Menzies, Lambert and Poiret

The nomenclatural morass associated with the scientific name of Douglas-fir, Pseudotsuga menziesii, is a long and complex tale. The history of its scientific name is tied closely with the history of early explorations along the western coast of North America, and the development of our modern system of rules for the naming of plants embodied in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature. The present-day name, Pseudotsuga menziesii, is only the latest innovation in a long series of learned pronouncements, and for the uninformed, the relationship of the scientific name to its common name, Douglas-fir, is hardly obvious.

The tree was seen by various naturalists who visited the Pacific Northwest in the later part of the eighteenth century, usually from aboard ship looking onshore. It was the surgeon-naturalist Archibald Menzies aboard HMS Discovery—captained by George Vancouver—who first collected specimens. Apparently, he gathered them in July 1792 (not 1791 as often reported) from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada. They probably were sent to England in the fall of that year, but it is not known when Sir Joseph Banks, Menzies’ sponsor before the Admiralty, received the specimens. If seeds were gathered in 1792, or in 1794 when Menzies returned to the Island, there is no evidence they reached England or, if so, that the tree was introduced into cultivation.

In September 1803, the English conifer expert, Aylmer Bourke Lambert, assigned the name Pinus taxifolia (tax-eh-FOHL-ee-ah, having needles like the yew tree, a member of the genus Taxus [TAX-us]) to Menzies’ specimens in his now rare book A description of the genus Pinus. Unfortunately this name was a homonym, that is, the same name (Pinus taxifolia) had been used for a totally unrelated conifer by another English naturalist, Richard Salisbury, in 1796. Two years later the French clergyman and botanist Jean Louis Marie Poiret, writing various portions of the botany section for Jean Baptiste Lamarck’s Encyclopédie Méthodique, inadvertently proposed the new name Abies taxifolia in August 1805. Remarkably, once again this name was a later homonym.

According to our modern rules of botanical nomenclature, a later homonym is considered to be an illegitimate name, and, being a name proposed in opposition to the rules, it cannot be used. Although the tree was described and known to the scientific world, it did not yet have a correct (“valid” in the jargon of the rules) name.

Lewis, Clark and Pursh

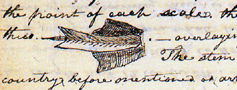

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were the next to observe the plant, Lewis describing it in detail on two occasions, and probably collecting specimens. He described the tree now called Douglas-fir while at Fort Clatsop on February 5, 1806, designating it “Fir No. 5.” On February 9 he added some details and drew a figure in his journal of the distinctive bract of the cone. On their return trip across the northern Rocky Mountains of Idaho and Montana, the captains repeatedly encountered the inland expression of the species, the Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir. It is possible that Lewis collected specimens of this tree also.

The Saxon botanist Frederick Pursh, who described many of the new Lewis and Clark species in 1813, associated Lewis’s plant collection with Lambert’s Pinus taxifolia, noting that he had two expressions. He wrote:

This elegant and tall tree has some resemblance to the following one [Pinus canadensis (can-a-DEN-sis—from Canada), now Tsuga canadensis (TSOO-gah), eastern hemlock], but the leaves are more than twice the length. I have among my specimens two varieties, or probably distinct species, which for want of fructification [cones] I cannot decide: one has acute leaves, green on both sides; the other emarginate leaves, glaucous underneath.

The “specimens” Pursh alluded to were those gathered on Vancouver Island by Menzies and whatever Lewis obtained supposedly “On the banks of the Columbia.” Unfortunately, Lewis’s specimens are lost, or at least not yet relocated. Given Pursh’s remarks about the nature of the specimens he had at hand, it is possible the Lewis collection was the inland form with blue-green (or glaucous) needles, Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca (GLAW-ka, referring to the blue-green condition of the needles) or the Rocky Mountain Douglas-fir. This variant of Douglas-fir is common in Idaho and Montana. The coastal phase, or Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii, only has dark yellow-green needles, and this was certainly the element Menzies found on Vancouver Island. Equally possible, of course, is that Lewis gathered Douglas-fir twice, once along the lower Columbia River (var. menziesii—his “No. 5”) and again in the Rocky Mountains (var. glauca).

Rafinesque and Douglas

In 1832, the eccentric naturalist Constantin Samuel Rafinesque-Schmaltz, described six new species of Abies from Oregon. Rafinesque had no specimens, apparently, basing his description entirely upon Lewis’s descriptions. Among the six was Abies mucronata (mew-CROW-na-tah, alluding to the pointed bracts of the cone found in the two species of Pseudotsuga). He wrote:

5. Abies mucronata R. (Fifth Fir L. C.) bark scaly, branches virgate, leaves scattered very narrow, rigid, and oblique, sulcate above, pale beneath. Cones ovate acute, scales rounded nervose mucronate. Rises 150 feet, leaves sub-balsamic, one inch long, 1-20th wide, cones very large two and a half inches long. Var. palustris. Grows in swamps, only 30 feet high and with spreading branches.

The description of Abies mucronata was based on Lewis’s description of Douglas-fir written on February 6, 1806, whereas the description of Rafinesque’s Abies mucronata var. palustris (pal-US-tress, of a swampy place) was taken from Lewis’s notes made on February 9. Interestingly, Rafinesque recognized Abies mucronata as a new species as early as 1817 in his manuscript “Florula Oregonensis,” a work he never published. Had he done so, the scientific names of Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis [sit-CHEN-sis, from Sitka]), grand fir (Abies grandis [GRAN-dis, large, as to the size of the tree), Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis [a-MAB-ill-iss, lovely]), and Douglas-fir would all be different. Of the six species proposed by Rafinesque, only one, the western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla, called Abies heterophylla [heter-oh-PHIL-lah, alluding to the different sizes of needles on the same branch as reported by Lewis] by Rafinesque) remains in use today. That was based on Lewis’ fir “No. 2.”

When the plant was collected again, it was by the Scottish botanist David Douglas, who gathered seeds and specimens of the tree along the Columbia River in 1825 and again in 1830 for the Royal Horticultural Society. Based on the notes in his early Journal, published in 1914, Douglas gathered dried specimens in April (his number 82bis, bis meaning “again”; he assigned two different plant collections the same number). He does not report obtaining seeds in 1825, lamenting in September while along the Columbia River the “cones being on the top, I was unable to procure any.” However, by 1830 he had seeds aplenty to send to England and the tree was soon in cultivation.

Don, Sabine, and Others

In 1832, the plants Douglas collected were named Pinus douglasii (doug-GLASS-ee-eye, after David Douglas) by David Don, an English botanist and librarian for both Lambert and the Linnean Society. Don proposed a name suggested by Joseph Sabine, the secretary of the Horticultural Society. A year later, John Lindley renamed the plant Abies douglasii in the Penny Cyclopaedia, a weekly publication of a few pages of a multi-volume encyclopedia costing only a single English penny per issue. It was with this publication that the common name “Douglas-fir” had its origin, replacing the then frequently used “Oregon pine.” Unlike most common names, Douglas-fir would remain consistently applied to the species, while its scientific name, as we shall see, would undergo several changes.

It was not until 1867 that the genus Pseudotsuga was proposed. In his second edition of Traité général des conifères, the French horticulturist Elie-Abel Carrière established Pseudotsuga douglasii, basing his name on Pinus douglasii. This name would remain in use until Nathaniel Lord Britton, the founder of the New York Botanical Garden, proposed Pseudotsuga taxifolia in 1889. Britton suggested, incorrectly according to our modern rules of botanical nomenclature, that Pinus taxifolia (1803) was the first correct name for the tree, inasmuch as Pinus douglasii was proposed in 1832. What Britton failed to note was that Pinus taxifolia, proposed in 1803, was a later homonym, since the very same name was published in 1796. In short, the 1803 species epithet “taxifolia” was not available for Britton to use.

In the documentation of scientific nomenclature, every day counts. It is not known exactly when, in 1832, Don published the third edition of Lambert’s A description of the genus Pinus. Rafinesque’s Atlantic Journal, wherein he proposed Abies mucronata, was published sometime during September or October of 1832. In 1897, the American forester George Sudworth proposed Pseudotsuga mucronata suggesting that Abies mucronata predated Pinus douglasii. Sudworth abandoned this name the following year and took up Pseudotsuga taxifolia in a slightly modified form. Even so, Charles Sprague Sargent who published a new American silva maintained Pseudotsuga mucronata was the correct name in 1898, and considered Britton’s Pseudotsuga taxifolia to be incorrect.

Sprague, Green, Little, and Franco

By 1895 it was well known that Lambert’s Pinus taxifolia was a later homonym. However, if one considered Poiret’s Abies taxifolia to be a new name for Pinus taxifolia, as Sudworth suggested, then the epithet “taxifolia” becomes available for use in Pseudotsuga. Sudworth then proposed Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw. in 1897. Unfortunately, at this time it was not known that even Poiret’s Abies taxifolia was a later homonym!

The stage was then set for a series of esoteric arguments over the correct name for Douglas-fir. During the period from 1897 until 1938, three different scientific names were used for one of the most important forest trees in all of North America: Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Lamb.) Britt. or more correctly Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw., Pseudotsuga douglasii (Sabine ex D. Don) Carr., and Pseudotsuga mucronata (Raf.) Sudw.[1]It is traditional in botanical nomenclature for the individual, or individuals, who name a plant to have their name associated with that plant’s name. Often, the person’s name is … Continue reading

In 1938, two English taxonomists skilled in botanical nomenclature, Thomas A. Sprague and Mary L. Green, concluded that the correct name was Pseudotsuga taxifolia, based not on the illegitimate Pinus taxifolia Lamb. (1803) but on Abies taxifolia Poit. (1805). They proposed Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poit.) Rehder ex Sprague & Greene. Six years later the American forester and taxonomist Elbert Little, writing in the American Journal of Botany, noted that Sudworth proposed this same name 41 years earlier and concluded that the correct citation should be Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw. For a brief period of time, this was widely accepted, and the scientific name of Douglas-fir seemed to be finally settled.

In 1950, Joäo Manuel Antonio do Amaral Franco (born in 1921), a Portuguese botanist, once again published on the nomenclatural history of the scientific name of what by then was consistently known as Douglas-fir. Franco discovered two important facts. The first was that Abies taxifolia Poir. was itself a later homonyn and thus Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw., then in common use, could not be the correct name for the tree. The second and most important discovery was a previously unnoticed name in the French journal, Mémoires du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle.

Mirbel and Desfontaines

In 1825, the famed French plant anatomist, physiologist and taxonomist, Charles Mirbel, proposed Abies menziesii (as “Menziezii”) as a new name for the nomenclaturally incorrect Abies taxifolia. Amazingly, Mirbel’s name had gone unnoticed for 125 years. Writing in an obscure Spanish journal, Franco proposed Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco for the green-leaved coastal phase and Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco var. glauca (Beiss.) Franco, for the glaucous-leaved expression common to the Rocky Mountains.

This conclusion was soon challenged by Little. Writing in Leaflets of Western Botany in 1952, Little once again maintained the correct scientific name for Douglas-fir was Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw. He acknowledged that the French botanist René Louiche Desfontaines validly published Abies taxifolia in 1804, but Little assumed Poiret’s name was also published in 1804 and therefore considered Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw. to still be the correct name. Soon after he published, Little learned that the section of Lamarck’s Encyclopédie Méthodique was actually published on August 28, 1805, and thus Abies taxifolia Poit. was a later homonym and the name Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw. was not correct.

Formal adoption of Pseudotsuga menzesii (Mirb.) Franco for the giant forest tree known as Douglas-fir began in 1953 when Little accepted the name in his Check list of native and naturalized trees of the United States (including Alaska). The name has remained unchallenged since then.

The fates were destined to combine the English surgeon-naturalist Archibald Menzies with the Scottish botanical collector David Douglas into the naming of one of North America’s most important forest trees, with the discoveries of Meriwether Lewis merely footnotes. And the fates were to perpetuate a common binomial that is incorrect on both sides: This tree is not Douglas’s, and it is not a fir. At best, the name memorializes a famous early Scottish-American botanist, and one entirely forgivable error in identification by Meriwether Lewis.

There is no question that Lewis described the coastal expression now known as var. menziesii, and he also saw the inland expression var. glauca in Idaho and Montana. But what happened to Lewis’s specimens of Pseudotsuga menzesii (Mirb.) Franco? Pursh certainly saw them. But did he take them with him to England, or did he leave them in Philadelphia? Perhaps they will eventually be found, and this long and complicated tale will come to an end.

Summary

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco—Douglas-fir

Pinus taxifolia Lamb., Descr. Genus Pinus 1:53, pl. 33. 1803, non P. taxifolia Salisb. (Prodr.: 399. 1796). Abies taxifolia Poir. in Lam., Encycl. Méth. Bot. 6:523. 1805, non A. taxifolia Desf. (Tabl. Ecole Bot.: 206. 1804). Abies menziesii Mirb., Mém. Mus. Hist. Nat. 13: 63, 70. 1825. Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Lamb.) Britt., Trans. New York Acad. Sci. 8: 74. 1889. Pseudotsuga taxifolia (Poir.) Britt. ex Sudw., U.S.D.A. Div. Forestry Bull. 14: 46. 1897. Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco, Bol. Soc. Brot., ser. 2, 24: 74. 1950. (Menzies s.n., Vancouver Isl., 1791; specimen at The Natural History Museum, London).

Pinus douglasii Sabine ex D. Don in Lamb., Descr. Genus Pinus, ed. 3, 2: unnumbered page between 144 and 145. 1832. Abies douglasii (Sabine ex D. Don) Lindl., Penny Cyclop. 1: 32. 1833. Pseudotsuga douglasii (Sabine ex D. Don) Carr, Trait. Conif., ed. 2: 256. 1867. (Douglas s.n., Willamette River, Oregon, Oct 1830; specimen at the Royal Botanic Garden, Kew England).

Abies mucronata Raf., Atl. J. 1: 120. 1832. Pseudotsuga mucronata (Raf.) Sudw. in Holz, Contr. U.S. Nat. Herb. 3: 266. 1895. (Lewis 5, near the mouth of the Columbia River, Clatsop Co., Oregon, 6 Feb 1806; described from Lewis’ notes – specimen unknown).

For illustrations of Douglas-fir see the first volume of “Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest” by Hitchcock and his associates, and the second volume of Flora of North America north of Mexico.

References

Boewe, C. 1982. Rafinesque: A sketch of his life with bibliography by T. J. Fitzpatrick, revised by Charles Boewe. M & S Press, Weston, Massachusetts.

Carriére, E. A. 1867. Traité général des coniféres. Ed. 2. Published by the author, Paris.

Coats, A. M. 1970. The plant hunters: Being a history of the horticultural pioneers, their quests and their discoveries from the Renaissance to the twentieth century. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Douglas, D. 1914. Journal kept by David Douglas during his travels in North America, 1823-1827. Royal Horticultural Society, London.

Ewan, J. 1952. “Frederick Pursh, 1774-1820, and his botanical associates.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 96: 599-628.

Ewan, J. 1979. “Introduction to the facsimile reprint of Frederick Pursh’ Flora americae septentrionalis (1814),” p. 7-117. In: F.T. Pursh, Flora americae septentrionalis. Facsimile reprint. J. Cramer, Vaduz.

Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). 1993. Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 2. Oxford University Press, New York.

Franco, J. A. F. 1950. Cedrus libanensis et Pseudotsuga menziesii. Boletim da Sociedade Broteriana, sér. 2, 24: 73-76.

Gascoigne, J. 1998. Science in the service of Empire: Joseph Banks, the British State and the uses of science in the age of revolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Goetzmann, W. J. 1966. Exploration and empire. W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., New York.

Hitchcock, C. L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey & J. W. Thompson. 1969. “Vascular plants of the Pacific Northwest.” University of Washington Publication of Biology 17(1).

Hooker, W. J. 1836-1837. “A brief memoir of the life of Mr. David Douglas, with extracts from his letters.” Companion to the Botanical Magazine 2: 79-182 [in four parts].

Isley, D. 1994. One hundred and one botanists. Iowa State University Press, Ames.

Kastner, J. 1977. A species of eternity. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Little, E. L. 1941. “Notes on nomenclature in Pinaceae.” American Journal of Botany 31: 587-596.

Little, E. L. 1952. “The genus Pseudotsuga (Douglas-fir) in North America.” Leaflets of Western Botany 6: 181-198.

Little, E. L. 1953. “Check list of native and naturalized trees of the United States” (including Alaska). United States Department of Agriculture Handbook 41.

Little, E. L. 1979. “Checklist of United States trees (native and naturalized).” United States Department of Agriculture Handbook 541.

Lyte, C. 1980. Sir Joseph Banks. David & Charles, London.

Mirbel, F. B. 1825. “Essai sur la distribution gèographique des conifères.” Mèmorie du Musèum d’Histoire Naturelle 13: 28-76.

Morwood, W. 1973. Traveler in a vanished landscape. The life & times of David Douglas, botanical explorer. Clarkson N. Potter Inc., Publisher. New York.

Moulton, G. E. (ed.). 1990. The journals of the Lewis & Clark expedition. The herbarium of the Lewis and Clark expedition. Volume 6. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Pursh, F. T. 1813. Flora americae septentrionalis. 2 vols. White, Cochrane, and Co., London.

Rafinesque, C. S. 1832. “Six new firs of Oregon.” Atlantic Journal 1: 119-120.

Reveal, J.L. 1968. “On the names in Fraser’s 1813 catalogue.” Rhodora 70: 25-54.

Reveal, J. L. 1992. Gentle conquest. The botanical discovery of North America with illustrations from the Library of Congress. Starwood Publishing, Washington, D.C.

Reveal, J. L. & J. S. Pringle. 1993. “Taxonomic botany and floristics,” pp. 157-192. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.), Flora of North America north of Mexico. Volume 1. Oxford University Press, New York. See http://www.inform.umd.edu/PBIO/usda/fnach7.html for an online version.

Sargent, C. S. 1890-1902. The North American sylva. 14 vols. D. Appleton & Co., New York.

Spongberg, S. A. 1990. A reunion of trees. The discovery of exotic plants and their introduction into North American and European landscapes. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

Stearn, W. T. 1981. The Natural History Museum at South Kensington. A history of the British Museum (Natural History), 1753-1980. Heinemann, London.

Sterling, K. B. 1978. Rafinesque, autobiography and lives. Arno Press, New York.

Sudworth, G. B. 1897. Nomenclature of the arborescent flora of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Sudworth, G. B. 1898. Check list of the forest trees of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Sudworth, G. B. 1927. Check list of the forest trees of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Notes

| ↑1 | It is traditional in botanical nomenclature for the individual, or individuals, who name a plant to have their name associated with that plant’s name. Often, the person’s name is abbreviated. Scientific names come in two parts, the first of which is also in two parts. The binomial is a combination of a generic name and a specific epithet. Pseudotsuga is a generic name. The epithet modifies the generic name, identifying the species, variety, or other division of the genus. In the case of Douglas-fir, the correct epithet is menziesii. All binomials are in Latin or composed of words treated as if they were Latin; binomials are always in italics with the generic name capitalized and, by modern tradition, the specific epithet in lower case. The second part of a scientific name is its authorship. White oak, for example, was named by Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) in 1753, the Swedish naturalist who began our modern system of nomenclature. The scientific name of white oak is Quercus alba L., the “L.” being an abbreviation for Linnaeus. One can think of such a name as the “white oak named by Linnaeus.” In the case of Douglas-fir, the authorship portion is more complex. Mirbel’s name, abbreviated “Mirb.” is placed in parenthesis. This informs the botanist that Mirbel proposed the specific epithet menziesii but placed it a genus other than Pseudotsuga—specifically, he associated the epithet with the generic name Abies. The name of the second person, Franco, is not abbreviated because it is relatively short. Franco’s name follows Mirbel’s but is outside the parenthesis. This informs the botanist that Franco transferred the epithet menziesii from Abies to Pseudotsuga. Occasionally the word “e”X—Latin for “from”—may be found between two authors’ names, as in “Sabine ex D. Don.” This is a special condition in which a botanist attempts to record the history of a name in its authorship. As noted already, it was Sabine who suggest that Don name the then Oregon pine for David Douglas, but it was Don who actually published the name. Thus Sabine suggested “douglasii” but Don put the name into print. |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.