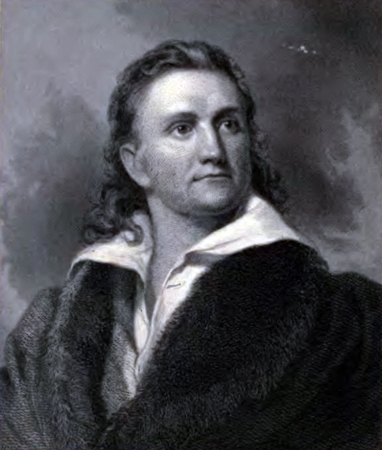

Although he never met Meriwether Lewis, America’s greatest ornithologist, John James Audubon, was just starting his career when Lewis and Clark returned, and there is ample evidence that he drew inspiration from Lewis and Clark’s writings. Born in 1785, Audubon was a generation younger than Alexander Wilson and the Jeffersonian naturalists of Philadelphia. These men however, particularly Wilson, motivated Audubon to amass his great collections. Audubon’s biographer, Richard Rhodes wrote that Audubon, “had Wilson’s volumes in hand and commented frequently and usually critically in the margins . . . indicating his renewed focus on surpassing his predecessor as he completed his collection . . . . improving on Wilson was Audubon’s primary justification for seeking to publish a new American ornithology.”[1]Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (New York, Knopf, 2004), 199.

In 1808, Audubon moved to Louisville, where he was introduced to the Clark family, and became an acquaintance of George Rogers, Jonathan, and William. Audubon got along well with this military family; his own father was a naval captain. There is little doubt that during his time in Louisville Audubon heard numerous stories of Western exploration from the Clarks.[2]Ibid., 53. As a frontier resident, it was difficult not to encounter someone who had a connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In 1811, Audubon met a number of the French engagés from the Expedition, including Toussaint Charbonneau, and wrote that he “was delighted to learn from them many particulars of their interesting journey.”[3]Ibid, 86.

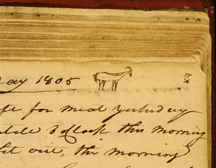

Although there is no direct evidence that Audubon ever read the Biddle/Allen narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, there is reason to believe that Audubon thought about, and even romanticized the Expedition. Over the next thirty years, while he collected and painted birds, the desire to retrace Lewis and Clark’s route lingered in his mind. Audubon unsuccessfully attempted to convince the government to fund his “Great Western Journey.” With age beginning to slow Audubon, he finally gathered corporate support for his plan from the Chouteau family in 1843. As a token to Audubon’s admiration of Lewis and Clark, D.D. Mitchell, the superintendent of Indian Affairs who approved Audubon’s plan to tour Indian country, reportedly presented him with one of William Clark‘s manuscript journals from 1805.[4]Ibid., 422. The source and eventual resting place of this journal is uncertain, but it is clear that the artist’s attempt to capture a portion Lewis and Clark’s West on canvas and in text was an important motivator for one of America’s leading naturalists.

Quadrupeds of North America

Between 1839 and 1852, already famous for his beautiful paintings in The Birds of America (4 vols., 1827–38), John James Audubon (1785–1851), aided by his sons John Woodhouse and Victor, and the naturalist John Bachman,[5]Bachman, an ordained minister who continued his demanding pastoral duties while writing for the Audubons without pay, also founded the Lutheran Synod of South Carolina, and the state’s Lutheran … Continue reading published the 3-volume Quadrupeds of North America. It included 150 plates lithographed by the talented William Hitchcock and hand-colored by J. T. Bowen under the artists’ supervision.

While Meriwether Lewis was shopping and studying in Philadelphia, in 1803, the young French ex-patriot Audubon, destined to make an indelible mark on the cultural face of America, was beginning to get acquainted with his adopted homeland, beginning as a businessman. Self-taught as a naturalist and artist, in 1820 he began his monumental Birds of North America, four “elephant folio” volumes containing 435 color plates that captured his subjects with an energetic, elastic grace. In 1843, he set out to create a second, equally monumental opus, Quadrupeds of North America, which was completed five years later. One-third of its 150 hand-colored lithographs were painted by one of his sons, John Woodhouse, with backgrounds by the latter’s younger brother, Victor.

Engravings v. Lithographs

In the old process of engraving, lines were gouged into a soft copper plate with sharp instruments. The plate was washed with ink and then wiped dry, leaving ink only in the grooves. When a sheet of paper was pressed against the engraved plate, the image was transferred to it. Lithography, however, used a smooth, flat, porous limestone—about 3″–4″ thick, imported from Bavaria—upon which a design was drawn with a greasy crayon or ink made from wax, lampblack, oil, and soap. The stone was drenched with water, which soaked in everywhere that was not covered by the crayoned image. An oily ink, applied with a roller, adhered to the drawing but not to the wet parts of the stone. When a sheet of paper was pressed against the stone, it received the inked image.

The process of lithography had been invented in 1798, but was not widely employed by the printing industry until after 1820, and another fifty years or so elapsed before the full potential of color lithography was reached—about the time when photographic processes evolved that would eventually replace it. In Audubon’s day, color still had to be applied by hand, as in the old days of engraving. Neither engraving nor lithography have been used by the printing industry since the early 20th century, although they have remained highly valuable as artistic media.

Colorizing

Common Virginian Deer

Drawn from Nature by J. W. Audubon

Courtesy Special Collections and Archives. University of Idaho Library. SPEC QL715A9 1849.

On Stone by Wm. E. Hitchcock Lithograph Printed & Colored by J. T. Bowen, Philadelphia. Original size, 8 x 4 in.

In this striking depiction the artist, whose father had passed on his own knowledge of quadrupeds’ anatomy to his son, has here presented his subjects from the inside out, showing their musculature with intense super-realism.

Colors of flora and fauna are the most difficult qualities to capture with paint because their shades and hues depend so much upon the transitory effects of season, time of day, quality of light and shadow, and various other factors. As Bachman reminded John James, “color is as variable as the wind.”[6]Letter, 13 January 1840. Quoted in Alice Ford, John James Audubon (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), 368. It was for that reason, primarily, that many 18th-century naturalists preferred plain black and white engravings.[7]To circumvent the uncertainties of paint, elaborate vocabularies were developed, by which colors could be specified, such as Werner’s nomenclature of colours, . . . arranged so as to render it … Continue reading J. J. and J. W. Audubon together carried wildlife illustration a giant step forward. The Audubons presented their subjects in more dynamic attitudes than the others, even in states of repose such as that of the fawn shown above. “In his finest paintings of quadrupeds,” wrote Constance Rourke, “every tiny hair seems spun to tension by cold wind, or by fear, or by the lust for prey, and the small squirrels and prairie dogs and gray rats are shown in fleeting subtle movement.”[8]Constance Rourke, Audubon (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 302. Above all, the subtle nuances of color—”The brush of my old friend, Audubon,” Bachman wrote to Victor, “is a truth-teller.”[9]Letter, November 1844, quoted in Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time, 2 vols (New York: Appleton and Company, 1917), 262.M.—made those reverent, often vibrant, paintings of quadrupeds immediately and widely popular. The first edition of Quadrupeds numbered 303 copies; nearly 50 reprints were published up to the end of the 20th century.

With the passage of time the original hues of J. W. Audubon’s conceptions may have faded somewhat, and the paper it was printed on may now be a different shade. Moreover, the unpredictable effects of digital media—especially the virtually incalculable differences in calibration among computer monitors—might mean that what we are seeing on this page today is more or less remote from the artist’s intent. On the other hand, just by chance, it might be exactly right.

Featured Artwork

Lewis got his first close look at that “large hare of America,” when one of the Corps’ ace hunters, Private John Shields, bagged the first specimen more than 1,100 miles (by Clark’s estimate) up the Missouri River.

Daniel Boone was sixty-nine years old in 1803, too old to go traipsing out to the Pacific Ocean. But Lewis’s “qualifycations” suggest that Boone would have been precisely the kind of hunter he hoped to find.

Bighorn Sheep Encounters

by Joseph A. Mussulman

During a reconnaissance assignment eight miles up the Yellowstone River on 26 April 1805, Joseph Field became the first member of the Corps to glimpse a live bighorn sheep.

The species remained nameless until John James Audubon dubbed it neglecta because, he wrote in 1840, although “the existence of this species was known to the celebrated explorers of the west, Lewis and Clark . . . no one has since taken the least notice of it.”

Classifying Bighorn Sheep

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The first naturalist to publish an honest admission of uncertainty over the respective identities of the wild sheep and goat of North America was John Davidson Godman (1794-1830). Audubon and Bachman contributed illustrations and descriptions.

Lewis’s conviction that the “black tailed fallow deer of the coast” and the “common fallow deer” were two distinct species was sufficient to urge later investigators to try to clarify them.

One of the most confusing terms in Lewis and Clark’s lexicon of quadrupeds was the adjective long-tailed—or longtailed. At the Three Forks on 29 July 1805, he compounded the ambiguity.

In 1798 a German actor-playwright-turned-printer named Alois Senefelder (1771-1834) discovered the principle of lithography, relying upon simple chemical principles—the mutual repulsion of oil and water, and the mutual attraction of water and salt.

Lewis had no reason to write about the common or fallow deer of the East Coast, although in using it for the purpose of comparison, he gave quite a clear picture of it. John Godman’s 1828 description relied partly on Lewis and Clark’s journals.

Drouillard spotted the first “Deer with black tales” on 5 September 1804, on the cliffs upstream from the mouth of the Niobrara River in northeast Nebraska. By 10 May 1805 Lewis had seen enough specimens to write an 800-word description of the new species.

Notes

| ↑1 | Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (New York, Knopf, 2004), 199. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid., 53. |

| ↑3 | Ibid, 86. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., 422. |

| ↑5 | Bachman, an ordained minister who continued his demanding pastoral duties while writing for the Audubons without pay, also founded the Lutheran Synod of South Carolina, and the state’s Lutheran theological seminary. |

| ↑6 | Letter, 13 January 1840. Quoted in Alice Ford, John James Audubon (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964), 368. |

| ↑7 | To circumvent the uncertainties of paint, elaborate vocabularies were developed, by which colors could be specified, such as Werner’s nomenclature of colours, . . . arranged so as to render it highly useful to the arts and sciences, by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817), published in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1814. Note that in the prospectus for Lewis’s proposed volume on his discoveries in natural history, nothing was written to indicate whether the illustrations would be in color or not. |

| ↑8 | Constance Rourke, Audubon (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1936), 302. |

| ↑9 | Letter, November 1844, quoted in Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist: A History of His Life and Time, 2 vols (New York: Appleton and Company, 1917), 262.M. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.