The U.S. Board on Geographic Names (GNIS) declares that “Lou-Lou,” “Loo-Loo,” and “Lo-Lo,” were offically replaced by Lolo.

A National Gazetteer

As steadily increasing numbers of eastern, midwestern and foreign emigrants moved to the American West during the decades immediately following the Civil War, duplications of place names, inconsistencies in spellings, and ambiguous locative attributes in the naming and description of topographic features complicated the work of surveyors and map makers, as well as scientists seeking to locate and evaluate deposits of natural resources. In September 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed Executive Order 28, establishing the United States Board on Geographic Names. It was to consist of representatives from nine federal Departments, bureaus and institutions who had already begun to work together on toponymic problems. Initially, the Board’s basic responsibility was simply to standardize procedures relating to geographic nomenclature and orthography.

Subsequently, Executive Order 399, issued by President Theodore Roosevelt in January 1906, directed that suggestions for new names, or for revisions of old ones, were to be evaluated by the Board before publication, and the Board’s decisions were to be considered final. Later that year, the responsibilities of the Board increased. Executive Order 492 directed that “for the unification and improvement of the scales of maps, of the symbols and conventions used upon them, and of the methods of representing relief, . . . all such projects as are of importance shall be submitted to this board for advice before being undertaken.” The Board on Geographic Names was placed under the Department of the Interior when Public Law 80-242 was enacted by the 80th Congress and signed by President Harry S. Truman in July of 1947.

At the onset of the information age in the 1980s and 90s, the U.S. Geological Survey, in cooperation with the Board on Geographic Names, developed a digital gazetteer or geographic dictionary known as the Geographic Names Information System (GNIS). The GNIS provides “information about physical and cultural geographic features in the United States and associated areas, both current and historical.” As of the summer of 2011 it contained 2,204,989 Federally authorized place-names—plus variant names, if any—and the more or less precise geographic location of each feature.[1]The Geographic Names Information System is described in detail at http://geonames.usgs.gov/domestic/ Of particular relevance to the present topic, in the Main Menu on this page, are the … Continue reading It is important to remember that by definition the GNIS deals with names and their places, so we should not expect to find much of importance relative to the meaning or etymology of any name.

16 Places Named Lolo

Currently the GNIS lists 62 places in the United States that bear the name Lolo. If we omit man-made places such as churches, schools, dams and mines, and limit our search to streams, buttes, mountain peaks and passes (respectively, “summits” and “gaps” in the GNIS lexicon), we are left with 16 geographic places named Lolo in Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and British Columbia.

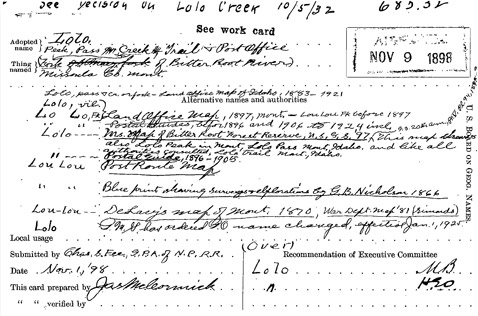

Seven of them occur in a region embracing the creeks of that name in western Montana and north-central Idaho, between the confluence of Montana’s Lolo Creek with the Bitterroot River on the east and the mouth of Idaho’s Lolo Creek at the Clearwater River on the west. There are no listings for “Lou Lou” or “Lo Lo,” etc., in the GNIS. Those versions of the name were repeatedly rejected beginning in 1898, when Lolo was declared the official name (see figure). Searches on any of those variants default to “Lolo.” The “Feature Detail Report” for each entry contains a link to a “Decision Card” in which, if available, some documentation is posted concerning the cartographic history of the place, and (rarely) some facts concerning the feature’s name.[2]On the Web at http://geonames.usgs.gov/domestic/ (accessed March 7, 2011). The purpose of the GNIS is somewhat ambiguous today, inasmuch as it lists not only names of geographic places but also a ski … Continue reading A majority of the links to Decision Cards throughout the GNIS are marked “no data found.”

The BGN at Work

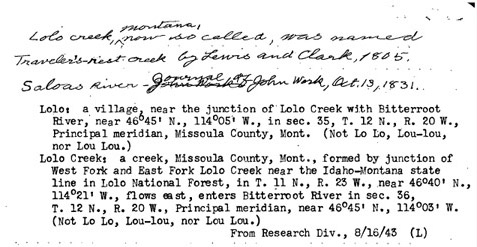

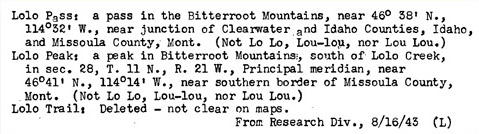

These three Decision Cards illustrate the basic responsibilities of the Board of Geographic Names. The first is the standardization of geographic nomenclature and spelling, which began in earnest in 1898. The first card plus the two handwritten sentences on the second present a rough overview of occurrences of the name Lolo and its familiar variants on maps in the 19th century, and officially concludes that Lolo is the only correct name, and it must displace those variants. The typescript records on cards 2 and 3, dating from 1943, reaffirmed the Board’s decision made 45 years earlier, with four reiterations of “Not Lo Lo, Lou-lou, nor Lou Lou”–perhaps reflecting the persistence of those old variants in common usage, and implicitly discouraging discussion or debate.

Second, the identification of the place associated with each occurrence of the name Lolo is achieved by introducing a “legal description” based on the grid of the Public Land Survey System.[3]A “legal description” is a verbal and numerical description of a given land area using the Public Land Survey System’s grid. The largest unit of land in the PLSS is the Township … Continue reading

Finally, the last entry on page 3 draws attention to the BGN’s insistence on specificity regarding place. The so-called Lolo Trail, for example, was sketched in roughly on a manuscript map dating from 1840, and appeared on printed maps in 1864, 1867 and 1877.[4]1840: Sketch map of the United States between 41 and 51 North Latitude and 90 and 121 West Longitude showing the principal elements of terrain. Manuscript Copy of map by Rev. P. J De Smet; Photo Stat … Continue reading The name was approved by the BGN in 1898, but as work on the trail continued toward the completion of the Lolo Motorway in the 1930s, awareness of the uncertain location of the original Indian paths, by then largely unused for more than 60 years, made it appear prudent by 1943 to delete “Lolo Trail” from the GNIS because its precise location was “not clear on maps.”[5]The Lolo Motorway (Clearwater Forest Road 500) parallels most of the Northern Nez Perce Trail, but is not listed in the GNIS because that gazetteer does not include roads and highways as places. However, after more than 20 years of research, study, and patient ground-truthing, trail historian Steve Russell, has located and precisely mapped virtually all of the original treads.

The place called Lolo Hot Springs, where the Corps of Discovery paused both on its way west (13 September 1805) and its return (30 June 1806), is not included on the above Description Cards because that feature is classified as a populated place. The property and its commercial and recreational developments have been in private ownership since the 1880s.

Lolo in Idaho

The Description of Lolo Creek (Lewis & Clark’s “Collins Creek”), in Clearwater and Idaho Counties, contains the only reference to the Lolo-Lawrence etymology in the GNIS. It reads: “Lolo said to be Indian pronunciation of the name Lawrence, a hunter and trapper who lived among the Flathead Indians. Lolo—peak, pass, creek, p.o., USGB decision, 1898.” The Decision Card is dated June 24, 1932.

Lolo Trail, from Packer Meadow to Weippe Prairie, continues under the same name today, east of Lolo Pass.

There is a Lolo Creek in Benewah County, Idaho, but there is no Decision Card data.

Lolo in Oregon

Lolo Hot Springs, where the Corps of Discovery paused both on its way west (13 September 1805) and its return (30 June 1806), is not included on the above Description Cards because that feature is classified as a populated place. The property and its commercial and recreational developments have been in private ownership since the 1880s.

The only other natural feature in Montana that bears the name Lolo is a small, short (c. 5 miles) stream in Lake County called Lolo Creek. It empties into Flathead Lake about 75 miles due north of the larger and longer Lolo Creek. There is no Description Card in the Feature Detail Report. No evidence has been found that the Lolo-Lawrence etymology has ever been applied to this feature.

There is a Lolo Pass on the ridge marking the boundary between Hood River and Clackamas Counties, less than 20 miles south of the Columbia River. It was said by Stewart to have been “named by the Forest Service from Chinook jargon, ‘carrying, back-packing,’ because supplies had to be packed to it; this same origin is also claimed for the name in ID and MT.”[6]George Stewart, American Place-Names: A Concise and Selective Dictionary for the Continental United States of America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 262. He gave no indication as to what supplies needed to be packed to it, nor why, but that doesn’t matter. The gap is the highest point on the ancient trail across the Cascade Range that for centuries carried commercial traffic between the Indian farms in the Willamette Valley and the fish markets at Celilo Falls.

Methodist missionaries from the Willamette Valley first used the Indian road in 1836 to drive cattle to their new mission at The Dalles. It served as the final leg of the Oregon Trail until 1843, when a few of the earliest emigrants sent their livestock overland by that route while family members portaged their baggage down the rocky riverbank from above Celilo Falls to the foot of the Cascades. By 1846 an alternate way across the Cascades was developed south of Mount Hood by Sam Barlow. Today, much of the older trail over Lolo Pass serves as a corridor for a power line.

In Deschutes County there is a Lolo Butte, but the GNIS entry lacks Decision Card.

Lolo in Washington

There is a Lolo Creek In Clallam County with the variant name, Ida Creek, but but the GNIS has no further information about it.

Lolo in British Columbia

Mount Lolo, on Quadra Island, 220 miles west of Fort Kamloops, was named for Jean-Baptiste Lolo.

Notes

| ↑1 | The Geographic Names Information System is described in detail at http://geonames.usgs.gov/domestic/ Of particular relevance to the present topic, in the Main Menu on this page, are the “Principles, Policies, and Procedures: Domestic Geographic Names,” especially Chapter 3, “Domestic Geographic Names Policies,” Policy VI: Use of diacritical marks; Policy VII: Name duplication; and Policy X: Names of Native American Origin. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On the Web at http://geonames.usgs.gov/domestic/ (accessed March 7, 2011). The purpose of the GNIS is somewhat ambiguous today, inasmuch as it lists not only names of geographic places but also a ski area, a ranger station, two mines, two churches, a medical clinic, and a trailer court, each with “Lolo” as a part of its name. The World Wide Web contains countless new uses of the word Lolo beyond the toponymic functions discussed here, as well as some old ones of extremely obscure meaning and limited use. A page of Wikipedia devoted to the name lists 9 places identified by it (4 in Montana; 1 in Oregon; 2 in British Columbia and 2 in Gabon, Central Africa), plus 13 more-or-less famous people (including a 20th-century Saint), and 4 games. A certain dictionary of slang lists several dozen uses of the word, including two in Hawaiian and one in Philippino. According to www.americansurnames.us/surname/LOLO, Lolo occurs as a surname only 130 times in the U.S. population at large, chiefly in the eastern states from Massachusetts to Florida. Only 5 show up in Idaho; none elsewhere in the Northwest. Most are Caucasian or Hispanic; a few are Black or African-American; fewer still are Asian Pacific, and 14 are of mixed race. None are Native American. As a surname, Lolo ranks 12,254th from most to least common. As of 15 July 2011, in a characteristic frenzy of information overload, “Lolo” brought up “about 42,700,000 results” on the Web. |

| ↑3 | A “legal description” is a verbal and numerical description of a given land area using the Public Land Survey System’s grid. The largest unit of land in the PLSS is the Township (T), which is a square measuring 6 miles on each side, and thus consists of 36 square-mile (640-acre) sections. Townships are numbered consecutively north and south of a Base Line, and are stacked in 6-mile-wide Ranges (R) east and west of a Principal Meridian. Each square-mile section is divisible into quarters of 160 acres each, which may be further divided into quarters of 40 and 10 acres each. The intersection of a state’s Base Line and Principal Meridian marks the Initial Point from which surveys are to be reckoned. The latitude and longitude of the Initial Point is determined by astronomical observations. The PLSS grid may be used to locate a natural feature within 2.5 U.S. survey-acres, which is sufficiently accurate for most general purposes. |

| ↑4 | 1840: Sketch map of the United States between 41 and 51 North Latitude and 90 and 121 West Longitude showing the principal elements of terrain. Manuscript Copy of map by Rev. P. J De Smet; Photo Stat copy from National Archives. 1864: Map of Idaho and Montana and portions of other territories, by Colonel George Thom, A.D.C. & Major of Engineering, for the use of the Head Quarters of the Army (Washington, D.C.: Corp. of Engineers, War Department. 1867: Map of the Territory of Montana to accompany the report of the Surveyor General (Helena, Montana: Surveyor General’s Office). 1877: Map of the Nez Perce Indian campaign (United States Army, Dept. of the Columbia. |

| ↑5 | The Lolo Motorway (Clearwater Forest Road 500) parallels most of the Northern Nez Perce Trail, but is not listed in the GNIS because that gazetteer does not include roads and highways as places. |

| ↑6 | George Stewart, American Place-Names: A Concise and Selective Dictionary for the Continental United States of America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 262. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.