James Wilkinson (1757-1825) was one of the most duplicitous, avaricious, and altogether corrupt figures in the early history of the United States. Although he served in the Revolutionary War as adjutant general under General Horatio Gates, he took an oath of allegiance to Spain in 1787, and was paid by the Spanish government as agent Number Thirteen. In 1803, he was appointed governor of Louisiana Territory above the 33rd parallel—the northern boundary of the present state of Louisiana.

—Joseph A. Mussulman[1]The remainder of this article is an extract from We Proceeded On the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation: Arlen J. Large, “Lewis and Clark Under Cover”, We … Continue reading

Selling Out to Spain

Orders have been given to the president’s private secretary and the infantry Captain Lewis to ascend the Missouri River with a military command, and supplied with the articles necessary to make the proper observations at different points, and if circumstances favor the extension of the enterprise, they are to proceed as far as the Pacific Ocean … An express ought immediately to be sent to the governor of Santa Fe, and another to the captain-general of Chihuaga [i.e., Chihuahua], in order that they may detach a sufficient body of chasseurs to intercept Captain Lewis and his party, who are on the Missouri River, and force them to retire or take them prisoners.

—Vincent Folch, the Spanish governor of West Florida[2]Robertson, James A., ed., Louisiana Under the Rule of Spain, France, and the United States 1785-1807 (Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, 1969 reprint of 1910-11 edition), 2:334, 338, 342. Robertson … Continue reading

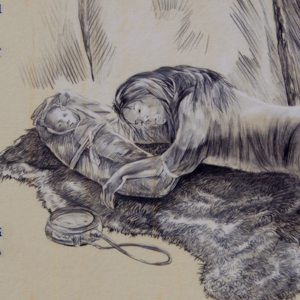

James Wilkinson (1796-97)

Independence National Historical Park, INDE 14166. Oil on canvas. Original size, 24 x 20 in.

This message to Cuba, forwarded to the court of King Carlos IV in Madrid, was signed by Vincent Folch, the Spanish governor of West Florida. In reality, Folch was only the translator. The original version was written in English by James Wilkinson, Commanding General of the U.S. Army. For this covert advice, and a promise of more to come, the Spanish paid Brigadier General Wilkinson $12,000 in newly minted Mexican silver. Forwarding the message to the Marquis of Casa Calvo, his paymaster in New Orleans, Wilkinson wrote on 12 March 1804: “The Memorial which accompanies this Letter has its origin in the anxious solicitude which I feel for the prosperity of the two Powers, which I love equally … ” He also gave instructions on how future contacts should be made: “My name or condition shall never be written, and always shall be designated by the number 13. All our correspondence must be carried on in cypher; in general it shall be with Your Excellency alone, or in case that is impracticable, with Governor Folch … “[3]Wilkinson to Casa Calvo quoted in Abernethy, Thomas P., The Burr Conspiracy (Oxford University Press, New York, 1954), 11-12. The original is in the Archivo Historico Nacional, Madrid.

This wasn’t Wilkinson’s first sellout to Spain. In fact, Number 13 claimed Madrid owed him an additional $8,000 in back pay for previous services, which stretched all the way back to a 1787 plot to convert Kentucky into an independent ally of Spain. Wilkinson kept finding ways to live well on a soldier’s pay. An officer in America’s Revolutionary army, he later fought Indians in Ohio and through seniority rose in the Adams administration to one-star rank, the highest then authorized by Congress. Both business and military duties made him a frequent visitor to New Orleans, where a French official tagged him as “an illogical fellow, full of queer whims and often drunk … “[4]Pierre Clément de Laussat, French prefect at New Orleans, 7 April 1804, quoted in Robertson, Louisiana, 2:53. As one painfully balanced biography put it: “His important services as a soldier, Indian administrator, pioneer trader, and Western expansionist were frequently forgotten in the opposition caused by his tricky unscrupulousness. “[5]Hay, Thomas R. and Werner, M.R., The Admirable Trumpeter: A Biography of General James Wilkinson (Doubleday, Garden City, 1941), ix.

Lewis and Clark Connection

In the small world of Federal service, both Lewis and Clark were well acquainted with Wilkinson. During the army’s 1793–95 Ohio campaigns against Chief Little Turtle, Lieutenant Clark was one of the junior officers who admired the flashy Wilkinson more than the top commander, General Mad Anthony Wayne. In 1807, Wilkinson had made himself so unpopular as governor of Upper Louisiana that Thomas Jefferson decided to replace him with Meriwether Lewis, the returned hero of the Rockies.

Of course, Lewis and Clark knew nothing of Number 13’s specific treachery of urging Spain to intercept their expedition in 1804. At least partly in response, Spanish officials tried to find the American explorers with Indian surrogates or Mexican troops, but were foiled by the immensity of the Western plains.

Suspicion about a cozy tie with Spain actually had swirled around Wilkinson for years. In 1797, a tip about the general’s seeming involvement in the Kentucky plot came to Washington from a Federal boundary surveyor in Natchez, Andrew Ellicott, who later coached Lewis on celestial navigation.[6]Hay and Werner, 171-172. In 1810, during a House of Representatives inquiry into charges that Wilkinson “corruptly received money from the government of Spain or its agents,” surveyor Isaac Briggs (another of Lewis’s astronomy teachers) said the general admitted receiving “about” $10,000 from Spain back in 1804.[7]Briggs deposition to the House of Representatives, 13 April 1810. Isaac Briggs Papers, Library of Congress.

History’s Verdict

But nobody could ever quite corner the slippery general. Jefferson had heard all the rumors, but seemed eternally grateful to Wilkinson for his role in blowing the whistle on the murky Western intrigues of former Vice President Aaron Burr. Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin conceded in 1806 that the rumors should “induce caution” about Wilkinson, but added: “Of betraying his [country] to a foreign country I believe him to be altogether incapable.”[8]Gallatin to Jefferson, 12 February 1806, quoted in Malone, Dumas, Jefferson the President, Second Term. (Little,Brown,Boston, 1974)p. 224.Editor’s Note: The original source sheds more light on … Continue reading

Not until a century later did the smoking-gun documents showing the depth of Wilkinson’s guilt turn up in the archives of Madrid and Seville. There, American historian Isaac Cox and others found a letter from Don Vincente Folch identifying Wilkinson as the true author of the 1804 “Reflections on Louisiana,” and the “Number 13” cover letter from Wilkinson to the Marquis de Casa Calvo. Cox disclosed his findings in a paper read at a meeting of the American Historical Association on 30 December 1913, and published the following year in the American Historical Review.[9]Cox, Isaac J., “General Wilkinson and His later Intrigues With the Spaniards,” American Historical Review. Vol. 19. No. 4 July 1914, letter from Gov. Folch to the Captain-General of Cuba … Continue reading

Had Spain actually stopped Lewis and Clark, history’s verdict on Wilkinson’s role doubtless would be harsh indeed. But as things turned out, his spying merely produced the kind of irrelevant fizzle that so of ten plague undercover intrigues by governments. “We may doubt if the Spanish got their money’s worth,” concluded Jefferson biographer Dumas Malone. “He seems to have told them little they did not know already or could not have easily ascertained, and he may have suggested little or nothing they would not have thought of anyway.”[10]Malone, 219.

Related Pages

The expedition had one major outcome that was made available to the public well before the expedition was over, the “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” which Lewis and Clark sent back on the barge in April 1805.

This Arikara leader rode upriver with the expedition in the weeks that followed to negotiate a peace settlement with the Mandan. In the spring of 1805 he went down river with the barge to St. Louis. After a series of delays, he went to Washington, DC, to meet with President Jefferson.

Ellicott was one of the best surveyors of his time, renowned today for the accuracy of his work. He was appointed Surveyor General of the United States in 1792. Ellicott’s personal history was particularly applicable to the mission at hand.

Fur Trade after the Expedition

by W. Raymond Wood

The Louisiana Purchase and the lure of its beaver population led to a veritable flood of traders and trappers moving toward the Upper Missouri and the Northern Rocky Mountains and the slow abandonment of the overland trade in the United States by Canadian and British interests.

Six years before signing on with the Lewis and Clark Expedition, George Drouillard took part in a sensitive international mission for the United States Army. This mission was probably just one of Drouillard’s many services to the United States in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

November 14, 1803

End of the Ohio

The expedition sets up a camp at the mouth of the Ohio. In Washington City, a report on Louisiana is presented to Congress with information about a mountain of rock salt and Spanish land grants.

The Mouth of the Missouri

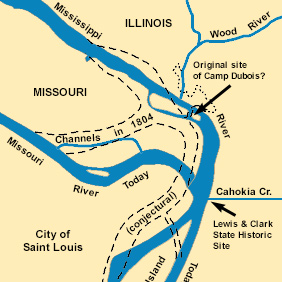

by Joseph A. Mussulman

The Missouri River still contributes its tint a few miles north of St. Louis. It is difficult to determine exactly how much, and how often, the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi Rivers changed during the nine decades after the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

March 5, 1804

Wilkinson's sedition

On or near this date, the commander of the U.S. Army James Wilkinson advises Spain to block the Lewis and Clark Expedition—an act of sedition. The captains continue in St. Louis, the others at Wood River.

March 24, 1804

Reflections on Louisiana

At winter camp on the Wood River, Clark sends out letters. Sometime this month, the Commanding General of the U.S. Army secretly advises Spanish officials to stop the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Narrated in both English and Spanish, Daniel Flores tells the story of a parallel, southern exploration now nearly forgotten.

Narrado tanto en inglés como en español, Daniel Flores narra la historia de una exploración paralela y sureña ahora casi olvidada.

June 13, 1805

"sublimely grand specticle"

At the Grand Fall, Lewis marvels at the “sublimely grand specticle”. Downriver, Clark gives Sacagawea a dose of salts. At Fort Massac, General Wilkinson has questions about the people sent to him in the barge.

June 15, 1805

Sacagawea deteriorates

Below the Great Falls of the Missouri, Sacagawea‘s health deteriorates, and Charbonneau asks her to return home. Several miles ahead, Lewis fishes and describes a prairie rattlesnake in minute detail.

February 12, 1806

Two Oregon grapes

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, Lewis describes two species of Oregon grape, and three Clatsop dogs are brought as payment for missing elk meat. In Washington City and Madrid, suspicions grow.

September 3, 1806

News from home

Moving down the Missouri, they meet a group of traders who tell them that Jefferson is again president and that Alexander Hamilton died in a duel with Aaron Burr. They camp above present Sioux City, Iowa.

September 10, 1806

News of Zebulon Pike

Fur traders heading up the river tell the captains that Zebulon Pike is leading an expedition to the source of the Arkansas River. They end the day near present Bean Lake, Missouri.

September 17, 1806

News from James McClallen

After passing through the perilous Malta Bend, the captains meet an old military acquaintance of Lewis’s, James McClallen. He reports that most people have given up on Lewis and Clark.

Notes

| ↑1 | The remainder of this article is an extract from We Proceeded On the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation: Arlen J. Large, “Lewis and Clark Under Cover”, We Proceeded On, August 1989, Volume 15, No.3, 20–22. The original, full-length article is provided at lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol15no3.pdf#page=12. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robertson, James A., ed., Louisiana Under the Rule of Spain, France, and the United States 1785-1807 (Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, 1969 reprint of 1910-11 edition), 2:334, 338, 342. Robertson was unaware of the true authorship of “Reflections on Louisiana,” citing it as proof of Gov. Folch’s “hostility toward the Americans.” |

| ↑3 | Wilkinson to Casa Calvo quoted in Abernethy, Thomas P., The Burr Conspiracy (Oxford University Press, New York, 1954), 11-12. The original is in the Archivo Historico Nacional, Madrid. |

| ↑4 | Pierre Clément de Laussat, French prefect at New Orleans, 7 April 1804, quoted in Robertson, Louisiana, 2:53. |

| ↑5 | Hay, Thomas R. and Werner, M.R., The Admirable Trumpeter: A Biography of General James Wilkinson (Doubleday, Garden City, 1941), ix. |

| ↑6 | Hay and Werner, 171-172. |

| ↑7 | Briggs deposition to the House of Representatives, 13 April 1810. Isaac Briggs Papers, Library of Congress. |

| ↑8 | Gallatin to Jefferson, 12 February 1806, quoted in Malone, Dumas, Jefferson the President, Second Term. (Little,Brown,Boston, 1974)p. 224. Editor’s Note: The original source sheds more light on Gallatin’s opinion: Of the General I have no very exalted opinion, he is extravagant and heady, & would not I think feel much delicacy in speculating on public money or public land. In both those respects he must be closely watched; and he has now united himself with every man in Louisiana who had received or claims large grants under the Spanish Govt. (Gratiot, the Chouteaus, Soulard &c) But, tho’ not perhaps very scrupulous in that respect, and although I fear that he may sacrifice to a certain degree the interests of the U. States to his desire of being popular in his Government, he is honorable in his private dealings; and of betraying his to a foreign country, I believe him altogether incapable. Yet Ellicots information, together with this hint may induce caution; and if any thing can be done which may lead to discoveries either in respect to him or others, it would seem proper; but how to proceed I do not know.Albvert Gallatin to Thomas Jefferson, 12 February 1806, Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/99-01-02-3223 accessed 11 May 2022. |

| ↑9 | Cox, Isaac J., “General Wilkinson and His later Intrigues With the Spaniards,” American Historical Review. Vol. 19. No. 4 July 1914, letter from Gov. Folch to the Captain-General of Cuba describing a preliminary conversation with Wilkinson, in which the general agreed to pu this “Reflections on Louisiana” in writing. Folch’s letter was found in the Cuban Papers, Archives of the Indies, Seville. |

| ↑10 | Malone, 219. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.