We have heard it said that the Rocky Mountain Sheep

descend the steepest hills head foremost, and they may

thus come in contact with projecting rocks, or fall from

a height on their enormous horns.

The Expedition Library

The ibex (EYE-bex; Latin for goat) is still found in alpine zones from the Alps and Apennines of central Europe eastward to central China, and southward to northern Ethiopia. The species was first identified by Carl Linnaeus as Capra ibex, in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae (1758).[1]Caroli Linnæi, Systema Naturae, . . . Editio Decima, 1758, p. 68, at http://dz1.gdz-cms.de/no_cache/dms/load/img/. Accessed 10 June 2007. The Order in which he placed it, Pecora, is no longer valid in mammalian taxonomy.

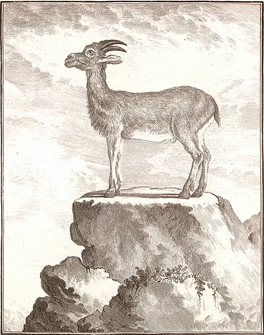

The figure shown above is from Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788), which consisted of thirty-six illustrated volumes, plus eight posthumous volumes by Comte de Lacépède (1756-1825).

Although Meriwether Lewis was, as Jefferson wrote to Benjamin Smith Barton, “no regular botanist &c. he possesses a remarkable store of accurate observation on all the subjects of the three kingdoms, & will therefore readily single out whatever presents itself new to him.”[2]Jefferson to Barton, 27 February 1803; Jackson, Letters, 1:17. Indeed, Lewis’s record of zoological discoveries is impressive, including at least two dozen species and subspecies of animals he believed to be new to science. Moreover, his descriptions were complete enough to enable more fully qualified naturalists to publish definitive taxonomies of those new species. But the expedition’s officers had neither the background nor the resources to reach authoritative conclusions of their own. Their portable reference library definitely contained a copy of John Miller’s 1789 translation of Linnaeus’s two-volume work on botanical taxonomy, and undoubtedly included at least one Linnaean guide to mammals—we don’t know which one—and although Lewis expanded his remarkable talent for minute observation with a working vocabulary of about 200 botanical terms and a great many zoological descriptors, he refrained from assigning taxonomic classifications, with two exceptions.[3]Those two exceptions were, first, Lewis’s guess that the magpie belonged to the “Corvus genus and order of the pica” (17 September 1804), and second, that the eulachon or candle … Continue reading Somewhat surprisingly, it was William Clark who unwittingly injected a dose of confusion into their records of not one but two species of quadrupeds. In short, he and Lewis couldn’t tell a sheep from a goat. More than a century was to go by before all the details came into focus. Meanwhile, the “figures”—the graphic images—of the two bovids evolved toward verisimilitude at a comparable pace.

The Ibex

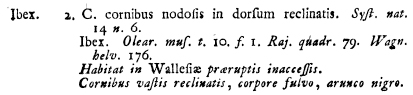

This excerpt from the tenth edition of Linneaus’s Systema Naturae (1758, p. 68), is the description of the class Mammalia; order Pecora; in the genus Capra; the second species, ibex, the “goat with knobby horns that bend over the back.” After citing three previously published sources of information about the ibex—the first a book by the German scholar Adam Olearius (1603-1671) published in 1666, the next two unidentifiable—Linnaeus documented that it “lives in steep, inaccessible places in Hungary,” and that its “hollow horns bend over the animal’s back, the body is dun (brownish gray), the beard is black.”

Linneaus wrote the Systema Naturae in Latin because it was the lingua franca of the educated community, and in that context provided a level playing field for the nascent sciences of zoology and botany. The order Pecora—a Latin word for sheep—is no longer valid. The genus Capra (goat) now falls under the order Arteriodactyla (hoofed, two-toed ungulates), the family Bovidae (ruminants, i.e. grazers with four-chambered stomachs)[4]Although it is often used as a synonym for stomach, paunch properly denotes the first chamber of a ruminant’s stomach, the rumen. The men of the Corps of Discovery, especially the hunters, knew … Continue reading, and the subfamily Caprinae (goat-like, i.e. hollow-horned, bearded ruminants). His original outline allowed for Varietas—Variety—as a subcategory within a species, but that was not yet necessary in the case of C. ibex.

Fort Clatsop Description

Despite the priority of George Kearsley Shaw’s description of the bighorn sheep, and his classification of it as Ovis canadensis, there was disagreement over the animal’s proper scientific identity, and as the 19th century wore on, the picture steadily grew murkier. The few observations on the subject by Lewis and Clark that Nicholas Biddle included in his paraphrase of their journals only served to deepen the confusion.

In the description he edited from Lewis’s Fort Clatsop journal for 22 February 1806, Biddle wrote:

The sheep is found in many places, but mostly in the timbered parts of the Rocky Mountains. They live in greater numbers on that chain of mountains which forms the commencement of the woody country on the coast and passes the Columbia between the falls and rapids. We have only seen the skins of these animals, which the natives dress with the wool, and the blankets which they manufacture from the wool. The animal from this evidence appears to be the size of our common sheep, and of a white color; the wool is fine on many parts of the body, but in length not equal to that of our domestic sheep. On the back, and particularly on the top of the head,[5]Biddle erred; Lewis had written “particularly on the upper part of the neck.” Lewis’s description was based on samples of the skins he had first seen in the possession of Shoshone … Continue reading this is intermixed with a considerable proportion of long straight hairs. From the Indian accounts these animals have erect pointed horns; one of our engagees [engagés] informed us that he had seen them in the Black Hills.[6]Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 vols. (1893; Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, [1965]), 3:850–51

Of course, Lewis was not referring to the bighorn sheep at all, but rather to the mountain goat. Nevertheless, Biddle’s version of Lewis’s description was convincing enough to mislead George Ord, a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, into naming it Ovis montana in his contribution on the new species to Guthrie’s Geography in 1815.[7]Biddle-Allen, 2:170-71. William Guthrie, James Ferguson, and John Knox, A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World, 2nd American ed., … Continue reading Moreover, Biddle had overlooked some small details Lewis provided in his journal entry for the same date, referring to this “sheep’s” coat and horns.

there is no wooll on a small part of the body behind the sholders on each side of the brisquit [chest] which is covered with a short fine hairs as in the domestic sheep. . . . form the signs which the Indians make in discribing this animal they have herect pointed horns, tho’ one of our Engages La Page, assures us that he saw them in the black hills where the little Missouri river passes them, and that they were in every respect like our domestic sheep, and like them the males had lunated horns bent backwards and twisted.

Apparently Lepage was thinking of the bighorn sheep, not the mountain goat. Lewis added, “I should be much pleased at meeting with this animal,” evidently meaning the mountain goat. In fact, they did see the next best thing, although it was not in the flesh, to be sure.

Columbia Gorge Encounter

On 10 April 1806, in a small village of Clahcleller Indians (a branch of the Watlala Chinookans) on the bank of the Columbia where the captains had stopped for breakfast, a resident offered them “a sheepskin for sail, than which nothing could have been more acceptable except the animal itself.” What is more, Lewis recalled,

the skin of the head of the sheep with the horns remaining was cased [skinned] in such manner as to fit the head of a man by whom it was woarn and highly prized as an ornament. we obtained this cap in exchange for a knife, and were compelled to give two Elkskins in exchange for the skin. this appeared to be the skin of a sheep not fully grown; the horns were about four inches long, celindric, smooth, black, erect and pointed; they rise from the middle of the forehead a little above the eyes. they offered us a second skin of a full grown sheep which was quite as large as that of a common deer.

Unfortunately, the Indians sensed the Americans’ eagerness to buy it and, aiming to bargain for a better price, “declared that they prized it too much to dispose of it.” Those people, Lewis continued, “informed us that these sheep were found in great abundance on the hights and among the clifts of the adjacent mountains. and that they had lately killed these two from a herd of 36, at no great distance from their village.” That partly explains the captains’ description of the animal’s habitat, since the village was a short distance below the Cascades of the Columbia; the “adjacent mountains” would have been the Cascade Range. The Clahclellers’ hunters must have bagged it that spring, when mountain goats congregate in large groups at salt licks.

Two days later, on the 12 April 1806, the captains gained further evidence from some congenial Jehuh Indians. They purchased another “sheepskin” from the man who had sold them one on the tenth, who assured them that those animals were “abundant among the mountains and usually resorted [to] the rocky parts.”

Mountain Goats

One easily recognizable distinction between the mountain goat and a true goat is that the latter’s horns sweep up and back, and have spiraled corkscrew-like ridges, whereas the mountain goat’s horns curve back slightly and are smooth. This species (hircus is Latin for he-goat, sometimes in reference to its pungent odor) is believed to have been domesticated in southwestern Asia between 8,000 and 9,000 years ago.

Typically favoring rugged mountaintop terrain in the sub-alpine and alpine zones, especially where nearby cliffs provide safe havens for retreat from predators, this nanny and her kid were photographed on a sunny morning in early August at roughly 11,500 feet above mean sea level, in the Beartooth Mountains, a range that Clark would have observed from the banks of the Yellowstone River, but did not enter.[8]See Clark’s journal entries for 15 July 1806, 18 July 1806, and 24 July 1806. This photograph underscores the main reason Lewis and Clark and their party never saw any live “fleecy goats.” As challenging as their crossing of the Bitterroot Mountains was, they never had reason to pick their way through such inhospitable rock gardens as this, even though Indians had told them that there were “a great number of white buffaloe or mountain sheep [that is, mountain goats] of the snowey hights” of the Bitterroot Mountains.

In contrast with bighorns, mountain goats are resource defenders, remaining in one habitat the year around, usually in alpine or sub-alpine zones. That explains why Lewis and Clark didn’t see any during the entire expedition, although they knew from Indian accounts that they were numerous in the Cascade Range, and they judged from the skins the Indians wore as clothing that the live animals were “of the size of our common sheep, and of a white color.” Furthermore, they judged, “the wool is fine on many parts of the body, but in length not equal to that of our domestic sheep.” Otherwise, they didn’t have any reason to enter the alpine areas in the Bitterroot Mountains. “We have nevertheless,” Lewis declared, “too many proofs to admit a doubt of their existence in considerable numbers on the mountains near the coast.”[9]Biddle-Allen, 1:170.

Mountain goats are not true goats of the genus Capra, but belong in the goat-antelope group, in a tribe called Rupicaprids, of the subfamily Caprinae in the order Artiodactyla (two-toed ruminants). They and their distant relatives, the bighorn sheep, evolved during the recent ice ages along with certain other species, such as the musk ox, that adapted to the extreme cold of the Arctic tundra and the precipitous margins of the ebb and flow of glaciers during the Pleistocene. For that reason, despite the obvious dissimilarities between their coats, their horns, their habitats, and their social habits (goat rams do not butt heads, but may inflict serious damage with their sharp horns), they “occupy the same mountains, endure similar weather, eat much the same food and escape from the same predators.”[10]David Macdonald, The Encyclopedia of Mammals (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1995), 586.

More . . .

Prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, North West Company fur traders had collected Bighorn specimens in the Canadian Rockies (see Earlier Observations). The Lewis and Clark specimens and the journal entries that the Biddle entries provided were part of the source material available to the trained naturalists attempting to place this animal with Linneaus system. Similar to Lewis and Clark, attempts to properly classify the Bighorn Sheep was not without confusion. See Classifying Bighorn Sheep to learn more about that story.

Notes

| ↑1 | Caroli Linnæi, Systema Naturae, . . . Editio Decima, 1758, p. 68, at http://dz1.gdz-cms.de/no_cache/dms/load/img/. Accessed 10 June 2007. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jefferson to Barton, 27 February 1803; Jackson, Letters, 1:17. |

| ↑3 | Those two exceptions were, first, Lewis’s guess that the magpie belonged to the “Corvus genus and order of the pica” (17 September 1804), and second, that the eulachon or candle fish was “of the Malacopterygious Order & Class Clupea” (24 February 1806), which was incorrect. The eulachon does not belong to the genus Clupea (CLOO-pee-uh), which is occupied by 200 species of herrings. Instead, it is a species of smelt, which was classified in 1836 as Thaleichthys pacificus (thal-ee-IK-this pa-SIF-i-kus) by the Scottish surgeon, naturalist and explorer Sir John Richardson (1787-1865). For an overview of Lewis’s achievements in his observations and descriptions, see Paul Russell Cutright, Lewis and Clark, Pioneering Naturalists (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1969), 261-63. |

| ↑4 | Although it is often used as a synonym for stomach, paunch properly denotes the first chamber of a ruminant’s stomach, the rumen. The men of the Corps of Discovery, especially the hunters, knew well what it was. They were astonished to see Sioux Indians use a deer or buffalo paunch to carry water, “in the same condition, as it is taken from the Animal” (Whitehouse, 27 September 1804). Several of the undernourished Lemhi Shoshone men, “like a parcel of famished dogs,” shared the raw paunch of a freshly killed deer, squeezing the contents out as they ate” (Lewis, 16 August 1805). A few weeks later they watched Toby and his son “Eat the paunch and all the Small guts of the Deer” (Whitehouse, 4 September 1805). The Nez Perce ate the paunches of deer “without any preperation other than washing them a little” (Clark, 6 May 1806). |

| ↑5 | Biddle erred; Lewis had written “particularly on the upper part of the neck.” Lewis’s description was based on samples of the skins he had first seen in the possession of Shoshone Indians in August 1805. |

| ↑6 | Elliott Coues, ed., The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, 3 vols. (1893; Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, [1965]), 3:850–51 |

| ↑7 | Biddle-Allen, 2:170-71. William Guthrie, James Ferguson, and John Knox, A New Geographical, Historical and Commercial Grammar and Present State of the Several Kingdoms of the World, 2nd American ed., improved (Philadelphia: Johnson & Watner, 1815). |

| ↑8 | See Clark’s journal entries for 15 July 1806, 18 July 1806, and 24 July 1806. |

| ↑9 | Biddle-Allen, 1:170. |

| ↑10 | David Macdonald, The Encyclopedia of Mammals (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1995), 586. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.