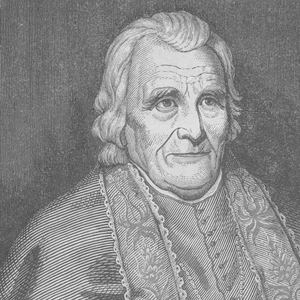

Dr. Antoine Saugrain helped organize and lead a group of emigres from Paris, across the Atlantic Ocean, to establish a settlement at Gallipolis, Ohio, in 1790. From there he moved to Lexington, Kentucky, and later, St. Louis. He had achieved status in the scientific and medical communities of St. Louis by the time he met Meriwether Lewis. Eva Emery Dye, in her book The Conquest, was the first to suggest that Saugrain made a thermometer for the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Called the “First Scientist of the Mississippi Valley,”[2]Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931), p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the … Continue reading Antoine Saugrain was a chemist and naturalist and the only physician in the frontier community of St. Louis when Lewis and Clark arrived there in 1803. Described by a contemporary as “a cheerful, sprightly little French-man”—he was just four-feet-six—he had been appointed by President Jefferson, after the cession of Louisiana to the United States, as the resident surgeon at Fort Bellefontaine, a nearby military post.[3]Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise {par} le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, … Continue reading

Antoine Saugrain was born of a distinguished royalist family in Paris in 1763, where he was educated in physics, chemistry, mineralogy and medicine. In the early 1780s, he engaged in mineralogy research in Mexico in the service of Spain. In the 1790s, he moved his wife, Rosalie Genevieve Michaud, and family to Lexington, Kentucky, where he practiced as a physician, continued chemical and mineralogy research, and fabricated and sold thermometers and barometers. In December 1797, he was attracted to St. Louis and agreed, after a grant of acreage, to establish there. He arrived in 1800, the only physician in the area and became known historically as a civic leader in the community. Saugrain had achieved unique status, scientifically and medically, by the time Lewis and Clark arrived in the area. He was available as a resource for the captains, who needed all the help they could get in specialties Saugrain could provide. Antoine Francois Saugrain de Vigny, 1783–1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise par le docteur Antoine Saugrain, etude suivie de manuscripts inedits et de la correspondance de Sophie Michau Robinson, par H. Foure Seiter (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1936).

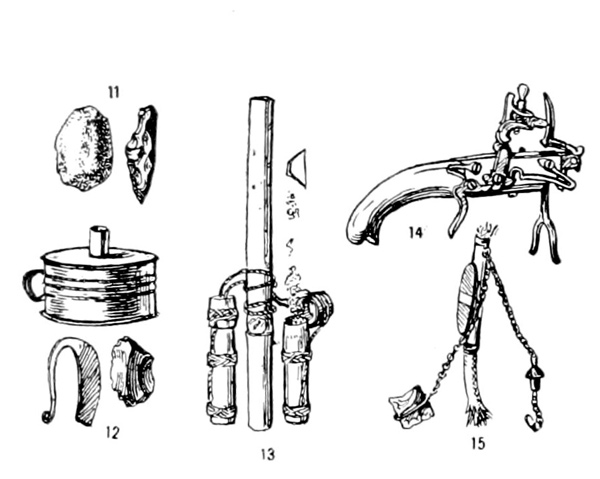

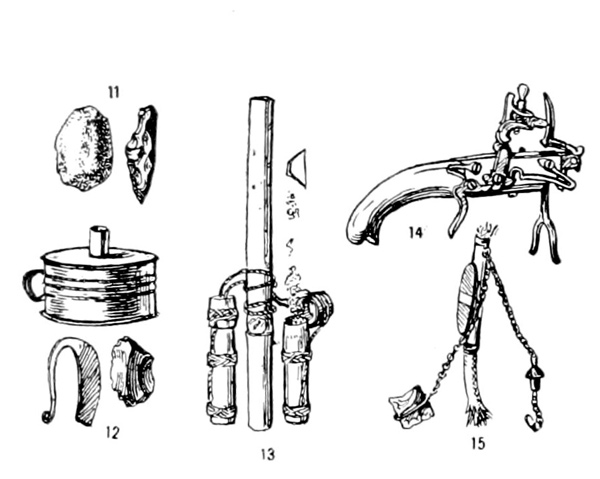

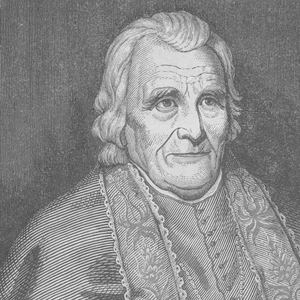

The doctor was something of a showman and seems to have liked nothing better than putting on scientific demonstrations. These included placing “little phosphoric matches” in a glass tube, sucking the air out to create a vacuum, then breaking the glass—at which point the matches ignited spontaneously. He also fabricated briquets phosphoriques—phosphorous “lighters”—and experimented with electricity, repeating the famous kite experiment of his friend Benjamin Franklin, whom he had met years before while visiting Philadelphia.[4]Ibid., pp. 3-67.

By 1800 Saugrain was settled in St. Louis. Three years later he met Meriwether Lewis. “It is inconceivable,” writes Meany, “that Captain Lewis was not familiar with Dr. Saugrain’s hobbies and vocation or that he was not frequently welcomed in the Doctor’s home and laboratory.”[5]Meany, p. 310. Given Saugrain’s eminence as a naturalist and physician, both Lewis and Clark doubtless consulted with him during their five months at Camp Dubois. The colorful doctor’s bag of tricks included “lucifers,” and it is reasonable to assume that he gave the captains at least a few of them, either for use at Camp Dubois or for later on their journey.

The Saugrain Theory

In 1905, the discussion of the expedition’s thermometers (see Thermometers and Temperatures) was enlivened during the centennial of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in Portland, Oregon, upon publication of Eva Emery Dye’s book, The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark. In the chapter on “The Cession of St. Louis,” Dye depicted Lewis at the home of Dr. Antoine Saugrain, a Frenchman known as the first scientist in the Mississippi Valley and whose daughter later became William Clark‘s sister-in-law.

In Dye’s scenario, Saugrain is eager to supply Lewis and Clark with badly needed thermometers. He turns to his wife and prepares to dismantle her mirror.

“The huge glass, that had reflected Parisian scenes for a generation before coming to the wilds of America, was now lifted from its gilt frame and every particle of quicksilver carefully scraped from the back. Then the pier plate was shattered and the fragments gathered, bit by bit, into the Doctor’s mysterious crucible . . . “[6] Eva Emery Dye, The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Company, 1902), 157–158.

Readers seeking authority for this narrative were referred to the preface of the book. Dye acknowledged obligation to many people for the authenticity of scenes in the novel, including the families of Lewis, Clark and Saugrain; scholar and expedition journal editor Reuben Gold Thwaites; and other library and newspaper sources. Scholars writing after the publication of Dye’s book have referred to her account as the basis of support for the theory that Saugrain furnished Lewis and Clark with homemade instruments.[7]Doane Robinson, “Lewis and Clark in South Dakota,” South Dakota Historical Collections 9, (1918), 557; John Bakeless, Lewis & Clark, Partners in Discovery (New York: William Morrow … Continue reading

A Family Tradition

Henry M. Brackenridge, an early traveler to the West, added to the Saugrain theory in a personal memoir. He wrote of the care given him by the doctor when he suffered from ague in Gallipolis, Ohio, in 1794: “The Doctor had a small apartment which contained his chemical apparatus, and I used to sit by him as often as I could, watching the curious operation of his blow pipe and crucible . . . His barometers and thermometers with the scale neatly painted with the pen and the frames richly carved were objects of wonder . . . “[8]L’Odysee Americaine, 24–29. Brackenridge is quoted at length, referencing “papers concerning Gallipolis belonging to the Cincinnati Historical Society.”

In his personal memoirs, Persimmon Hill, William Clark Kennerly remembered the resourcefulness of his grandfather, Antoine Saugrain, “even scraping the mercury off the back of Mme Saugrain’s pier glass . . . in order to finish in time the thermometers and barometers he made for those two great explorers . . . “[9]William Clark Kennerly as told to Elizabeth Russell, Persimmon Hill, A Narrative of Old St. Louis and the Far West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1949), 5, 17, 21, and 141. Kennerly was the son of James Kennerly (the brother of William Clark’s second wife, Harriet Kennerly Radford Clark) and Elise Marie Saugrain Kennerly, which provided an intimate connection between the Clark and Saugrain families. Kennerly wrote that when the captains returned to St. Louis at the end of their journey, “You can be sure they made a call on Dr. Saugrain for he was anxious to hear what good use was made of the scientific instruments he had furnished for the expedition.”[10]Ibid., 17. He noted that Dye had conferred with him as a source for her novel.

Dr. Eldon G. Chuinard insisted that “the handing down of tradition through such reliable resources cannot be discounted . . . “[11]E. G. Chuinard, M.D., The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, Western Frontiersmen Series 19, 1979; Fourth Printing 1989), p. 199. He offered additional support for the theory that Saugrain supplied the explorers with thermometers: “In view of the well-established fact that Dr. Saugrain had been making thermometers and barometers at Gallipolis a decade earlier, it is reasonable to expect he provided Lewis and Clark with additional thermometers . . . “[12]Chuinard, 204.

Chuinard also called attention to an intensive analysis of the Saugrain tradition by Edmond Meany, a wellknown history professor at the University of Washington. Meany’s work is perhaps the most objective critique of the entire mystery surrounding the thermometers. He pursued every possible lead in newspapers, conducted interviews with interested scholars, and explored family traditions, as well as Dye’s correspondence. Meany determined that “family tradition abundant and persistent through three generations must be largely depended upon in lieu of the scant written or printed contemporaneous records” and that “Dr. Saugrain did supply the Lewis and Clark Expedition with a homemade thermometer, some experimental Lucifer matches and perhaps medicine.”[13]Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931), 300–305 and 311.

It is, of course, possible that Dye fabricated the vivid scene of Saugrain scraping his wife’s mirror. For some, the story reads like a serio-comic scenario from a nineteenth-century opera. Yet, it provoked enough curiosity to enlist scholarly attention from no less a figure than Reuben Gold Thwaites, who at the time was engaged in producing his edition of the Lewis and Clark journals. Thwaites once said, in tribute to Dye, that she “has contributed most liberally from the surprisingly rich story of historical materials which, with remarkable enterprise and perseverance, she has accumulated during her preparation for the writing of The Conquest; her persistent helpfulness has placed the Editor [i.e. Thwaites] under unusual obligations.”[14]Meany, 302.

It is certain that Dye relied heavily on her sources, particularly grandsons of William Clark and their widows, documents and family traditions and descendants of Saugrain. Meany considered that “the absence of [specific] citations to her authorities is undoubtedly the main reason why her book was not taken more seriously by subsequent writers.”[15]Meany, 304–305.

In correspondence with Meany, Dye acknowledged this lack of citations, stating, “The Saugrain matter was found in the libraries and historical collections of St. Louis and in newspaper accounts of Dr. Saugrain.”[16]Ibid.

Skeptics

Jackson and Moulton, foremost amongst Lewis and Clark scholars, did not find the Saugrain theory credible. Jackson believed it “not likely” that Saugrain made thermometers for the explorers[17]Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:75n1. and Gary Moulton believed the Saugrain theory was “probably untrue.”[18]Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:243–244n9.

The author of this essay, however, prefers to consider the story as undocumented rather than necessarily “untrue.” The single temperature reading on Aug. 25, 1804, does not rule out the possibility that an additional thermometer could have been discovered in storage following the storm.

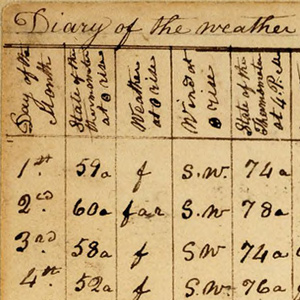

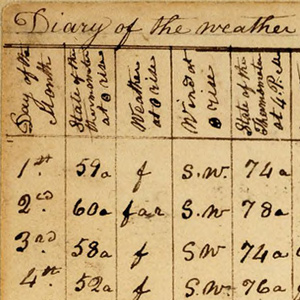

The experiments described in Lewis’s weather diary[19]Moulton, 168–172, with particular emphasis on 169 and 172n4. concerning his notes of reference for January 1804 revealed that he found errors in the Fahrenheit thermometer of 11 degrees below the actual temperature. (Clark noted a difference of eight degrees.) It is curious that such imprecision could be found in a thermometer made by an expert vendor from Philadelphia. This questionable reliability argues in favor of a homemade instrument, pointing to a Saugrain thermometer. Lewis’s experiment wasn’t necessarily conducted with the Donegan Philadelphia instrument mentioned by Clark on 3 January 1804, though Moulton states that Clark’s mention of this thermometer dispels the theory that Saugrain made thermometers for Lewis and Clark.[20]Moulton, 145–147, including note n1.

For some readers, the reference to “Ferenheit” in Lewis’s “Remarks on the Thermometer”[21]Moulton, 2:168–172. may not support a maker of French origin such as Saugrain. Benjamin Franklin noted in 1786, “The French use Reaumur’s, the English Fahrenheit’s.”[22]Leonard W. Labaree, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, copyright 1959 by the American Philosophical Society), 11:281–282. Saugrain had visited Franklin several times and they must have discussed Franklin’s own formula for calculating equivalent readings between the two temperature scales.

Further, Saugrain had been selling instruments to Americans in the Ohio valley region a decade before Lewis and Clark arrived in the area. His buyers would have preferred the Anglo-American Fahrenheit scale. In other words, a Saugrain thermometer could qualify just as well as the Donegan instrument for Lewis’s error-testing experiment.

Thus, to summarize concerning the thermometer’s provenance, the Philadelphia theory cannot be documented and rests on conjecture. The Saugrain theory, although undocumented, is based on recurrent family tradition. Meanwhile, as time passed, the saga of the Corps of Discovery assumed the proportions of a national epic. Epic stories invariably are enhanced, as has occurred with the account of Saugrain’s Parisian mirror being converted into glass-blown tubes filled with mercury. Whether truth or myth, the theory nevertheless persists—a tradition not to be casually set aside.

Related Pages

How did the Indians, expedition cooks, and the hunters make fire? Several methods were used.

In 1804 and in the presence of the Lewis and Clark expedition the little village, built and designed to be an outpost of the fur trade, shed its ambiguous Spanish-French parentage and took on full American citizenship.

May 20, 1804

Sunday in St. Charles

Lewis and a delegation of distinguished citizens leave St. Louis. During a thunderstorm, they shelter in a little cabin. Already in St. Charles, many of the enlisted men attend Catholic mass.

President Jefferson naturally was curious about weather conditions in the newly acquired expanse of Louisiana, and weather observations were on the long list of assignments for his exploring team. Jefferson instructed Lewis to record climate data observed on the trip.

Notes

| ↑1 | Robert R. Hunt, “Of Thermometers and Temperatures on the Lewis and Clark Expedition”, We Proceeded On, November 2007, Volume 33, No. 4, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided at https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol33no4.pdf#page=17. Additional text by Robert Hunt from his article on this site, Making Fire, have been added. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931), p. 309, n. 24, citing W.V. Byars, The First Scientist in the Mississippi Valley, (pamphlet), pp. 14-15. |

| ↑3 | Saugrain de Vigni, Antoine Francois, 1783-1821, L’Odysee Americaine d’une Famille Francaise {par} le docteur Antoine Saugraine; H. Foure Selter, ed. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1936), p.33. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., pp. 3-67. |

| ↑5 | Meany, p. 310. |

| ↑6 | Eva Emery Dye, The Conquest: The True Story of Lewis and Clark (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Company, 1902), 157–158. |

| ↑7 | Doane Robinson, “Lewis and Clark in South Dakota,” South Dakota Historical Collections 9, (1918), 557; John Bakeless, Lewis & Clark, Partners in Discovery (New York: William Morrow & Company, 194 7), 110; and Drake Will, “L & C: Westering Physicians,” Montana Magazine of Western History, Vol. xxi, No. 4 (Autumn 1971), 9. |

| ↑8 | L’Odysee Americaine, 24–29. Brackenridge is quoted at length, referencing “papers concerning Gallipolis belonging to the Cincinnati Historical Society.” |

| ↑9 | William Clark Kennerly as told to Elizabeth Russell, Persimmon Hill, A Narrative of Old St. Louis and the Far West (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1949), 5, 17, 21, and 141. |

| ↑10 | Ibid., 17. |

| ↑11 | E. G. Chuinard, M.D., The Medical Aspects of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, Western Frontiersmen Series 19, 1979; Fourth Printing 1989), p. 199. |

| ↑12 | Chuinard, 204. |

| ↑13 | Edmond S. Meany, “Dr. Saugrain Helped Lewis and Clark,” The Washington Historical Quarterly, Vol. 22 (October 1931), 300–305 and 311. |

| ↑14 | Meany, 302. |

| ↑15 | Meany, 304–305. |

| ↑16 | Ibid. |

| ↑17 | Donald Jackson, ed. Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:75n1. |

| ↑18 | Gary E. Moulton, ed., The Journals of the Lewis & Clark Expedition, 13 volumes (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1983-2001), 2:243–244n9. |

| ↑19 | Moulton, 168–172, with particular emphasis on 169 and 172n4. |

| ↑20 | Moulton, 145–147, including note n1. |

| ↑21 | Moulton, 2:168–172. |

| ↑22 | Leonard W. Labaree, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven: Yale University Press, copyright 1959 by the American Philosophical Society), 11:281–282. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.