View of pyramidal Table Mountain (left center) north of the Columbia River in present Washington State, showing the scars of the cataclysmic Bonneville rock slide-debris avalanche at the Cascades of the Columbia. Described by Clark on 1 November 1805, as a “low mountain Slipping in on the Stard Side,” the Bonneville landslide completely crossed the Columbia River and created a temporary lake that flooded tens of miles of upstream riverside woodlands, which produced the submerged forest first documented by Lewis and Clark.

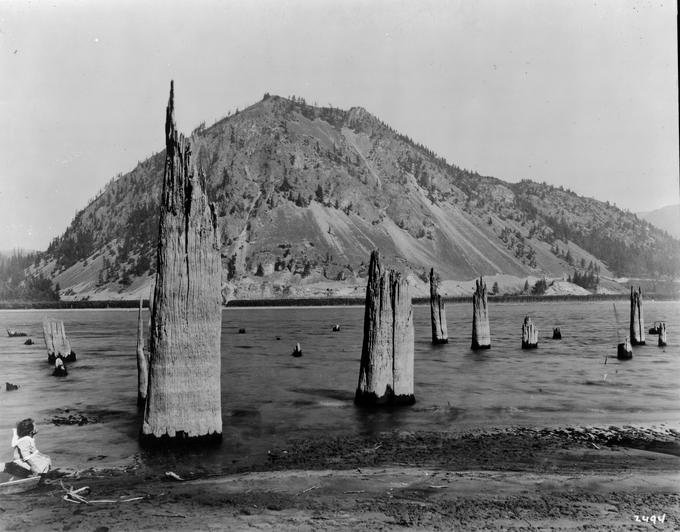

Submerged Forest at Wind Mountain

ORU_PH037_0264: Tree trunks of submerged forest in Columbia River, Angelus Studio Collections, ph037, Special Collections &University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, Oregon.[2]Although no date or photographer information was affiliated with this photograph in the archives, this image resembles another photograph of the submerged forest held by the Oregon Historical Society … Continue reading

Historical photograph of the submerged trees (with Wind Mountain visible in the background), described by William Clark on 30 October 1805, as “many Stumps bare in & out of the water.” Geologic studies, radiocarbon dating, and dendrochronology research indicate the trees died between AD 1425 and 1450, dating the Bonneville landslide that caused their inundation to roughly 350 years prior to the arrival of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Columbia River Gorge Landslides

Some of the captains’ observations through the Columbia River Gorge correctly ascertained the causes or sources of several key catastrophic events, not from the distant geologic past, but recent enough to be recalled in Native American oral histories.

Across the river from the “4 Cascades,” Clark noted evidence of a landslide off the southern slopes of present-day Dog Mountain:

[30 October 1805:] passed Several places where the rocks projected into the river & have the appearance of haveing Seperated from the mountains and fallen promiscuisly into the river, Small nitches are formed in the banks below those projecting rocks which is comon in this part of the river.[3]When Clark mentioned “Small nitches are formed in the banks below those projecting rocks,” one can refer back to his Elk-skin-bound journal for clarification and see that he was … Continue reading

Clark’s observation in his Elkskin-bound journal that these rocks had “fallen from the highe hills,” may have helped set in his mind a mental image of the instability of this mountainous Gorge terrain. If so, this may have enabled him to recognize evidence of monumental mass earth movements the expedition was to encounter at the Cascades.

A Submerged Forest

On 30 October 1805, Clark documented the presence of a submerged forest, which along with the burning bluffs of northeastern Nebraska, the “Burnt Hills” of North Dakota, and White Cliffs of the Missouri in central Montana, remain one of the expedition’s most famous geological observations.[4]Discussions of these noteworthy geological observations can be found in, respectively, John W. Jengo, “‘Blue Earth,’ ‘Clift of White’ and ‘Burning Bluffs’: … Continue reading Clark noted:

a remarkable circumstance in this part of the river is, the Stumps of pine trees are in maney places are at Some distance in the river, and gives every appearance of the rivers being damed up below from Some cause which I am not at this time acquainted with.

This information was considered meaningful enough to be mentioned in the 1830 edition of British geologist Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology, the only expedition-related observation to merit inclusion in that seminal book.[5]Lyell, one of the founding fathers of modern geology, used the captains’ observations as an example of “the formation by natural causes of great lakes.” Lyell stated that … Continue reading A nice descriptive detail recorded only in Clark’s Elkskin-bound journal on October 30th stated:

This part of the river resembles a pond partly dreaned leaving many Stumps bare in & out of the water.

It was late on 30 October 1805, when the expedition encountered the head of the Cascade Rapid complex, called the “Great” or “Grand Shute” by Clark at various times in his October 30 to 1 November 1805, journals and depicted as the “Great Rapid or Shute” on his route map.[6]Moulton, ed., Atlas, 1: Map 78. Clark’s initial observation of “maney large rocks also, in the head of the Shute” was confirmed the next day when he witnessed: “This Great Shute or falls is about ½ a mile with the water of this great river Compressed within the Space of 150 paces in which there is great numbers of both large and Small rocks, water passing with great velocity forming & boiling in a most horriable manner.” Clark then surmised a possible cause for his damming hypothesis.

[31 October 1805:] Several rocks above in the river & 4 large rocks in the head of the Shute; those obstructions together with the high Stones which are continually brakeing loose from the mountain on the Stard Side and roleing down into the Shute aded to those which brake loose from those Islands above and lodge in the Shute, must be the Cause of the rivers daming up to Such a distance above.

Observations on the Way Back

On the return journey, Lewis concisely summarized the relationship that he and Clark had deduced of the damming of the river at the Cascades (what Lewis referred as the “rapids”) and the distribution of “doated” (i.e., decayed) trees in the Columbia River Gorge:

[14 April 1806:] throughout the whole course of this river from the rapids as high as the Chilluckkittequaws, we find the trunks of many large pine trees s[t]anding erect as they grew at present in 30 feet water; they are much doated and none of them vegetating; at the lowest tide of the river many of these trees are in ten feet water.

certain it is that those large pine trees never grew in that position, nor can I account for this phenomenon except it be that the passage of the river through the narrow pass at the rapids has been obstructed by the rocks which have fallen from the hills into that channel within the last 20 years; the appearance of the hills at that place justify this opinion, they appear constantly to be falling in, and the apparent state of the decayed trees would seem to fix the era of their decline about the time mentioned.

These key geologic observations were of sufficient interest for Nicholas Biddle and William Clark to discuss during the time Biddle was preparing the journals for publication circa April 1810. Biddle’s notes for Clark’s 31 October 1805, journal description indicate he was clarifying the overall geomorphic setting at Upper Cascade Rapid:

river widens is gentle & becomes like a pond with trees or stumps on each side where there appear to have been flats[,] on the north Side near the Islands the mountain seems to have been undermined & fallen in upon the islands, thro’ large rocks into the current. On the South Side the mountain comes to the waters edge but has not the same appearance of having fallen in.[7]Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783-1854, Second Edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:540. Per the editorial style in the … Continue reading

There are multiple revealing discoveries in these observations that are worth some detailed analyses, including the cataclysmic event that dammed the river, the life span of the upstream impoundment that formed behind the landslide, the geographic extent where the expedition noted the submerged trees, and the age of those inundated trees, which in turn would provide a date of when the landslide occurred.

Landslip Above the Cascades

Paul Kane (1810–1871)

Watercolor and pencil on paper, 5 3/8 x 9 inches (13.7 x 22.9 cm). Courtesy Stark Museum of Art, bequest of H.J. Lutcher Stark, 1965, collections.starkculturalvenues.org/objects/37952/landslip-above-the-cascades?ctx=a2103a32-7675-4ff5-b402-ddb3c4b7cb61&idx=116.

Bonneville Landslide

Through their observations, Lewis and Clark correctly identified what is now technically referred to as the Bonneville rock slide-debris avalanche, a cataclysmic landslide off the slopes of Table Mountain north of the Columbia River (the north or “Stard.” side). As clarified in the Nicholas Biddle notes, Clark’s geography as recorded in his 1 November 1805, course and distance remarks was descriptively simple but correct, having the “low mountain Slipping in on the Stard Side high on the Lard Side.” Lewis, who noted on 12 April 1806, that “the mountains are high steep and rocky. the rock is principally black,” remarked in his 14 April 1806, journal entry that these hills “appear constantly to be falling in,” and he was generally correct in his assessment. Although geologists believe that the 5.4 square-mile Bonneville landslide of Grande Ronde Basalt[8]See Columbia River Basalts. failed catastrophically, it was discovered to be only the latest in a series of massive rock failures near the Cascades that total nearly 14 square miles; even though these earth movements are thought to have largely stabilized, the landslide complex remains active.[9]O’Connor and Burns, “Cataclysms and Controversy,” 240, 245 and also Wells, et al., “Gorge to the Sea,” 741, who reported that a nearly 40-acre landslide occurred between … Continue reading

As Lewis and Clark surmised, the Bonneville landslide did have a major damming effect on the river channel (in fact, it completely crossed the Columbia River). It created a temporary lake that flooded upstream riverside woodlands, and produced the submerged forest they so diligently noted. There is evidence the landslide originally flooded the Columbia River valley back to Wallula Gap; but following a partial breach of that blockage,[10]The maximum height of the original landslide impoundment has been estimated to have been as high as 300 ft above sea level [asl](about 225 feet higher than 10-year moving average of the Bonneville … Continue reading a longer-lived, smaller lake persistently impounded the river back to The Dalles. When Lewis mentioned the occurrence of trees “throughout the whole course of this river from the rapids as high as the Chilluckkittequaws,” he was referring to a small band of natives the captains associated with the Wishram-Wascos Indians[11]Per Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Lewis and Clark Journals, An American Epic of Discovery (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 277, n. 86. The village was about four miles downstream … Continue reading that were encountered just above Crates Point, about thirty-eight miles upriver of the Upper Cascade rapids.[12]In statute miles, as measured by the author using the NOAA Office of Coast Survey chart no. 18532, Columbia River, Bonneville to The Dalles, found at www.charts.noaa.gov/OnLineViewer/18532.shtml. … Continue reading It is not possible to verify this submerged tree distribution today given the drowning of the Gorge with the closure of the Bonneville Dam in 1938, but prior to the completion of the dam, botanist Donald Lawrence commenced his comprehensive mapping of submerged trees.[13]Lawrence’s principal initial field work was conducted in 1934-1935. He noted that “about 1800 [trees] were visible during the low water of 1934.” Donald B. Lawrence, “The … Continue reading Over the course of his decades-long research, Lawrence documented the distribution of submerged trees from the Cascades all the way back to essentially the same spot Lewis noted,[14]Donald B. Lawrence and Elizabeth G. Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods Legend, Its Origin, History and Dating,” Mazama, 40:13 (December 1958), 33-41, see Figure 4. demonstrating yet again how even the most cursory mention in the Lewis and Clark journals proved to be remarkably accurate.

Radiocarbon Dating

At a time where radiocarbon dating[15]The principle of radiocarbon dating, which utilizes the remains of organic material (e.g., wood), is predicated on the systematic and predictable decay of the unstable carbon-14 isotope (14C) that … Continue reading was emerging as one of the most valuable tools in archaeological and geological research, Lawrence’s initial attempts at dating wood samples from a few submerged stumps yielded radiocarbon dates of 670 years (± 300) before present (BP) and 700 years (± 200) BP essentially placing the occurrence of the landslide between AD 1250 and 1280.[16]Lawrence and Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods,” 41. By international convention, radiocarbon dates are normally given as years before present (years BP), with 1950 as the base year. To independently corroborate the dates obtained from submerged trees, efforts were also made to age-date trees that grew on the landslide debris, under the logical assumption that they had colonized the landslide deposit sometime after it occurred.[17]An early attempt by Donald Lawrence to date trees growing on the landslide using just dendrochronology (tree ring dating) could only indicate that the Bonneville landslide had occurred before AD … Continue reading Radiocarbon dating on some Douglas firs found growing atop the Bonneville landslide suggested it occurred sometime between AD 1400 and the late 1500s.[18]Personal communication, Patrick T. Pringle, Washington Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology, Olympia, Washington, 29 January2003 (Mr. Pringle is now at Centralia College in Washington … Continue reading Advances in correcting and calibrating the radiocarbon method have improved the accuracy of the technique[19]Accuracy is enhanced by applying 13C/12C isotope ratio corrections and adjusting for “true” half-life of 14C (the original Libby half-life of 5,568 years was found to be underestimated by … Continue reading so reanalyses of Lawrence’s surviving original submerged wood samples has been performed. The results indicate the trees died between AD 1425 and 1450,[20]O’Connor and Burns, “Cataclysms and Controversy,” 246. dating the Bonneville landslide to roughly 350 years prior to the expedition’s arrival.

Native American Oral History

All of the evidence gathered by Lewis and Clark, and the subsequent geologic and dendrochronologic research by scientists studying the Bonneville landslide, provides persuasive credibility to early documentation of a Native American oral history that spoke of a natural dam blocking the river. The earliest reliable account of that history was recorded by Daniel Lee, a Methodist missionary who first arrived in western Oregon in September 1834. Exactly when Lee learned of the oral tradition isn’t noted in his 1844 book Ten Years in Oregon, but it was most likely to have been after he established a mission at The Dalles in March 1838.[21]Daniel Lee and Joseph H. Frost, Ten Years in Oregon (New York, New York: J. Collord, 1844), 1-344, see p. 261. There is some indication that Lee spent considerable time among the Cascade peoples in … Continue reading Starting that year, and up until his departure from Oregon in August 1843, Lee made routine round-trip journeys to the Willamette Mission, passing through the Cascades region nearly every trip.[22]The Willamette Mission was located about 40 miles south-southwest from the confluence of the Willamette River with the Columbia before it was moved farther south to present-day Salem in 1840. Lee … Continue reading By his own account, Lee traveled between The Dalles and the Willamette Mission a total of thirty-two times, giving him ample opportunity to become steeped in the Native American history of the river.[23]By deconstructing his narrative history, the author has discerned that Lee traveled past the Cascades seven times in 1840 and eight times in 1842. Lee related:

“The Indians say these falls are not ancient, and that their fathers voyaged without obstruction in their canoes as far as the Dalls. They also assert that the river was dammed up at this place, which caused the waters to rise to a great height far above, and that after cutting a passage through the impeding mass down to its present bed, these rapids [the Cascades] first made their appearance.”[24]Lee and Frost, Ten Years in Oregon, 200. The possibility that Native Americans could walk across the Columbia while the river was completely blocked was later interpreted and transmuted into the … Continue reading

How long it took the Columbia River to fully breach the toe of the Bonneville landslide debris and for the impoundment to completely drain is unknown. As theorized by Donald Lawrence, the impoundment endured long enough to allow tens of feet of silt to bury the lower trunks of the trees,[25]Lawrence, “Submerged Forest,”587-588. which only commenced slowly degrading after the Columbia River had completely breached the toe of the landslide and the river’s rejuvenated flow began to wash the silt away. This sediment entombment preserved the tree stumps far longer than their exposed (and long-lost) upper sections, leading Lawrence to opine: “It is easily understood why some early observers thought the trees had been dead only a hundred years or less.”[26]Lawrence and Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods,” 37. Accordingly, Lewis’s 20-year estimate, although hundreds of years off in terms of dating the timing of the Bonneville landslide or fixing “the era of their decline” of the trees themselves, may be within a few decades of the final draining of the lake and exhumation of the relatively undecayed stumps noted by the captains.

Notes

| ↑1 | John W. Jengo, “After the Deluge: Flood Basalts, Glacial Torrents, and Lewis and Clark’s “Swelling, boiling & whorling” River Route to the Pacific,” Part 2, We Proceeded On, November 2015, Volume 41, No. 4, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol41no4.pdf#page=10. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Although no date or photographer information was affiliated with this photograph in the archives, this image resembles another photograph of the submerged forest held by the Oregon Historical Society that has been attributed to George Weister, circa 1914. |

| ↑3 | When Clark mentioned “Small nitches are formed in the banks below those projecting rocks,” one can refer back to his Elk-skin-bound journal for clarification and see that he was describing the formation of “Small Bays” along the river edges. Per Moulton, Journals, 5:199, the Elkskin-bound journal was kept between 11 September 1805 and 31 December 1803, and contained Clark’s preliminary journal and rough field notes, essentially serving as the first draft for his notebook journal. |

| ↑4 | Discussions of these noteworthy geological observations can be found in, respectively, John W. Jengo, “‘Blue Earth,’ ‘Clift of White’ and ‘Burning Bluffs’: Lewis and Clark’s Extraordinary Mineral Encounters in Northeastern Nebraska,” We Proceeded On, 37:1 (February 2011), 6-18; John W. Jengo, “‘Witness the Specimens of Lava and Pummicestone’: The North Dakota ‘Burnt Hills’ of Lewis and Clark,” We Proceeded On, 39:3 (August 2013), 19-31; and John W. Jengo, “‘high broken and rocky’: Lewis and Clark as Geological Observers,” We Proceeded On, 28:2 (May 2002), 22-27. |

| ↑5 | Lyell, one of the founding fathers of modern geology, used the captains’ observations as an example of “the formation by natural causes of great lakes.” Lyell stated that “Captains Clark and Lewis found a forest of pines standing erect under water in the body of the Columbia River in North America, which they supposed, from the appearance of the trees, to have been only submerged about twenty years.” See Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, Being an Attempt to Explain the Former Changes of the Earth’s Surface, by Reference to Causes Now in Operation, 3 volumes (London: John Murray, Albemarle-Street, 1830-1833), 1:190. |

| ↑6 | Moulton, ed., Atlas, 1: Map 78. |

| ↑7 | Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with Related Documents: 1783-1854, Second Edition (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 2:540. Per the editorial style in the Moulton Journals, emendations or interlineations by Nicholas Biddle in ensuing Lewis and Clark journal quotations are often designated as “NB:” |

| ↑8 | See Columbia River Basalts. |

| ↑9 | O’Connor and Burns, “Cataclysms and Controversy,” 240, 245 and also Wells, et al., “Gorge to the Sea,” 741, who reported that a nearly 40-acre landslide occurred between Table Mountain and Greenleaf Peak in midwinter 2007-2008. |

| ↑10 | The maximum height of the original landslide impoundment has been estimated to have been as high as 300 ft above sea level [asl](about 225 feet higher than 10-year moving average of the Bonneville Dam impoundment elevation) and it was in existence long enough to have sediments be deposited along valley wall tributaries at 260 ft asl. This lake level would have flooded the Columbia River valley back about 165 miles to Wallula Gap, but it appears to have lasted only a few decades. Downstream geological evidence suggests a massive, catastrophic lake breach prior to AD 1479-1482, which was succeeded by a smaller impoundment that flooded the river back to The Dalles. O’Connor and Burns, “Cataclysms and Controversy,” 246-247. |

| ↑11 | Per Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Lewis and Clark Journals, An American Epic of Discovery (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003), 277, n. 86. The village was about four miles downstream of Rock Fort. |

| ↑12 | In statute miles, as measured by the author using the NOAA Office of Coast Survey chart no. 18532, Columbia River, Bonneville to The Dalles, found at www.charts.noaa.gov/OnLineViewer/18532.shtml. Accessed 16 September 2015. |

| ↑13 | Lawrence’s principal initial field work was conducted in 1934-1935. He noted that “about 1800 [trees] were visible during the low water of 1934.” Donald B. Lawrence, “The Submerged Forest of the Columbia River Gorge,” Geographical Review, 26:4 (October 1936), 581–592. |

| ↑14 | Donald B. Lawrence and Elizabeth G. Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods Legend, Its Origin, History and Dating,” Mazama, 40:13 (December 1958), 33-41, see Figure 4. |

| ↑15 | The principle of radiocarbon dating, which utilizes the remains of organic material (e.g., wood), is predicated on the systematic and predictable decay of the unstable carbon-14 isotope (14C) that has been taken up by an organism during its lifetime. Knowing the half-life of 14C (i.e., the time period in which half of the 14C in a specimen will decay) allows an age to be calculated upon counting how much 14C remains in a sample. |

| ↑16 | Lawrence and Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods,” 41. By international convention, radiocarbon dates are normally given as years before present (years BP), with 1950 as the base year. |

| ↑17 | An early attempt by Donald Lawrence to date trees growing on the landslide using just dendrochronology (tree ring dating) could only indicate that the Bonneville landslide had occurred before AD 1562. See Lawrence and Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods,” 40. |

| ↑18 | Personal communication, Patrick T. Pringle, Washington Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology, Olympia, Washington, 29 January2003 (Mr. Pringle is now at Centralia College in Washington State). For a discussion of the age dating of trees recovered from excavations at Bonneville Dam, see Robert L. Schuster and Patrick T. Pringle, “Engineering History and Impacts of the Bonneville Landslide, Columbia River Gorge, Washington-Oregon, USA,” in Jan Rybár, Josef Stemberk, and Peter Wagner, eds., Landslides (The Netherlands: A.A. Balkema Publishers/Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers, 2002), 689-699. |

| ↑19 | Accuracy is enhanced by applying 13C/12C isotope ratio corrections and adjusting for “true” half-life of 14C (the original Libby half-life of 5,568 years was found to be underestimated by approximately 3 percent). Because years BP are not the same as calendar years, dendrochronological calibration curves are utilized to correct for the difference between the radiocarbon dates and real time, a variation that occurred because of natural fluctuations of 14C concentrations through time. |

| ↑20 | O’Connor and Burns, “Cataclysms and Controversy,” 246. |

| ↑21 | Daniel Lee and Joseph H. Frost, Ten Years in Oregon (New York, New York: J. Collord, 1844), 1-344, see p. 261. There is some indication that Lee spent considerable time among the Cascade peoples in the winter of 1839-1840 when he speaks of “labouring among the Indians on the river below, down to the Cascades,” (see p. 186), so his first extended exposure to this oral history may date from that time period. |

| ↑22 | The Willamette Mission was located about 40 miles south-southwest from the confluence of the Willamette River with the Columbia before it was moved farther south to present-day Salem in 1840. Lee made these frequent trips to pick up supplies, attend meetings, and greet the arrival of other missionaries at Astoria. |

| ↑23 | By deconstructing his narrative history, the author has discerned that Lee traveled past the Cascades seven times in 1840 and eight times in 1842. |

| ↑24 | Lee and Frost, Ten Years in Oregon, 200. The possibility that Native Americans could walk across the Columbia while the river was completely blocked was later interpreted and transmuted into the “Bridge of the Gods” legend, although there is no indication in Lee’s account that the Native Americans he interacted with referred to it as such. |

| ↑25 | Lawrence, “Submerged Forest,”587-588. |

| ↑26 | Lawrence and Lawrence, “Bridge of the Gods,” 37. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.