“our trio of pests still invade and obstruct us on all occasions, these are the Musquetoes eye knats and prickley pears, equal to any three curses that ever poor Egypt laiboured under, except the Mahometant yoke.”

Barbary Coast Pirates

Piracy—robbery, kidnapping or physical violence on or from the sea, committed by independent, often unsanctioned parties of rogue sailors upon defenseless ships or coastal populations—may have begun soon after humans learned how to build seagoing boats, and how to use them to exchange valuable goods with distant tribes and nations, and how to turn them into instruments of intimidation. Historical records reaching back several thousand years BCE indicate that it has cropped up now and then, and prevailed for various periods of time, in almost every populated corner of the globe. In his essay De Officiis (“On Duties”), Marcus Tulius Cicero (106-43 BCE)—in whose writings Jefferson and many other leaders of the Enlightenment found affirmation and inspiration—warned that “a pirate is not counted as an enemy proper, but is the common foe of all. There ought to be no faith with him, or the sharing of any sworn oaths.”[1]M. T. Griffin and E. M. Atkins, eds., Cicero: On Duties (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 141

The Vikings committed piratical assaults throughout the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries. Piracy on the Mediterranean Sea gained momentum during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when Ottoman rulers in Constantinople (today’s Istanbul) began licensing owners of galleys called corsairs to seize foreign ships, confiscate their cargoes, and sell their officers and crewmen in the slave markets. The most notorious brigand of all was an Ottoman known as Khayr ad-Din (d. 1546) or, more infamously, as “Barbarossa, that distinguished scourge of mankind.”[2]“General Description of the Country of Algiers,” The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository, new series, vol. 2 (January 1797), 40.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, control of Mediterranean waters and all ports on the north coast of Africa was in the hands of the governors of Tripoli (today’s Libya), Tunisia and Algeria. All three were nominal regencies of the Ottoman Empire, but they exerted an indepen-dence that sometimes rankled the sultan at Constantinople. Morocco, an independent monarchy occupying the continent’s northwest coast, fell into line behind its neighbors. Together, the Barbary States controlled North Africa from the southern shore of the Mediterranean to the Sahara Desert, and from the Atlantic Ocean three thousand miles eastward to western Egypt,[3]In the Koran (Surah 47.4), Muhammed urged the capture of “those who are bent on denying the truth,” and their release only if they embraced Islam, or were ransomed. The Message of the … Continue reading constituting a region known as the Mahgrib[4]A highly instructive view of the First Barbary Coast War is contained in the U.S. Supreme Court case, Salim Ahmed Hamdan v. Donald H. Rumsfeld, et al. The brief is found in a PDF document titled … Continue reading.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the major European powers—England, France, Spain and Holland—had fought countless battles with pirates from the Barbary States, and more than 30,000 Christian slaves had been imprisoned in Algiers alone. Eventually, however, extortion proved to be the most potent tool in the pirates’ arsenal. European kingdoms and empires cheerfully paid the “tributes” that the outlaws extorted from them rather than tie up their own naval resources fighting the upstarts one corsair at a time, the year around. Even when “protected” merchant ships were captured “by mistake,” it was cheaper to reimburse their owners’ losses and pay the ransom for their crews than to storm the Barbary citadels.

Extortion

During the Colonial Era in America, British tributes—payments in jewels, pounds sterling, or naval stores such as ships and munitions—were supposed to protect American ships from harassment by the Barbary pirates, but the pirates could not be counted on to honor their part of any treaty for very long.[5]Paul Baepler, “The Barbary Captivity Narrative in American Culture,” Early American Literature, vol. 39, no. 2 (2004), 219-20. Martha Elena Rojas, “‘Insults Unpunished’: … Continue reading After Algerian pirates captured an American ship in 1678, churches in New Amsterdam (New York) voluntarily took responsibility for raising money for their sailors’ ransom. Twenty years later another ship was captured, and its crew was similarly ransomed. All this time, “captivity narratives” filled a popular niche in American literature. The sermons of the New England Puritan minister Cotton Mather (1663-1728) crystalized the underlying religious conflict between the crescent and the cross that motivated the “Hellish Pirates.”[6]The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1791), 50. In British and American literature throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, an adherent of the Mohammedan faith … Continue reading By the end of the eighteenth century, American readers were ready for ever deeper insights into the exotic culture of the “Mahometans.” With increasing frequency, popular magazines published items like Voltaire’s “Anecdote of a Young Mussulman,”[7]All but one of the crew members, that is. Peter Lisle, a Scottish deckhand on the Franklin, had already chosen the proffered alternative to slavery (see note 3 above) and “turned Turk,” … Continue reading while religious periodicals such as the Christian Observer often followed the fortunes of missionary outreach on the Barbary Coast.

Immediately after the American Colonies declared their independence, British authorities made it a point to notify the Barbary states that her former possessions in America were no longer protected under British treaties with the Barbary states. The governors were delighted; American merchantmen were distraught. The landowners who grew the grain, milled the flour, sawed the lumber, salted the fish or cured the tobacco that sold so well in Mediterranean ports, were facing ruin. So were American apothecaries and physicians who needed North African asafetida, tragacanth, opium, or Tripoli vitriol (sulfate of copper or iron).

Payoffs

In October of 1784, Moroccan pirates seized the American merchant ship Betsey, not for its commercial value but as a hostage to force the United States to send their bashaw the consul that had been promised in 1778. Through intercession by the Spanish government, the Betsey and her crew were released within a year.[8]Gardner W. Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs, Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1905), 13-14. Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 … Continue reading In July of 1785, Algiers declared war on the U.S. merely to please British interests, who sought to eliminate competition by scaring American traders out of the Mediterranean. Soon Algerian corsairs captured two more small American ships. The schooner Maria of Boston was overtaken off Cape St. Vincent, Portugal, and the Dauphin of Philadelphia 150 miles west of Lisbon.[9]Adams to Jefferson, 6 June 1786. Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 1:133. Adams was quoting Charles Gravier, count … Continue reading Jefferson and John Adams, the U.S. ministers to France and England respectively, were directed to negotiate a resolution with the Algerian authorities, an assignment complicated by the fact that, as Adams wrote to Jefferson, “Avarice and Fear are the only Agents at Algiers.”[10]Kenneth Morgan, Bristol and the Atlantic Trade in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 201. The dilemma they faced was that, on the one hand war would involve the expense of building a navy large and powerful enough to convoy American merchantmen into the Mediterranean; it would also drive up insurance rates, or even invalidate insurance entirely, on ships and cargoes of traders venturing into the danger zone.[11]James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 11 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902-04), vol. 1, parts 1 and 2. … Continue reading But subsidizing the pirates of one of the states would only encourage the others to demand equal or even higher payoffs. Moral and ethical issues aside, which was the less expensive option? Adams, in tune with American popular opinion as well as with many members of Congress, considered it cheaper in the long run to avoid war by paying for peace. Jefferson, despite his commitment to reducing the standing army and navy to minimum levels, preferred to stand up to all of the pirates. Adams prevailed, and Congress paid.[12]Allison, The Crescent Obscured, 10.

President Washington had similarly dealt in a conciliatory manner with the four Barbary states, and especially Morocco and Algiers, during his administration (1789–1797). On 8 December 1795, he announced to both houses of Congress: “A letter from the Emperor of Morocco announces to me his recognition of our treaty made with his father, the late Emperor, and consequently the continuance of peace with that power.”[13]President Washington’s Seventh Annual Message. Yale Law School, The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, The Barbary Treaties, … Continue reading During John Adams’s presidency (1797-1801) a “peace” treaty with the bashaw of Tripoli was signed, and a frigate was built for the dey of Algiers (named the Crescent) in expiation for the United States’ late payment of the stipulated tribute. The dey would have been delighted with the gift; round-bottomed Western sailing vessels were faster and more maneuverable, especially on the open seas, than the slow, clumsy galleys that had made up most of the pirates’ navies, with their double banks of oars stroked by prisoners and slaves. The only disadvantage of the large and powerful American frigates was that they were difficult to navigate through the shallow, rocky coastal waters, especially in the Bay of Tripoli.

Lewis’s “Mahometant yoke”

Figure 2

Burning of the Frigate Philadelphia in the Harbor of Tripoli

16 February 1804

U.S. Naval Academy Museum Collection. Thomas Moran (1829-1901), Oil on canvas (1897). Original size, 60 x 42 in.

Under cover of darkness on 16 February 1804, Lieutenant Stephen Decatur crept into the bay of Tripoli and boarded the Philadelphia with a force of nearly 70 volunteers, set fire to her, thus robbing the Tripolitans of the pleasure of her. At left foreground is the Tripolitan ketch[14]The ketch was a common broad-beamed, two-masted vessel on the Mediterranean. that the US schooner Enterprise had captured on 23 November 1803, and Decatur had renamed Intrepid, under full sail before an offshore breeze, heading back to the Enterprise for safety.

The Philadelphia‘s surgeon, Dr. Cowdry, who was allowed the freedom to care for the captive crew, observed that “the Turks appeared much disheartened at the loss of their frigate.” Their carpenters were repairing it, and it was being fitted out to be the most powerful warship in their fleet.

Who can say how much of this history Lewis might have known before he walked into the president’s house that April day? We only know that news about events in the capitols of the Barbary states had been reported in the American periodical press for many years, especially in the Christian missionary media, which Lewis, as a Deist, would have been inclined to ignore. Nevertheless, the fruits of the long history of the Barbarians’ brand of terrorism were piling up at Thomas Jefferson’s feet, and perforce at Lewis’s too. For the next twenty-three months, until he left Washington City in mid-March of 1803 for Harper’s Ferry, Lancaster, Philadelphia and points west, he was almost as close to the front lines of America’s first intercontinental War as was his friend and commander-in-chief.

Beyond his astute summary of the varied qualifications and political loyalties of the American army’s officers, which we have in his own hand [Lewis’s Report on Army Officers], history has left us no more than a few minor details concerning Meriwether Lewis‘s day-to-day responsibilities during his twenty-three-month tenure as the president’s secretary. Of course, Jefferson’s personal understanding of the Middle East and the Barbary States reached back to 1784 at least, and considering his reading habits, his personal library, and his astuteness as a statesman and philosopher, it is reasonable to suppose that he shared with Lewis as much of his background on the subject as circumstances demanded and time allowed. For our purposes, there are two major information sources from which we may sketch a detailed impression of the Barbary War from Lewis’s perspective that might have justified an epithet such as “the Mahometant yoke.” One of them comprised the first two of Jefferson’s Annual Messages to Congress. The other was Washington City’s tri-weekly newspaper, The National Intelligencer (Figure 3), in which not only were the Messages published, but also some of the ancillary documents that Jefferson provided Congressmen to enhance their understanding of the issues raised by the unexpected threat and ensuing conflict.

We shall enter the story at the point where John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were directed by President George Washington to deal with a specific problem on the Barbary Coast. It seems reasonable to suppose that Jefferson would have filled Lewis in on the substance of their experiences too.[15]The full story of the conflicts between the United States and the four Barbary states is well told from various perspectives in the following books: Gardner W. Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary … Continue reading

Proposals

For ten years, beginning with its first issue on 31 October 1800, the four-page, tri-weekly National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser of Washington City, edited by the high-minded ex-Philadelphian Samuel Harrison Smith, served as the semiofficial outlet for the administration’s official papers and Congressional debates, verbatim. Jefferson’s annual addresses were printed in it, along with the letters, reports and other documents that the president had given to Congress at the time his speech was read.

The circulation of the National Intelligencer during its early years is unknown, but at the turn of the new century the average run for the most popular newspapers was about six or seven hundred per issue. However, each copy was normally read by many additional readers, especially in coffee houses, taverns, and in “reading rooms” that maintained files of newspapers from all parts of the country.

At that time, when newspapers commonly depended upon one another for news outside the region served by any single paper, the National Intelligencer quickly became the primary source for objective, up-to-date reports of political news from Washington. It was Jefferson’s only direct link with the people.[16]Frank Luther Mott, American Journalism; A History, 1690-1960 (New York: Macmillan,, 1962), 176-77. William E. Ames, “The National Intelligencer: Washington’s Leading Political … Continue reading

The first mention of Tripoli appeared in the 3 January 1801 issue, with the report that the House of Representatives had recommended a budget to continue the hiring of consuls to be stationed in each of the four Barbary States. The first references to the threat of open conflict with any of the States were contained in several documents published in the National Intelligencer on 29 May 1801.

Following the tentative and unrequited post-Revolutionary efforts to establish workable U.S. relations with the Barbary States—Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Tripoli—and after the resolutions of the minor Moroccan and Algerian crises in 1784-85, John Adams had an unexpected encounter in 1786 with Abdrahaman, “a universal and perpetual Ambassador” from Tripoli.[17]There is also a city named Tripoli in Lebanon, in the Levant—the countries at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. The Tripoli referred to in this essay is the capitol of the largest and mostly … Continue reading Abdramahan knew a great deal about the young United States, and acknowledged that it was a very great country. But, he told Adams bluntly, “Tripoli is at War with it.” Adams, with gentlemanly restraint, answered that he had never heard of that. Nevertheless, said His Excellency, “there must be a Treaty of Peace.” War was the only alternative. “The Turks and Africans were the souvereigns of the Mediterranean,” Adams continued, quoting Abdramahan, “and there could be no navigation there nor Peace without Treaties of Peace. . . . America must treat with Tripoli and then with Constantinople and then with Algiers and Morocco.” The ambassador was “more ready and eager to treat than I was as he probably expected to gain more by the Treaty,” Adams observed. He ended his account of the meeting with a mixture of dismay and amusement. It was “very inconsistent with the Dignity of your Character and mine, but the Ridicule of it was real and the Drollery inevitable. How can We preserve our Dignity in negotiating with Such Nation? And who but a Petit Maitre [a fop or fool] would think of Gravity upon such an occasion.”[18]Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters (2 vols.; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 1:121-23. He simply couldn’t make himself take the Barbary satraps seriously.

As a pragmatist, Adams was convinced that the only viable course of action for the United States was to purchase treaties—to buy peace—because all European countries did so, and because he believed that American citizens would not foot the bills for a war, and for that reason Congress would not authorize one. To Jefferson, however, the idea of paying for peace was repugnant. War was inevitable. At length he presented a proposal to Congress outlining “Means which the Congress may make use of, in order to force the Regencies of Barbary to make peace with them.”[19]The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, ed. Barbara B. Oberg and J. Jefferson Looney (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008). Canonical URL: … Continue reading His plan drew no comment, perhaps because it was ill-considered. He recommended treatment of the Barbary States on their own terms—to sell captured Turks on the slave market at Malta, for example. Furthermore, he acknowledged the Ottoman sultan at Constantinople as the ruler of the regencies, when in fact the regents had been ignoring or defying the Porte since the end of the 16th century, except when it was obviously to their advantage to acquiesce.

Peace Payments

Yusuf Karamanli, the bashaw of Tripoli, was ambitious. He quarreled with his father, murdered one of his two brothers and, in 1790, usurped the office of bashaw[20]Bashaw, later spelled pasha, was a Turkish title for a provinicial governor. Also bey and dey, essentially synonyms, were variously applied. Bobba Mustapha was the Dey of Algiers; Hamuda was the Bey … Continue reading that rightly belonged to the other. Determined to increase the power of Tripoli to equal that of the other three Barbary States, he negotiated a treaty with the United States in 1796. Treaties of “peace and friendship” were signed with Morocco in 1786 and Algeria in 1795; U.S. Consul Joel Barlow signed one with Tunisia in 1797. Tripoli signed a Treaty of Friendship and Amity with the United States in 1796. From the American perspective, the main purpose of each of those treaties was to insure that American merchant ships plying the Mediterranean Sea would be safe from attacks by pirates from the four Barbary states. To the governors of those states, however, a treaty was a flexible weapon calculated to force “Christian” nations to send representatives to each of them, whom the beys, deys and bashaws would systematically manipulate into giving them cash, personal gifts, and naval supplies from their respective countries. The naval supplies could be used to strengthen the terrorists fleets of corsairs, as pirate ships were called, and the noose of intrigue and intimidation was complete.

Karamanli spelled out his demands in Article 10 of his treaty:

The money and presents demanded by the Bey of Tripoli as a full and satisfactory consideration on his part and on the part of his subjects for this treaty of perpetual peace and friendship are acknowledged to have been received by him previous to his signing the same, according to a reciept which is hereto annexed, except such part as is promised on the part of the United States to be delivered and paid by them on the arrival of their Consul in Tripoly, of which part a note is likewise hereto annexed. And no presence of any periodical tribute or farther payment is ever to be made by either party.[21]“The Barbary Treaties 1786-1836,” in The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy (Yale Law School: Lillian Goldman Law Library), “Treaty of Peace and Friendship, … Continue reading

In the Receipt—merely “on account of the peace concluded with the Americans”—Karamanli specifically demanded, up front, the equivalent of 40,000 Spanish dollars, and “presents” consisting of thirteen gold, silver, and “pinsbach” watches; three diamond seal rings, another of sapphire, and one with a watch in it; 140 “piques of cloth”; and four ankle-length brocade garments called caftans.[22]Barlow’s translation is open to interpretation. “Pinsbach,” a word of unknown meaning now, was Barlow’s transcription of the Arabic word tumb~k, an alloy of copper and zinc. … Continue reading Presumably those items were for the bashaw himself and his nearest associates. Jussuf, the “Bey whom God Exalt,” and Joel Barlow both signed the Receipt.

The “exception” was a Note appended to the treaty, which stipulated that when the American consul resumed his residency at Tripoli he was to present the bey with the equivalent of 12,000 more Spanish dollars, and “naval stores” consisting of five 8-inch braided rope hawsers; three 10-inch braided rope cables; 25 barrels of tar, 25 of pitch, and 10 of rosin; 500 pine and 500 oak boards; 10 masts; 12 yard-arms; 50 bolts of canvas; and 4 anchors. The Note ends with a confirmation of Article 10: “And no farther demand of tributes, presents or payments shall ever be made.” It was signed and dated at Tripoli on 3 June 1796, and ratified by Congress on 10 June 1797.[23]Both Receipt and Note may be seen at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/bar1796t.asp#art1 (accessed 12 August 2009).

That should have been the end of it, but when Consul Cathcart arrived in Tripoli on 5 April 1799, he learned that some of the promised naval stores had been either lost or stolen en route, and Karamanli was angry about it. When the consul offered to pay him $18,000 in cash, the equivalent value of the missing goods, Karamanli stepped up the price a notch, demanding also the brig[24]A brig is a two-masted vessel with three or four square sails on each (mailsail, topsail, topgallant sail, and sometimes a small “royal” squaresail). It also carries a small fore-and-aft … Continue reading that he said William O’Brien, the U.S. consul to Algeria, had verbally promised him at the time the treaty was signed. Cathcart stiffened. He knew that extortion was the name of the game, that dissimulation and intimidation—lying and bullying—were the usual tactics, and that Karamanli and his cohorts considered themselves entitled to revise a treaty at will, for cause. (Cicero was right—pirates are faithless, and their contracts are worthless.) But Yusuf backed down and settled for Cathcart’s offer.

Consequences

Come May of 1800, Yusuf was in a snit again. On the 25th he wrote a mincing letter to President John Adams, ending it with a weasel-warning:

You will . . . endeavor to satisfy us by a good manner of proceeding. We on our part will correspond with you, with equal friendship, as well in words as deeds. But if only flattering words are meant without performance, every one will act as he finds convenient. We beg a speedy answer, without neglect of time, as a delay on your part cannot but be prejudicial to your interests. In the mean time we wish you happiness.

But what was the problem? The Bashaw thought he had ample evidence that the United States had recently sent expensive presents to Algiers and Tunis, and he was sorry he had settled for that measly $18,000. But that wasn’t all.

Why do not the United States send me a voluntary present? They have acted with me as if they had done everything against their will. . . . I have the mortification to be informed that they have now sent a ship load of stores to Tunis, besides promising a present of jewels, and to me thay have sent compliments. But I have cruisers as well as Tunis. . . . I am an independent prince as well as the Bashaw of Tunis, and can hurt the commerce of any nation as much as the Tunisians.

The bashaw was mistaken, Cathcart replied. The U.S. had given nothing to either Tunis or Algiers that was not specified in their treaties. Furthermore, no American consul was empowered to give presents of any kind to anyone, “it being incompatible with our form of government, the funds of the United States not being at the disposal of the president until an appropriation is made by acts of the legislature.” Yusuf had no comment.

In that same issue of the National Intelligencer appeared an extract of a later letter from the consul at Tripoli.[25]Jefferson had Karamanli’s letter and Cathcart’s commentary published in the National Intelligencer on 6 January 1802, along with various other documents illustrating the issues he brought … Continue reading Under the dateline 18 October 1801, Cathcart recounted highlights of another meeting to which Karamanli had recently summoned him. As if to confirm old Abdramahan’s asseveration, the bashaw pointed out that in order for peace to reign, “all nations pay me, and so must the Americans.” Cathcart patiently replied, “we have already paid you all we owe you and are nothing in arrears.” Yusuf countered, according to the consul, that America had indeed paid him for the peace, but had given him nothing to maintain the peace. Cathcart contended that “the terms of our treaty were to pay him the stipulated cash, stores, &c. in full[fillment?] of all demands for ever.” He patiently reminded the bashaw that the American government had faithfully met those stipulations. The Tripolitan was unmoved. He had recently seen an American frigate moored at Algiers, presumably to unload more presents. “Why do they neglect me in their donations?” he scolded. “Let them give me a stipulated sum annually, and I will be reasonable as to the amount.” The consul waded in again, but to no avail. “Paid I will be, one way or other,” snarled the bashaw. Then he delivered the ultimatum he had been nursing.

I now desire you to inform your government that I will wait six months for an answer to my letter to the President [of 15 May 1800]; that if it did not arrive in that period, and if it was not satisfactory, if it did arrive, that I will declare War in form against the United States. Inform your government how I have served the Swedes,[26]Yusuf Bashaw had recently declared war on Sweden, capturing several ships and imprisoning their crews, thereby forcing the Swedish authorities to to sign a treaty, pay a tribute of $250,000 including … Continue reading who concluded their treaty since yours; let them know that the French, English, and Spaniards, have always sent me presents from time to time to preserve their peace, and if they do not do the same, I will order my cruisers to bring their vessels in whenever they can find them.

Then he turned to his foreign minister, Sidi Mohammed Dghies, and informed him (in French) that his conversation with the consul was not private, and he wished the whole world to know of it. Furthermore, he whispered to Dghies that he hoped the United States government would continue to ignore him, since “six or eight vessels . . . would amount to a much larger sum than he ever expected to get from the United States for remaining at peace.”

Cathcart, pretending he had not understood the bashaw, pressed him to state his expectations . “I expect,” the governor told the consul,

when he sends his answers they will be such as will empower you to conclude [a treaty] with me immediately—if they are not, I will capture your vessels; and as you have fequently informed me that your instructions do not authorize you to give me a dollar, I will there[fore] not inform you what I expect until you are empowered to negotiate with me. But you may inform your President, that if he is disposed to pay me for my friendship, I will be moderate in my demands.

“The Bashaw then rose from his seat,” Cathcart reported, “and went out of the room, leaving me to make what comment I thought proper upon his extraordinary conduct.” The consul summarily rejected those “degrading, humiliating and dishonorable terms,” and hastened to convey them to the president and the secretary of the navy. He also circulated a letter to all other US. agents and consuls, urging them to warn all American merchants and masters of vessels that although the bashaw had set 22 April as the end of his waiting period, the Mediterranean Sea would not be safe for them after 22 March 1801, “as these faithless people generally commit depredations before the time or period allowed is expired.”

Americans’ main fear was that the other three Barbary States were lurking beyond the horizon, just waiting to see what the outcome would be with Tripoli. Consul William Eaton described the Bey Hamuda of Tunis as “a man of good understanding and a mild character; but he is artful and avaricious,” seldom assaulting a Christian without first conceiving a pretext; and never in the face of superior force and audacity. Eaton regretted that he didn’t have the opportunity to impress upon Hamuda a clear understanding of the strength and energy of the government of the United States.[27]“Extract of a letter from the American consul at Tunis” to a friend in Springfield, Massachusetts, National Intelligencer, 23 September 1801, p. 2.

Richard O’Brien, the U.S. Consul at Algiers, formerly captain of the merchantman Dauphin out of Philadelphia, had gained firsthand experience with Algerian pirates during his eleven years as a slave following the capture of his ship off the coast of Portugal in July of 1785. In 1802 he reported that the Bashaw of Tripoli had claimed never to have “made reprisals on any nation, or declared war but in consequence of their promises not being fulfilled, or for want of due respect being shewn him.”[28]Extract of a letter from Richard O’Brien dated 12 May 1800, accompanying the president’s message to Congress of Dec. 8, 1801. National Intelligencer, 6 January 1802, p. 1. Clearly, for a pirate the outcome was open-ended.

Outrage

Reports such as these inspired outrage and disgust from all quarters of Jefferson’s administration, from the electorate, and especially from U.S. consuls in the Europe and the Middle East. William Eaton wrote to Secretary of State John Marshall, vigorously deploring the U.S. government’s willingness to kowtow to the pirates: “Genius of My Country! How are thou prostrate! Has thou not yet one son whose soul revolts, whose nerves convulse, blood vessels burst, and heart indignant swells at thoughts of such debasement?”[29]Eaton to Marshall, 11 November 1800, United States Navy, Office of Naval Records, Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers (6 vols., Washington, DC, 1939-44), … Continue reading Ten days later, the editor of a deist[30]See also Deists in the Wilderness. newspaper in New York City expressed a somewhat more optimistic opinion: “The day we expect will soon come when the great nation will chastise the African pirates, and open the Mediterranean to all nations, without paying fees or tributes to the petty tyrants of Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.”[31]The Temple of Reason, Vol. 1, (22 November 1800), p. 22. In September of 1801 Eaton dished out another jeremiad in a letter to a friend in Washington:

Why . . . should we come, cap in hand, and kiss the feet of these pitiful savages?—if once paying and once stooping would ensure us a permanent peace, we might submit for once; but this is not enough; these pirates are insatiable as the grave, and if we continue to countenance and feed their pretensions, the revenue of the United States will be inadequate to satisfy their avarice. . . . Until we alter our mode of negociation here, these Beys will consider as the result of fear what they should be taught to consider an act of grace.[32]Eaton to a friend in Springfield, Massachusetts; dateline Tunis, 14 April 1801. National Intelligencer, 23 September 1801, p. 1.

Strong words strengthened as the insults festered. Consul-General Humphreys wrote to the Secretary of State in April of 1801: “To chastise that haughty but contemptible power [Tripoli] which now dares first to insult us by its aggression would certainly serve, not only as a salutary example to the other piratical states, but it would produce an almost incalculable effect in elevating our national character in the estimation of all Europe.”[33]National Intelligencer, 29 May 1801, p. 1. Anybody could see that.

Acts of War

Despite Yusuf Karamanli’s promise not to seize any American vessels until after the 40-day extension of his amnesty expired, American merchant-men persisted in tempting fate. Therefore, on 2 June 1801, Cathcart wrote to Consul Thomas Appleton at Leghorn, Italy, enumerating the possible consequences. He noted, however, that Karamanli’s naval force was pitifully inadequate for serious warfare. “The whole force of Tripoli,” he said, “consists of seven sail of vessels, carrying 106 fours [four-pounder guns], sixes and nines, and 840 men, very badly equipped. They have more vessels, but have not people enough to man them.”

The flagship of the Tripolitan squadron was a captured American-built ship under the command of the Scottish-American renegade, Peter Lisle, alias Murad Rais, who was, said Cathcart, “a reputed coward; seldom goes near a vessel that looks warm [heavily armed].”[34]Leghorn, Italy, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801, p. 3. For comparison, the Algerine navy consisted of only “five vessels from 4 to 34 guns, and one 44 building.”[35]National Intelligencer, 26 June 1801, p. 3. Early in January of 1802, James Simpson pointed out that the Moroccan navy was even less of a threat. “At this time,” he wrote, “Muley Soliman has not a single vessel of war afloat; at Salee two frigates of about 20 guns are buiilding, and may probably be launched next Spring, but he is in want of many stores for them ere they can be sent to sea. At Teautan, they have lately patched up an old half galley, to carry two bow guns and fifty men, but, if I am to judge from her appearance last May, she is scarce fit to go to sea. This is all the navy.”[36]Salee, now Salle, Morocco, is a port on the Atlantic coast, 150 miles south of Gibraltar. Teautan, now Tetouan, is approximately 35 miles south of Gibraltar on the Mediterranean coast. A “half … Continue reading

European and American regulations concerning insurance coverage played into the scoflaws’ hands. Venture capitalists who backed ships, crews and cargoes had to protect their investments with insurance. But if a merchant captain resisted a piratical assault with force, that was an act of war, which would invalidate the insurance policy. Given those facts, the pirates’ brazen assaults were fully adequate when they worked. Cathcart, addressing naval vessels, not merchantmen, described them:

Their mode of attack is first to fire a broadside, and then to set up a great shout, in order to intimidate their enemy—they then board you, if you let them, with as many men as they can, armed with pistols, large and small knives, and probably a few with blunderbusses. If you beat them off once, they seldom risk a second encounter, and three well directed broad-sides will insure you a complete victory[37]Cathcart to Thomas Appleton, Leghorn, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801.

In early December of 1800, several American magazines and newspapers published a summary of the pirates’ spoliations during the previous two years. A total of at least 192 ships belonging to merchants from Naples, Sicily, Malta, Greece, England, France, Holland and Denmark had been captured by Algierian, Tunisian, and Tripolitan corsairs. Tripoli alone had captured 24 sail of Swedes. All of the bottoms and cargoes, collectively valued at millions of dollars, had been confiscated, and their crews condemned to slavery. The Danish governent was even forced to pay the Dey of Algiers a total of $100,000 just for causing an Algerine corsair to be wrecked on a shore near Tunis.[38]Salem (Massachusetts) Gazette, vol. 14, issue 972, 12 December 1800), p. 3. William Cathcart to Thomas Appleton, Washington City, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801, p 3.

Bainbridge’s Humiliation

Figure 4

Lieutenant William Bainbridge, USN

(1774-1833) at age 24

U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph, #NH 551541. Miniature, Artist unknown

Bainbridge’s first command was the brig Norfolk during the naval Quasi-War with France in 1798-1800. In 1801 he was given command of the frigate Philadelphia, which ran aground on a reef while chasing a corsair through Tripoli Bay. He and his crew of 307 officers and men were captured, and spent the rest of the First Barbary War as prisoners of Yusuf Bashaw Karamanli. Tripolitans seized the wrecked frigate and commenced refurbishing it into a warship of their own. Bainbridge suffered much criticism for his conduct in that incident, but redeemed himself in the War of 1812 as captain of the 44-gun frigate USS Constitution (Figure 6) by sinking the 38-gun British HMS Java.

William Bainbridge (1774-1833) was 26, the same age as Lewis, in 1800 when he was given command of the 24-gun sloop George Washington, which became the first American man-of-war to enter the Mediterranean and dock at Algiers. Thoughtlessly, he dropped anchor within range of the harbor fortress’s cannons, and before he could weigh anchor to depart, the Dey forced him to agree to carry a million-dollar cargo of gifts to the Grand Seignior of the Ottoman Empire, threatening, in case of refusal, “war to the United States, and slavery to the officers and crew of the George Washington.” The voyage, the dey insisted, was to be considered as a favor granted by the United States. Young Bainbridge was in a tight spot. “We had only to choose between compliance and slavery,” one of the ship’s officers recalled.[39]National Intelligencer, 24 December 1800, p. 3. On 15 October 1800, Bainbridge’s Washington set sail—under Algier’s green flag for protection from other pirates—and headed eastward on a 1,600-mile forced voyage. They wended their way among the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, past the Dardenelles and through the Sea of Marmara to Constantinople (today, Istanbul) on the Bosphorus Strait. The Washington‘s crowded decks carried one hundred male and female Negro slaves and a menagerie of wild animals from the heart of Africa; her hold was loaded with unnamed “funds and regalia.”

Bainbridge bluffed his way past the suspicious Turkish watchdogs at the Dardanelles and arrived at Constantinople on 9 November. The guards in the harbor there had never heard of a country called the United States. Bainbridge explained that it was part of the New World discovered by Columbus, which satisfied his inquisitors and permitted him to take a berth at the docks.

The young captain’s personal humiliation was deepened as soon as news of his unscheduled and, from the Amerian government’s point of view, altogether illegal voyage reached Jefferson’s Secretary of State, James Madison. Madison wrote to Consul James O’Brien at Algiers: “Whatever temporary effects it may have had favorable to our interests, the indignity is of so serious a nature, that it is not impossible that it may be deemed necessary on a fit occasion to revive the subject.”[40]James Madison to William O’Brien, 20 May 1801; National Intelligencer, 29 May 1801, p. 1. Evidently it never came up again.

Of course, the blustering Barbary princes had their own problems. Yusuf Karamanli, who had quarreled with his father, murdered one of his two brothers and usurped the throne that rightly belonged to the other, was unpopular with his people. The ravages of black death and the effects of drought and starvation made his position still more precarious. Morocco’s Muley Soliman had to put down a rebellion led by his nephew, in the process reportedly killing 8,000 of the rebel soldiers while taking only 200 prisoners.[41]National Intelligencer, 11 August 1802, p. 2. Worse yet, Muley had marched his army south through Morocco in late 1800, unaware from the outset that many of his men were already infected with the plague, which they unknowingly spread among their own people on their way through the land.

Congressional Update

President Jefferson had more than enough problems to face within or near his own borders beginning on the morning after his inauguration, 4 March 1801. There were treaties and trade agreements to be negotiated with Indian nations east of the Mississippi; problems with Spanish control of New Orleans; the precise location of the U.S.-Canada boundary (an issue that Lewis took part in by exploring the upper reaches of the Marias River) as well as the uncertainty of the boundary with Spain[42]See also The Freeman-Custis Expedition; the need for improvement and defense of U.S. Atlantic Coast ports. Geographically speaking, those matters were within easy grasp of the administration, whereas the evolving relations with Britain, France and Spain had to be dealt with at a distance. Most remote of all were the troublesome Barbary States, yet they were important to American commercial interests that the president had vowed to encourage and support; to simply ignore them could diminish foreign respect for the United States.

In his First Annual Message to Congress, copies of which Meriwether Lewis hand-carried to the House and Senate on 8 December, Jefferson summarized the major issues and events that he had dealt with during his first year in office, what he had done about them, and what the results had been. Concerning affairs in the Mediterranean Sea, he announced that Yusef Karmanli, the Bashaw of Tripoli—”the least considerable of the Barbary States”—had placed “arbitrary and unreasonable demands” on the United States, which Consul Cathcart had refused to countenance. “The style of the demand admitted but one answer,” the president said, so he sent a small squadron of three frigates and one support schooner to the scene, to protect American commerce against attack. “The measure,” he felt, “was seasonable and salutary.” The proof of that was demonstrated quickly and decisively.

First Battle

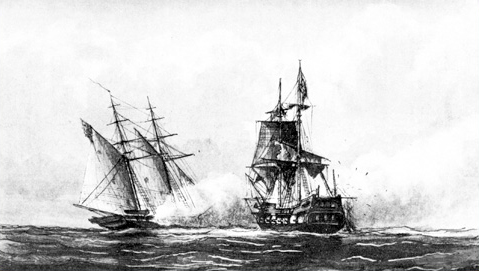

Figure 5

David Trounces Goliath

The USS Enterprise engages the corsair Tripoli

Collection of the U.S Navy. Drawing circa 1878 by Captain William Bainbridge-Hoff, a fourth-generation descendant of Commodore William Bainbridge (see Figure 4)

Captain Andrew Sterrett’s vessel, partially obscured by the smoke from a broadside of six-pounders, is identifiable as a schooner by the quadrilateral fore-and-aft gaff-sails flying from the two square-rigged masts. The pirates’ Tripoli, the heavier square-rigged vessel at right, has several sails in shreds, and splinters of wood have been blown from its starboard side above the waterline.

The first battle in the First Barbary War ended in a rousing victory that energized the navy, inspired Americans with patriotism and confidence in their country, and provided the navy and the nation with a new hero to cheer. Late in July of 1801, Captain Sterrett’s 12-gun escort and re-supply schooner Enterprise (then usually spelled Enterprize), manned by 94 officers and crewmen, was en route to Malta to refill her water barrels and those of the frigate President. From her stern flew a British ensign, either to give the impression that it belonged to a country that had paid the bashaw of Tripoli to keep his corsairs from harassing their ships, or else to decoy some prowling corsair into a fight. On 1 August they encountered the 20-gun Tripoli, manned by a crew of 90. The Tripoli‘s captain fell for Sterett’s deception and came alongside for a friendly chat. Sterrett quickly exchanged the Union Jack for the Stars and Stripes and initiated the fight by ordering the twenty Marines on board to open fire. The battle lasted three hours, with Sterrett successfully repelling his opponent’s efforts to board him—the pirates’ preferred hand-to-hand, deck-sweeping mode of assault. Twice the Tripoli’s rais, or captain, Mahomet Rous, feigned surrender by lowering his colors in an attempt to entice the Americans to board him so that his men could fight it out on their own decks. Sterrett avoided that trap, too. Finally Mahomet Rous, overwhelmed by the Americans’ superior seamanship and firepower, threw his flag into the sea in total surrender.

Sterrett inspected the defeated ship and found her “in a most perilous condition,” having received 18 cannonballs “between wind and water.” The carnage on board was dreadful. Twenty men had been killed and thirty wounded; among the latter were the captain and first lieutenant.[43]Dispatch delivered in person by Captain Sterret to Secretary of the Navy Smith, National Intelligencer, 18 November 1801, p. 2. “Between wind and water” meant that the 18 cannonballs had … Continue reading Consistent with the president’s orders, reiterated by Commodore Dale who was in command of the squadron, that prisoners and defeated vessels were not to be seized, Sterrett ordered his men to cut down the Tripoli‘s masts and throw overboard her guns and all other property of value. Then, having dismantled her of everything but a tattered old sail and a single spar, he let the Tripolitans make their way to the nearest port as best they could.

Jefferson was proud of his feisty little navy’s success in its first battle of the Barbary War—and so might Lewis have been. On the first of December the president personally wrote to Lieutenant Sterrett to express the “high satisfaction” that his victory had inspired in his countrymen. “Too long, for the honor of nations,” the president wrote, “have those barbarians been suffered to trample on the sacred faith of treaties, on the rights and laws of human nature!”[44]Thomas Jefferson to Andrew Sterrett, 1 December 1801. The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence, 1651-1827. http://memory.loc.gov/ (retrieved 20 October 2009. A week later he expressed similar feelings to both houses of Congress: “The bravery exhibited by our citizens will, I trust, be a testimony to the world that it is not the want of that virtue which makes us seek their peace, but a conscientiouis desire to direct the energies of our nation to the multiplication of the human race, and not to its destruction.”[45]James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Volume 1, Section 3: Thomas Jefferson.

On the other hand, the National Intelligencer reported on 18 June that Bashaw Yusef Karamanli, enraged at Reis Mahomet Sous’s failure in battle, had ordered the unfortunate pirate captain to be paraded through the streets of Tripoli on the back of a jackass to the site of his ultimate humiliation, a public bastinado.

Jolted by Yusef Karamanli’s quixotic declaration of war, Congress acted quickly to give the president authority to direct his commanders to take preemptive action toward any country that declared war on the U.S. On 6 February 1802, they passed “An Act for the Protection of the Commerce and Seamen of the United States against the Tripolitan Cruisers,” authorizing the president to direct the commanders of U.S. Navy ships to “seize and take prize of all vessels, goods and effects, belonging to the Bey of Tripoli, or to his subjects.” However, the taking of “prizes,” a standard policy of war, was impractical since it would have required escorting all such ships to American ports, and few if any Tripolitan vessels were seaworthy enough for that.

Reinforcements

On orders from secretary of the navy Robert Smith dated 13 July 1803, a squadron of nine warships, led by the frigate Constitution, was ordered to the Mediterranean Sea to protect American merchantmen from depredations by the Barbary pirates. The Constellation, armed with 36 guns, drew nearly 14 feet of water; the Chesapeake (rated 32 guns, but carried 51) drew 20 feet, the Adams (28 guns) nearly 11 feet; the John Adams (30 guns), almost 17 feet; and the New York (36 guns), nearly 12 feet. Support vessels included the schooner Enterprise, and the brigs Vixen, Argus, Nautilus, and Siren. The squadron was commanded by Commodore James Barron; Stephen Decatur, Jr., was his first lieutenant. They were under orders not to enter the bay at Tripoli because it was too shallow in many places for ships drawing twelve feet of water or more. The squadron also included the ill-starred 36-gun Philadelphia under the command of William Bainbridge.[46]The Constitution was the third of the six fast, easily maneuverable, heavily armed ships-of-the-line built at the urging of President George Washington to lead the new American Navy. She was launched … Continue reading

Jefferson’s second state-of-the-union message, delivered to Congress on 15 December 1802, contained several issues of greater moment than the shenanigans of the Barbary States. Spain’s sudden closure of New Orleans to American shippers was a serious threat to international commerce, but Spain’s subsequent retrocession of the entire Province of Louisiana back to France promised some improvement in that arena of foreign commerce. The president instructed James Monroe, his envoy to France, to explore the possibility of purchasing that port as well as western Florida. (Napoleon’s surprising offer to sell the entire Louisiana Territory to the United States was in the very near future.)

Far away, in the Mediterranean Sea, the Barbary War had been under way for more than a year, and initial fears seemed somewhat diminished.

There was reason not long since to apprehend that the warfare in which we were engaged with Tripoli might be taken up by some other of the Barbary Powers. A reenforcement, therefore, was immediately ordered to the vessels already there. Subsequent information, however has removed these apprehensions for the present. To secure our commerce in that sea with the smallest force competent, we have supposed it best to watch strictly the harbor of Tripoli. Still, however, the shallowness of their coast and the want of smaller vessels on our part has permitted some cruisers to escape unobserved, and to one of these an American vessel unfortunately fell a prey.[47]Thomas Jefferson: Second Annual Message to Congress, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jeffmes2.asp (accessed on 9 June 2018).

Subsequent events had justified the expectation that Algieria, Tunisia and Morocco would fall in line behind Tripoli. In September-October of 1802 there was a near-war with Morocco, partly as a consequence of Consul Simpson’s refusal to secure permission for a Moroccan ship to break the blockade of Tripoli harbor with a cargo of wheat for Yusuf’s starving people. Also, presumably to arm his new frigates, Soliman had invented a pretense for amending his 50-year treaty with the U.S., and asked Consul Simpson for 100 gun carriages—not guns, mind you, just carriages. He said he would pay for them. However, Simpson paraphrased the sultan, “should the government think well of making the Emperor of Morocco a present at this time, as a fresh proof of the friendship of the United States, . . . these carriages would be more acceptable to him than any thing else.”[48]Dateline Tangier, January 8, 1802; National Intelligencer, 24 December 1802. Relations with Morocco were in general disarray, Soliman having impulsively declared war on the U.S., but Simpson, understanding the politics of terrorism, confided to a friend: “I hope the gun carriages will come just in time to settle every thing, at least for some years, until they think of something else to ask for.”[49]Consul Simpson to Consul Gavino, dateline Tangier, September 27, 1802; National Intelligencer, 27 December 1802.

Jefferson’s phrase, “the smallest force competent” was a signal that notwithstanding the Barbary War, and consistent with his campaign vow, he was making a serious effort to keep expenses to a minimum; “to watch strictly the harbor of Tripoli” referred to a strategic blockade. Since the Algerian trouble in 1784-5, Jefferson had wanted to organize a perpetual blockade with the collaboration of Europe’s smaller nations. Most European countries were already paying tributes to the Barbary powers, so the American navy had to make do with a few passes of the entrance to the bay of Tripoli by a couple of well-armed frigates. That was effective enough, temporarily.

The American vessel that “unfortunately fell a prey” was the little 8-gun brig Franklin, captured on 17 June by a corsair that had recently slipped out of Tripoli and dodged the blockade.[50]Dateline Algiers, 30 June 1802; National Intelligencer, 6 October 1802, p. 3. The pirates released all of the crewmen who were not Americans, and by early October the captain and three captive seamen were ransomed by Consul O’Brien for $6,500. Thus there appeared to be a need for some small shallow-draft gunboats to beef up the blockade. The would involve some expense, although, the president reminded the congressmen, “the difference in their maintenance will soon make it a measure of economy.”

Informing Lewis

Jefferson directed the publishers of Philadelphia’s Aurora and Washington’s National Intelligencer to mail copies of their newspapers to Lewis in care of the military posts at Cahokia or Kaskaskia in the Illinois country, for six months beginning in mid-November of 1803. We can deduce from the context of the statement in the letter that his reason was to keep Lewis informed about the status of treaty negotiations for the purchase of Louisiana, and the timelines for taking possession of the territory. Lewis sent at least three newspapers across the Mississippi to Clark at Camp Dubois on 16 January 1804, but Clark’s journal entry for that date gives no hint as to any of the news they contained.[51]Moulton, Journals, 2:157. We don’t know all of the recollections of the first two years of the Barbary War Lewis might have recalled during his arduous journey to the mouth of the Columbia River and back. But he did tell us of one—the high nuisance quotient of the Barbary States.

Six days before the end of the expedition, at 11:00 on the morning of 17 September 1806, Lewis encountered his old friend Captain John McClellan and his party of traders outbound from St. Louis. Lewis wasn’t journaling, but Clark wrote a perfunctory recollection of the meeting:

This gentleman an acquaintance of my friend Capt Lewis was Somewhat astonished to See us return and appeared rejoiced to meet us. we found him a man of information and from whome we received a partial account of the political State of our Country, we were makeing enquiries and exchangeing answers &c. untill near mid night.[52]Ibid., 8:363.

He didn’t see any reason to list the specific portions of the “the political State” of the country they learned of, or what questions and answers they exchanged. Lewis might have asked who won the Tripolitan war. If he didn’t, then he would surely have heard some of the highlights after he reached St. Louis. If not there, then he could have gathered details little by little as he traveled eastward that fall. And we may suppose that Jefferson filled him in on more of the story when they sat down together in Washington City in January of 1807.

Lewis had been out of touch with all that was going on elsewhere in his country for the past twenty-eight months. What had he missed, specifically regarding the Barbary War?

First, the grounding and abandonment of the 44-gun frigate USS Philadelphia on an uncharted reef in Tripoli harbor on 31 October 1803, and the immediate enslavement of the 300 crewmen and officers, including Captain Bainbridge.

Second, the nighttime boarding and burning of what was left of the Philadelphia by young Lieutenant Stephen Decatur, Jr. and his 60 volunteers, thereby depriving Yusuf Karamanli of what would have become the finest pirate man-of-war afloat. Decatur’s daring escapade took place on 16 January, but the news didn’t reach Washington until mid-November.

Third, the self-commissioned “General” William Eaton, with a detail of six U.S. Marines, led a thousand-man force consisting of several hundred mercenaries, plus a large number of Tripolitan dissidents who were supporters of Yussuf’s deposed and exiled brother, Hamet, on a forced march of more than 500 miles from Alexandria, Egypt, to the Tripolitan provincial capitol at Derna (today called Darnah, in Libya). Eaton and his army followed a route that more or less closely paralleled the Mediterranean’s south shore, an arduous feat still memorialized today in the second phrase of the first line of The Marines’ Hymn.[53]Shortly after the First Barbary War ended in 1805, the words “To the Shores of Tripoli” were inscribed on the Marine Corps’ Colors. Following the Marines’ participation in the … Continue reading

There was a near-war with Morocco in late summer of 1803, when a Moroccan cruiser allegedly attacked a U.S. merchantman. In response, the frigates Constitution, New-York and John Adams (112 guns total), plus two schooners, were ordered to patrol the Moroccan coast.[54]National Intelligencer, 24 December 1802. On 23 November the Senate authorized hostilities against Muley Soliman’s gunboats, but by 5 December Jefferson could report to both houses that the sultan’s “misunderstanding” had been resolved, and that crisis was past.

Finally, Lewis might at least have heard from his friend McClellan that the Barbary War was history—that the “Mahometant yoke” had at last been lifted from American shoulders. Even before he learned of Lear’s success with the treaty, Jefferson had written to his old Virginia friend John Tyler that the “war” with Tripoli was merely a sideshow. Indubitably, however, it had been “seasonal and salutary.” There is reason, he wrote, “to believe the example we have set, begins already to work on the dispositions of the powers of Europe to emancipate themselves from that degrading yoke. Should we produce such a revolution there, we shall be amply rewarded for what we have done.”[55]Jefferson to John Tyler, 29 March 1805, in Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903), 11:69-70.

Heroes

In addition, Lewis may have gotten his fill of reports about the two new battle heroes the war had produced for Americans to admire. Against all odds, “General” Eaton returned home in the summer of 1807 to the huzzahs of a grateful populace. Americans embraced him as “a bona fide flag-waving, enemy-crushing American military hero. Not since the public had enshrined Stephen Decatur for burning the Philadelphia in Tripoli harbor had anyone been raised this high.”[56]Richard Zacks, The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, the First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805, (New York: Hyperion, 2005), 320. (Could that have been partly why Lewis complained to his good friend and confidant Mahlon, in November of 1807, that he himself “had never felt less like a hero than at the present moment”?[57]Meriwether Lewis to Mahlon Dickerson, 3 November 1807, in Jackson, Letters, 2:720.) Eaton’s campaign to win over the state of Tripoli for America, which reached the brink of success at the gates of the provincial palace at Derna, had actually been a fiasco, a Hydra-headed farce of hair’s-breadth brushes with disaster and ignominy, unexplainable goof-ups, dire misunderstandings, bureaucratic bungling, delayed supplies, misconceived military gambits, and hopeless personal indebtedness on Eaton’s part.[58]Zacks, 331-45. Clumsily but nonetheless surely, Lear snatched the victory out of Eaton’s hands at the last minute by secretly negotiating an end to the Tripolitan war. That treaty, signed on the deck of the USS Constitution while standing off the bay of Tripoli, left Yusuf Karamanli in control of the state but strongly encouraged him to give up piracy.

Aside from Joel Barlow’s insertion of his own gratuitous “Article 11” into the 1796 treaty with Tripoli, which was reiterated and expanded in the 1805 treaty, the shoving match that was given the legitimacy of a “war” by the Barbary pirates was not a religious crusade on the part of either Muslims or Christians. Tacitly, the Barbary states took prisoners under authority of Sur’ah 47.4 of the Qur’ãn,[59]“Now when you meet [in war] those who are bent on denying the truth, smite their necks until you overcome them fully, and then tighten their bonds, but thereafter [set them free,] either by an … Continue reading but their motivation was limited to base greed.

Lifting the Yoke

A ground-level view from the sidelines where Meriwether Lewis stood could have resembled a barroom brawl initiated by four unregenerate bullies intoxicated only by their own super-sized self images, flavored with avarice, and topped with insatiable appetites for power. On a less belligerent level, the whole story of this “war,” plus the several ensuing tussles with fear-mongering pirates on the Barbary Coast, until the final curtain fell in 1835, reads like a scenario for an opera buffa such as Jefferson enjoyed at the Comédie-Italienne the year before he left Paris.[60]Sandor Salgo, Thomas Jefferson, Musician & Violinist (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 24-25.

Those packs of Barbary dogs were merely pseudo-political nuisances, capable of getting in other peoples’ faces by day, and of keeping them awake with worry by night. They were more insidious than the cactuses that punctured the Corps of Discovery’s feet in the American west. More annoying than the eye-gnats. More persistent than the mosquitoes. Much more. For a few years at least.

If Lewis had published his own edition of the journals as he promised, he might well have revised his metaphor to read “the Barbary yoke.” In any case, the story of what was known by his detractors as “Jefferson’s War,” opens for us a narrow window on a little known but intriguing episode in Meriwether Lewis’s brief hitch as the President’s secretary.

Notes

| ↑1 | M. T. Griffin and E. M. Atkins, eds., Cicero: On Duties (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 141 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “General Description of the Country of Algiers,” The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository, new series, vol. 2 (January 1797), 40. |

| ↑3 | In the Koran (Surah 47.4), Muhammed urged the capture of “those who are bent on denying the truth,” and their release only if they embraced Islam, or were ransomed. The Message of the Quran, transl. Muhammad Asad (Bristol, England: The Book Foundation, 2003), 883-84 and notes 5-7. Perhaps because he knew that the Arabic language includes four characters that have no English equivalents, Thomas Jefferson taught himself to read Arabic so that he could properly study the Koran. Kevin J. Hayes, “How Thomas Jefferson Read the Qur’an,” Early American Literature vol. 39, no. 2 (2004), 247-61. |

| ↑4 | A highly instructive view of the First Barbary Coast War is contained in the U.S. Supreme Court case, Salim Ahmed Hamdan v. Donald H. Rumsfeld, et al. The brief is found in a PDF document titled Supreme Court of the United States. No 05-184. |

| ↑5 | Paul Baepler, “The Barbary Captivity Narrative in American Culture,” Early American Literature, vol. 39, no. 2 (2004), 219-20. Martha Elena Rojas, “‘Insults Unpunished’: Barbary Captives, American Slaves, and the Negotiation of Liberty,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 1, no. 2 (Fall 2003), 159-186. |

| ↑6 | The New York Magazine, or Literary Repository, Vol. 2, No. 1 (January 1791), 50. In British and American literature throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, an adherent of the Mohammedan faith was often referred to as a Mussulman. The name originated as a Persian word that evolved into the Arabic Muslim, which was the active participle of the verb aslama, meaning “to submit oneself to the will of God.” Mussulman may have become a surname during the early 16th century, when Mennonite missionaries in Switzerland converted to their brand of Christianity many Mohammendan (or Mahometan, as it was then commonly transliterated into English) families whose Moorish ancestors had settled in southern and central Europe beginning in the 8th century. The Mennonites’ firm commitment to nonviolence may have been one of the principal reasons for their appeal to Europeanized Muslims. J. C. Wenger, The Mennonite Church in America, (Scottdale, Pennsylvania: Herald Press, 1966). The first Mussulmans emigrated to the United States during the second half of the eighteenth century. The present author’s ancestors may have arrived in Virginia in the 1760s, perhaps 80 years after the first French Huguenots of his maternal lineage, including the Huguenot family Agée, stepped ashore in Virginia. The last pre-immigration Islamic branches in his family tree have not been identified. |

| ↑7 | All but one of the crew members, that is. Peter Lisle, a Scottish deckhand on the Franklin, had already chosen the proffered alternative to slavery (see note 3 above) and “turned Turk,” taking the name of a famous sixteenth-century Algerian pirate, Murad Reis; he consolidated his new allegiance by marrying one of Bashaw Yussuf Karamanli’s sisters. The Betsey was renamed the Meshuda, and refitted to serve as the 28-gun flagship of the little Tripolitan navy, with Murad Reis as its grand admiral. Above the Meshuda‘s stern Reis flew the flags of all the nations whose vessels he had captured, in order of their rank in his esteem; the old Franklin‘s colors were at the bottom. |

| ↑8 | Gardner W. Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs, Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1905), 13-14. Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World, 1776-1815 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 110. |

| ↑9 | Adams to Jefferson, 6 June 1786. Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 1:133. Adams was quoting Charles Gravier, count de Vergennes, the foreign minister who led the French alliance that helped the U.S. throw off British rule. |

| ↑10 | Kenneth Morgan, Bristol and the Atlantic Trade in the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 201. |

| ↑11 | James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 11 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902-04), vol. 1, parts 1 and 2. http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/gutbook/lookup?num=11314 and 10894 (retrieved 24 September 2009). |

| ↑12 | Allison, The Crescent Obscured, 10. |

| ↑13 | President Washington’s Seventh Annual Message. Yale Law School, The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy, The Barbary Treaties, 1786-1816,http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/bar1786t.asp (retrieved 14 October 2009). The treaty Washington mentioned was the Treaty of Peace and Friendship for a period of fifty years, which the Emperor of Morocco signed on 23 June 1786. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, U.S. ministers to London and France, respectively, negotiated an addition to the tenth article, in which the Moroccan emperor agreed to protect, as much as possible, any American ship in any of his ports from pursuit or engagement by any vessel whatsoever “belonging either to Moorish or Christian Powers with whom the United States may be at War . . . as we now deem the Citizens of America our good Friends.” The treaty was ratified by Congress and proclaimed on 18 July 1787. In July of 2009 Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton met with the Moroccan Foreign Minister Dr. Taie Fassi Fihri, praising Morocco as “one of America’s oldest and closest allies: in 1777″—it was 1778—”it became the first country to recognize the independence of the American colonies, and the Treaty of Friendship and Peace of 1787 between the United States and Morocco remains America’s longest-unbroken treaty.” “Morocco,” she declared, “has long partnered with the US to build bridges between the Islamic world and the West, as well as to combat acts of terrorism in the lawless regions of the Sahara.” http://prnewswire.com/news-releases/secretary-clinton-praises-morocco-for-longstanding-partnership-recognizes-moroccos-historic-role-in-combating-piracy-on-high-seas-61789582.html (retrieved 7 April 2015). |

| ↑14 | The ketch was a common broad-beamed, two-masted vessel on the Mediterranean. |

| ↑15 | The full story of the conflicts between the United States and the four Barbary states is well told from various perspectives in the following books: Gardner W. Allen, Our Navy and the Barbary Corsairs (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1905); Robert J. Allison, The Crescent Obscured: The United States and the Muslim World 1776-1815 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995); Joseph Wheelan, Jefferson’s War: America’s First War on Terror 1801-1805 (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2003); Richard Zacks, The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, the First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805 (New York: Hyperion, 2005). |

| ↑16 | Frank Luther Mott, American Journalism; A History, 1690-1960 (New York: Macmillan,, 1962), 176-77. William E. Ames, “The National Intelligencer: Washington’s Leading Political Newspaper,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Vol. 66/68 (Historical Society of Washington, D.C., 1966/1968), 73-74,159, 202-03. The advent of news services that could transmit information widely and instantaneously awaited the perfection of the electromagnetic telegraph in the late 1840s. |

| ↑17 | There is also a city named Tripoli in Lebanon, in the Levant—the countries at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. The Tripoli referred to in this essay is the capitol of the largest and mostly desert country in North Africa, now known as Libya. As early as 8,000 years BCE it was the homeland of Neolithic agricultural tribes who called themselves Berbers. In 1800 the Ottoman regency consisted of Tripolitania, Cyreniaca to the east bordering on Egypt, and Fezzan, a desert region bordering both on the south. |

| ↑18 | Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters (2 vols.; Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1959), 1:121-23. |

| ↑19 | The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, ed. Barbara B. Oberg and J. Jefferson Looney (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, Rotunda, 2008). Canonical URL: http://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/default.xqy?keys=TSJN-print-01-18-02-0139-0002 (accessed 20 Dec 2009). Original source: Main Series, Volume 18 (4 November 1790–24 January 1791). During the four-year war with Tripoli (1801-1805), Jefferson abandoned the measure-for-measure reaction, and rigorously observed the principles that he had established in the Constitution. |

| ↑20 | Bashaw, later spelled pasha, was a Turkish title for a provinicial governor. Also bey and dey, essentially synonyms, were variously applied. Bobba Mustapha was the Dey of Algiers; Hamuda was the Bey of Tunis; Morocco, not an Ottoman regency but an absolute monarchy, was headed by the emperor or Sultan, Muley Soliman. |

| ↑21 | “The Barbary Treaties 1786-1836,” in The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy (Yale Law School: Lillian Goldman Law Library), “Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Signed at Tripoli 4 November 1796,” http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/bar1796t.asp (Accessed 12 August 2009). |

| ↑22 | Barlow’s translation is open to interpretation. “Pinsbach,” a word of unknown meaning now, was Barlow’s transcription of the Arabic word tumb~k, an alloy of copper and zinc. Legal historian Hunter Miller’s notes on the treaty translation are to be found at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/bar1796n.asp (Accessed 12 August 2009). The noun piqué (pee-kay) denotes both a stiff, patterned cotton fabric and a shirt or other garment made of piqué. OED Online (2009), sense 5. |

| ↑23 | Both Receipt and Note may be seen at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/bar1796t.asp#art1 (accessed 12 August 2009). |

| ↑24 | A brig is a two-masted vessel with three or four square sails on each (mailsail, topsail, topgallant sail, and sometimes a small “royal” squaresail). It also carries a small fore-and-aft sail to improve the vessel’s maneuverability. The foremast is somewhat smaller than the mainmast. It also supports a jib sail, staysail, and flying jib, all attached to a long bowsprit. |

| ↑25 | Jefferson had Karamanli’s letter and Cathcart’s commentary published in the National Intelligencer on 6 January 1802, along with various other documents illustrating the issues he brought up in his second annual address to Congress. |

| ↑26 | Yusuf Bashaw had recently declared war on Sweden, capturing several ships and imprisoning their crews, thereby forcing the Swedish authorities to to sign a treaty, pay a tribute of $250,000 including ransom for 131 captives, and guarantee Tripoli an annuity of $20,000 for an indefinite period. |

| ↑27 | “Extract of a letter from the American consul at Tunis” to a friend in Springfield, Massachusetts, National Intelligencer, 23 September 1801, p. 2. |

| ↑28 | Extract of a letter from Richard O’Brien dated 12 May 1800, accompanying the president’s message to Congress of Dec. 8, 1801. National Intelligencer, 6 January 1802, p. 1. |

| ↑29 | Eaton to Marshall, 11 November 1800, United States Navy, Office of Naval Records, Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers (6 vols., Washington, DC, 1939-44), 1:397-98. |

| ↑30 | See also Deists in the Wilderness. |

| ↑31 | The Temple of Reason, Vol. 1, (22 November 1800), p. 22. |

| ↑32 | Eaton to a friend in Springfield, Massachusetts; dateline Tunis, 14 April 1801. National Intelligencer, 23 September 1801, p. 1. |

| ↑33 | National Intelligencer, 29 May 1801, p. 1. |

| ↑34 | Leghorn, Italy, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801, p. 3. |

| ↑35 | National Intelligencer, 26 June 1801, p. 3. |

| ↑36 | Salee, now Salle, Morocco, is a port on the Atlantic coast, 150 miles south of Gibraltar. Teautan, now Tetouan, is approximately 35 miles south of Gibraltar on the Mediterranean coast. A “half galley,” maybe 130 feet in length, is powered by 125 oarsmen; a 160-feet-long “full galley” uses 250 oarsmen on 25 pairs of sweeps. Dateline Tangier, 8 January 1802; National Intelligencer, 24 December 1802, p. 1. |

| ↑37 | Cathcart to Thomas Appleton, Leghorn, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801. |

| ↑38 | Salem (Massachusetts) Gazette, vol. 14, issue 972, 12 December 1800), p. 3. William Cathcart to Thomas Appleton, Washington City, 2 June 1801; National Intelligencer, 2 September 1801, p 3. |

| ↑39 | National Intelligencer, 24 December 1800, p. 3. |

| ↑40 | James Madison to William O’Brien, 20 May 1801; National Intelligencer, 29 May 1801, p. 1. |

| ↑41 | National Intelligencer, 11 August 1802, p. 2. |

| ↑42 | See also The Freeman-Custis Expedition |

| ↑43 | Dispatch delivered in person by Captain Sterret to Secretary of the Navy Smith, National Intelligencer, 18 November 1801, p. 2. “Between wind and water” meant that the 18 cannonballs had penetrated the corsair’s hull in the critical zone that is alternately wet and dry from the motion of the waves, and will take on water as the ship heels on first one side, then the other, while tacking into the wind. Admiral W. H Smyth, The Sailor’s Word-Book: An Alphabetical Digest of Nautical Terms (London: Blackie and Son, 1867), s.v. “Wind and water line.” |

| ↑44 | Thomas Jefferson to Andrew Sterrett, 1 December 1801. The Thomas Jefferson Papers Series 1. General Correspondence, 1651-1827. http://memory.loc.gov/ (retrieved 20 October 2009. |

| ↑45 | James D. Richardson, ed., A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, Volume 1, Section 3: Thomas Jefferson. |

| ↑46 | The Constitution was the third of the six fast, easily maneuverable, heavily armed ships-of-the-line built at the urging of President George Washington to lead the new American Navy. She was launched at Boston on 27 October 1797, nicknamed “Old Ironsides” during the War of 1812, and today is the oldest commissioned U.S. naval vessel still afloat. Rated at 44 guns, although she often carried as many as 50, she was manned by a crew of 450 officers and enlisted men, including 55 Marines and 30 boys. United States Navy Fact File. 7 July 2007. (Retrieved 10 October 2009). Second Annual Message to Congress, Avalon Project. |

| ↑47 | Thomas Jefferson: Second Annual Message to Congress, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jeffmes2.asp (accessed on 9 June 2018). |

| ↑48 | Dateline Tangier, January 8, 1802; National Intelligencer, 24 December 1802. |

| ↑49 | Consul Simpson to Consul Gavino, dateline Tangier, September 27, 1802; National Intelligencer, 27 December 1802. |

| ↑50 | Dateline Algiers, 30 June 1802; National Intelligencer, 6 October 1802, p. 3. |

| ↑51 | Moulton, Journals, 2:157. |

| ↑52 | Ibid., 8:363. |

| ↑53 | Shortly after the First Barbary War ended in 1805, the words “To the Shores of Tripoli” were inscribed on the Marine Corps’ Colors. Following the Marines’ participation in the U.S.-Mexican War of 1846-48, the phrase “Halls of Montezuma”—the Castle of Chapultepec—was added to their flag. The author of the Marine’s Hymn is unknown, but all three stanzas of it first appeared in print in 1918; in 1929 it officially became The Marines’ Hymn. The tune, with a few emendations to accommodate English prosody, is that of a song, “Couplets des Deux Hommes d’Armes” (Song of the Two Men-at-Arms), from an operetta, Geneviève de Brabant (Genevieve of Brabant) composed in 1867 by the French composer Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880). |

| ↑54 | National Intelligencer, 24 December 1802. |

| ↑55 | Jefferson to John Tyler, 29 March 1805, in Albert Ellery Bergh, ed., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association of the United States, 1903), 11:69-70. |