Calm tho’ not mean, courageous without rage,

Serious not dull, and without thinking sage;

Pleased at the lot that nature has assign’d,

Snarl as I list, and freely bark my mind,

As churchman wrangle not with jarring spite,

Nor statesman-like caressing whom I bite;

View all the canine kind with equal eyes,

I dread no mastiff, and no cur despise.

True from the first, and faithful to the end,

I balk no mistress, and forsake no friend.

My days and nights one equal tenor keep,

Fast but to eat, and only wake to sleep.

Thus stealing along life I live incog,

A very plain and downright honest dog.

Few of the journalists’ written words could have had quite as much force and clarity with their readers in 1814, as their occasional evocations of one or more of the five senses, each “a faculty of the soul.” Furthermore, in an age when there were no universal standards of measurement for area, volume, nor linear dimensions, comparison was a natural mode of expression. It was imprecise, but it was sufficient for general pre-scientific purposes.[1]The metric system was introduced in France in 1799, and is now employed throughout nearly every country in the world except the United States. Finally, there is no practical, universal standard, other than comparison, that can as effectively serve for the description or identification of sounds. Indeed, the sonic dimensions of the expedition have yet to be fully measured, and it may as well begin with a particular dog’s bark, or “note.”[2]In his first dictionary (1806), Noah Webster defined “note” as, for one thing, “a mark,” or “token.” Later, in his American Dictionary of the English Language … Continue reading

Meriwether Lewis seems to have been a natural dog lover from an early age. Thomas Jefferson recalled in his biography of Lewis that, “when only eight years of age he habitually went out in the dead of the night, alone with his dogs, into the forest to hunt the raccoon and opossum, which, seeking their food in the night, can then only be taken.”[3]Jefferson’s preface to Nicholas Biddle‘s History of the Expedition (1814), p. ix. The Corps’ journalists, in their accounts of new species of mammals they encountered on the expedition, would occasionally call to mind comparable features of domestic canids whenever it was appropriate—in terms of their sizes, morphology, and “notes” or barks—in order to clarify their descriptions. Those references helped to clarify the physical aspects of a few unfamiliar wild animals, or add to the sonic dimensions of the expedition’s environments.

Turnspit Dog

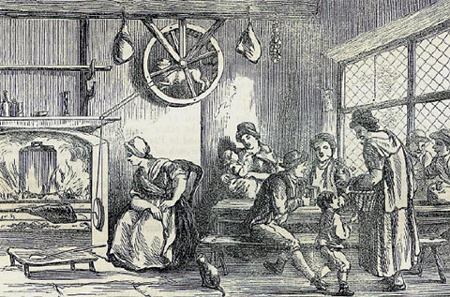

Figure 1

An 18th Century Automated Roasting Spit

Henry Wigstead, Remarks on a Tour to North and South Wales in the Year 1797.

At top-center a turnspit dog, or simply a “turnspit,” trots in a treadwheel that is connected to the spit at lower left by three pulleys. One is on the treadwheel’s axle, the second is attached to the mantle above the hearth to rotate the axis 90 degrees, and the largest pulley is mounted on the axle of the spit to reduce the speed of the treadwheel down to the optimum velocity for slow, even roasting.

The chief cook, or one of her helpers, was responsible for monitoring the roast and keeping the dog on task. The cook in a large household might have required at least two turnspit dogs of equal strength and endurance to spell one another. In the illustration above, she is seated close beside the hearth so as to be shielded from the direct heat of the fire and within easy reach of the treadwheel in case the dog needs discipline or encouragement. The proximity of what appears to be a haunch of ham hanging nearest to the treadwheel might have helped with the latter.

The drip pan is on the floor at her feet, and she has two spoons for basting, one in her hand, the other in the pan. The kitchen cat sits poised at her feet, eager to help clean up any spills and dispatch any uninvited mice bold enough to intrude. As usual—then as today—the kitchen was a favored domestic gathering place. Not only was it warm, but its aromas were invigorating.

The kitchen scene above originally was printed from an engraved sheet of copper, but all of the following pictures of dogs that appeared in the fourth edition (1800) of A General History of Quadrupeds were printed from engravings made by the English illustrator Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) in fine-grained basswood.[4]Bewick and Beilby collaborated on the highly successful study, A General History of Quadrupeds, the Figures Engraved on Wood, 4th ed. (Newastle Upon Tyne: S. Hodgson, R. Beilby, and T. Bewick, 1800), … Continue reading

On 26 February 1806 at Fort Clatsop, for example, Lewis summarized all he had learned about the badger, or Braro, as their French-Canadian hired hands had called it. The body, he observed, was rather long in proportion to its thickness, and “the forelegs [are] remarkably large and muscular and are formed like the ternspit [turnspit] dog” (Fig. 1).

Lewis thought of a typical turnspit dog as having forelegs bent —elbows outward, wrists inward —like those of the badger. In dogdom that conformation is a genetic anomaly known as achondroplasic dwarfism. It occurs in the dog’s legs, which are short for the body’s length, and in its head and face, which are foreshortened like those of a pug-dog. In fact, a turnspit’s short legs could be either crooked or straight, depending on its bloodline. Either attribute would be acceptable for this job, since both would center the dog’s weight close to the outer radius of the wheel, and result in more efficient transfer of the dog’s energy through the turnspit mechanism. A short muzzle, if not the stubby nose of a pug-dog, would prevent the working animal from bumping that most sensitive part of his anatomy. It all added up to a simple exercise in plane geometry. There was some disagreement also as to which side of the body a turnspit’s tail should curl toward (compare Figures 2 and 3), but the consensus was that it should curl over the dog’s right hindquarters.

Bewick described the turnspit as “a bold, vigilant, and spirited little Dog.” He and his collaborator, an English engraver on steel and silver named Ralph Beilby (1744-1817), maintained that the typical turnspit dog had a blue-grey coat with black spots. William Bingley (1774-1823) said it was usually all black except for the white streak over the head.[5]The Rev. William Bingley (1774-1823) published his Animal Biography in 1802, aiming to offset a tendency among the faithful to regard the new popular science of “natural history” as … Continue reading Georges Buffon said that a turnspit dog was “generally a dusky grey, spotted with black; or entirely black, with the under parts whitish.”[6]Georges-Louis Leclerc, count de Buffon, Histoire naturelle, genérale et particuliére, Vol. 5 (Paris: de L’Imprimérie, 1755), 123. Internet Archive.

Bewick insisted, moreover, that a good turnspit dog was often identifiable by its eyes, the iris of one being black, the other white. But that condition, called heterochromia iridis (varicolored irises) is but another genetic anomaly, and may simply have been a coincidental feature of a few conspicuously talented turnspit dogs. By 1829, turnspit dogs were of merely historical interest, but the British naturalist Captain Thomas Brown, perhaps prompted by illustrations such as those of Bewick, Beilby and Bingley, in retrospect felt obliged to clarify one point: The shape of a turnspit’s head was “something between that of the pointer and hound, with long ears.”[7]Captain Thomas Brown, Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1829), 418.

By the end of the 18th century, Bewick noted, turnspit dogs in England were being replaced by more certain methods of covering the business of the spit, such as Benjamin Franklin’s “Pennsylvania Fireplace” of 1740, which basically eliminated the hazards, inefficiencies and inconveniences of the open hearth for cooking.

In general the word turnspit referred to any dog possessing the physical characteristics and temperamental proclivities to do that particular job, and did not identify a particular breed. Carl Linnæus (1707-1778) however, in his Systema naturæ of 1758, defined the turnspit dog as a unique species, giving it the trinomial Canis familiaris vertagu, which translates as “common tumbler dog.” Linnæus may have called it a “tumbler dog” on the mistaken impression that the turnspit would have been “tumbled” about in the treadwheel. However, that name had at least one other long-standing connotation in the British Isles, where tumbler dogs—also known as lurchers—were particularly adept at hunting rabbits because, according to John Caius, “they turne and tumble, winding their bodyes about in circle wise, . . . so that the simple Conny [coney, rabbit] is debarred quite from his hole.” Neither the tumbler nor the lurcher were mentioned in the journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition.[8]John Caius, De Canibus Britannicis (London: Gulielmum Seresium, 1570). Translated by William Fleming as Of Englishe Dogges, 1576, reprinted 1729.

Feist Dog

Meriwether Lewis embellished his comparison of the badger and the turnspit with his judgment that the badger’s head was formed “much like the common fist [feist; rhymes with “iced”] dog only that the skull is more convex.” William Clark used feist once too. He noted that at about 5 o’clock in the evening of 12 August 1804, he and Captain Lewis went on shore “to Shoot a Prarie wolf”—coyote, that is—that barked at them as they passed on the river. It “barked like a large fest [feist],” he noticed, “and is not much larger.”

Noah Webster didn’t include “feist” in either his first (1806) or second (1828) dictionaries, nor is it found in any of the books on dogs that we have consulted so far for this article, most of which were written by British authors and published there.

However, the Dictionary of American Regional English lets us in on the story of the type: “a small bad-tempered dog.” No feist-lover would agree with that, but that is after all where we got the adverb feisty. Feists are bred not for show, but for hunting, so there exists much variety in their appearance. In general, they are under 18 inches with short hair and long legs. They are adept at chasing and treeing prey and typically do not bark during the chase.[9]http://www.ireference.ca accessed on 15 November 2010.

Cur-dogs

Lewis summoned the image of the “common cur” in order to convey some sense of the look of “the Indian dog.” It was, he reported on 16 February 1806, “usually small or much more so than the common cur.” Moreover, the Indian dog’s hair was “short and smooth except on the tail where it is as long as that of the curdog and streight.”

Captain Lewis wrote of them on 16 February, at Fort Clatsop:

The Indian Dog is usually small or much more so than the common cur. they are party [parti-]coloured; black white brown and brindle are the more usual colours.[10]Brindle has commonly been used since the late 17th century in describing cattle and, especially, dogs. The American Heritage Dictionary defines it as “tawny or grayish with streaks or spots of … Continue reading the head is long and nose pointed eyes Small, ears erect and pointed like those of the wolf, hair Short and Smooth except on the tail where it is as long as that of the Cur dog and streight. the nativs [at the mouth of the Columbia] do not eate them, or make any further use of them than in hunting the Elk as has been before observed.[11]Clark, 2 February 1806: “The natives of this neighbourhood have a Small Dog which they make usefull only in hunting the Elk.”

Their description applied only to the dogs they saw in the vicinity of Fort Clatsop, to all dogs west of the Bitterroot Mountains, or to the dogs belonging to all the native people that the Corps met.

On 11 September 1806, twelve days from the end of the expedition, Clark admitted that he as well as most of his men often mistook the barking of coyotes for that of the “Common Small Cur dogs.”

the barking of the little prarie wolves resembled those of our Common Small Dogs that ¾ of the party believed them to be the dogs of Some boat assending which was yet below us. the barking of those little wolves I have frequently taken notice of on this as also the other Side of the Rocky mountains, and their Bark so much resembles or Sounds to me like our Common Small Cur dogs that I have frequently mistaken them for that Speces of dog —

By the end of the 18th century, according to Thomas Bewick, selected cur-dogs or cur-tykes were known to be trustworthy and useful servants to farmers and “graziers.” The cur-dog’s typically black and white coat was short and smooth. Its ears were “half-pricked”—the lower part erect, the upper bent forward.

“Many of them,” Bewick continued,

are whelped with short tails, which seem as if they had been cut: These are called Self-tailed Dogs. They bite very keenly; and as they always make their attack at the heels, the cattle have no defence against them: In this way they are more than a match for a Bull, which they quickly compel to run . . . . They know their master’s fields, and are singularly attentive to the cattle that are in them: A good Dog watches, goes his rounds; and, if any strange cattle should happen to appear amongst the herd, although unbidden, he quickly flies at them, and with keen bites obliges them to depart.

In general they were larger, stronger, and fiercer than most purebred shepherd dogs, but above all, Bewick emphasized, “their sagacity is uncommonly great.”[12]Bewick, Quadrupeds, 286.

A cur-dog did not represent a distinct race or species, but was a mongrel—an animal of obscure parentage—selected from a litter for its potential for training to herd cattle or sheep; hunt rabbits, squirrels, or some game birds; exterminate rodents, or merely to serve as a household companion and watchdog.

From the time of Shakespeare and Addison on, the word cur was also used in a pejorative sense, denoting a worthless, noisy, snappish dog of no recognizable breed. Or worse, “a surly, ill-bred, low, or cowardly fellow.”[13]Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “cur,” 1. and 1b.

Toy Dogs

Thomas Bewick described the Comforter, also known as the Maltese, as “a most elegant little animal, . . . generally kept by the ladies as an attendant of the toilette [dressing-room] or the drawing-room.” According to Bewick known to be “very snappish, ill-natured, and noisy; and does not readily admit the familiarity of strangers.”

Figure 7

The Bichon (Maltese dog)

William Jardine & Charles Hamilton Smith, The Naturalist’s Library. Mammalia. Dogs, (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1860), Vol. 2, 200.

The Bichon or Chien Bouffé, more widely known as the Maltese dog, was, according to Bewick, “the most ancient of the small spaniel races, being portrayed on Roman monuments . . . the muzzle is rounder, the hair very long, silky, and usually white, the stature very small.” Bichons, he wrote condescendingly, were “only fit for ladies’ lap-dogs.”

On the day the Corps of Discovery returned to Travelers Rest (1 July 1806) from the Pacific, Lewis wrote his longest dissertation on prairie dogs, concluding with the remark that “they generally set and bark at you as you approach them, their note being much that of the little toy dogs, their yelps are in quick succession and at each they a[dd?] a motion to their tails.” On the day (7 September 1804) when the captains and some of their men discovered the “burrowing squirrels” that the French engagés called petite chien, Sgt. Ordway remarked that those rodents were indeed “about the Size of a little dog,” although he didn’t name a specific breed.

Of whatever breed, the essential attributes of the canine type recognized as “toy dogs” include small size, friendly disposition, and endearing facial features. It is still a very popular class of pet, especially among older persons, or in densely populated urban neighborhoods, or in bustling commercial neighborhoods where walking one’s dog is inconvenient or inappropriate. Recent genetic analyses have suggested that toy dogs were among the first canids to be domesticated. For many centuries they were symbols of affluence, especially among women of leisure, who used them as hand and foot warmers in chilly salons, theaters, chapels and cathedrals.

From time to time various breeds of toy dogs have become faddish, resulting in over-breeding and potential damage to bloodlines, as was the case with the Mexican chihuahua early in the 21st century. In the era of Lewis and Clark there were fewer than a half dozen distinct breeds of toy dogs; today the American Kennel Club recognizes more than twenty.[14]A Bichon Frise (Fig. 7) was named Best in Show in the 124th (2001) Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show.

Notes

| ↑1 | The metric system was introduced in France in 1799, and is now employed throughout nearly every country in the world except the United States. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In his first dictionary (1806), Noah Webster defined “note” as, for one thing, “a mark,” or “token.” Later, in his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), he was more explicit: “[S]omething by which a thing may be known; a visible sign,” or, in this instance, an audible sound. |

| ↑3 | Jefferson’s preface to Nicholas Biddle‘s History of the Expedition (1814), p. ix. |

| ↑4 | Bewick and Beilby collaborated on the highly successful study, A General History of Quadrupeds, the Figures Engraved on Wood, 4th ed. (Newastle Upon Tyne: S. Hodgson, R. Beilby, and T. Bewick, 1800), 365. Both Bewick and his co-author were engravers, and both working on copper and silver plates. Bewick, however, often incised images into blocks cut across the extremely fine grain of a piece of boxwood—the hardest and finest-grained of all woods—using certain tools borrowed from intaglio engraving in his own technique which became known as “white-line” engraving, in which areas and lines to remain white were cut out of the wood. The block on which the engraving was made was exactly the same thickness as a slug of type, which meant that it could be inked with the same pressure as the surrounding text, as opposed to the increased pressure required to reproduce an image engraved in a copper or steel plate. More importantly, boxwood engravings could be inserted anywhere in the matrix of a given page, whereas copper or steel engravings had to be printed on separate pages owing to the increased pressure they required. The General History appeared in various editions, the most recent being facsimile reprints by three different publishers in 2009, 2010 and 2011. An good modern textbook on the subject is How I Make Woodcuts & Wood Engravings, by Hans Alexander Mueller (New York: American Artists Group, Inc., 1945. Online at http://www.woodblock.com/encyclopedia/entries/011_10/011_10_frame.html. |

| ↑5 | The Rev. William Bingley (1774-1823) published his Animal Biography in 1802, aiming to offset a tendency among the faithful to regard the new popular science of “natural history” as inconsistent with Christian principles. His next work, titled Memoirs of British Quadrupeds (1809) was justified as an effort to illustrate their habits of life, instincts, sagacity, and uses to mankind. |

| ↑6 | Georges-Louis Leclerc, count de Buffon, Histoire naturelle, genérale et particuliére, Vol. 5 (Paris: de L’Imprimérie, 1755), 123. Internet Archive. |

| ↑7 | Captain Thomas Brown, Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs (Edinburgh: Oliver & Boyd, 1829), 418. |

| ↑8 | John Caius, De Canibus Britannicis (London: Gulielmum Seresium, 1570). Translated by William Fleming as Of Englishe Dogges, 1576, reprinted 1729. |

| ↑9 | http://www.ireference.ca accessed on 15 November 2010. |

| ↑10 | Brindle has commonly been used since the late 17th century in describing cattle and, especially, dogs. The American Heritage Dictionary defines it as “tawny or grayish with streaks or spots of a darker color.” |

| ↑11 | Clark, 2 February 1806: “The natives of this neighbourhood have a Small Dog which they make usefull only in hunting the Elk.” |

| ↑12 | Bewick, Quadrupeds, 286. |

| ↑13 | Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “cur,” 1. and 1b. |

| ↑14 | A Bichon Frise (Fig. 7) was named Best in Show in the 124th (2001) Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.