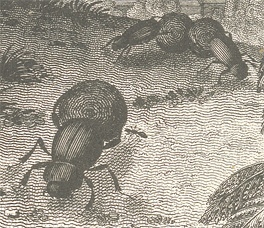

Tumblebugs

Dung Beetles

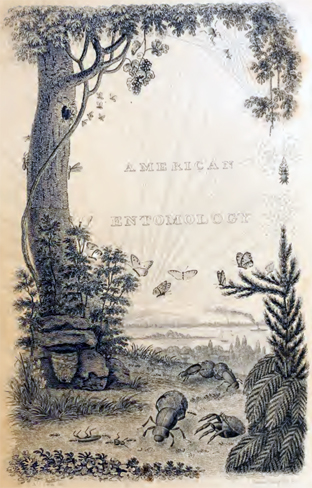

American Entomology Frontspiece

Thomas Say, American Entomology: or Descriptions of the Insects of North America (1824-28), drawn by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur.

The frontispiece to Thomas Say’s American Entomology: or Descriptions of the Insects of North America (1824-28), drawn by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur, presents two insects that were of primary interest to Americans throughout most of the 19th century. Sprightly butterflies embodied nature’s purest, most delicate beauty; tumblebugs once were recognized as nature’s most industrious and beneficial laborers in farmyards, fields and roadways.

The latter, also known as dung beetles or scarab (from a Latin word for “crab”) beetles, stand more or less upside down on their forelegs, and push balls of dung backwards to their subsurface nests with their hind legs. The balls were used as brooding nests, and were consumed as food and drink by the offspring. Either way, they benefit the soil by incidentally recycling nutrients that fertilize the soil, with benefit to grasses that will feed the next generation of ruminants and equines, which will produce more dung, and the cycle continues.

Dung beetles were especially useful in the age when most work and transportation was done by horses, mules, and oxen, horses alone excreting an average of 50 pounds of manure every day, or nine tons per year.[1]Betsy Wieland, “Horse Manure Management and Composting,” University of Minnesota Extension, http://www.extension.umn.edu/horse, (accessed 15 January 2010). It’s hard to imagine how deep in dung the world would be without vast numbers of these beetles to handle the recycling.

Dung Beetles at Long Camp

The Corps of Discovery crossed the Snake River on 4 May 1806, fully aware they would have to bide their time in Nez Perce country until after the next full moon, which was due on the first of June. On 30 May 1806, Lewis wrote his 261-word catalog of the insects that had been observed throughout the expedition to date, with only a few additional remarks. After opening with the statement that “most of the insects common to the U’ States are found here,” he listed “the butterflies, common house and blowing flies,” as well as horse flies, “except the goald coloured ear fly, tho’ in stead of this fly we have a brown coloured fly about the same size which attaches itself to that part of the horse and equally as troublesome.” He then wrote that “a great variety of beatles common to the Atlantic states are found here likewise,” except that “the black beatle usually [c]alled the tumble bug which are not found here.” Lewis’s last remark seems hard to justify.

Given the numbers of horses that the Nez Perce people owned, it seems highly unlikely that dung beetles were entirely absent. The Nez Perce may have begun to acquire horses within a few years after the Pueblo uprising of 1680 against Spanish control in the American southwest, when the Pueblos captured the Spaniards’ horses to impede their owners’ escape, and soon began to dispose of them in trade with tribes farther north.[2]Allen V. Pinkham and Steven R. Evans, Lewis and Clark Among the Nez Perce: Strangers in the Land of the Nimiipuu (Washburn, North Dakota: Dakota Institute Press, 2013), 14. If the dispersal of Spanish horses was slower than that, it is generally agreed that most tribes on the northern plains had begun to breed them by about 1730. In either case, horses had few if any natural predators beyond mountain lions, and their natural re-population rate has been calculated by the Bureau of Land Management at roughly 18 percent.

Since Lewis was nominally the master of a 2,000-acre plantation back in Virginia, he certainly knew what at least one species of dung beetle looked like, so it may be that he didn’t recognize the species he saw. There is one plausible excuse for his failure to identify any at all. There are three varieties of dung beetles: rollers, tunnelers, and dwellers. The rollers pictured here by Monsieur Lesueur in a misleading perspective that makes them appear much larger than life. North American species range up to 20 millimeters (eight tenths of an inch) in length. Therefore we can only suppose that the one that was common to the Nez Perces’ homeland were either the secretive tunneler or dweller who hides in the dung itself.

Notes

| ↑1 | Betsy Wieland, “Horse Manure Management and Composting,” University of Minnesota Extension, http://www.extension.umn.edu/horse, (accessed 15 January 2010). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Allen V. Pinkham and Steven R. Evans, Lewis and Clark Among the Nez Perce: Strangers in the Land of the Nimiipuu (Washburn, North Dakota: Dakota Institute Press, 2013), 14. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.