The Long Room, Interior of Front Room in Peale’s Museum (1822)

By Charles Willson Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale

Watercolor over graphite pencil on paper, 14 × 20 3/4 in, Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, Director’s Discretionary Fund, 57.262.

This was CWP’s preliminary sketch for his large self-portrait, “The Artist in his Museum,” drawn as an experiment with the device he had invented for plotting perspective. His son Titian filled in details with watercolors. Charles Willson wrote to Titian’s brother Rubens that “the minutia of objects” made it a laborious task, but it looked beautiful through a magnifying glass.[1]Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” 47. The busts at right, opposite the door, are by Houdon; one is of George Washington, the other of Benjamin Rush.

Founding

Benjamin Franklin returned from Paris in 1785. Peale, along with other men of differing political opinions and some notable foreigners, was elected to the American Philosophical Society. Old political animosities seemed (at least to Peale) to be dying; a new country was bright with promise. Franklin encouraged the museum idea, and Peale received advice and eventually much more from the Society.

The idea for the museum took shape in 1784. Peale then had in his possession mastodon bones from Big Bone Lick on the Ohio River; he had been commissioned to draw them. Colonel Nathaniel Ramsay, Peale’s brother-in-law, enthusiastically examined the bones and thought them even more of an attraction than the portrait gallery. Peale discussed the idea of a museum of natural history with others, particularly Robert Patterson (a secretary of the APS who would later be one of Meriwether Lewis‘s Philadelphia tutors). Patterson gave Peale what would forever after be labeled the first gift to the museum: a preserved paddlefish.[2]Polyodon spathula. (The generic term is Greek for “many-toothed”; the specific epithet spathula refers to the flat, spatula-shaped snout.) Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s … Continue reading

Peale was the right person at the right time. His artistic talent, love of public approval, energy and enthusiasm for the new and untried suited him to the task. It was a patriotic project as well, intent on showcasing the natural treasures of the new country. Models of museums existed in Europe, where national institutions had developed from private collections. Indeed, from the start Peale saw his museum as a national one that would eventually be funded by the government, although despite his best efforts and closeness personally to many of the political elite—and until 1800 being located next to the seat of government—such funding proved chimerical.

Peale’s museum was not the first in America. In the 1770s the APS itself had a “cabinet,” and Charlestown, Pennsylvania, attempted to establish a museum.[3]George Gaylord Simpson, “The First Natural History Museum in America,” Science, n.s. vol. 96, no. 2490, 18 September 1942, 261-63. Pierre Eugène Du Simitière, a painter like Peale, had established a natural history museum in Philadelphia in 1782, a rather small, personal operation open for a limited time each week. Du Simitière died in 1785, and his collection broken up.[4]Martin Levey, “The First American Museum of Natural History,” Isis, vol. 42, no. 1 (April 1951), 10-12. Peale’s institution would be the first museum in America that we would recognize as such.

It is possible to view Peale’s enterprise as a precursor of the Smithsonian. Although a private enterprise, it had a close association with U.S. government, which provided some support—making the State House available as a venue, for instance. Specimens from government expeditions were deposited there. The collection was “Smithsonian” in breadth. Public education was an important part of its mission. But in Peale, the indefatigable promoter, one can observe the outline of P. T. Barnum. While Peale’s museum was never like the boisterous freak show that Barnum created, keeping the interest of the public—providing “rational amusement” as Peale termed it—and creating a steady income were important. There was the search for the novel and exotic (the five-legged cow stayed on display), the musical entertainments in the evenings, the organ in the museum, the booth with the physiognotrace (a machine for making silhouettes, see Profile Portraiture), and the exploding of the small wooden house by electricity, all done with the intention of keeping the public’s interest and increasing profits.

18th–century Enlightenment

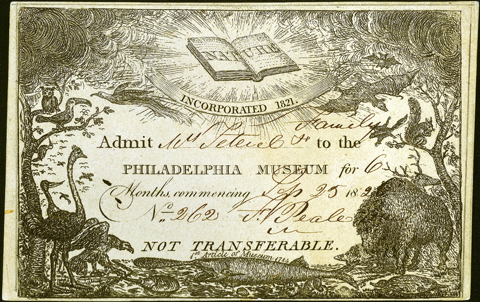

Above is a ticket of admission to Peale’s museum, dated 25 September 1826, and signed by Franklin Peale (1795-1870). Nature is symbolized by an open book promising the secrets of some of the creatures represented by mounted specimens in the museum. Clockwise from lower left those include: bald (American) eagle, ostrich, [shorebird?], woodpecker, toucan, great horned owl, pheasant, two bats, flying squirrel, tree squirrel, elk, bison, soft-shelled turtle, porcupine, several crustaceans, and a crab. The paddlefish at bottom center, labeled “1st Article of Museum 1784,” was Robert Patterson’s contribution to the Museum.

Peale’s Museum, however, is most accurately seen as an 18th century institution, one that, as Hart and Ward write, “reflected eighteenth-century Enlightenment and republican ideas about order, harmony, and civic virtue.”[5]Sidney Hart and David C. Ward, “The Waning of an Enlightenment Ideal: Charles Willson Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, 1790-1820,” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 8, no, 4, … Continue reading Nature was ordered, harmonious, God’s perfect creation. Contemplating the endless variety of the “great chain of being” brought one closer to understanding God’s benevolence:

In any one of the departments of animal Nature the variety is so great of the wonderful provision to sustain and keep in equal equilebriam each sustaining link to complete a whole system, as must astonish every being who contemplates the perfection of these regulated laws stamped on them by an allwise, all good, and all benevolent power!

The virtues in Nature can promote virtue in humanity. Would that ministers more frequently “illustrate the goodness of the almighty in the provisions he has made for the happiness of all his creatures, that excellent code of Christianity would produce more voteries of Charity; love and forbearance with each other.”[6]Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 271-72. Throughout this essay quotations from Peale’s writings are presented verbatim.

Educating the public in Nature’s virtues—displaying, for the public’s benefit, “the world in miniature”—also promotes civic virtue, an educated public being necessary for the survival of a republic. “In a country whose institutions all depend upon the virtue of the people, which in its turn is secure only as they are well-informed, the promotion of knowledge is the first of duties.”[7]Charles Willson Peale, “Memorial to the Pennsylvania Legislature,” from American Daily Advertiser, Dec. 26, 1795, Peale Papers, vol. 2 (Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum … Continue reading And citizens, regardless of formal education, could study “the open book of nature” to discover directly the truth of God’s world, either on their own or laid out in Linnaean order in Peale’s museum.[8]Peale also gave a series of public lectures beginning in 1799 that served both to educate the public and promote the educational stature of the Museum. Just as important, the study of all Nature—animate and inanimate, plants and animals and humans—would secure for all humankind future health, happiness, and prosperity. The American Philosophical Society was founded upon such an idea. “Philosophy” in the 18th century was broadly conceived as all knowledge, and knowledge had unity and utility. Explaining the nature of electricity or heavenly motion, describing new species, and developing a new plow were not qualitatively different acts.

Charles Willson Peale would for about two decades devote himself mainly to his museum. In April 1794 he announced he was giving up portrait painting. He did everything in the museum, his family assisting: promotion, obtaining and mounting specimens (family bird hunts occurred regularly), painting backdrops, caring for live specimens, arranging the museum systematically, working to improve attractions and display space. Instrumental in the success of the museum was his association with the APS. Elected a member in 1786, Peale, after initial irregular attendance, attended meetings regularly, serving as curator of the APS collection, writing pieces for Transactions, seeking advice and support from members, and literally setting up shop in the APS’ building, Philosophical Hall.[9]Peale attended only two meetings after 1811; General Lafayette was present at one of them. APS Minutes, 1805-1828.

Age of Jefferson

“Exhuming the First American Mastodon” (1806-1808)

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), Oil on canvas, 49 x 61½ inches. Courtesy Maryland Historical Society.

Down in the pit, workmen are digging marl and hoisting it to ground level to be sifted for fossils. To deal with the continuous seepage into the pit, Peale constructed a special pumping system. It is a continuous conveyor belt of water buckets powered by a large turnspit, propelled by three men walking forward, in step, inside it. The water is conveyed off-site through a trough.

Peale peopled his scene with more than fifty anonymous workmen, plus nearly twenty of his family members and friends. In the foreground, ascending the ladder from the pit, is Mr. Masten, the owner of the farm where the dig was located. At ground level, under the left leg of the structure supporting the conveyor belt, stand Elizabeth DePeyster Peale, the artist’s second wife (deceased at the time he painted the picture), and their son, Titian. Almost hidden behind the right leg of the structure are two of the artist’s other sons, Linnaeus and Franklin. At the boys’ left stands James Peale. At left in the background, wearing a blue coat and standing beside Peale’s tent-like tool room, is his good friend, the poet and ornithologist Alexander Wilson (1766-1813). In the distant background is the army officer’s tent where Peale slept. At right the artist, who has been displaying his painting of a full-scale mastodon leg, acknowledges one of the workmen in the pit who, coincidentally, has just discovered a leg bone of a mastodon!

More members of Peale’s family are shown below in a closeup from Peale’s famous “mammoth picture.”[10]Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale and ‘The Mammoth Picture’,” The Peale Museum Historical Series, Publication No. 7, February 1951 (Baltimore: Municipal Museum … Continue reading

—Earle E. Spamer and Richard M. McCourt

Peale’s museum philosophy has been summarized to show how closely it was associated with the new Republic’s conception of itself. The heyday of the museum was during what has been called the age of Jefferson.[11]John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson. Ames, Iowa State University Press, 1984. Jefferson was President of the United States and simultaneously president of the American Philosophical Society. He and Peale held similar political views (although the artist had given up politics as such). Certainly Jefferson supported and helped to sustain Peale. The two men corresponded regularly, their relationship being closest during the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the same time when Peale was promoting his polygraph, the machine capable of producing two copies of a document at once that both he and Jefferson used.

But a real intellectual connection existed in the two men’s belief that the study of nature in all its manifestations promoted republican virtue and aided in improving the welfare of humankind. Meriwether Lewis imbibed the ideas of the age of Jefferson while serving as his secretary. Lewis and Clark’s trip was organized as a military expedition and had economic and geopolitical goals, but Lewis, surveying the vast country he traversed, saw the “open book of nature” displayed before him, its beauty and variety inspiring poetic journal entries, all the while seeing the utility of the plants, animals, minerals, and soil he found, observing and recording the cultures of the peoples he encountered. If the expedition can be said to have carried with it a philosophy, it was the study of nature and man as Jefferson and Peale viewed it.

Family Affair

Above, holding up his painting of the leg bones of a mastodon, is the artist, Charles Willson Peale. From his left are: Hannah Moore Peale, his third wife; Mrs. Rembrandt Peale (probably); her husband and his eldest son, Rembrandt. The two children are the artist’s daughters, Sybilla Miriam Peale and Elizabeth DePeyster Peale. Behind them, hatted, stands CW’s son Rubens, at whose left is another brother, Raphaelle, holding the roll of the painting. Peering over Rubens’s left shoulder is Mrs. Raphaelle Peale. In the background, beneath an umbrella, Coleman Sellers is speaking to his wife, Sophonisba Peale Sellers, a daughter of the artist.

—Earle E. Spamer and Richard M. McCourt

Peale largely eliminated the moving picture show by 1786, using its space for the artifacts and specimens he began acquiring, and expanded his property at Third and Lombard Streets in 1785, which made room for the live specimens that were among the donations. For several months in 1786 he published an appeal in the Pennsylvania Packet and other newspapers for “Natural Curiosities.”[12]Sellers, Museum, 22-24.

A pattern of work and life around the museum established itself early. Specimens and artifacts were received either through donation or exchange with others, or were gathered by family members. Hunting expeditions were frequent occurrences, especially for birds. Charles Willson wrote constantly to friends, men of science, and European institutions, seeking advice or specimens to exchange. He published public notices, appealed to political leaders for funding. Meanwhile, the arrangement of the museum occupied much of his time, especially preserving and mounting specimens. There was a constant search for ways to enhance the museum and keep the interest of the public.

The entire operation was very much a family affair, and the Peale family was large. Charles Willson’s first wife, Rachel, died in 1790, his second, Elizabeth DePeyster, in 1804, and his third, Hannah Moore, in 1821. Altogether they bore him seventeen children, ten of whom survived past their twenty-first birthday. Growing up a Peale was an experience like no other, being surrounded by all types of animals, stuffed and mounted or yet alive, someday to be mounted; meeting important people, seeing the daily crush of ordinary citizens; being the first to greet a ship’s captain bringing something new to donate from Tahiti or Africa; closely involved behind the scenes in the creation of the grand institution that often dazzled its visitors.

The Peale boys especially were deeply involved. The eldest, Raphaelle (1774-1825), a talented painter of still-life, worked extensively preserving animals, in the process ruining his hands in the harsh chemical solutions. He and his brother Rembrandt (1778-1860) attempted to establish a museum in Baltimore (some years later Rembrandt himself succeeded), and Raphaelle even presented lectures at the Philadelphia museum in which his performing skills shown, but he died relatively young of alcoholism.

Rembrandt Peale was the most dedicated and artistically successful painter among the Peale children, but he never could quite make a living at it and used museum work to subsidize his painting. Rembrandt and Rubens ran it from 1810 until 1822, their father relinquishing museum operations to enter a very busy retirement on a farm he named “Belfield.” The siblings worked hard to increase the profitability of the museum. While the institution maintained primarily a scientific nature, exhibits and “curiosities” that were purely entertaining were often introduced, among them a tattooed human head, programs featuring human prodigies such as a six-year-old mathematical genius from Vermont, and the first penny weighing machine in the United States.

Titian Ramsay (1799-1885), the second son by that name, and Franklin (1795—1870) ran the museum after their father’s death. Both had literally grown up with it, having been born in Philosophical Hall after the family and its museum moved there. Franklin would eventually obtain a position as Chief Coiner at the United States Mint. Titian was the most accomplished naturalist among the Peale sons.

Titian served as assistant naturalist on Stephen Long’s government-sponsored expedition to the Rocky Mountains (1818-1821), creating many drawings of plants and animals. Many of the expedition’s specimens ended up in Peale’s museum. He did the same on Charles Wilkes’s Expedition to the South Seas (1838-1842). His main responsibilities were to preserve specimens of birds and animals and to draw pictures of them in their native habitats. Among the books Titian contributed drawings to were Charles Lucien Bonaparte’s continuation of Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology, Thomas Say’s American Entomology, and John Godman’s American Natural History.

Public Promotions

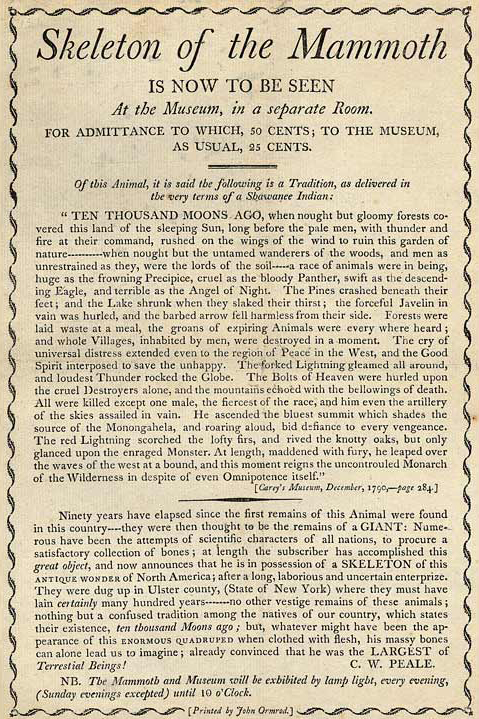

At the end of the 18th century this sort of advertisement was called a broadside. Today we’d call it a flyer. This one, which Peale first published in 1801, was reprinted in Samuel Goodrich’s First Book of History: For Children and Youth (Baltimore, 1831) as a reminder of a historical event.

The ups and downs and changes in the museum over its life (roughly 1784-1845) could be discussed at length, participating as it did in so many ways in the early history of the United States, but we’ll content ourselves here with addressing only two aspects of the museum’s history: its growth, and the unearthing and exhibiting of the “mammoth.”

As with all collecting institutions, Peale’s museum never seemed to have enough space. In 1794, the property at Third and Lombard proving inadequate, Peale launched his first major attempt to obtain public funding for a museum building. The state legislature was spared having to make a funding decision when the prestigious American Philosophical Society offered to rent most of its own Philosophical Hall to serve as both a museum and the Peale family home. The museum’s live animals could be caged on State House Yard (today’s Independence Square). The move to the Hall took two weeks, the climax of which was a parade of the collection. As Peale recounted in his Autobiography, he:

hired men to go with the hand barrows, but to take the advantage of public curiosity he contrived to make a very considerable parade of the articles, especially of those which was large, and as Boys generally are fond of parade, he collected all the boys of the neighbourhood & he began a range of the[m] at the head of which was carried on mens shoulders the American buffalo, then followed the Panther, Tyger Catts and a long string of Animals of smaller size carried by the boys. The parade from Lumbard to the Hall brought all the Inhabitants to their doors and windows to see the cavalcade. It was fine fun for the Boys.[13]Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 224-25. The Autobiography is written in the third person.

The spectacle saved Peale money, gained him free publicity, and only cost him the loss of two minor items.

Mammoth Appeal

1801 was an important year for the museum. Jefferson was simultaneously president of the United States, president of the APS, and president of the museum’s Board of Visitors. The “mammoth” (in reality a mastodon) had been excavated and reconstructed. Public funding seemed ever closer. More space was needed. Peale proposed a lottery to fund a building on State House Yard and had his friend, the architect Benjamin Latrobe, design one. The looming success of the venture and the potential loss of the park induced the City of Philadelphia and the APS to strongly recommend the state let Peale use the State House (Independence Hall). On the conditions that Peale maintain the building and provide use of the Declaration Chamber on election days, the Assembly in March 1802 granted the use of most of the building. For the next decade the museum enjoyed its golden age; it was in the State House that the Lewis and Clark artifacts were first displayed to the public.

The mammoth remained in Philosophical Hall until 1801, when Rubens consolidated the museum in the State House. The City first began charging rent in 1815, the charge being preferable to maintaining the building. In 1816, the State sold the building to the City, which, learning how much the museum made, quintupled its rent to $2,000 per year, a potential disaster for funding improvements and programs. In 1819 the rent was reduced to $1,200. Two years later, to prevent the museum’s moving from the city, a stock company was formed, with Charles Willson, who had again become active in museum affairs, was at first the sole stockholder. The rent was cut to $600 per year, but nothing in the collection could leave Philadelphia without Peale paying double its value to the City.[14]Sellers, Museum, 229-39.

The museum stayed in the State House until 1827. Plans were made for a new building—the first office building in America—designed by architect John Haviland. The building, on Chestnut between Sixth and Seventh, could have a third floor added for the museum. Peale did not live to see the museum move to Haviland’s building. After his death that year his sons and family associates took over the corporation.[15]In 1838 the museum would move again to yet another new building, at Ninth and George (Sansom) Streets. Financial difficulties and irregularities were then constants. Later deals left the … Continue reading

One constant in the museum from 1801 on was the skeleton of the mastodon, often called a mammoth, although the two words soon came to denote two different species (and William Clark played a key role in that process). It’s hard to overestimate the effect that the discovery and display of the animal had on people at the time. The exhibit was so popular that a separate fifty-cent admission could be charged for it—double the museum admission—and “mammoth” quickly became a popular adjective to describe anything that was huge. Apparently it began its migration into the vernacular in 1802 with its application to a 300-pound cheese that President Jefferson received as a gift.

Fossil evidence of the “American Incognitum” had been emerging for some years. David Rittenhouse and Andrew Ellicott (one of Lewis’s Philadelphia-area tutors) had found a tooth of one on the upper Susquehanna River in 1786. Peale drew a picture of the tooth, which appeared in Columbian Magazine. George Turner, a member of the American Philosophical Society, had read a paper on the supposedly ferocious, presumably carnivorous beast.[16]Sellers, Museum, 26, 126. Jefferson, who did not believe any species could become extinct[17]See Thoughts on Extinction, thought Lewis and Clark might find a specimen on their expedition. Lewis, descending the Ohio River, wrote Jefferson a long letter describing the bones gathered by Dr. William Goforth at Big Bone Lick in Kentucky. In 1807, Jefferson engaged Clark to conduct a dig there on his way to assume his government post in St. Louis.[18]See Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Related Documents 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:126-132.

New York Excavations

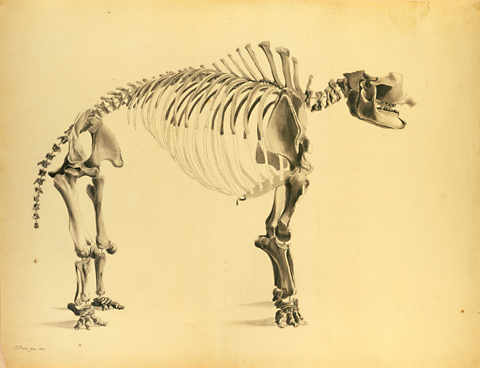

In 1821 Titian Peale created this analytical study of the mastodon skeleton, showing the bones his father had excavated at the farm of John Masten, near West Point, New York, in 1801. The lighter ones represented those the Peales had simulated, on the advice of Caspar Wistar, to produce the reconstruction for their exhibit.

News that a farmer in Ulster County, New York, wished to dispose of some bones he had found three years previously drew Peale to the farm of John Masten. It was indeed an Incognitum, damaged and incomplete but recognizable. Masten had showed the bones for money, but, as interest was waning locally, desired to sell them. “Peale, all eagerness, was careful not to seem too eager,” according to Charles Sellers, and at first only asked to make drawings.[19]Sellers, Museum, 127. Eventually a deal was struck: $300, a shotgun for Masten’s son, and gowns for his daughters.

The bones caused a sensation with their arrival first in New York (Vice-President Aaron Burr came to see them), then in Philadelphia. A well-attended meeting of the APS was held 24 July 1801. Peale’s request for a $500 loan for further excavation was granted unanimously, interest-free. Jefferson’s help was also elicited, though in the end government assistance counted less than Peale’s ingenuity.

The excavations of August and September 1801, were the first scientific expedition in the new United States. While certainly not conducted with anything approaching modern techniques, the dig proved successful, unearthing from two locations bones enough to construct most of two skeletons, one for the museum and one to take on tour in Europe.

The bones had been found in watery marl, what we would recognize today as a glacially-formed bog. To retrieve more bones, the water had to be removed. Hand pumps had been obtained, but Peale devised a waterwheel and bucket system that could remove 1,440 gallons an hour.[20]Sellers, Museum, 138. Workmen had to be paid to dig (Peale paid high wages and bowed to current medical wisdom in providing alcohol for the men working in water, though he diluted the spirits), but Peale enlisted local youth from the ever-present crowd to take turns walking inside the giant wheel to power it—a good example of Peale’s sense of show as well as a way to save money. At one memorable point, a thunderstorm threatened the operation, but with all its flash and roar, only passed nearby.

When no more bones could be found at Masten’s, the dig shifted to another area, where iron rods, devised by Rembrandt Peale and fashioned by a local blacksmith, were used to probe the soft ground for bones. One important bone missing from the first location—a lower jaw—was among the finds.

The entire operation required constant attention, and Peale succeeded admirably. He eventually commemorated the event in an epic painting in 1806-08 (see above figure), containing twenty family members and many workmen and bystanders, dramatized by the passing thunderstorm.

Once back in Philadelphia, much work was needed to assemble the skeleton, done with the assistance of Caspar Wistar, another of Lewis’s Philadelphia mentors. Missing parts were created of either papier maché or wood, the replacement parts clearly marked. When mounted, the skeleton was 11 feet high at the shoulder and 17 feet 6 inches from tusk to tail. A special Mammoth Room was created in Philosophical Hall. Handbills were printed, but the skeleton was already famous, “one of those sudden revelations of the remote past, like King Tut’s tomb, which capture both popular fancy and scholarly attention.”[21]Sellers, Museum, 142–43. Peale’s effort was his most important contribution to science, a significant contribution to paleontology.[22]See George Gaylord Simpson, “The Beginnings of Vertebrate Paleontology in North America,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 86, 1942, 130-85. Before Rembrandt Peale took the second skeleton on tour in Europe, he held a send-off dinner under the Hall’s skeleton.[23]The first survives today in the Geologisch-Mineralogische Abteilung des Hessischen Landesmuseums in Darmstadt, Germany. (See George Gaylord Simpson, “The Rediscovery of Peale’s … Continue reading

Retirement

As would be expected of an energetic member of the APS who literally lived in its Hall, Peale, prior to his “retirement” to Belfield Farm, was, beginning a few years after his election, very active in the Society. When the museum and the family moved into Philosophical Hall, Peale was named the Society’s first librarian and served 27 years as a curator. Among his many committee assignments, he drafted the first library catalog and helped in the fundraising for the proposed western expedition of André Michaux.

Peale was not a thinker but very much an observer and a hands-on experimenter, in the spirit of Benjamin Franklin and their mutual heritage as craftsmen. Peale invented, though, unfortunately, without much success: a “fan chair” operated by the sitter with a pedal, an inexpensive bridge, a fireplace that produced less smoke, and a patented steam bath. The steam-bath, intended for medicinal use, illustrates Peale’s life-long interest in medicine. Charles Willson’s ideas about medicine were similar to Jefferson’s, accepting only what proves experimentally to work and rejecting the bleeding and purging and theory practiced and taught by much of the medical establishment, especially Benjamin Rush. Peale in fact published a well-received pamphlet on healthful living, advocating a temperate life, cultivating “serenity of mind,” physical exercise, and allowing nature its place in healing sickness. Try methods yourself, Peale suggested, to see what worked.[24]Sellers, 308-310. The full title of the pamphlet is “An Epistle to a Friend, on the Means of Preserving Health, Promoting Happiness, and Prolonging the Life of Man to Its Natural Period: Being … Continue reading

Peale’s relationship with the APS was mutually beneficial but not without its tensions. The Society’s association with the Museum served to publicize the Society itself, and Peale’s enthusiasm, especially for French science, enlivened the Society. Association with the Society brought Peale into contact with the larger learned world,[25]Sellers, Museum, 81-83. and the Museum certainly made contributions to science; the most significant are arguably the exhumation and display of the mastodon and the importance of the collections to Alexander Wilson and John Godman.[26]Wilson’s American Ornithology was inspired by viewing the Museum’s collection and cites Peale’s specimens. Godman’s book is American Natural History, published in 1826. The financial arrangements were also of benefit to Peale and the Society.

However, tensions arose from the desire of Society members to support scientific pursuits as much as possible and the fact that the Museum was by design and necessity a public show. The Society was very serious about science as useful knowledge, whereas Peale, while he also took science seriously, was just as serious about educating the public, and also had to promote the Museum to attract a public to educate them and to make a living for himself. He did not see why “the public’s interest in the curious and unusual, used with care” could not be used to seek popular support of science.[27]Hart and Ward, 417. The wider world’s view of the unity and utility of knowledge—the view of Peale and of the 18th century—was breaking down at the beginning of the 19th century, even as specialized societies (in manufacturing and agriculture, for instance), were increasing in number. The fracturing of the old world view is illustrated in an incident from 1806, when the APS allowed Peale to borrow its elephant skeleton to display alongside the mastodon—but with the condition that he would not advertise the elephant.[28]For a fuller explanation of the argument in this paragraph, see Hart and Ward, 412-418.

Notes

| ↑1 | Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” 47. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Polyodon spathula. (The generic term is Greek for “many-toothed”; the specific epithet spathula refers to the flat, spatula-shaped snout.) Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum: Charles Willson Peale and the First Popular Museum of Natural Science and Art, a Barra Foundation book, (New York, W. W. Norton, 1980), 12. Hereafter cited as: Sellers, Museum. |

| ↑3 | George Gaylord Simpson, “The First Natural History Museum in America,” Science, n.s. vol. 96, no. 2490, 18 September 1942, 261-63. |

| ↑4 | Martin Levey, “The First American Museum of Natural History,” Isis, vol. 42, no. 1 (April 1951), 10-12. |

| ↑5 | Sidney Hart and David C. Ward, “The Waning of an Enlightenment Ideal: Charles Willson Peale’s Philadelphia Museum, 1790-1820,” Journal of the Early Republic, vol. 8, no, 4, Winter 1988, 392. Hereafter cited as Hart and Ward. |

| ↑6 | Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 271-72. Throughout this essay quotations from Peale’s writings are presented verbatim. |

| ↑7 | Charles Willson Peale, “Memorial to the Pennsylvania Legislature,” from American Daily Advertiser, Dec. 26, 1795, Peale Papers, vol. 2 (Charles Willson Peale: The Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810), pt. 1, 137. |

| ↑8 | Peale also gave a series of public lectures beginning in 1799 that served both to educate the public and promote the educational stature of the Museum. |

| ↑9 | Peale attended only two meetings after 1811; General Lafayette was present at one of them. APS Minutes, 1805-1828. |

| ↑10 | Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale and ‘The Mammoth Picture’,” The Peale Museum Historical Series, Publication No. 7, February 1951 (Baltimore: Municipal Museum of the City of Baltimore, 1951). |

| ↑11 | John C. Greene, American Science in the Age of Jefferson. Ames, Iowa State University Press, 1984. |

| ↑12 | Sellers, Museum, 22-24. |

| ↑13 | Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 224-25. The Autobiography is written in the third person. |

| ↑14 | Sellers, Museum, 229-39. |

| ↑15 | In 1838 the museum would move again to yet another new building, at Ninth and George (Sansom) Streets. Financial difficulties and irregularities were then constants. Later deals left the Philosophical Society with ownership of the building, an arrangement which almost bankrupted the Society. The collection, already diminishing, was eventually broken up, some of it remaining in Philadelphia, some going to New York, other bits elsewhere. Many artifacts in Philadelphia were burned in a fire in 1851. The part bought by P. T. Barnum burned in New York in 1865. Some Lewis and Clark items wound up at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. See Sellers, Museum, 294-319. [Note: Many of Sellers’ conclusions concerning Lewis and Clark’s Indian artifacts purportedly contained in Peale’s Museum and subsequently donated to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, were based on educated conjectures. Castle McLaughlin, associate curator at the PMAE, has corrected Sellers’s misunderstandings in her study, Arts of Diplomacy: Lewis & Clark’s Indian Collection (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003), 4, 9, 128, 129, 160-62, 221, 275, 319n4, 320-21n2. –Ed.] |

| ↑16 | Sellers, Museum, 26, 126. |

| ↑17 | See Thoughts on Extinction |

| ↑18 | See Donald Jackson, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and Related Documents 1783-1854, 2 vols. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:126-132. |

| ↑19 | Sellers, Museum, 127. |

| ↑20 | Sellers, Museum, 138. |

| ↑21 | Sellers, Museum, 142–43. |

| ↑22 | See George Gaylord Simpson, “The Beginnings of Vertebrate Paleontology in North America,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 86, 1942, 130-85. |

| ↑23 | The first survives today in the Geologisch-Mineralogische Abteilung des Hessischen Landesmuseums in Darmstadt, Germany. (See George Gaylord Simpson, “The Rediscovery of Peale’s Mastodon,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 98, 1954, 279-281. The second is at the American Museum of Natrual History, though not on display. |

| ↑24 | Sellers, 308-310. The full title of the pamphlet is “An Epistle to a Friend, on the Means of Preserving Health, Promoting Happiness, and Prolonging the Life of Man to Its Natural Period: Being a Summary View of Inconsiderate and Useless Habits that Derange the System of Nature, Thereby Causing Premature Old Age and Death. With Some Thoughts on the Best Means of Preventing and Overcoming Disease.” Philadelphia, Jane Aitken, 1803. |

| ↑25 | Sellers, Museum, 81-83. |

| ↑26 | Wilson’s American Ornithology was inspired by viewing the Museum’s collection and cites Peale’s specimens. Godman’s book is American Natural History, published in 1826. |

| ↑27 | Hart and Ward, 417. |

| ↑28 | For a fuller explanation of the argument in this paragraph, see Hart and Ward, 412-418. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.