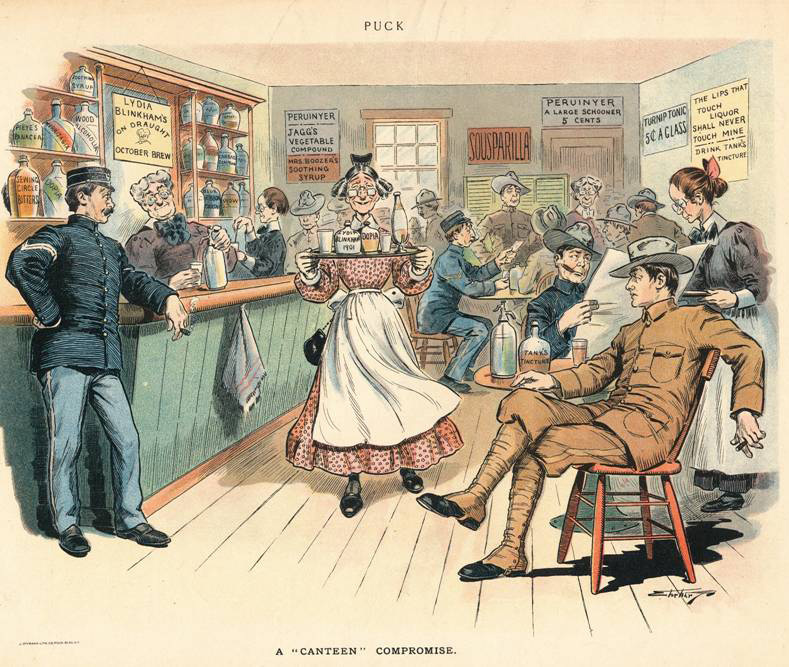

A “Canteen” Compromise

Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound

From Puck (magazine) 59, no. 1520 (18 April 1906), books.google.com/books?id=4etCAQAAIAAJ&lpg=PP250&pg=PP250#v=onepage.

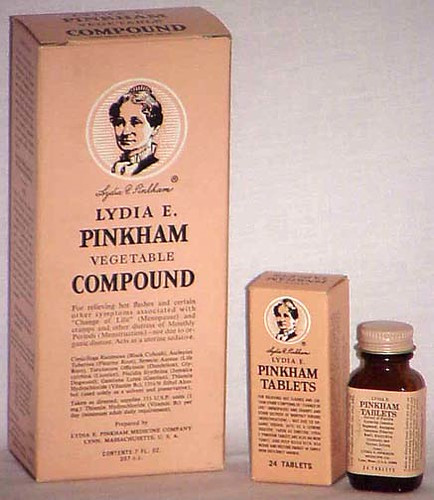

Lydia Pinkham (born 1819) marketed her patented medicine as a “natural” alternative to the purgative treatments of the Enlightenment Era which were often made from calomel. The elixir was made mostly of alcohol with a sprinkling of herbs explaining the satire in the above lampoon. In 1915, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) took action against the company.

Lydia E. Pinkham Vegetable Compound and Tablets

Provided by the Federal Drug Administration, www.flickr.com/photos/fdaphotos/33856349432/.

Anti Calomel was not just an anthem. It was a reflection of the end of the Enlightenment and the start of “genteel tradition.”

The spirit and ideals of 18th-century Enlightenment by which Thomas Jefferson and his circle had lived, and with which Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had been imbued, weakened sharply after the War of 1812, and were ancient history by the late 1820s. The election of Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), “the voice of the people,” to the Presidency of the United States in 1828, chiefly with the support of western farmers and eastern laborers, inaugurated an “era of good feelings” in which the worth and ambition—and the tastes—of the common man were elevated to the status of essential Americanism. Within less than a decade, sales of western land reached 10 million acres. With the abolishment of property ownership as a qualification for the right to vote, the old plantation aristocracy permanently lost its hold on American destiny. Nicholas Biddle, who had tossed off his paraphrase of Lewis and Clark’s journals as a service to the nation, then turned his energies and talents toward the administration of the Second National Bank, was drummed out of his position of national fiscal leadership, and the doors of “Biddle’s Bank” were slammed shut with the self-righteous passion of Jacksonian democracy.

With the sudden redistribution of national wealth, the population base of daring business entrepreneurs broadened, its educated and “cultured” leaders and their wives—especially their wives—established themselves like a veneer on American upper-class society. Aesthetically of that era grew into an incipient middle-classism, which sublimated itself into what it eagerly and proudly dubbed “the genteel tradition.” The 20th-century music historian Gilbert Chase shone a spotlight on the genteel tradition’s values: “the cult of the fashionable, the worship of the conventional, the emulation of the elegant, the cultivation of the trite and artificial, the indulgence of sentimentality, and the predominance of superficiality.”

The standard-bearers of the genteel tradition, musically speaking, were the Singing Hutchinsons, a musically talented family from New Hampshire, who came to represent what Gilbert Chase termed the ‘left wing’ of the genteel tradition, approaching the popular tradition while retaining the prestige of elegance and refinement associated with . . . urban culture acquired in Boston and New York.” Fashionable urban audiences sang hymns and sentimental, melodramatic songs, and righteous protest songs such as the mocking “King Alcohol,” “The Gambler’s Wife,” their own insipidly inspirational setting of Longfellow’s “Excelsior,” and the rollicking “Anti Calomel.” Ironically, their theme song, “The Old Granite State,” celebrating the sentimental appeal of rural life, represented the inverse of the Southern Revival movement that had dominated the decade of the Lewis and Clark expedition.

One of the Hutchinson Family’s greatest hits was their celebrated “protest” song “Anti Calomel” which parodied the persistent reliance of doctors on the old mercury-laden nostrum. The song was sung to the tune Ein Fest Burg.

Go Call the Doctor, & Be Quick!

or Anti Calomel

Sung at the Concerts of the Hutchinson Family

Lyrics by J. J. Hutchinson

and Respectfully dedicated to Dr. W. Beach[1]Dr. W. Beach (1794-1868), an herbalist, was already well-known as the author of a popular handbook, The American Practice of Medicine (1833), in which he preached a “reformed system of medicine … Continue reading

1843

Physicians of the highest rank,

To pay their fees would need a bank,

Combine all wisdom, art and skill,

Science and sense, in Calomel.When Mr. A or B is sick

Go call the doctor and be quick

The doctor comes with much good will

But ne’er forgets his Calomel.He takes the patient by the hand,

And compliments him as his friend;

He sits awhile his pulse to feel,

And then takes out his Calomel.He then turns to the patients wife,

Have you clean paper spoon and knife,

I think your husband would do well,

To take a dose of Calomel.He then deals out the precioius grain.

This ma’am I’m sure will ease his pain.

Once in three hours at toll of bell,

Give him a dose of Calomel.The man grows worse quite fast indeed.

Go call the doctor; ride with speed!

The doctor comes, like post with mail,

Doubling his dose of Calomel.The man in death begins to groan,

The fatal job for him is done,

He dies alas, but sure to tell,

A sacrifice to Calomel.And when I must resign my breath,

Pray let me die a natural death,

And bid the world a long farewell,

Without one dose of Calomel.

Notes

| ↑1 | Dr. W. Beach (1794-1868), an herbalist, was already well-known as the author of a popular handbook, The American Practice of Medicine (1833), in which he preached a “reformed system of medicine on vegetable or botanic principles.” |

|---|

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.