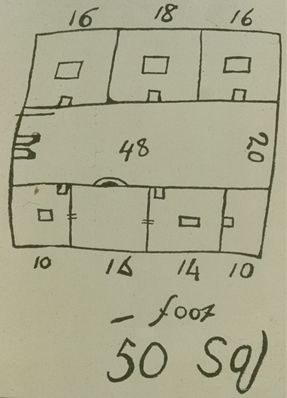

Above is a copy of the floor plan for Fort Clatsop that was drawn on the outside back cover of Clark’s field journal, which he had covered with elk skin to keep its contents clean and dry. He drew another, slightly different layout elsewhere, but evidence clearly shows that this is the one that was used.

Day 1—10 December 1805 marked the beginning of work on the Corps’ third winter garrison. That was the day Clark returned from supervising the placement of the salt-makers’ camp on the beach, to find all hands–those who weren’t too sick to work–clearing the ground and staking out the plan of the structure. They worked as fast as they could, and the daily, mostly intermittent rain showers punctuated by gale-lashed torrents, strengthened their resolve.

Day 2—11 December 1805. They raised the log walls of one line of huts. There was no need to take time to peel the logs. In fact, the mud daubing they were to apply to keep out the wind would adhere better to rough bark than to bare wood.

Day 3—12 December 1805 brought satisfying progress, and their first major challenge: “In the forenoon we finished 3 rooms of our cabins,” Sgt. Gass reported, “all but the covering; which I expect will be a difficult part of the business, as we have not yet found any timber which splits well; two men went out to make some boards, if possible, for our roofs.”

Day 4—13 December 1805. Everyone’s spirits got a boost. Their two unnamed loggers found exactly what was needed—western redcedar (Thuja plicata Donn ex D. Don). Now they could rive (split) boards from those tree trunks to roof their huts in order to keep out wind and rain, and the wood would exude its clean, stimulating balsamic aroma to comfort the occupants and allay some of the stress of living in close quarters during the endless days of semi-confinement.

Puncheon

Fort Clatsop, Replica

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Day 5—14 December 1805 was a benchmark day. “We completed the building of our huts, 7 in number,” Sgt. Gass reported hopefully, “all but the covering, which I now find will not be so difficult as I expected; as we have found a kind of timber in plenty, which splits freely, and makes the finest puncheons [planks] I have ever seen. They can be split 10 feet long and two broad, not more than an inch and an half thick.” It is not clear whether the sergeant’s remark should be read as evidence that the Corps did indeed have a froe (Fig. 3) with them, and that its head was a little over two feet long.

That day also brought a discovery that boded ill for them, although it took them another week or more to come to the full realization of it. “[A]ll our last Supply of Elk,” Clark lamented, “has Spoiled in the repeeted rains which has been fallen ever Since our arrival at this place, and for a long time before.” Throughout November and December there were several days when the sun shone through for a few hours, but seldom long enough to draw much moisture from anything beneath it.

Day 6—15 December 1805 was spent by Gass and two others in “fixing and finishing the quarters of the Commanding Officers,” while two other men were “preparing puncheons for covering the huts.”

Puncheon or punchin? Puncheon has been a wiggly word all its long life. From the mid-14th century on, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, it denoted a tool for 1) punching holes, 2) making dies for coins, or 3) casting printers’ type. Three hundred years passed, and somehow it turned into the name for a small split log laid with the flat side up as paving material for a road or walkway. For Patrick Gass it was either a split log or a thin plank split from a larger log. But Noah Webster, in his first dictionary (New Haven, Connecticut, 1806), retained the old definition, simplified: “a tool to make a hole” and also, incongruously, as “a large cask.” Meanwhile, “a short timber for supporting weights” was termed a “punchin.” One suspects that Webster’s own pet peeves—regional, local or even household speech and spelling habits, and provincial neologisms—were responsible for the lexical mess.

Meathouse

Fort Clatsop (replica)

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 1995 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Day 7—16 December 1805. Clark: “[W]e had a house Covered with Punchen & our meat hung up.”

That was the best that could be said about December 16. Conditions were almost beyond tolerance. They had been without any night-time shelter to speak of since last July 7, at least, when they were still at the upper portage camp above the Great Falls of the Missouri. That was the day Lewis had reported: “[W]e have no tents; the men are therefore obliged to have recourse to the sails for shelter from the weather and we have not more skins than are sufficient to cover our baggage when stoed away in bulk on land.” And what were those pieces of canvas like after six more months of wear and tear? Did they shed any of the precipitation that fell day and night? The situation was no less depressing with regard to clothing. “[T]heir leather cloathes soon become rotton as they are much exposed to the water and frequently wet.” As we read of all the surprising and often exciting discoveries the journalists recorded in the Corps’ general behalf, it is easy to overlook those dismal deprivations. Who among us could have endured them with optimism and good cheer?

They were still sleeping under tattered pieces of sail, and it would be another week before all the rest of the huts could be roofed. Somehow, Clark managed to shelter himself from the rain long enough to document last night’s deluge: “I as also the party with me experienced a most dreadfull night rain and wet without any Couvering, indeed we Set up the greater part of the Night, when we lay down the water Soon Came under us and obliged us to rise.” So, he wrote, “we Covered our Selves as well as we Could with Elk Skins, & Set up the greater part of the night, all wet I lay in the water verry Cold.” The next morning, the storm took a turn for the worse. While the wind lashed them with torrential rain, Clark and a few of the men doggedly endured both adversities and slogged through the dense, thoroughly drenched undergrowth to retrieve the meat of several elk that had been shot the day before. Worst of all, mortal danger was literally in the air: “Trees falling in every derection, whorl winds, with gusts of rain Hail & Thunder.” The captain was almost at a loss for words. September 16 was “Certainly one of the worst days that ever was!” Still, he wrapped up his memories of the day with a ho-hum postscript: “Several men Complaining of hurting themselves Carry meet, &c.”

Netul Landing

Lewis and Clark River

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 2008 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

This is a typical wet and miserable winter day on the Pacific Northwest coast. Fort Clatsop was located on the hill in the far background. See also Lewis and Clark River.

Day 8—17 December 1805. It must have been frustrating to have to chop down a tall tree, the identity of which couldn’t be confirmed until the crown foliage was on the ground. After the men employed their froes, Clark noted that “the trees which our men have fallen latterly Split verry badly into boards.” So much for that plan. Moreover, sleeping conditions kept worsening: “our Leather Lodge has become So rotten that the Smallest thing tares it into holes and it is now Scrcely Sufficent to keep . . . the rain off a Spot Sufficiently large for our bead [i.e., bed, which Clark may have pronounced as a two-syllable word, bay-ed].” Think of young Sacagawea, and of ten-month-old Jean Baptiste Charbonneau.

Day 9—18 December 1805. Weatherwise, this morning wasn’t any better. In fact, it was much worse. It snowed, but they had to keep at it, and they were nearing the end of their endurance. “The men being thinly Dressed,” Clark sympathized, “and mockersons without Socks is the reason that but little can be done at the Houses to day.” At noon, however, “the Hail & Snow Seased and rain Suckceeded for the latter part of the day.” Thanks for small blessings.

Clatsop Plankhouse

Fort Stevens State Park

© 2010 by Kristopher Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Day 10—19 December 1805. Early this morning—under clear skies, for a change—Clark “despatched Sjt. Pryer with 8 men in 2 Canoes across Meriwethers Bay for the boads[1]In parts of 18th-century Britain, and among American Colonists and later immigrants who came from certain places in the British Isles, speakers typically elided the rhotic sound when it occurred … Continue reading of an Indian house which is vacant.”

Day 11—20 December 1805 found Sgt. Gass reporting, “We collected all the puncheons or slabs we had made, and some which we got from some Indian huts up the bay, but found we had not enough to cover all our huts.” The sergeant neglected to mention that they needed puncheons and planks not only for roofing but also for floors and bunks in all the rooms,[2]Peter C. Welsh, “Woodworking Tools, 1600-1900,” in Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, Paper 51. Project Gutenberg EBook #27238; release … Continue reading perhaps except the smokehouse, and for walkways in the parade enclosure to cut down on the mud that would unavoidably be tracked indoors.

Day 12—21 December 1805 saw steady progress in daubing the chinks between logs in the four huts that were roofed, and finishing their puncheon flooring and bunks. On the personal side, Clark “dispatched two men to the open lands near the Ocian for Sackacome [bearberry], which we make use of to mix with our tobacco to Smoke which has an agreeable flavour.” Frustrations were inevitable. On the twelfth day a couple of the men felled “Several trees which would not Split into punchins.” The crowns of most of the best trees were so far up the boles that confirming identification from foliage was impossible before they were on the ground.

Day 13—22 December 1805. This day brought another unwelcome lesson: “We discover that part of our last Supply of meat is Spoiling from the womph [warmth] of the weather not withstanding a constant Smoke kept under it day and night.” Evidently the wisdom of the day suggested that smoke would counteract any tendency toward spoilage.

Walls

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 2008 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

With all photos of the National Park Service replica, keep in mind that it was built to last several years, endure thousands of visitors, and prevent accidental burning. The original fort only needed to last a few months. Here, the logs have been rounded, smoothed, and finished.

—Kristopher K. Townsend, ed.

Day 14—23 December 1805 The captains moved into their hut today, even though it was not quite finished. Ordway hinted that boredom was setting in. “[N]othing extraordinary hapened more than common this day.”

Day 15—24 December 1805. It was Christmas Eve, and the first night in many weeks that all the men could share shelter from the wind and rain, and build fires in an effort to dry out their soggy leather clothes and bedding. Two weeks later, however, (on January 6) Lewis would declare his frustration over that persistent issue: “[W]e have not been able to keep anything dry for many days together since we arrived in this neighbourhood, the humidity of the air has been so excessively great.” His commander in chief would have been delighted with that tidbit of climatological information (the only occurrence of the word “humidity” in the journals), but Nicholas Biddle omitted it from his abridgement of the captains’ diaries and reports.

Day 16—Christmas Day, 25 December 1805. “All our party moved into their huts,” Lewis wrote. Clark was obviously pleased for them. “All the party Snugly fixed in their huts,” he wrote with satisfaction. But there was still more truth to be discovered about life on the northwest Pacific Coast, and much work to be done.

Day 17—26 December 1805. Today Joseph Fields [Joseph Field] “finish[ed] a Table & 2 Seats” for the captains. One can only speculate if any jacks or planes made it to Fort Clatsop. Life at the fort was somewhat more comfortable today, except for one daily complaint that had remained unspoken until now. Clark: “The flees are So troublesome that I have Slept but little for 2 nights past and we have regularly to kill them out of our blankets everyday for Several past.”

Chimney

Fort Clatsop, Replica

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 2009 by Kristopher K. Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The wooden chimney on the front of the Captains’ quarters predominates in this photo. Just beheind and to the left of that chimney is the style of chimney used for the other rooms in the modern reconstruction of Fort Clatsop. We do not know the placement or styles of chimneys used in the actual fort.

—Kristopher Townsend, ed.

Day 18—27 December 1805. In today’s journal entry, Captain Clark tried to sound nonchalant—”the men Complete Chimneys & Bunks to day”—whereas Ordway was somewhat more specific: “[W]e built backs and enside chimneys in our huts which made them much more comfortable than before.” It may be that they built stone hearths and chimneys, but since there is no indication that they had any cement or lime with them to make mortar, and given that they were to dwell in their bastion only three more months, it seems more likely that they arranged some stones carefully against the outer log wall, and a few more on the floor, chinked them all with mud, and erected some plank or elk-hide baffles to funnel smoke straight to the holes in the roof.

The design of those bunks is another matter worthy of speculation. Back in Philadelphia, as he gathered supplies for the expedition, Lewis purchased “1½ dozen Bed Laces.”[3]Jackson, Letters, 1:83. More expensive laces made of tape instead of rope were sometimes used as seats in stagecoaches to relieve passengers from painful jostling on rough roads. An everyday sign of sleeping comfort in those days, bed laces were nets made of hemp or sisal rope which could be fastened to holes or pegs in bed frames and “tuned” or stretched taut with a “bed key” to one’s personal measure of comfort. They were never referred to in the journals, so either they were too commonplace to be worth mentioning, or Lewis left them behind to cut costs. But if indeed they did carry them along, circumstances may have required that they be cut apart to provide strong ropes to tie up the manties of baggage and lash them to their pack saddles. And if not, at Fort Clatsop it seems likely they were all obliged to sleep on unyielding puncheons.

On December 27 Clark signed off on his field note, perhaps with a shudder of recognition, “Musquetors troublesom.” However, in the fair copy of this day’s journal he managed to suppress his anxiety. “Musquetors to day, or an insect So much the Size Shape and appearance of a Musquetor that we Could observe no kind of difference.” Likely, this insect was a crane fly.

Unquestionably, the best part of this day was centered on the visit of the Clatsops‘ Chief Coboway and four other men who, Clark recalled, “presented us” with a quantity of roots and berries which were “timely and extreamly greatfull to our Stomachs, as we have nothing to eate but Spoiled Elk meat.” We are left to wonder how inclusive that objective plural pronoun “us” was. The whole company of 33 hungry mouths? Or just the captains’?

Sentinel Box

Taken with permission of the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks, Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail. Photo © 2008 by Kristopher Townsend. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Day 19—28 December 1805. Clark “Sent out the hunters and Salt makers.” The rest of the sentence tips us off to an important detail on concept and construction: “& employed the balance of the men Carrying pickets &C.” In this case, the word ‘pickets’ was a military term denoting pointed logs driven or dug into the ground with the pointed end up, to make a stockade that would prevent or discourage unauthorized persons from climbing over it.

Day 20—29 December 1805. Chief Coboway and his companions departed from the vicinity of the Fort this morning. Clark sent him off with the gift of an old and evidently useless razor, which suggests that the men of the Corps were amply bearded by this time.

Today the Corps evidently got their first look at the waterproof coastal woven hats, made of cedar bark and beargrass leaves. Also, Clark was able to definitively summarize the local flea situation:

The flees are So noumerous in this Countrey and difficult to get Cleare of that the Indians have difft. houses & villages to which they remove frequently to get rid of them, and not withstanding all their precautions, they never Step into our hut without leaveing Sworms of those troublesome insects. Indeed I scercely get to Sleep half the night Clear of the torments of those flees, with the precaution of haveing my blankets Serched and the flees killed every day. The 1s[t] of those insects we Saw on the Collumbia River was at the 1s[t] Great falls–

Day 21—30 December 1805. This evening Clark sighed four words of triumph: “our fortification is Completed,” adding a cheerful aside: “this day proved to be the fairest and best which we have had since our arrival at this place.” He signed off with a satisfied Clarkian chuckle: “only three Showers dureing this whole day.”

Day 22—31 December 1805. But there was still a little more important work to do for the men’s comfort and convenience. Sgt. Ordway reported, “we built a box for the centinel to Stand in out of the rain dug 2 Sinques” or latrines, which would have been out beyond the “water gate.” Some Wahkiakums arrived today from upriver, from whom Clark bought some wapato, a couple of mats, and “about 3 pipes of their tobacco in a neet little bag made of rushes.” Finally, he added a footnote to their residency in Fort Clatsop:

With the party of Clât Sops who visited us last was a man of much lighter Coloured than the natives are generally, he was freckled with long duskey red hair, about 25 years of age, and most Certainly be half white at least, this man appeared to understand more of the English language than the others of his party, but did not Speak a word of English, he possessed all the habits of the indians.

If Clark’s estimate of the man’s age was accurate, it would appear that there were English-speaking fur traders on this part of the Pacific coast around 1780, twelve years before the American Robert Gray became the first man ever to enter the Columbia River estuary. It appears that no one has yet successfully explained this historical paradox.

Fort Clatsop is a High Potential Historic Site along the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail managed by the U.S. National Park Service. The site is managed by the Lewis and Clark National and State Historic Parks.—ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | In parts of 18th-century Britain, and among American Colonists and later immigrants who came from certain places in the British Isles, speakers typically elided the rhotic sound when it occurred before a consonant. In his phonetic spelling of “boards” (boads), William Clark clearly wrote an /a/ in place of an /r/, and probably uttered it as the unstressed neutral vowel now called a schwa (printed as ə; for pronunciation of the symbol see Wikipedia, s.v. Schwa). The substitution of the schwa for an /r/ is still characteristic of the speech of New Englanders from southern Massachusetts to New Hampshire. Dictionary of American Regional English, s.v. “board.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peter C. Welsh, “Woodworking Tools, 1600-1900,” in Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, Paper 51. Project Gutenberg EBook #27238; release date, November 12, 2008. |

| ↑3 | Jackson, Letters, 1:83. More expensive laces made of tape instead of rope were sometimes used as seats in stagecoaches to relieve passengers from painful jostling on rough roads. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.