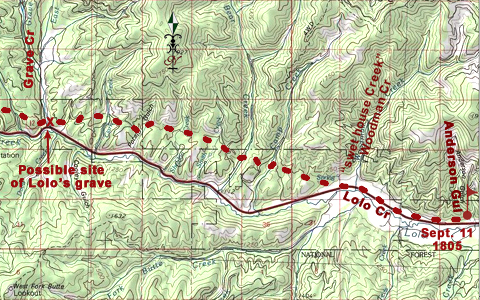

At 3 o’clock in the afternoon–the hottest hour of a very hot 11 September 1805–after the last two of the horses that had strayed the previous night were recaptured, Toby led the Corps of Discovery out of Travelers’ Rest camp toward the Bitterroot Mountain barrier. At the seven-mile mark on the wide, water-level road, they reached the mouth of today’s Anderson Gulch,[1]Mileages estimated when they were traveling on horseback were the most accurate of all, since horses will walk at an average of about 3½ miles per hour. where they made an early stop for the night near some old Indian lodges. Across the valley to the south loomed the two snow-mantled summits of Lolo Peaks.

Intolerable Road

Wakening on the twelfth to a crisp, frosty dawn, they continued westward for two miles, passing an earth-covered Indian sweat lodge. At that point the canyon floor narrowed down and became choked with underbrush, so the Corps “assended a high hill & proceeded through a hilley and thickly timbered Countrey for 9 miles” to a fork in the road at Grave Creek where they stopped for “dinner” (lunch). Travel conditions worsened by the hour. The road was “verry bad,” said Clark, “passing over hills & thro’ Steep hollows, over falling timber &c. &c.” They encountered “Some most intolerable road on the Sides of the Steep Stoney mountains.” Along the way Clark noted a number of ponderosa pines that been partly peeled for high-energy food (see Indigenous Forestry). At 8 P.M. Clark and some of the men descended “a long Steep mountain” to a camp site; for some unknown reason the rest didn’t get there until 10:00. The last terse statement he found the strength to write was “Party and horses much fatigued.”

The water-level road they followed as far as “swet house Creek” probably stayed closer to the foot of the mountains on the north side of today’s U.S. Highway 12 in order to stay out of the dense brush in the bottoms, and to get past the creek’s meanders that swung back and forth across the narrow valley floor. The first wagon road up the canyon was hacked and scraped out of the previously impassible canyon in 1888. Where it couldn’t squeeze past a meander, horses and wagons, and later automobiles, forded and re-forded the creek 29 times in 30 miles. Early in the 20th century, highway engineers simply shoved the creek out of the way. For example, in the center of the picture above notice the old creekbed north (right) of the highway, arching against the base of the mountain, and and then find the long straight stretch of relocated channel that hugs the south shoulder of the highway today.

Another Brush with Death

“Steep sides of the ridge”

To see labels, point to the picture.

© 2003 Airphoto, Jim Wark. All rights reserved.

The roads lacing the forest in this scene were built to get logging equipment and personnel into the forest and back, including trucks to haul the timber to mills. Many of the roads are closed permanently as soon as logging is done, while others are left open to accommodate hunters and other recreationists, and to facilitate access by forest firefighters. The Howard Creek road (not named after the expedition’s Thomas Howard) connects the Lolo Creek valley with the Clark Fork River valley.

Those mountainsides may not look very challenging from 1200 feet in the air, but they elicited a good many lamentations from the journalists on the westbound leg. Returning down this stretch on 30 June 1806, Lewis casually mentioned that after striking camp at the hot springs they “proceeded down the creek sometimes in the bottoms and at other times on the top or along the steep sides of the ridge to the N. of the Creek.” Before they got very far, though, he had added another memorable brush with death to his own “chapter of accidents.”

in descending the creek this morning on the steep side of a high hill my horse sliped with both his hinder feet out of the road and fell, I also fell off backwards and slid near 40 feet down the hill before i could stop myself such was the steepness of the declivity; the horse was near falling on me in the first instance but fortunately recovers and we both escaped unhirt.

Indeed, Lewis’s accident could have could have been tragic, considering not only the distance he fell and the steepness of the slope, but also the numerous fallen trees that cluttered the forest floor. Ponderosa pine, lodgepole pine, and Douglas-fir all prune themselves as they grow, cutting off nourishment to lower branches until they die and break off under the weight of snow or the urging of stormwinds, leaving short, sharp stubs or snags a few inches long protruding from the trunk. When the tree falls, from whatever cause, a certain percentage of those potentially lethal hazards are pointing upward, so the odds against accidentally impaling himself on one of them were not good. Indeed, on 18 July 1806 Private George Gibson, who was with Clark’s detachment on the Yellowstone River, “in attempting to mount his horse after Shooting a deer . . . fell . . . on a Snag and sent it nearly [two] inches into the Muskeler part of his thy. he informs me this Snag was about 1 inch in diamuter burnt at the end.” Gibson was laid up for several days, unable even to ride a horse for more than a couple of hours.

Lewis was lucky. He simply brushed himself off and went on with the business of exploring. In his very next breath he turned his attention toward the natural beauty around him. He took notice of the plant “which is sometimes called the lady’s slipper or mockerson flower.”

A Safe Return

On their return trip, having left behind “those tremendious mountanes,” as Clark called them, “in passing of which we have experiensed Cold and hunger of which I shall ever remember,” they “proceeded down the Creek, Sometimes in the bottoms and at other times on the tops or along the Steep Sides of the ridge to the N of the Creek.” With scarcely a nod toward their campsite of the previous 11 September 1806 they rolled on another eight miles at top speed. Shortly before sunset, with what was surely an overwhelming sense of relief and accomplishment, they sailed into their “old encampment on the S. Side of the Creek a little above its enterance into Clarks river.” There they settled down, Clark wrote, “with a view to remain 2 days in order to rest ourselves and horses and make our final arrangements for Seperation.”

Notes

| ↑1 | Mileages estimated when they were traveling on horseback were the most accurate of all, since horses will walk at an average of about 3½ miles per hour. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.