But ask the animals,

and they will teach you.

Bighorn Sheep Caravan

Near Moab, Utah

© 2005 Jim Bouldin. Permission to use granted under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.

Antiquity

This petroglyph representing a desert bighorn sheep is believed to have been etched into this rock in the Coso Range of the Sierra Nevada Mountains between about 200 BC and 1300 AD. The actual meaning of the many ancient images of bighorn sheep that are still to be seen in the West is uncertain. Some archaeologists believe they may have been objects for veneration, meant to invoke the power and might as symbolized by their large horns. For similar reasons, thousands of bighorn rams have been killed for their trophy heads alone, especially toward the end of the 19th century,[1]A herd of bighorn sheep that has roamed on and around Sheep Mountain, at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clark Fork Rivers near Missoula, Montana, since before local memory began, suffered three … Continue reading just as bull elk were hunted nearly to extinction purely for the mere sake of their teeth. The bright orange lichen in this photo is probably a species of Caloplaca; the yellow-green may be Vulpicida tilesii.

Fossil evidence suggests that sometime during the Pleistocene Epoch, a large number of hoofed, even-toed ruminant mammals with multiple stomachs began to evolve, more or less in the company of other boreal species such as the woolly mammoth, the bear, the reindeer, and many others. In North America the process probably began at the margins of glacial ice fields; in due time the species now known as the bighorn sheep evolved to inhabit a vast region extending from the Brooks Range in Alaska to the mountains and deserts of the Southwest.

At some unknown time and place our own primordial ancestors, Homo sapiens, began to identify, and perhaps to revere, some of the other animals that shared the Earth with them, especially those they felt attachments to by virtue of their proven utility as food and clothing. There is no reason not to assume that those early people eventually gave names to at least the ones that were most important to them, including the bighorn sheep, and they memorialized that importance with images scratched into or painted on cliffs, cave-walls, and rocks (fig. 1).

During the Middle Ages, Job’s doctrine, “In his hand is the life of every creature and the breath of all mankind” (12:10), was summarized and illustrated in books called bestiaries. These were manuscript collections, on parchment, of allegories based on passages from Scripture, explaining the symbolisms of certain attributes of various animals and birds. The ibex played an important role in that lore (fig. 2).

Native Americans

Figure 2

Ibex

The Royal Library of Denmark.

From The Bestiary of Anne Walshe[2]The Bestiary of Anne Walshe, so called because her signature is present on several pages, is one of the more than fifty medieval bestiaries still extant. It is thought to have been produced in … Continue reading

English, early 15th century

This illustration was supposed to represent the ibex or wild goat ram of the Alps and Apennines. He is poised to leap from his mountaintop home to the valley below, where he would land on his horns, which were believed to be so strong that he would escape injury. Judging from the figure’s horns, exaggerated tail, and defiant visage, the artist had never left his (or her) scriptorium to observe an ibex in the flesh, and the verbal description must have emphasized those great horns at the expense of other details. In some bestiaries the ibex was portrayed with huge horns pointed forward.

But neither good art nor good science was the point. The picture was an exercise in pure imagination, sufficient only to illustrate a timely homily. The ibex, this scribe wrote, “represents those learned men who are accustomed to manage whatever problems they encounter with the harmony of the two Testaments as if with a sound constitution; and, supported as by two horns, they sustain the good they do with the testimony of readings from the Old and New Testament.”

For many thousands of years the Native peoples who lived in far-western North America had their own names for it.

The first Euro-Americans who penetrated the Rocky Mountains from the south and the east wrote down approximate transliterations of Indians’ various names for it. The Crees of the Canadian West called it My-Attic, or “ugly reindeer.” Bloods, Piegans and Blackfeet knew it either as E-mah-k”-kin-i, “bighead,” or Ema-ki-ca-now, “a kind of deer.” To the Mandans it was Ar-sar-ta (in William Clark‘s phonetic spelling) or ·se xte, also translated as Ansa-chta, “big horn”; to the Hidatsas the name may have sounded nearly the same, Azichtia. The Arikaras called it Arikusa; the Slave Indians called it Sass-sei-yewneh, or “foolish bear”; the Hopi, Pan’g-wuh, (translation unclear). Spanish explorers called it Cimarron, or “wild (sheep)”; their French Canadian counterparts eventually dubbed it variously Belier Sauvage de Montagne, Grosse Corne, and Cul-blanc—respectively, “wild ram of the mountains,” “big horn,” and “white rump.” It was the confusion inherent in mélanges of common names like these that Linnaeus aimed to replace with a logically deduced, universally valid nomenclature.

Spanish

In 1540 the Spanish conquistador Francisco Vázquez de Coronado wrote a letter to Governor Mendoza of Mexico describing what he had seen during his futile search for the seven fabulous cities of Cibola, a quest that had drawn him from Mexico into the present southwestern United States and lower California. Among the wildlife he had heard of were “some Sheep as big as a Horse, with very large horns and little tails.” He had seen some of their horns, “the size of which was something to marvel at.”

More than 150 years later, in 1702, Father Francis Maria Piccolo, the historian for a group of five missions the Jesuits had established on the Lower California peninsula, again reported on the remarkable horned sheep.

Besides several sorts of Animals that we knew, which are here in plenty, and are good to eat, as Stags, Hares, Coneys, and the like; we found two sorts of Deer, that we knew nothing of: We call them Sheep, because they somewhat resemble ours in make. The first sort is as large as a Calf of one or two Years old: Its Head is much like that of a Stag; and its Horns, which are very large, like those of a ram: Its tail and Hair are speckled, and shorter than a Stag: But its Hoof is large, round, and cleft as an Oxes. I have eaten of these Beasts; their Flesh is very tender and delicious.[3]Quoted in Ernest Thompson Seton, Lives of Game Animals, 4 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1925-28), 3:512.

Another half-century elapsed before, in 1758, another Mexican Jesuit, Father Miguel Venegas, published Fr. Piccolo’s description of the strange-looking but tasty animal along with its earliest known picture from life (Fig. 3), plus its Monqui Indian name, “The Tayé or California Deer.” Nearly thirty more years went by before the Welsh naturalist and antiquary Thomas Pennant decided the American bighorn was really an Argali, reinterpreting the Fathers Piccolo and Venegas.[4]Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), Arctic Zoology, 2 vols. (London: Printed by H. Hughs, 1784-85), 1:13. An antiquary at that time was a student or collector of antiquities–relics of early history. And so on for several more decades, one naturalist after another invoking the same venerable authorities.

North West Company

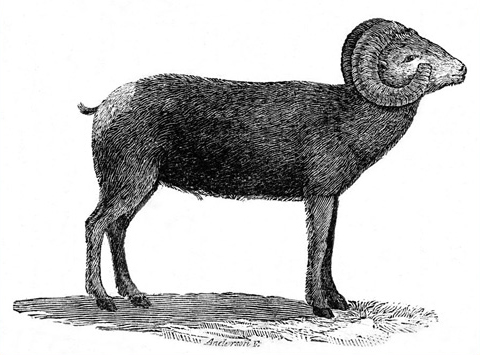

Figure 4

First Figure

The Medical Repository (1803). Ewell Sale Stewart Library, Academy of Natural Sciences.

This mezzotint engraving signed by “E. Anderson,” may have been based on a painting by the “Mr. Savage,” who had personally delivered McGillivray’s letter to Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill, the founder and director of the Lyceum of Natural History in New York City, along with a hide and perhaps a head or skull with horns. That courier probably was Edward Savage (1761-1817), a New York artist whom Mitchill claimed had already made two good paintings of the Lyceum’s specimen. A nearly identical figure with a timid hint of a rocky mountain in the background appeared in the first American version (1804) of Thomas Bewick’s book for young readers, A General History of Quadrupeds.[5]The producer of the book, Alexander Anderson (1775-1870), was a New York graphic artist whose specialty was relief engraving across the grain on box-wood blocks. Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) was the … Continue reading Obviously, Savage’s figure was an improvement over Fr. Venegas’s crude doodle (Fig. 3), but it was still a ram’s head on a deer’s body with a white rump and a perky little tail. Consistent with the style of most zoological figures at that point in time, it was a lifeless graphic “mug shot” contrived from an incomplete specimen. Little by little, more would be revealed.

Some biologists have speculated that the tips of an old ram’s full-curl horns, normally pointed, are often “broomed,” that is, broken or rubbed off—like this one’s evidently were when they began to interfere with his peripheral vision. Others believe the abridged horns are entirely a result of the vigorous head-butting contests between competing rams. Notice that Fr. Venegas’s likeness also apparently represented an old ram whose horns had been broken at their tips. Perhaps artists’ early fascination with those fractures arose from the medieval legend of the lifesaving utility of the Alpine sheeps’ horns, supposedly corroborated by the distant sounds of the rams’ cranial clashes.

Why was the preposterous Medieval legend about the purpose of those big horns still around in the 1840s? Perhaps, in the absence of more extensive observations of the animal’s habits, it just seemed more reasonable than imaginary animal rage, frustration, or clumsiness. After all, a bighorn ram looks heavy in its forequarters, and the law of gravity would ordain that in a fall the head end would hit first, with that emergency landing gear bearing the brunt. Then there’s that resonant thwock of hollow horns when pairs of fighting rams butt foreheads at a combined speed of perhaps forty miles per hour! It all still seemed to add up.

Some research during the 1960s seemed to suggest that horns in all bovids function as thermoregulatory organs, emitting body heat during exertion or in summer temperatures, and conserving it in winter, but it now appears more likely that the large horns probably evolved as symbols of rank and breeding success.[6]Geist, Mountain Sheep, 176-83. Similarly, certain Indian tribes once recognized rams’ horns as status symbols too. Lewis and Clark nicknamed the Nez Perce leader We-ar-koomt “the bighorn Cheif” from the circumstance of his always wearing a horn of that animal suspended by a cord to [his] left arm.”[7]Lewis, 3 May 1806.

Late in November 1800 a small group of explorers led by Duncan McGillivray, a clerk for the North West Company of Montreal, and David Thompson, a fur trader, surveyor and mapmaker for the same outfit, took a break on the bank of the Bow River to rest their horses. Noticing what looked like a small herd of deer in the distance, McGillivray and his Indian guide hurried on ahead to bag some fresh meat for their eight-man party. When they came within firing range the Scotsman realized he had never seen their likes before, so he approached to within about sixty yards of the little group, “examining them with all the curiosity that is natural for a man to feel on seeing any unusual appearance.” He soon shot a male of “superior size and enormous horns,” and immediately took its measurements: “length from the nose to the root of the tail, five feet; length of the tail, four inches; circumference round the body, four feet; they stand three and three quarters feet high; length of the horn, three and an half feet; and girth at the head one and a quarter feet.” That afternoon he and his Indian guide killed four more of the beasts.

While McGillivray was dressing out the carcass of his first big ram, David Thompson was taking celestial observations with his sextant to determine the meridian altitude of the sun, by which he could calculate the latitude and longitude of their location,[8]It was 50°00’00” North, 115°30’00” West, which is roughly 72 miles south and 64 miles west of today’s Calgary, Alberta. a detail that would be useful to him in completing his map of that still uncharted region. He also recorded a few of his own remarks on those “Mountain Goats,” noting their strength and agility, and the soft-centered hooves that enabled them to retreat up nearby cliffs for safety. Finally, with a hint of anthropomorphic sympathy combined with a touch of male chauvinism, he observed,

The She Goats have a simple mild Look, and are curious to approach and examine with their Eyes whatever they see moving, if it does not appear in too formidable a Shape; the Bucks divested of their Horns would have nearly the same Appearance, but their large weighty Horns superior size & Strength and more ardent curiosity, which makes them advance before the Herd, give them an Air [of] daring with a Dash of the Formidable.[9]29 November 1800. David Thompson’s extensive daily journals, covering 27 continuous years of travel, exploration, and mapping of northwestern North America from Montreal to the mouth of the … Continue reading

Neither McGillivray nor Thompson reported how many more of the My-attic they killed that winter, nor did they say whether they tried to preserve any complete skeletons or intact heads, but the skins of at least two of the carcasses were carefully cleaned and dried. If they could be kept free of maggots and other vermin en route, they could be carried back to civilization where, with a general description of the live animal plus its principal measurements, they would suffice as a basis for an experienced artist or engraver to create a reasonable likeness.

McGillivray’s Description

McGillivray recounted the tale of his encounters with the mountain sheep in a letter to Dr. Mitchill, who published it in The Medical Repository.[10]The Medical Repository, the first scientific journal in America, was published quarterly from 1797 until 1824. It was founded by three members of a gentlemen’s club in New York City, including … Continue reading The letter contained a detailed text, or “diagnosis” of the animal, which included the measurements of the first one McGillivray shot and a comparison with other similar quadrupeds in terms of shape and color (note the “timid, good-natured cast of the countenance” of the female)—very important details to any artist who sought to create an accurate depiction or “figure”—plus some general observations as to its habitats and habits, and finally its appeal to the human palate:

It is only to be met with in the rocky mountains, and generally frequents the highest regions which produce any vegetation; though sometimes it descends to feed at the bottom of the valleys, from whence, on the least alarm, he retires to the most inaccessible precipices, where the hunter can seldom follow him. His appearance, though rather clumsy, is expressive of active strength, and the nimbleness of his motion is surprising. He bounds from one rock to another with as much facility as the goat, and makes his way through places quite impracticable to any other animal in that country without wings.

The female does not differ materially from the male, except that her size is much less, and she has only a small black straight horn like the goat. The colour and texture of the hair is the same in both, and they are all distinguished by the white rump and dark tail. In other respects the female greatly resembles the sheep in her general figure, and particularly in the timid, good-natured cast of the countenance. In winter they frequent the southern declivity of the mountains, to enjoy the sunshine; the lower regions, and the valleys, at that season, being covered with a great depth of snow.

The flesh of the female, and of the young male, is a great dainty; for my own part, I think much more delicate than any other kind of venison: and the Indians, who live entirely on animal food, and must be epicures in the choice of flesh, agree that the flesh of the My-attic is the sweetest feast in the forest.[11]“Memorandum respecting the Mountain Ram of North-America. by Duncan M’Gillivray. Communicated to Dr. Mitchill by Mr. Savage, in a Letter, dated New-York, November 24, 1802,” in … Continue reading

All this was hardly a secret. Word got around among the scientific cognoscenti in Europe as well as America. Benjamin Smith Barton knew that Spanish historians had mentioned the species before 1633. Moreover, in a letter to Jefferson Caspar Wistar referred to McGillivray’s account of the “Wild Sheep” as if both of them had seen the article in The Medical Repository.[12]Wistar to Jefferson, 13 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 1:108. Lewis was on the road from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh at the time. He might have gotten wind of McGillivray’s account from … Continue reading Yet in a later exchange between Jefferson and the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède, Jefferson seemed not to have remembered it. Whether Lewis knew of all this is uncertain, but it seems likely that he did, being well within Jefferson’s enlightened social and scientific orbit.

Shaw’s Ovis canadensis

Figure 5

Dr. George Kearsley Shaw

Botanist and Zoologist

Smithsonian Institution. Engraving, 10.3 x 7.7 cm (4 x 3 in.) Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology, Smithsonian Institution.

Shaw’s 1804 Description

Generic Character

Horns hollow, wrinkled, turning backwards, and spirally intorted [twisted or curled inwards].

Front-Teeth eight in the lower jaw.

Canine-Teeth none.

Specific Character

Ferruginous-brown hairy SHEEP, with white front and rump, very short tail, and compressed lunated [crescent-shaped] horns.

Bélier de Montagne [mountain ram].

Geoffr. ann. mus. nat. No. 11. p. 300.

Late in 1803, doubtless working from McGillivray’s text and the dried skin he had carried to England from New York, the prominent British physician and naturalist George Kearsley Shaw (1751-1813), of the natural history department at the British Museum, published an official scientific description along with a proper binomial identifying the genus and the species, Ovis canadensis—Canadian sheep, because Canada was the source of the type specimen—and a hand-colored engraving by Richard Polydore Nodder (fig. 6):

The species of sheep here represented, and which appears to have been, till very lately, unknown to the naturalists of Europe, is a native of the interior parts of Canada. It is remarkable for being covered, instead of wool, with very thick and strong hair, greatly resembling that of a Deer. The legs are long in proportion to the body. The horns very much resemble those of the common ram, and those of the female are said to be much smaller than those of the male. The general colour is a pale ferruginous brown, similar to that of many of the Deer tribe: the cheeks are of a darker cast than the other parts, and the muzzle and rump are white: the tail is very short. The general habits of the animal are said to resemble those of the Ibex, frequenting chiefly the highest and most inaccessible parts of the mountainous regions, occasionally skipping from rock to rock with incredible swiftness. It is generally observed in small flocks of twenty or thirty together, and is known to the Canadians by the name of Mountain Sheep. The young are considered as the most delicate meat which that extensive country can afford [i.e. provide]. A very fine specimen of this rare quadruped may be seen in the British Museum.[13]George Kearsley Shaw, The Naturalist’s Miscellany: Or, Coloured Figures of Natural Objects; Drawn and Described Immediately From Nature (1789-1813), 2:57.

Note that Shaw, who so far as we know had only the hide and horns of a “Canadian sheep” ram before him, compared its hair with that of a deer, and from only hearsay likened its habits and habitat to those of the Ibex. On the one hand, those ostensibly superficial comparisons suggested providential design, and were consistent with the ongoing search for links in the Divine chain. At the same time, Shaw’s diagnosis was undisciplined. No wonder a younger critic judged his General Zoology to be a “sinker,” and its author “one of the dullest and least respectable” of all British naturalists.[14]Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-56), “Audubon’s Quadrupeds of North America,” The American Review, A Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art and Science, 4 (December 1846): 632. … Continue reading The natural sciences were ripe for the revolutionary concepts of a Georges Cuvier.

Nodder’s Drawing

Nodder presents the bighorn in a nondescript outdoor setting that contains scarcely a hint as to the type of terrain it navigates with apparent nonchalance, and which the British artist more than likely could scarcely imagine. It would be many years before someone would record the observation that a bighorn could find a secure foothold on a ledge only a few inches wide, and gracefully leap twenty feet or more from one ledge to another. Not surprisingly, however, they do have accidents, and since they do not necessarily land on their horns, one cause of mortality is a broken leg with consequent death by starvation.

It was understood, of course, that whereas the description was based on information from a person who had seen the bighorn, the drawing was made from a dead specimen, or parts thereof. The background in this instance, which probably would have been filled in by an assistant, enhances the supposedly naturalistic illusion.

On the whole, Shaw’s treatment of the Canadian Sheep reflected the inadequacy of most European “cabinet,” or laboratory-bound, naturalists’ qualifications to deal with recently discovered North American wildlife.

Geoffroy’s “sheep-deer”

Another naturalist who was indebted to McGillivray was Etienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire (1772-1844), who in 1803 published his French paraphrase of the Scotsman’s account of the mountain sheep, naming it anew, Belier de Montagne–”mountain ram”–,[15]Etienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire (1772-1844), ‘Description d’une nouvelle espèce de belier sauvage de l’Amérique septentrionale,’ Annales du Muséum national d’histoire … Continue reading and accompanied it with a figure based on Savage’s engraving (fig. 4). Early in 1804, Geoffroy’s version of McGillivray’s description, along with a second- or third-generation figure based on Savage’s drawing, became the basis of the new name for the species that the French zoologist Desmarest added to the mix, Ovis cervina–”sheep-deer,” with nearly all of his description quoted verbatim from Geoffroy.[16]Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (1784-1838), in ‘Nouveau Dictionnaire d’Histoire Naturelle,’ Tome XXIV, An. Xii (1804), 5-6.

Thompson’s Observations

A generation later, the English naturalist David Douglas published his personal observations on two quadrupeds that he said were “previously undescribed,” the white-tailed deer and the bighorn sheep. After repeating Meriwether Lewis‘s dimensions of the bighorn, and detailing the characteristics of its horns and coat, he recounted an Indian informant’s impression that the species was most numerous in the mountains of California. That explains the new specific epithet that he added to the still-simmering mixture of names–californianus. “Of the manners of this majestic animal I can say nothing,” Douglas confessed, “never having had an opportunity of seeing it alive.” In fact, he admitted, [t]he only good skin that ever came under my observation was that of a male, apparently recently killed,” which he had come across on 27 August 1826. He even noted the map coordinates of its location on the east slope of Mount Adams, in south-central Washington. He tried to barter for the skin with the Indians who had bagged it, but their price was too high, so for “a few trinkets and a little tobacco” he settled for the horns only, which he subsequently donated to the Museum of the Zoological Society of London.[17]David Douglas (1799-1834), “Observations of Two Undescribed Species of North American Mammalia,” Zoological Journal, vol. 4 (1829), 332.

But the story is not yet half-told. Getting to know the bighorn sheep intimately was to be the work of many more years-worth of pursuit, study and speculation. See Classifying Bighorn Sheep to learn more about that story.

Notes

| ↑1 | A herd of bighorn sheep that has roamed on and around Sheep Mountain, at the confluence of the Blackfoot and Clark Fork Rivers near Missoula, Montana, since before local memory began, suffered three fatalities from trophy poachers in 2006. Thanks to an anonymous tipster, seven local individuals were charged in the case during the summer of 2007. Among them, three young males age 21, 18, and 15, were fined a total of $4,620 and lost their hunting and fishing privileges for a total of more than 16 years, with one also sentenced to five days in jail, and one to five days of work release. Poaching of bighorn sheep is rare, the Missoulian (21 July 2007) quoted a game warden as saying. “They are an animal that is highly valued by the public and sportsmen.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Bestiary of Anne Walshe, so called because her signature is present on several pages, is one of the more than fifty medieval bestiaries still extant. It is thought to have been produced in England during the first quarter of the fifteenth century. It is now in the collection of the Royal Library in Copenhagen, Denmark. See http://bestiary.ca/articles/anne_walshe/index.html. |

| ↑3 | Quoted in Ernest Thompson Seton, Lives of Game Animals, 4 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1925-28), 3:512. |

| ↑4 | Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), Arctic Zoology, 2 vols. (London: Printed by H. Hughs, 1784-85), 1:13. An antiquary at that time was a student or collector of antiquities–relics of early history. |

| ↑5 | The producer of the book, Alexander Anderson (1775-1870), was a New York graphic artist whose specialty was relief engraving across the grain on box-wood blocks. Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) was the first great British wood engraver, whose reputation rested chiefly on the engravings he produced for his General History of Quadrupeds (London, 1790). Anderson reprinted Bewick’s text in 1804, with re-engravings of Bewick’s images. Anderson’s edition included an appendix containing “some American animals not hitherto described,” which Samuel Mitchill enumerated in the first volume (1804) of his Medical Repository as “the shy hamster of Georgia, the fossil mammoth skeleton of New-York, the wild sheep of Louisiana [fig. 4, above], and the strange vivo-oviparous shark of Long-Island.” |

| ↑6 | Geist, Mountain Sheep, 176-83. |

| ↑7 | Lewis, 3 May 1806. |

| ↑8 | It was 50°00’00” North, 115°30’00” West, which is roughly 72 miles south and 64 miles west of today’s Calgary, Alberta. |

| ↑9 | 29 November 1800. David Thompson’s extensive daily journals, covering 27 continuous years of travel, exploration, and mapping of northwestern North America from Montreal to the mouth of the Columbia River, remained almost entirely unknown for nearly 200 years until Barbara Belyea edited some of them in David Thompson: Columbia Journals (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994). Thompson’s journals were meant more as notes for his own use and to draw maps for his employer, than as reports to a waiting public and its government, as were Lewis and Clark’s. During the height of the Canadian fur trade the company would have guarded much of their employee’s discoveries as privileged information. But when the industry began to decline at mid-century, Thompson’s experiences in the West were of little interest to the general public. He himself wrote a long account of his sojourn in the West, one of the drafts of which was finally published 59 years after his death as David Thompson’s Narrative of his Explorations in Western America, 1784-1812, edited by Canadian geologist Joseph Burr Tyrrell (Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1916). Thompson’s comments on the bighorn sheep did not make the cut for his own memoir. |

| ↑10 | The Medical Repository, the first scientific journal in America, was published quarterly from 1797 until 1824. It was founded by three members of a gentlemen’s club in New York City, including Samuel Latham Mitchill, who was its editor until 1820 when he was appointed professor of materia medica and botany in the College of Physicians at Philadelphia. Although the Repository was primarily devoted to medical matters, beginning with studies of epidemics in its early years, consistent with the broad scientific focus of the medical profession, the magazine frequently included articles on botany and zoology, as well as physical geography, chemistry, mineralogy, and meterology. At the outset its subscription list consisted of fewer than three hundred names, but that number undoubtedly increased during the ensuing decades as the appeal of such magazines widened, with the Medical Repository outlasting many competitors. Frank Luther Mott, A History of American Magazines, 5 vols. (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1938-68), 1:149, 199, 215-17. In keeping with common practice in the day’s media, McGillivray’s letter was published first in the New York Daily Advertiser on 4 December 1802. |

| ↑11 | “Memorandum respecting the Mountain Ram of North-America. by Duncan M’Gillivray. Communicated to Dr. Mitchill by Mr. Savage, in a Letter, dated New-York, November 24, 1802,” in “Account of the Wild North-American Sheep,” The Medical Repository (Philadelphia), Vol. VI, No. 3 (February 1803), 237-40. Apparently McGillivray was not in the vicinity of any bighorn bands during the fall rutting season, for he did not mention seeing or hearing the head-butting contests among rams, in which they pair off and charge one another at speeds estimated above 20 mph, colliding their foreheads with a gunshot-like crack that can be heard up to a mile away. |

| ↑12 | Wistar to Jefferson, 13 July 1803. Jackson, Letters, 1:108. Lewis was on the road from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh at the time. He might have gotten wind of McGillivray’s account from acquaintances in Pittsburgh during the two months he spent there waiting to take command of his custom-built barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’), but there is no known evidence to prove that. |

| ↑13 | George Kearsley Shaw, The Naturalist’s Miscellany: Or, Coloured Figures of Natural Objects; Drawn and Described Immediately From Nature (1789-1813), 2:57. |

| ↑14 | Charles Wilkins Webber (1819-56), “Audubon’s Quadrupeds of North America,” The American Review, A Whig Journal of Politics, Literature, Art and Science, 4 (December 1846): 632. Shaw’s General Zoology (1800-1826) ran to 14 volumes. |

| ↑15 | Etienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire (1772-1844), ‘Description d’une nouvelle espèce de belier sauvage de l’Amérique septentrionale,’ Annales du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle,’ Tome II, An XI (1803), 360-363, pl. lx. |

| ↑16 | Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest (1784-1838), in ‘Nouveau Dictionnaire d’Histoire Naturelle,’ Tome XXIV, An. Xii (1804), 5-6. |

| ↑17 | David Douglas (1799-1834), “Observations of Two Undescribed Species of North American Mammalia,” Zoological Journal, vol. 4 (1829), 332. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.