In April 1808, President Thomas Jefferson‘s 12 year-old granddaughter Ellen Randolph wrote to him in Washington detailing a visit that she, her sisters, and some friends had made to see the progress of the building work at Monticello. “I think the hall, with its gravel-colored border is the most beautiful room I ever was in, without excepting the drawing rooms in Washington,” she exclaimed.[1]Ellen Randolph to Jefferson, 14 April 1808, in Edwin Morris Betts and James Adam Bear, Jr., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1966), 341. A year later, in March 1809, when Jefferson retired from the Presidency and went to live full time at Monticello for the first time since 1796, his 40-year building campaign was basically complete. He was finally able to realize, in his new double story Entrance Hall so much admired by his granddaughter, plans for a museum that he had begun to develop in the 1770s.

As visitors to Monticello, and Thomas Jefferson’s own records tell us, his “Indian Hall” in the Entrance Hall eventually housed classical and European art and other gentlemanly grand tour souvenirs, maps of the vicinity and the known world, and skins, bones, and horns of living and extinct North American animals, in addition to some of the objects resulting from the diplomatic, social, and commercial interactions between Lewis and Clark’s exploring party and the indigenous tribes they encountered. The Entrance Hall was the first room visitors entering Monticello would see, and one of its functions as a “public” space of the house seems clear: the western objects contributed to the mélange of goods through which Jefferson demonstrated his encyclopedic interests and placed himself in an international group of educated people who kept abreast of the fine and decorative arts, architecture, natural history and sciences, geography, and ethnography. (Figure 2)

L&C Receipts

The Lewis and Clark objects at Monticello traveled east with the shipment that the explorers dispatched in the barge (called the ‘boat’ or ‘barge’ but never the ‘keelboat’) down the Missouri River from Fort Mandan on 7 April 1805. The shipment, enumerated in an itemized “invoice” or packing list, included ethnographic material, natural history and botanical specimens, minerals, seeds, and five live animals. The invoice and a letter from Lewis arrived in Washington on 13 July.[2]For the invoice, see Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 234-36. For important … Continue reading The four boxes, two large trunks, and three cages took about a month longer, arriving at the President’s House in August while Jefferson was at Monticello. Etienne Lemaire, Jefferson’s maitre d’hotel, wrote him that the shipment had arrived and contained “a kind of cage in which there is a little animal very much resembling the squirrel, and in the other a bird resembling the magpie of Europe.” Having eagerly anticipated the arrival of the shipment for weeks, Jefferson sent Lemaire careful instructions for unpacking and caring for the objects, and urged him to “have particular care taken of the squirrel & [mag]pie . . . that I may see them alive at my return.”[3]Lemaire to Jefferson, 12 August 1805 and Jefferson to Lemaire, 17 August 1805, in Jackson, 253-6.

Distribution

When Jefferson returned to Washington from Monticello in the first days of October 1805 he annotated the packing list, writing the word “came” by the objects that had arrived. Although we do not know the final destination of every object that survived the trip from Fort Mandan to Washington, Jefferson sent material from the shipment to at least three different places. He noted on the packing list and in subsequent letters that he sent a live prairie dog and magpie and some of the animal skins, skeletons, and horns to his friend Charles Willson Peale, the Philadelphia artist and museum impresario, for the Peale Museum. President Jefferson included with Peale’s shipment the seeds and plant, soil, and mineral specimens for the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, the premiere scientific organization in the United States, of which he was also the president.

In his letter to Peale, Jefferson mentioned, “There are some articles which I shall keep for an Indian Hall I am forming at Monticello, e.g. horns, dressed skins, utensils &c.”[4]Jefferson to Charles Willson Peale, 6 October 1805, Jackson, 260-61. On Lewis and Clark objects in the Peale Museum and their ultimate fates see Gilman, 338-40 and McLaughlin, especially 69-81. He sent this third subset of the objects from Lewis and Clark’s shipment to Monticello in March 1806, in one of the regular loads of groceries and building supplies he dispatched from Washington to Virginia. The items from the west are included on a list in Jefferson’s hand documenting this shipment.[5]This document is in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The list details Indian pipes, leggings, bows, arrows, a Mandan pot, an Indian painting, elk horns, deer horns, antelope horns, horns of the mountain sheep, an otter skin, and a weasel skin, along with wine, spices, mustard, chocolate, a bust of Czar Alexander, and prints of Mount Vernon and Niagara Falls. The shipment also contained an Indian map painted on a hide representing the Missouri River and its tributaries between the Platte and the Yellowstone Rivers. Not acquired by Lewis and Clark, the map was presented to President Jefferson in October 1805 on behalf of General James Wilkinson, governor of the Louisiana Territory.[6]Concerning the map, see Jackson, 691-2.

Everything but the map is recognizable from the Fort Mandan packing list, including most notably the painted buffalo hide that Lewis’s list had described as “painted by a Mandan man representing a battle which was fought 8 years since by the Sioux & Ricaras against the Mandans, Minitarras, and Ahwahharways.”

Lost Shipment

Not everything Jefferson intended for the Indian Hall actually made it there. A little more than a year after the 1806 shipment to Monticello, Jefferson wrote to Lewis from Washington that everything in 25 boxes, barrels &c “which I sent round by water” [from Washington to Monticello] that could be damaged by water was. “The others I am told are saved and consequently the horns.” This was presumably part of the material that Lewis personally brought back to Washington. Lewis wrote back three weeks later: “I sincerely regret the loss you sustained in the articles you shipped for Richmond; it seems peculiarly unfortunate that those at least, which had passed the continent of America and after their exposure to so many casualties and wrisks should have met such destiny in their passage through a small portion only of the Chesapeak.”[7]Jefferson to Lewis, 4 June 1807, Jackson, 415 and Lewis to Jefferson, 27 June 1807, Jackson, 418.

Lewis’s Visit

When Lewis returned east in the fall of 1806, his party included Sheheke (Big White), the principal chief of the lower Mandan village (see Sheheke’s Delegation). Jefferson wrote to Lewis in St. Louis in October, knowing that he was planning a trip to visit his mother in Albemarle County, “Perhaps while in our neighborhood, it may be gratifying to him, & not otherwise to yourself to take a ride to Monticello and see in what manner I have arranged the tokens of friendship I have received from his country particularly as well as from other Indian friends: that I am in fact preparing a kind of Indian hall.”[8]Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, 26 October 1806 in Jackson, 350-51. His reference to the native American objects as “tokens of friendship” suggests that 25 years after his visit with Jean Baptiste du Coigne, Jefferson still understood his Indian collection as a set of diplomatic gifts. Although Lewis was in Charlottesville from 13 December until probably just after Christmas, there is no evidence that Sheheke himself actually made the journey to Charlottesville or Monticello.

Visitor Impressions

The Indian Hall made a strong impression on Jefferson’s visitors and is described in numerous first-hand accounts. Visitors used words like “curious,” and “singular,” to articulate the experience of being in the room. Monticello guests were particularly struck by the variety of objects in the room, but in every case singled out North American objects for particular mention, whether because they were the most unfamiliar or because of their predominance in the space.

For example, Auguste Levasseur, secretary to the Marquis de Lafayette on his second visit to America in 1824, wrote: “But what especially excites the curiosity of visitors is the rich museum situated at the entrance of the house. This extensive and excellent collection consists of offensive and defensive arms, dresses, ornaments and utensils of different savage tribes of North America.” Bostonian George Ticknor catalogued the “strange furniture” of the four walls of the room after his visit in 1815, listing heads and horns, “curiosities which Lewis and Clark found on their wild and perilous expedition,” mastodon bones, and the two Native American painted hides. Ticknor noted in his account of the Monticello dinner conversation, “[Mr. Jefferson] seems . . . fond of American antiquities and especially the antiquities of his native state, and talks of them with freedom, and, I suppose, accuracy.” Jefferson expressed his own awareness of the importance of the American aspects of his collection and of the debt he owed to Lewis and Clark, writing to William Clark in 1809, “Your donations and Governor Lewis’ have given to my collection of Indian curiosities an importance much beyond what I had ever counted on.”[9]Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825: Or, Journal of a Voyage to the United States, trans. John Davidson Godman (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1829), 215. For Ticknor’s account … Continue reading

Lieutenant Francis Hall, a British army officer who admired Jefferson and the American government and who visited in 1816, also remarked upon the Americanness of Jefferson’s display, overlooking the plentiful examples of European high culture and grand tour souvenirs. He observed: “the saloon, or central hall, is ornamented with several pieces of antique sculpture, Indian arms, mammoth bones, and other curiosities collected from various parts of the Union.”[10]Entry for 19 October 1831, published in Anne Fontaine Maury, ed. Intimate Virginiana: A Century of Maury Travels by Land and Sea (Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 1941) 187. I am most grateful to Cinder … Continue reading

Preserving Legacies

All of these comments highlight another of Jefferson’s central ambitions for the Entrance Hall, and one that has not heretofore been considered a particularly Jeffersonian motivation: it was a tangible exhibition of his greatest accomplishments as president. In his grand double-story space with his requisite antique sculpture, northern and southern European paintings of the previous few centuries, Houdon busts of contemporary French notables, maps of all the known continents, and a cork model of the pyramid of Cheops, Jefferson demonstrated that he was a global player in the worlds of architecture, aesthetics, history, philosophy, and economics. But by displaying evidence of the human and animal inhabitants of western North America, Jefferson provided his visitors, family, slaves and himself an additional lesson in North American natural history and ethnography. Everyone who entered the house was not only conscious of his curious mind and his participation in international intellectual circles, but understood that he had set in motion a survey to discover the extent, inhabitants, and resources of this new country he helped create, and doubled its size for a bargain-basement price.

From well before his first publication of Notes on the State of Virginia in Paris in 1785, Jefferson had set himself the task of disproving the theories of European naturalists, notably Georges Buffon, that the native people, animals and plants of North America were weaker than and inferior to those of Europe. The meanings and use of the new Entrance Hall solidified as Jefferson finished the house at Monticello in anticipation of his retirement. In the Indian Hall he got his chance to hold the products of the New World up to those of the Old. In the form of elk and moose antlers, big horn sheep, mastodon bones, and particularly the objects made by native peoples, Jefferson’s Indian Hall represented a new kind of cabinet. It was not a space where visitors were merely expected to gape at heaped up goods or marvel at wonders wrought by nature or human dexterity.

Instead, the visual complexity of this room highlighted several core issues in Jefferson’s America. It seems clear that he recognized the centrality of visual knowledge (including cultural, commercial, and scientific) to the expansion of the fledgling republic. Jefferson had believed since the 1780s that a U.S.-sponsored expedition would, in addition to collecting information about who and what was out there, assert American rights to trade in, settle, and govern the vast unknown territory. The personal care he took to plan the Lewis and Clark expedition, to have Lewis trained in the practices of specimen collection and preservation, and to house the expedition’s material fruits in the Peale Museum and the American Philosophical Society, the premier institutions qualified to handle them, as well as his attempts to publish the expedition’s findings in a timely manner, reveal how deeply he was invested in the project. By integrating North American objects within a group of Old World collectibles at Monticello, Jefferson was signaling their significance as well as his own achievements as president, scientist, and collector. Then, as now, his visitors seem to have gotten the message.

University Years

When Jefferson died on 4 July 1826, he left his family $107,000 in debt. Despite Jefferson’s confidence that his executors would organize a lottery to raise the money to allow his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph and her large family to remain at Monticello, there was insufficient public interest in the scheme. Six months later the family was forced to sell the household contents and farm equipment, and all but five of the approximately 200 slaves. Family members had to buy the household items they wanted to keep. The family eventually found a buyer for the house and land in 1831.[11]Peterson, 74-79.

The year before he died, Jefferson wrote a letter to William Clark in which he clearly signaled his intention to give his Entrance Hall collection to the University of Virginia, the foundation of which he referred to as the “hobby of his old age.” He wrote Clark to solicit donations for a museum he planned for the University:

Among other objects of our instn [institution] is the collection of a Museum of Nat. hist. of Minerals, & of curiosities in general of art or nature. Those of Indian arts stand very near to nature itself. Your situation is so [favorable] for assisting us in this collection that I cannot help solliciting your attention to us. . . . We would not trouble you for bulky and heavy articles, which might be too cumbersome and expensive in carriage. Nor yet such as are liable to be destroyed by worms, moisture etc. but for chrystals minerals small Indian worthy and other curiosities which might be easily transported and preserved. Perhaps you may have in your own collection have duplicates of some things of which you could spare one, or things too common to be curious there, but rare and curious here. In short you know our country so well as to be at no loss to distinguish what would be acceptable here. I give to the Univ. the whole of my collections which is considerable and much indeed of which was furnished me from the expedn. of yourself & Govr. Lewis to the Pacific.[12]For Monticello after Jefferson, see Mark Leepson, Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built (New York: Free Press, 2001).

Despite Jefferson’s statement of his intentions in this letter, it is unclear exactly which portions of his collection of Native American material and natural history specimens ended up at the University and what ultimately happened to most of them, nor does it seem that Clark ever donated any objects. In October 1826, according to the records of the meetings of the Visitors (trustees) of the University of Virginia, a room on the first floor of the Rotunda “was to be finished and fitted for the reception of the natural and artificial curiosities given to the University by the late venerable Rector [Jefferson]; and to have them there suitably arranged for preservation and exhibition.”[13]Jefferson to William Clark, 12 September 1825, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Surprisingly, exhaustive searches at the University over many years have not turned up any records cataloguing Jefferson’s “natural and artificial curiosities.”

The minutes of the meetings of the Visitors mention frequent relocation of the collection between 1828 and 1848, suggesting that it was several times forced to give way to the growing spatial needs of the Professors of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry. In 1828 the objects were moved from the first floor of the Rotunda to the basement to make room for scientific apparatus; the next year they moved to the upper gallery.[14]University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 2 October 1826. In 1830 the Visitors approved the creation of a Museum in the basement story. In 1831 Franklin Peale, one of the sons of Charles Willson Peale who ran the Peale Museum after his father’s death, traveled to Charlottesville to organize and arrange “the collection known under the denomination of Mr. Jefferson’s donation.”[15]University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 3 October 1828. In the same year a young woman named Ann Maury recorded in her diary that she visited the University and saw the lecture rooms and library in the Rotunda. She reported seeing “some of Mr. Jefferson’s collections of curiosities, Indian utensils & dresses & weapons & a part of a mammoth’s skeleton.”

This is the only known account written by someone who saw Jefferson’s Indian collections at the University.[16]University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors , 21 July 1830; 20 July 1831.

Brooks Museum

Thirty years later, in June 1878, the Lewis Brooks Museum of Natural Science opened its doors on the University of Virginia grounds (Figure 5); it was a free-standing museum of natural history, given to the University by Lewis Brooks of Rochester, New York. A student publication, the Virginia University Magazine, had reported in 1876 that geological “specimens of Mr. Jefferson’s own accumulation” would be incorporated into the new collections that had been purchased for the Brooks Museum.[17]University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 7 July 1840; 5 July 1841; 28 June 1848. It is certain that natural history specimens from Monticello’s Entrance Hall, most notably the Lewis and Clark elk antlers, moose antlers acquired by Jefferson in 1784, and mastodon bones excavated by William Clark in Kentucky following the expedition, also found a home in the Brooks Museum.[18]See Jeffrey L. Hantman, “Brooks Hall at the University of Virginia: Unravelling the Mystery,” The Magazine of Albemarle County 47 (1989): 62-92 It remains unclear whether any Native American objects from Jefferson’s Lewis and Clark collection were ever in the Brooks Museum.

The Brooks Museum was dismantled in the late 1940s, and its collections dispersed to various University departments or placed in storage. At the time of the dispersal, Jefferson’s collection seems to have no longer survived as a recognizable entity. The Lewis and Clark elk antlers and Jefferson’s moose antlers were loaned back to Monticello by the Biology department in 1949 and the mastodon bones by the Geology department in 1960. All of these objects remain on long-term loan to Monticello. The elk antlers (Figure 6) are thus the only original Lewis and Clark objects from Jefferson’s collection to survive at Monticello today and have an amazingly complete provenance that renders them traceable from Fort Mandan to Washington, Monticello, the University of Virginia, and back to Monticello. No Native American objects acquired by Lewis and Clark have ever been located at the University, despite extensive searching.

Recreating Indian Hall

Beginning in early 2000, in preparation for the bicentennial of the Lewis and Clark expedition, curators at Monticello (owned and operated as an historic site by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation since 1923) launched an effort to bring the Entrance Hall at Monticello more closely in keeping with visitor descriptions of the space during Jefferson’s lifetime. At the time, the Entrance Hall featured reproductions of Native American objects from the collection of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, installed in 1996.

The misperception that items currently in the Peabody had belonged to Jefferson and been in his Indian Hall at Monticello dates to the late 1970s and an erroneous assumption made by Julian Boyd, editor of the Papers of Thomas Jefferson. Boyd surmised that since a member of the family who acquired Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest estate after Jefferson’s death in 1826 had donated early 19th-century Native American material to the Peale Museum, the material, which eventually made its way into the Peabody Museum, must have been Lewis and Clark material from Jefferson’s Indian Hall.[19]Virginia University Magazine 14: 9 (June 1876): 495.

Beginning the later 1990s, Dr. Castle McLaughlin, Curator of North American Ethnography at the Peabody, unraveled the story. McLaughlin determined that Lieutenant George Christian Hutter, whose father Colonel Christian Jacob Hutter donated about 30 objects to the Peale Museum in 1828, probably collected them from tribes along the Missouri River while he served on the Atkinson-O’Fallon Expedition in 1825 and 1826. The younger Hutter was married to William Clark’s wife’s niece and knew Clark in St. Louis, which gave him another possible means of acquiring Native American materials. It was not until 1840 that Hutter’s half-brother married into the family that purchased Poplar Forest from Jefferson’s grandson Francis Eppes.[20]The problem with Boyd’s assumption is that the Hutter family did not acquire Poplar Forest until 1840, 12 years after the objects had been donated to the Peale Museum. This error was disseminated … Continue reading McLaughlin’s research proves that the objects the Hutter family gave to the Peale Museum in 1828, whether they were personally collected by Lieutenant G. C. Hutter or acquired by him from William Clark, were never Thomas Jefferson’s and never at Monticello.[21]McLaughlin, chapters 6-7.

Curators at Monticello made the decision to remove the reproductions of the Peabody objects from the Entrance Hall and to install objects relating to the period in which Lewis and Clark were collecting from the tribes along the Missouri the objects they sent to Jefferson. A panel of experts, including Castle McLaughlin of the Peabody Museum and Native American curators and scholars, recommended that since Jefferson’s original objects could not be located and that original items from the 1803-06 period were extremely rare, fragile and therefore difficult to borrow and exhibit, that Monticello consider commissioning “new” reproductions from native American artists from upper Missouri tribes who were preserving traditional methods and using traditional materials. George Horse Capture of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian recommended further that the project involve professional development opportunities for young native American artists. Working with Butch Thunder Hawk, a Hunkpapa Lakota artist and tribal arts teacher who was already a consultant to the Peabody, the Peabody-Monticello Native Arts project was launched.

Thunder Hawk teaches at United Tribes Technical College in Bismarck, ND. In the summer of 2001, Thunder Hawk and his colleague Wayne Pruse ran a summer school in which students in the tribal arts program under Thunder Hawk’s supervision made a group of arrows, clubs, shields, and pipes. In addition, hide painter Dennis Fox (Mandan-Hidatsa) and quill worker Jo Esther Parshall (Cheyenne River Lakota) were commissioned to make the painted battle robe and the painted map and quilled leggings and moccasins. The resulting works are not exact replicas of surviving originals. Instead, the artist studied objects in the Peabody’s collection and created new ones using accurate techniques and materials while incorporating their own interpretations. The resulting display in Monticello’s Entrance Hall presents material that is authentic, just not old. (Figure 7)

Curiosity Cabinets

Jefferson’s desire to include a museum among the spaces at Monticello, as well as the genesis of his collection of Native American objects, long predated the Lewis and Clark Expedition, but it is clear that the material fruits of the Expedition were central to his establishment of the “Indian Hall” in Monticello’s Entrance Hall. In his endeavor of gathering together and displaying objects representing a range of human enterprise and knowledge, Jefferson was in good company, both historically and intellectually.

A curiosity cabinet in the early modern period was an assemblage of a wide array of items expressing the multiple, even universal, interests of the collector, particularly in the marvelous. They included what we today consider works of art, but also rare and precious or bizarre specimens from the natural world, scientific instruments, ethnographic material, and elaborately or amazingly wrought items such as turned ivory, engraved gems, or nautilus shells transformed into drinking cups. These cabinets derived from the Renaissance belief that universal knowledge was attainable and that by gathering together personally chosen objects from the natural and artificial worlds, the collector could gain insight into God’s universe. When visited, seen, and discussed by peers, social superiors, or competitors, collections provided their owners with a high degree of cultural capital. Setting the owner apart as an individual of learning, intellect, distinction, and discrimination, with the financial means to obtain the objects, the collection could even suggest the individual’s ability to control or contain the world, represented by the wide range of items in the collection, or at least to occupy a privileged place in the cosmos.[22]On the curiosity cabinet see Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, eds. The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in 16th and 17th Century Europe (Oxford, 1985) and Joy Kenseth, ed. The Age of … Continue reading

Monticello’s Evolution

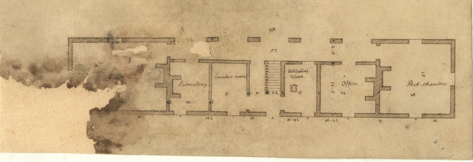

Figure 6

Unrealized plan for a Monticello outbuilding containing his private apartment, Thomas Jefferson, 1768-1770.

To see labels, point to the image.

Thomas Jefferson Coolidge Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society. Monticello: dependencies (study plans), recto, 1768-1770,

by Thomas Jefferson. N30; Ki [electronic edition]. Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003. http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org.

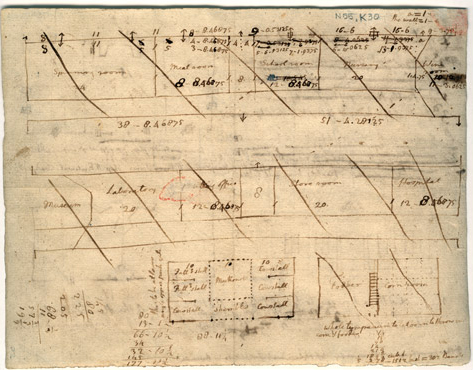

Figure 7

Unrealized plans for Monticello dependency wing, Thomas Jefferson, 1771 or 1772.

To see labels, point to the image.

Thomas Jefferson Coolidge Collection, Massachusetts Historical Society. Monticello: dependencies (study plans), verso, 1771 or 1772, by Thomas Jefferson. N55; K30 [electronic edition]. Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003. http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org.

The evolution of Jefferson’s ideas for a museum at Monticello may be traced through the hundreds of architectural drawings he made during the 40-year development of the house. Not surprisingly, the drawings make clear that from his earliest planning stages he intended to include in his house spaces for study, reflection, and scientific endeavors; the early drawings locate these spaces in his private apartment. These are the kinds of domestic spaces that evolved into rooms for displaying and discussing collections, and eventually into museums in the modern sense of the word.

In a drawing depicting an early, unrealized idea for an outbuilding containing his private apartment (N-30) (Figure 6), Jefferson included a space labeled “laboratory” in addition to his bedchamber, office, a privy, and a lumber room. In a sketch likely made about 1777 or 1778 in which he experimented with ideas for room functions for the as-yet unbuilt dependency wings (work spaces) of the first Monticello (N-55) (Fig. 4), Jefferson included a bowed space labeled “Museum” next to one labeled “Laboratory.”[23]Fiske Kimball considered this drawing, which he dated to 1771 or 1772, to be a first sketch for the dependencies of the first Monticello, and analyzed it together with Jefferson’s drawing of the … Continue reading The word “laboratory” at that time, as now, meant a space or building for conducting investigations in the natural sciences. Originally denoting a temple to the Muses, the word “museum” referred at Jefferson’s time to a scholar’s study or to a building or part of a building dedicated to the pursuit of learning or the arts, and could also refer to a building or institution where objects were preserved and exhibited.

In the second Monticello, as it neared completion during the Lewis and Clark Expedition and at the time of the establishment of the “Indian Hall,” Jefferson’s personal apartment did not contain storage or display space for objects other than books, scientific instruments, and garden seeds, but did have ample space for reading, drafting, and scientific investigation.[24]Jefferson leveled the top of Monticello mountain and began constructing his house in 1769 at the age of 26. The house was largely complete by the time he left to become trade minister, and later … Continue reading Jefferson ultimately located the museum in the Entrance Hall and, in keeping with contemporary uses of the term, also used the word “cabinet” to refer to this room filled with his wide-ranging collections.[25]For example, in a letter to Caspar Wistar of 19 December 1807, Jefferson writes, “There is a tusk and a femur which Gen. Clark procured particularly at my request for a special kind of Cabinet … Continue reading

In contrast to their prominence in the second Monticello, we do not know how, where, or even if Jefferson displayed his collections in his house prior to the completion of the Entrance Hall in 1808. He began acquiring Native American objects by at least 1781, when as governor of Virginia he was presented some painted animal skins by Jean Baptiste du Coigne, a visiting chief of the Kaskaskia tribe of the Illinois confederacy. Jefferson’s speech to du Coigne is preserved and includes his official reaction to receiving these diplomatic gifts; this suggests that he may have displayed painted skins in the first Monticello as he was to do in the second. Jefferson told du Coigne: “I have carefully attended to the figures represented on the skins, and to their explanation, and shall always keep them hanging on the walls in remembrance of you and your nation. I have joined with you sincerely in smoking the pipe of peace; it is a good old custom handed down by your ancestors, and as such I respect and join it with reverence.”[26]Speech to Jean Baptiste Du Coigne, June 1781, in Julian Boyd, ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 6:60. In Jefferson and the Indians: The Tragic Fate of the First Americans (Cambridge and London: … Continue reading

The rhetorical formula of Jefferson’s address to du Coigne suggests that he was at least cognizant of the significance within Native American culture of both ritual smoking and gift-giving. Reciprocal gift exchange was a central element of Indian-white diplomacy on the American frontier, which in 1781 was located in the Northwest Territory, roughly the present-day states of Illinois, Ohio, and Indiana. Diplomatic gift giving was a major channel through which Native American objects from the Northwest territory and further west arrived on the east coast and entered early museum collection, such as Pierre-Eugene du Simitière’s American Museum in Philadelphia, open from 1782 until 1785, the Peale Museum, established in 1786, and the Tammany Society’s American Museum in New York, established in 1790 and run by Gardiner Baker.[27]For an overview of these early museums see Joel J. Orosz, Curators and Culture: The Museum Movement in America, 1740-1870(Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990).

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Plan a trip related to Jefferson’s Indian Hall:

Notes

| ↑1 | Ellen Randolph to Jefferson, 14 April 1808, in Edwin Morris Betts and James Adam Bear, Jr., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1966), 341. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For the invoice, see Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 234-36. For important discussions of the material culture of the expedition and the whereabouts of surviving objects, see Carolyn Gilman, Lewis and Clark: Across the Divide (Washington and London: Smithsonian Books, 2003), especially 335-53, and Castle McLaughlin, Objects of Diplomacy: Lewis & Clark’s Indian Collection (Seattle and London, University of Washington Press, 2003). |

| ↑3 | Lemaire to Jefferson, 12 August 1805 and Jefferson to Lemaire, 17 August 1805, in Jackson, 253-6. |

| ↑4 | Jefferson to Charles Willson Peale, 6 October 1805, Jackson, 260-61. On Lewis and Clark objects in the Peale Museum and their ultimate fates see Gilman, 338-40 and McLaughlin, especially 69-81. |

| ↑5 | This document is in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. |

| ↑6 | Concerning the map, see Jackson, 691-2. |

| ↑7 | Jefferson to Lewis, 4 June 1807, Jackson, 415 and Lewis to Jefferson, 27 June 1807, Jackson, 418. |

| ↑8 | Jefferson to Meriwether Lewis, 26 October 1806 in Jackson, 350-51. |

| ↑9 | Auguste Levasseur, Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825: Or, Journal of a Voyage to the United States, trans. John Davidson Godman (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea, 1829), 215. For Ticknor’s account see Merrill D. Peterson, ed. Visitors to Monticello(Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1989), 61-66. Jefferson to William Clark, 10 September 1809, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. |

| ↑10 | Entry for 19 October 1831, published in Anne Fontaine Maury, ed. Intimate Virginiana: A Century of Maury Travels by Land and Sea (Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 1941) 187. I am most grateful to Cinder Stanton for this reference. |

| ↑11 | Peterson, 74-79. |

| ↑12 | For Monticello after Jefferson, see Mark Leepson, Saving Monticello: The Levy Family’s Epic Quest to Rescue the House that Jefferson Built (New York: Free Press, 2001). |

| ↑13 | Jefferson to William Clark, 12 September 1825, Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. |

| ↑14 | University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 2 October 1826. |

| ↑15 | University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 3 October 1828. |

| ↑16 | University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors , 21 July 1830; 20 July 1831. |

| ↑17 | University of Virginia, Minutes of the Board of Visitors, 7 July 1840; 5 July 1841; 28 June 1848. |

| ↑18 | See Jeffrey L. Hantman, “Brooks Hall at the University of Virginia: Unravelling the Mystery,” The Magazine of Albemarle County 47 (1989): 62-92 |

| ↑19 | Virginia University Magazine 14: 9 (June 1876): 495. |

| ↑20 | The problem with Boyd’s assumption is that the Hutter family did not acquire Poplar Forest until 1840, 12 years after the objects had been donated to the Peale Museum. This error was disseminated by Charles Coleman Sellers in his 1980 book Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art (New York: W. W. Norton) and elsewhere. |

| ↑21 | McLaughlin, chapters 6-7. |

| ↑22 | On the curiosity cabinet see Oliver Impey and Arthur MacGregor, eds. The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in 16th and 17th Century Europe (Oxford, 1985) and Joy Kenseth, ed. The Age of the Marvelous (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, 1991). |

| ↑23 | Fiske Kimball considered this drawing, which he dated to 1771 or 1772, to be a first sketch for the dependencies of the first Monticello, and analyzed it together with Jefferson’s drawing of the first floor plan of the house that contains bowed rooms at either end,Thomas Jefferson, Architect (Boston, 1916). Frederick Doveton Nichols also dated the drawing 1771 or 1772 and considered it a first study for the dependencies, Thomas Jefferson’s Architectural Drawings, (Charlottesville: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, 1961, 35.). William L. Beiswanger, Robert H. Smith Director of Restoration at Monticello, believes that even though the advent of Jefferson’s idea for linking the dependencies to the main house dates from around 1772, this drawing dates about 1777 or 1778 due to the presence of the bow rooms, which research since Nichol’s work was published suggests were added to the wings of the house about that time. For discussion of the design of the original Monticello, see Gene Waddell, “The First Monticello,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 46:1 (March 1987) 5-29. I am grateful to Bill Beiswanger for sharing with me his unparalleled knowledge of Jefferson’s architectural drawings and for discussion of these early drawings, their chronology, and implications. |

| ↑24 | Jefferson leveled the top of Monticello mountain and began constructing his house in 1769 at the age of 26. The house was largely complete by the time he left to become trade minister, and later minister plenipotentiary, in Paris in 1784. In 1796, seven years after his return, Jefferson began significant renovations, completed by his retirement from the presidency in 1809, resulting in a different house. The early and later versions of the house are known as Monticello I and Monticello II. |

| ↑25 | For example, in a letter to Caspar Wistar of 19 December 1807, Jefferson writes, “There is a tusk and a femur which Gen. Clark procured particularly at my request for a special kind of Cabinet I have at Monticello.” Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. |

| ↑26 | Speech to Jean Baptiste Du Coigne, June 1781, in Julian Boyd, ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 6:60. In Jefferson and the Indians: The Tragic Fate of the First Americans (Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1999), 104, Anthony F. C. Wallace has conflated the later painted hides from the Lewis and Clark period known to have been at Monticello in the years following the Expedition with the earlier gifts from Du Coigne. |

| ↑27 | For an overview of these early museums see Joel J. Orosz, Curators and Culture: The Museum Movement in America, 1740-1870(Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990). |