmon and Challis National Forests, and several other agencies and associations, sponsored a symposium of five amateur and professional historians and cartographers, each of whom described and illustrated his own theory as to the route the Corps might have followed, and the location of their camp on that night. The event was highlighted by an on-site exploration of each of the possibilities. In this instance, hindsight served merely to illuminate the scope of their uncertainty, but it dramatically underscored the adventure that the men faced almost daily on their journey through the wilderness.

Cold Night

Saddle Mountain Viewpoint

© 8 September 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Above: Had the weather been clear, the travelers would have found their way over the divide much sooner.

The Corps had other matters on their minds. One was hunger. Clark’s journal continued: “but little to eate I killed 5 Pheasents [grouse] & The huntes 4 with a little Corn afforded us a kind of Supper.” Another was physical danger. They struggled over “emence hils and Some of the worst roade that ever horses passed.” Frequently the horses fell, and in one such instance, lamented Clark, “we met with a great misfortune, in having our last Thmometer broken by accident.” Worst of all was the weather. At dusk that day it began to snow, and misery continued to pile upon misery—”Snow about 2 inches deep when it began to rain which termonated in a Sleet.”

After a night of what could only have been a shivering, fitful rest from bushwhacking, they wakened on the 4th with their moccasins frozen. Their fingers aching with the cold, they packed their horses, quickly breakfasted on a little parched corn, and “ascended the mountain on to the dividing ridge and followed it Some time.” Descending steeply between the two forks of Camp Creek into the East Fork valley of the Bitterroot River (their “Clark’s River”) that afternoon they came upon a large band of Salish people—”Tushepau,” or “Flat head” Indians, as the captains learned to call them. The Indians were camped in the little mountain valley, or “hole,” which bears the name of the well-known Canadian who camped there for a month with his company of free trappers only nineteen years later, Alexander Ross.

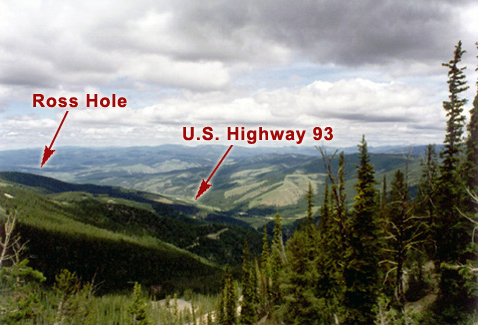

It was 19° above zero at sunrise on the fourth, but the sky had cleared. From this, the high point on Bitterroot Divide, the Corps’ view down the headwaters of the Bitterroot River toward the northeast looked very much like this, except that the higher elevations were white with a few inches of new snow—”over our mockasons in places,” according to Ordway. If the Corps could see smoke from the Salish camp down in the valley, none of the journalists mentioned it.

Bushwhacking through ‘the place’

On a balmy Indian-summer day in September 1997, some 20 men and women followed five experts on “the September 3rd campsite” puzzle up and down the west-facing slopes southeast of Saddle Mountain. Each of those five held his own carefully developed theory of where the Corps walked that day, and where they camped. Two or more agreed on some points, but no two agreed on all. Yet their differences were not far apart, either logically or geographically. All of the possible campsites lay within about one sloping square mile of sub-alpine forest.[4]James R. Fazio, ed., with Robert N. Bergantino, J. Wilmer Rigty, Hadley B. Roberts, Steve F. Russell, and James R. Wolf, “The Mystery of Lost Trail Pass: A Quest for Lewis and Clark’s … Continue reading

Three of the leaders are pictured here, warm and dry, bushwhacking through the forest where one or more of the five believed those wet, cold and exhausted young men—as well as young Sacagawea and her six-month-old baby boy!—huddled that stormy night in the snow and sleet. If this really was “the place,” then doubtless the largest of those fallen dead trees were standing tall and strong above them that night.

More than likely, the precise location of the Corps’ camp on 3 September 1805, will never be known. The journalists’ records, which more than likely were recollections written some time later, are brief, ambiguous, and sometimes contradictory. They clearly indicate that the men were not following a well-used Indian road, nor even a way that Indian travelers would have chosen under any circumstances. The dense forest, the steep, narrow draws they climbed up and down, and the stormy weather that cloaked the mountains those two days prevented them from referencing distant landmarks that we might now use to reconstruct their journey during those few miserable hours.

Climbing the Divide

Saddle Mountain and the Lost Trail

To see labels, point to the image.

© 2002 Airphoto, Jim Wark. All rights reserved.

This photograph, looking west-southwest (250° from true north), was taken in May 2002. The blackened areas were burned in August 2000, but dense green ground cover has already begun to grow again among the blackened and scorched trees. The burned area shown here was but a small portion of the Valley Complex Fire, which was a joining-together of a number of separate lightening-caused blazes into the largest single forest fire in the Northwest that season. It started on 31 July 2000, and was finally extinguished by high-country rain and snow on the 3rd of October, having burned a total of 292,070 acres, or 456 square miles. Three other major fires in central Idaho that year burned a total of 925 square miles of forest and grassland, for a total of 1381 square miles blackened.

Clark’s exploration of the Salmon River ended about thirty air-miles from this mountain, at about the center of the picture and somewhat this side of the highest peaks. The road winding through the left foreground of the picture is a forest access road that originally was built for hauling logs to market, and now is used for recreational purposes as well as for resource management, such as the salvage of burned timber and the replanting of trees.

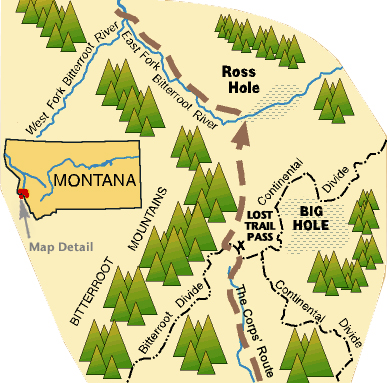

Lost Trail Pass, which the Corps probably did not see, is out of the photo at lower left, two miles east-southeast of the highest point of the ridge. U.S. Highway 93 crosses the Bitterroot Divide there at an elevation of 7014 feet above sea level. It was not named to memorialize Toby’s error, but because the surveyors who laid out the highway route around 1910 were said to have gotten temporarily confused as to where they were one day. Another mile east of Lost Trail Pass, Montana Highway 43, which intersects with U.S. 93 on the pass, crosses the Continental Divide via Chief Joseph Pass at 7264 feet.

Since arriving at the headwaters of the Missouri River, and reaching the Continental Divide at today’s Lemhi Pass on 12 August 1805, the men of the expedition had met Sacagawea’s people, the Shoshone Indians, confirmed the Indians’ experience that the Salmon River canyon was impassable, and purchased 29 undernourished, sore-backed, ill-mannered horses to carry their baggage across the Bitterroot Mountains to the navigable reaches of the Columbia River basin.

On the 30th they bade farewell to Sacagawea’s people, who were headed for the Three Forks of the Missouri where they would join their Salish friends and proceed to their annual bison hunt on the high plains. Forthwith, accompanied by a Shoshone guide—Toby and his sons—the Corps set out northward from Lemhi River country and headed for the Indian road that they had been told would lead them across the Bitterroot Mountains.

Seeking the shortest way over the Bitterroot Divide, they labored up the head of the North Fork of the Salmon River, instead of following the more circuitous Indian road that wound back over the Continental Divide to the east. Wild game was scarce, so they were on short rations.

The slopes were heavily timbered, and in many places the underbrush was so dense they had to hack their way through it with their hatchets. Elsewhere the mountainside was so rocky and steep that the horses frequently fell. An early-season snowstorm, followed by rain and sleet, made things worse. No one knows for certain which way they went on September third. There are no obvious natural routes; the journal description is vague, and details may be erroneous.

Descending to Ross Hole

On the morning of the fourth, their fingers aching from the cold and their moccasins frozen on their feet—the thermometer read 19° Fahrenheit at dawn—they began their trek down the north slope of the Bitterroot Divide, staying just above the brushy bottoms of the rushing stream now known as Camp Creek, which still “waters” the narrow canyon. The ankle-deep snow at first, followed without interruption by cold rain, combined with the steepness of the stream’s course, made their descent extremely hazardous and painfully slow. Most of the men were leading their loaded pack horses, an exercise that often required skillful footwork for their own safety, and unrelenting attention to dangers that lay just ahead. Every step placed them on the brink of injurious if not fatal accident. Their goal was to intersect with the Indian road that would carry them down the valley of today’s Bitterroot River, but which they dubbed “Clark’s River.” If they had spied that drainage from the highest point on the ridge that bounded it, their destination for the day was about ten miles and 3,400 vertical feet away—an an exhausting descent of 340 feet per mile.

Toward evening they arrived at a small, flat, grassy valley ringed by mountains—a rond or “hole,” as trappers would call it—and encountered there a large encampment of Salish Indians. Sergeant Ordway noted in his journal that there were about 400 people, 40 lodges, and four or five hundred horses.

Clark’s Impressions

Clark summarized his impression of the people:

those people recved us friendly, threw white robes over our Sholders & Smoked in the pipes of peace, we Encamped with them & found them friendly but nothing but berries to eate a part of which they gave us, those Indians are well dressed with Skin ShirtS & robes, they Stout & light complected more So than Common for Indians, The Chiefs harangued untill late at night, Smoked our pipe and appeared Satisfied. I was the first white man whoever wer on the waters of this river.

Immediately the Americans took a genuine liking to the Salish, who responded in kind. “They are the likelyest and honestest we have seen and are verry friendly to us,” wrote Sergeant Ordway, “and appeared to wish to help us as much as lay in their power.”

Ross Hole Today

You can see this rond as the Corps of Discovery saw it, if you can imagine this scene without barbed wire fences, electric power poles, farmstead outbuildings, gate posts embellished with no-trespassing signs, and asphalt pavement that is only a short distance to the right of the photo from the place where the Corps most likely camped that night.

Construction of U.S. Highway 93 began, piecemeal, in the mid-1920s. It now extends from the Canadian border above Eureka, Montana, to the town of Wickenburg in southern Arizona, where it ends at its junction with U.S. Highway 60. In southwestern Montana it follows the Indian “road” that the Corps of Discovery traveled northward from the headwaters. In fact, parts of it lie atop sections of the ancient trail the Corps traveled all the way from the town of Salmon, Idaho, to Ross Hole. The Corps probably camped a short distance from the right edge of this photo on the night of 5 September 1805, and spent the next day with the Salish, who were en route by another road to Three Forks to join forces with a Shoshone band to hunt bison—no doubt the same band of Shoshone hunters they had parted from on 30 August 1805.

Only about three miles in diameter, Ross Hole is much smaller than the sprawling Big Hole, which lies to the south, on the east side of the Continental Divide, and was transected by the “excellent road” which Clark and his contingent followed on 6–8 July 1806, on their return trip to reclaim their dugout canoes at Fortunate Camp. For countless generations Ross Hole served as a comfortable resting and meeting place for Salish, Shoshone, and Nez Perce travelers.[5]For photos comparing the forest surrounding Ross Hole in 1895, with the same location in 1980, see “Unviolated Forests, “Now and Then.”

Gibbons Pass is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The route can be traveled in the Bitterroot National Forest on Forest Road 106.

Ross Hole is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. On US Highway 93, at the Sula Country Store, a road-side pull-off provides views of the valley and interpretive signs.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | On 10 May 1806, when the Corps was recrossing the Bitterroot Mountains, Clark mentioned that problem: “the road was Slipry and the Snow Cloged and caused the horses to trip very frequently.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gass’s quote of Toby‘s apology may be the very thing that has driven serious students and scholars of the Lewis and Clark Expedition to devote so much attention to the whereabouts of the Corps of Discovery on 3–4 September 1805. Elliott Coues (1893) enhanced Nicholas Biddle‘s (1814) straightforward narrative of the Corps’ experience by summarizing the journal entries and devoting a long word-picture to the distinction between the Bitterroot Divide and the Continental Divide. Olin D. Wheeler (1904) focused more on the journalists’ ambiguities regarding the descent into the Bitterroot River drainage, and the location of the Salish camp. Reuben Thwaites(1904) ignored the question of the campsite, simplified the route on the two days in two short sentences, and quoted Wheeler on the rest. |

| ↑3 | See also on this site Wheeler’s “Trail of Lewis and Clark”. |

| ↑4 | James R. Fazio, ed., with Robert N. Bergantino, J. Wilmer Rigty, Hadley B. Roberts, Steve F. Russell, and James R. Wolf, “The Mystery of Lost Trail Pass: A Quest for Lewis and Clark’s Campsite of September 3, 1805,” WPO [We Proceeded On] Publication No. 14 (February 2000), Great Falls, Montana: Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc. Local interest kept the matter on the fringes of historical awareness for several decades until 1958, when an Idaho State University professor, John E. Rees, published “The Shoshoni Contribution to Lewis and Clark,” in Idaho Yesterdays, Vol. 2 (Summer 1958): 2–13. Serious interest gained more momentum six years later with the work of the Boise, Idaho, engineer, John J. Peebles, who published “Rugged Waters: Trails and Campsites of Lewis and Clark in the Salmon River Country,” Idaho Yesterdays 8 (Summer 1964): 2–17. Upon those systematic foundations a substantial body of serious studies has been built, which continues to spawn its own extensions. Actually, the locale of the 3–4 September routes and camp is much easier to determine than many other Lewis and Clark ways and stopping paces. Perhaps the probability that the terrain still appears much as it did in 1805 is what makes this otherwise irrelevant little puzzle so enticing. Also, the fact that it’s all public land makes it easy to study. |

| ↑5 | For photos comparing the forest surrounding Ross Hole in 1895, with the same location in 1980, see “Unviolated Forests, “Now and Then.” |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.