Hugh Heney had been an innkeeper in Montreal before becoming a free trader in 1800. In 1804 he joined the North West Company, a bitter rival of the long-established Hudson’s Bay Company.[1]The Hudson’s Bay Company was organized in England in 1670, not only to carry on fur trading with Indians in the territory surrounding Hudson Bay, but also to search for the legendary Northwest … Continue reading As a free trader he had established a positive relationship with the Sioux Indians who were, according to Clark, “Visious,” but had “behaved tolerably well to the only trader Mr. Haney.”[2]“Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” in Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 3:417. The … Continue reading Stationed at the North West Company’s Fort Assiniboine, near the mouth of the Souris (Mouse) River, Heney, whom Lewis characterized as “a gentleman of rispectability,” made two trips to the Knife River Villages during the winter of 1804–5, and shared a considerable amount and variety of information with the American captains. Moreover, Heney had expressed his willingness to help their government in dealing with the Indians he knew best—perhaps seeing this as a way of subverting the HBC’s power among the Indians in that part of the continent.[3]Their conversations must have been wide-ranging, for Heney also sent two messengers on a 300-mile round trip from Fort Assiniboine to deliver a specimen of “a plant common to the praries in … Continue reading Although Lewis and Clark had nothing particular to suggest at that time, they kept his offer in mind.

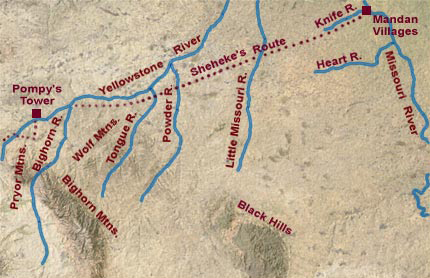

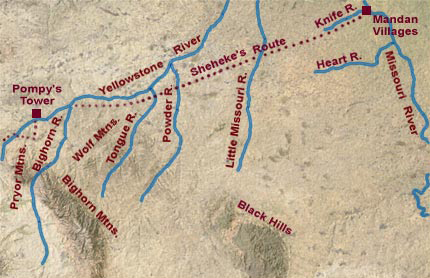

Sometime before the Corps of Discovery’s arrival back at Travelers’ Rest at the end of June 1806, the captains composed a long letter to Heney, reminding him of his offer and appealing to his personal interests as well as those of the United States. They asked if he would try to persuade “the most influensial Chiefs” of the Lakota Sioux, Sisseton and Yankton Sioux, to visit President Jefferson, and himself escort them back to Washington, D.C., preferably in company with the returning Corps. They especially wanted Teton Sioux chiefs included, because their people would “always prove a serious inconveniance” to fur traders aiming for the upper Missouri or the Yellowstone.

Related Pages

There was no Northwest Passage by water; and the portage they found took much longer than a day. The political repercussions from that alone could be immensely embarrassing to Jefferson. Something had to be done….

December 16, 1804

A letter from Chaboillez

At Fort Mandan, traders Hugh Heney and François-Antoine Larocque bring a letter from the manager of Fort Assiniboine of the North West Company accompanied by George Budge of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

December 17, 1804

North West Company intelligence

Visiting North West Company clerk Hugh Heney gives the captains maps of the Missouri River between Fort Mandan and the Rocky Mountains. Mandan visitors report that a bison herd was scared away.

February 28, 1805

Arikara and Sioux news

Traders arrive at the Knife River Villages with news and two plant specimens for Lewis. About six miles from Fort Mandan, several enlisted men cut down cottonwood trees to make dugout canoes.

Via the shorter route, Pryor would have arrived at the Knife River villages by about 6 August 1806. A trip to see Hugh Heney at Fort Assiniboine would take another two weeks.

Notes

| ↑1 | The Hudson’s Bay Company was organized in England in 1670, not only to carry on fur trading with Indians in the territory surrounding Hudson Bay, but also to search for the legendary Northwest Passage to the Pacific. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Estimate of the Eastern Indians,” in Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (13 vols., Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001), 3:417. The captains also engaged Pierre Dorion, Sr. |

| ↑3 | Their conversations must have been wide-ranging, for Heney also sent two messengers on a 300-mile round trip from Fort Assiniboine to deliver a specimen of “a plant common to the praries in this quarter,” the root of which he claimed to have used successfully in the treatment of “the bite of the made wolf or dog and also for the bit of the rattle snake.” The plant has not been positively identified, and the specimen, which Lewis sent to Jefferson along with a few pounds of the root, has never been found. Donald Jackson, ed., Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854 (2nd ed., Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:220. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.