Battle of Trenton

John Adams saw in the young Peale “a tender, soft, affectionate creature,” qualities which the artist himself captured in this self-portrait, painted in 1777.[1]Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum (New York: Norton, 1980), 2.

To say that Peale moved to Philadelphia during momentous times is an understatement. On 8 July, he heard the Declaration of Independence read in front of the State House, now familiarly called Independence Hall. By August Peale had joined the Philadelphia militia, called Associators, which was organized according to a plan formulated by Benjamin Franklin in 1747. The terrible, dispiriting defeats of American arms occurred in New York in September and October, followed by their retreat through New Jersey to Pennsylvania. In October Peale was elected Second Lieutenant of his militia company, and was soon promoted to First Lieutenant. While not of martial spirit, Peale, as he writes in his autobiography, “had both in public and private conversations . . . promised to do his utmost in the common cause of America [so] that when real service was called for he would never withhold his personal Service.”[2]Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 48. He would protect his family by putting himself in the line of enemy fire.

The kindly Peale was not a disciplinarian, but he led his men effectively by being very conscientious about their welfare. For instance, he polled the men about their needs, as he did the men’s families, who had to fend for themselves with their men away; while on campaign he secured hides that he turned into moccasins to replace footwear worn out by marching; and he would cook for his company as needed. Peale’s unit was under the command of John Cadwalader.

Called to active duty in December, Peale’s company sailed up the Delaware River toward Trenton, arriving in time to see Washington’s bedraggled army cross into Pennsylvania. About two weeks later, Cadwalader’s men marched south, crossed into New Jersey, and occupied Bordentown so as to block a possible enemy line of retreat when Washington attacked Trenton. A few days later the militia marched to Trenton, in time to witness a probing attack by the British, who were gathering their forces. That night, Washington, leaving a decoy force to keep fires burning, marched to Princeton to catch the British there by surprise. A British brigade, however, was already on the move by early morning, and met the American army south of Princeton. A British charge broke the first American force encountered. The fortunes of war found the nearest troops to be the Pennsylvania militia and the Continentals that Washington used to stiffen the militia. Following the lead of the Continentals, the militia formed up, poured volleys into the British, the Americans coming close to breaking and retreating. Washington, appearing where the threat was the greatest and deploying troops as they came up, provided the personal leadership that decided the outcome; the British line broke. Moving into Princeton, the Americans captured the British remnants who were barricaded in Nassau Hall. The battle was over.

Peale—who had been made acting captain—and his company marched with the army to Morristown, encamped briefly, then, the militia’s enlistments having expired, marched back to Philadelphia, leaving the regulars to their winter camp. It had been an eventful month. Washington had no confidence in militias and would rarely give them leading roles, but Pennsylvania’s rose to the occasion, acquitting itself well against the seasoned British. And Peale had been there, and seen the face of battle.

The Furious Whig

Military Intelligence

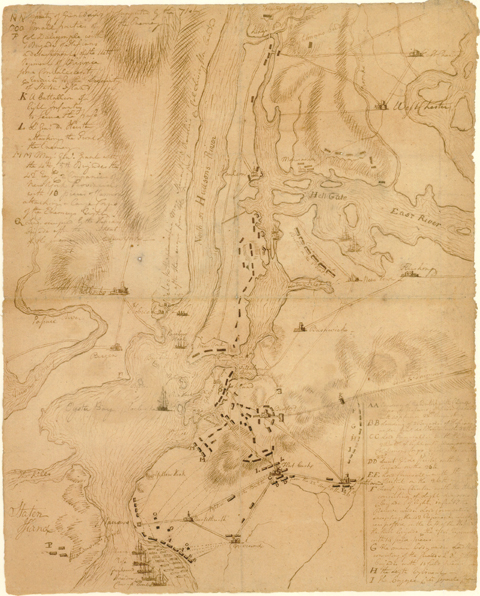

Map of British positions around New York City in 1776,

drawn by Charles Willson Peale.

To see labels, point to the image.

American Philosophical Society.

Charles Willson Peale found himself strongly drawn to the democratizing aspects of the revolution. Politics during times of upheaval are always more complicated than an easy “us versus them,” but one can still usefully divide people into two camps. Those who supported the British were called Tories; those who supported independence were called Whigs. The Whigs themselves, however, were divided into two large factions. In Philadelphia the more radical faction of Whigs, which included Peale, was in power. These “Furious” Whigs were strong supporters of the Pennsylvania state constitution of 1776, which included provisions for a unicameral legislature elected annually, a liberally-granted franchise, a president and vice-president chosen by the assembly, and a bill of rights. Referring to the Furious Whigs’ support for the 1776 constitution, Sellers writes: “Doctor, painter, lawyer, these and their shopkeeper-artisan followers stood heart and soul for a new, enlarged democracy.”[3]Sellers, Charles Willson Peale, 139. Other Whigs—sometimes called “True Whigs”—supported the break with Britain but not the radicalization of politics and governance. (True Whigs tended to be from the moneyed class.)

Peale was chosen a leader of the core group of Furious Whigs. As happens in war, action was soon taken against enemy sympathizers and other suspects. Charles Willson—diplomatic, energetic, committed—had charge of one of the committees that interviewed Tories and pacifist Quakers. It was a grim business, though fortunately at this point it did not degenerate into serious mob violence. Suspects were visited in their homes. Individuals who would not swear loyalty to the Patriot government were jailed, then three-quarters of those were sent away as a group to Virginia.

Winter of 1777

1777 was not a good year for the Patriots. Washington abandoned New Jersey. William Howe landed near Philadelphia with a plan to seize the city. For the American rebels, defeat at Brandywine was followed by defeat at Germantown. Peale managed to get his family out of the city, but conditions were perilous. As a militiaman Peale performed a number of duties, all the while painting when he could. The year ended with the British in Philadelphia, Washington in Valley Forge, and foragers for the British roaming the countryside, seizing supplies and Whigs such as Peale. In February, on Washington’s birthday, his second son, Rembrandt Peale was born, Mrs. Peale’s confinement taking place at the farm of a friend.

During the winter lull, Peale painted, spending much time at Valley Forge doing miniatures of army officers and other officials. In the spring the British evacuated Philadelphia along with 3,000 Tory sympathizers. The revitalized American army proved itself at Battle of Monmouth, and Peale and his family returned to the city. As a Furious Whig, Captain Peale was appointed to the commission to seize the property of Tories. The situation was truly revolutionary: the new order beginning to replace the old, the loyalties of individuals being questioned, the economy in turmoil, threats of violence and the collapse of public order ever-present. Peale nevertheless performed his patriotic duty as honestly as he could and without rancor, one notable incident being the eviction of the angry and resistant wife of Joseph Galloway during which Peale summoned General Benedict Arnold’s resplendent coach to carry her away.[4]Joseph Galloway, speaker of the Provincial Assembly, had left with the British.

Whigs v. Tories

Charles Willson was in the thick of events. Robert Morris, financier of the Revolution, was accused of war-profiteering from the goods of a French ship—the rich above all others perceived by the radicals as enemies. Peale was on the committee that investigated Morris, the crisis ending when the United States government purchased the questioned goods. Another crisis involved a published defense of Morris that also contained a bitter attack on Thomas Paine. The identity of its anonymous author, Whitehead Humphreys, was discovered, his house surrounded, violence threatened by the mob. Peale and another militia officer personally calmed the mob, a squad of Continentals arriving to keep the peace. The actions were misinterpreted by some, however, with Peale being pegged as a ringleader who summoned soldiers to arrest rather than protect Humphreys.

There was yet another incident. Peale mistakenly asserted that Paine had received money from Silas Deane to keep a circumspect attitude about certain French supplies. The payment—a bribe really—had actually come from a French government official, but Deane raised a stink, and the matter fed into the fervid atmosphere. Peale himself was attacked and injured on the street.

There were meetings of the radicals, meetings of their opponents (none left in the city were overtly pro-British; the more conservative faction tended to be wealthier Whigs), armed men were everywhere present and clamoring for action. A year of such turmoil came to a head on 4 October 1779. The militia met to organize the expulsion of all Tory suspects. Peale and other leaders were unable to prevent their compatriots from taking action. The mob met up with a smaller band of conservatives, who retreated to the stout house of James Wilson, later a framer of the Constitution. A shot was fired from inside the house, fighting broke out, the door of the house breached, men killed inside. Cavalry arrived to break up the fighting, and several militia men were arrested.

The next day the angry militia gathered to protest the arrests. The leaders present debated among themselves what to do, Peale suggesting that the detainees be granted bail. When this was announced to the militia, the men accepted the suggestion, and the situation was defused.

The incident at “Fort Wilson” was the most dangerous revolutionary moment in Philadelphia, violence never again reaching such a point. Peale was elected to the new State Assembly, the Furious Whigs in ascendancy.

Post-Revolutionary Politician

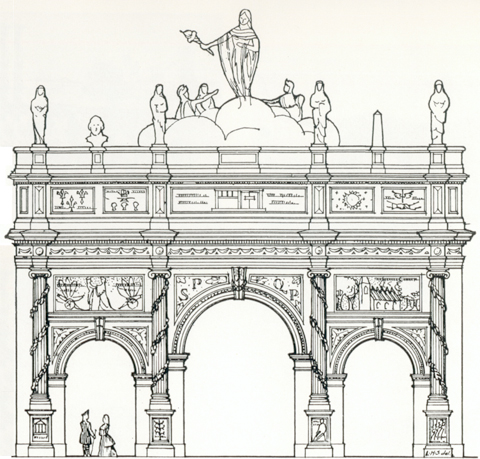

Every detail in the thrilling Arch of Triumph conceived by “the ingenious Captain Peale” contributed to the total effect, celebrating the unique identity of the new nation, its values rooted in Classical civilization, and its dedication to republican principles: The four Ionic columns “entwined with American flowers in their natural colors”; George Washington as Cincinnatus “returning, laurel-crowned, to his plow”; a library, “with emblems of art and science”; Indians “building churches in the wilderness”; due homages to France for her encouragement and support; on the balustrade stand heroic-sized statues representing Justice, Prudence, Temperance and Fortitude. The initials “S.P.Q.P.” on the spandrels of the central arch invoke the Latin words for “Senate and People of Pennsylvania.” The Arch was surmounted by a bank of clouds to which figures of Peace and her attendant dieties were to descend from nearby rooftops. This graphic reconstruction of the Arch, by the Philadelphia architect Lester Hoadley Sellers, was based on contemporary newspaper descriptions.

Charles Willson’s Revolutionary career has been recounted in some detail to give a sense of just how committed he was to revolutionary ideals and the building of a new nation, and to show the violence and disorder he experienced at its inception. Sellers writes that upon being elected to the Assembly,

the painter had reached a new eminence along this dangerous road. He was trying to maintain the part of the moderate revolutionary, as his friend Lafayette was to do with equal ill success in a later situation. He had seen the liberated masses flout every principle of freedom and he was suffering all the miseries of doubt and turbulence. But one who is “animated with the sacred love for his country,” who sees in the cluster of states the emergence of reason and virtue throughout humanity, must go on. He saw a new era dawning, vast and irrefutable forces moving forward, and to these his heart was joined.[5]Sellers, 180.

But Peale was not a politician. Conciliatory by nature, frightened by discord, an artist used to praise who suffered criticism badly, Peale was not comfortable arguing policy or outmaneuvering opposition. Never a divisive partisan, the man who could agreeably paint Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, Thomas Paine and Alexander Hamilton, was not suited for legislative halls. He was, however, eminently suited to be a proselytizer and showman. As painful as Peale’s 1780 defeat for reelection to the State Assembly was, it freed his talents for other endeavors.

Public Works

The first project was the opening in 1782 of the gallery of portraits adjoining the Peale home at Third and Lombard Streets—the first skylight gallery in America. In it were paintings of military and civilian leaders of the Revolution. The gallery was the first step on the road leading to the grand museum of the 1800s.

News of the signing of the treaty with Great Britain officially ending the War brought about a second opportunity. To celebrate the occasion, Peale constructed a triumphal arch over forty feet tall and more than fifty wide, across Market Street. Made of wood, paper, and canvas, the arch contained numerous symbols of ancient Rome, republicanism, and recent events. The extravagant construction was a “transparency,” to be backlit from inside with hundreds of lamps, with fireworks exploding overhead. Disaster struck on the appointed night. With the audience already gathered, a firework was set off prematurely, igniting the whole structure, killing one and injuring others, including Peale, who took three weeks in bed to recover. The disaster was not an auspicious start for the longed-for peace, but it was a public success nonetheless. The structure was rebuilt and shown without incident three months later.[6]Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace: A Supplement to Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale, with a Survey of His Work in Other Genres,” in … Continue reading

Moving Pictures

A third public spectacle, set up next to the portrait gallery in 1785, was made of “moving pictures,” as Peale called them. Based on techniques invented in England, the moving pictures comprised a number of scenes, one following another, constructed of transparencies, and using sound and visual effects. Eventually there were six in all: Night, A Street, A Grand Piece of Architecture (a Roman villa around which a storm broke), Pandaemonium (inspired by Milton’s Paradise Lost), Vandering’s Mill (a scenic spot on the Schuylkill River), and The Bonhomme Richard and the Serapis (of the famous John Paul Jones battle). It was another success, though the income probably didn’t justify the work involved in building it.

Notes

| ↑1 | Charles Coleman Sellers, Mr. Peale’s Museum (New York: Norton, 1980), 2. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peale Papers, vol. 5 (The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale), 48. |

| ↑3 | Sellers, Charles Willson Peale, 139. |

| ↑4 | Joseph Galloway, speaker of the Provincial Assembly, had left with the British. |

| ↑5 | Sellers, 180. |

| ↑6 | Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace: A Supplement to Portraits and Miniatures by Charles Willson Peale, with a Survey of His Work in Other Genres,” in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, n.s., vol. 59, pt. 3, (May 1969), 20, 89. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.