Lewis’s education started in Sunday school and continued through his adult years under the guidance of the enlightened Thomas Jefferson.

If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.

Sunday School

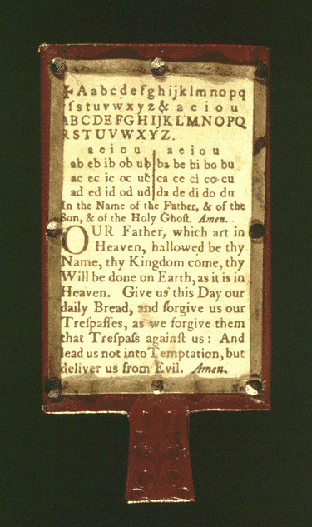

On a single piece of paper measuring approximately 3½ by 2½ inches, are printed, from upper left, a Greek cross representing Christ; the alphabet in lower-case letters followed by an ampersand and the five vowels; and the alphabet in capital letters. To illustrate the various sounds of the vowels they are presented in a syllabarium consisting of fifteen syllables ending with b, c, and d and fifteen more beginning with the same three consonants. The Benediction or Blessing is followed by the Lord’s Prayer.

The page is mounted on a board, which has a handle small enough to fit a tiny hand. A very thin transparent leaf carefully shaved from a cow’s horn—hence the name of the “book”—is tacked over the paper to protect it from grubby young fingers. Hornbooks were made in various sizes, some as large as five by nine inches.

Public education was initiated in England in 1780 by the Anglican Church, after the mechanization of textile and other manufactures began to challenge established socioeconomic and cultural values. The pupils were boys from poor families, who spent six dawn-to-dusk days every week laboring in factories. In response to warnings from conservative critics that educating poor children would eventually foment revolution, the Church held that its goal was to teach them to read and write, in order to enhance their mental skills and specifically enable them to study the Bible, which would divert them from lives of crime on their only day off in the week, Sunday.

The beginnings of education in America date from 1606, when Franciscan missionaries opened their first school in St. Augustine, Florida, to teach children reading, writing, and Church doctrine. In New Orleans, a Franciscan school for boys opened in 1718, and an Ursuline school for girls in 1727.[1]http://www.ncea.org/about/historicalOverviewofCatholicSchoolsInAmerica.asp (accessed on 26 April 2008). Jesuit missionaries established a similar school in Maryland in 1677. Religious education in the New England Colonies had begun in various Protestant parishes as early as the 1640’s. The first interdenominational Sunday School was established in Philadelphia in 1791. The Sunday or Church School movement in the Protestant churches expanded rapidly throughout the U.S. during the second half of the 19th century. In every case, the basic textbook was the Holy Bible along with some sort of catechism that focused on sectarian doctrines. These were studied, read aloud, and memorized in often intimate social settings, which served to imbed religious values into the moral, social and political fabric of every community.

Jefferson’s Ideals

Thomas Jefferson, wary of the risks of entrusting the general education of all citizens to any church, and consistent with his ideal of universal suffrage, proposed in his State of the Union Address, 2 December 1806, a constitutional amendment placing education “among the articles of public care.”[2]Roy J. Honeywell, The Educational Work of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Russel & Russel, 1964), 63. Jefferson, as cited by Padover, lays out four points promoting public education:

- That democracy cannot long exist without Enlightenment.

- That it cannot function without wise and honest officials.

- That talent and virtue, needed in a free society, should be educated regardless of wealth, birth or other accidental condition.

- That the children of the poor must be thus educated at common expense.[3]Thomas Jefferson as cited in Saul K. Padover, Jefferson: A Great American’s Life and Ideas (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1952), 43.

Education for the Young Gentleman

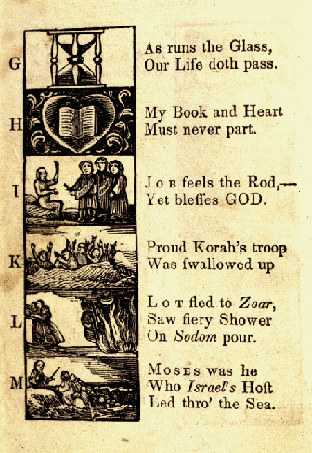

Page from a New England Primer

Courtesy of the Elizabeth Ball Collection, Lilly Library, Indiana University.

The first New England Primer (pronounced with a short i), sometimes called the “Little Bible” of New England, was compiled by Benjamin Harris, an English bookseller and Dissenter who emigrated to Boston, Massachusetts in 1686 to escape the reign of England’s last Catholic monarch, James II. It served as the principal elementary American schoolbook from the Colonial era on, appearing in more than 360 editions by 1830. Thousands of copies were still in circulation during the next twenty years, and some are said to have been used in isolated communities during the early 20th century, still disseminating the racist, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic convictions that were consistent with its Puritan origins.

The primer, typically 90 pages long, opened with the same elements as a hornbook, and often continued with short two-line rhymed verses that explained related drawings, which together were calculated to help a child learn to read. The subjects were chiefly Biblical lessons and moralities, mixed with scenes from a child’s range of experiences. A picture of Adam and Eve beside an apple tree entwined by a serpent was explained in six easy words: “In Adam’s fall/We sinned all.” A drawing of a cat chasing a mouse was paired with “The Cat doth play/And after slay.” Perhaps the most endearing and enduring verse ever to appear in a New England Primer was the child’s prayer:

Now I lay me down to sleep,

I pray the Lord my soul to keep;

Should I die before I wake,

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

At the level of power and privilege, especially in the southern coastal colony-states, the male heirs of plantation owners grew up in an education system that served unique opportunities and expectations. It consisted of three components: the acquisition of basic literacy; the largely oral and experiential medium of popular culture; and a varied library of great books. The basics of common literacy were introduced at the domestic level, with the Bible as the principal source and model. After the rudiments were acquired, the Bible continued to serve as a textbook and workshop for oratory, even among the children of Deists. A larger educational arena was the family’s plantation itself, the maintenance of which involved a number of distinct disciplines required for land management and slave proprietorship.

Land management introduced the pupil to the practical aspects of natural history. Jefferson recalled Lewis’s “talent for observation, which had led him to an accurate knowledge of the plants and animals of his own country, would have distinguished him as a farmer.” Even hunting was more than a landowner’s sport; fox-hunting, for example, was a means of managing a persistent agricultural pest. Thomas Jefferson recalled that at age eight, Meriwether:

. . . habitually went out, in the dead of night, alone with his dogs, into the forest to hunt the raccoon and the opossum, which, seeking their food in the night, can then only be taken. In this exercise, no season or circumstance could obstruct his purpose—plunging through the winter’s snows and frozen streams in pursuit of his object.[4]A. A. Lipscomb and A. E. Bergh, eds., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson Washington, 1903), XVIII:142

That was requisite training for any future plantation owner. It would also have given him practice in a skill he would need in the Army, the ability to load his firelock quickly in the dark.

Lewis’s Childhood Education

In the letter that Thomas Jefferson wrote as an introduction to Nicholas Biddle‘s paraphrase of the captains’ journals, he sketched Lewis’s educational background beginning with the tutelage of his mother—”a Virginia lady of the patrician breed, a benevolent family autocrat”[5]John Bakeless, Lewis and Clark: Partners in Discovery (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1947), 15.—framed by regular hunting forays at all hours of the night and day, in all seasons.

At age thirteen he began his formal schooling in mathematics, history, geography, and both Classic and modern languages, studying for two years under the Parson Matthew Maury at Albermarle. After an unrewarding year with the “atrabilious”—melancholy and peevish—physician, Charles Everitt, Lewis spent two apparently satisfying years with the Presbyterian minister and Episcopal clergyman James Waddell.

During his years in school Lewis was, as his classmate Peachy Gilmer recalled:

. . . always remarkable for perseverance which in the early period of his life seemed nothing more than obstinacy in pursuing the trifles that employ that age: a martial temper: a great steadiness of purpose, self-possession, and undaunted courage. His person was stiff and without grace, bow legged, awkward, formal and almost without flexibility: his face was comely & by many considered handsome. It bore to my vision a very Strong resemblance to Buonaparte in the figure on horseback.[6]Richard Beale Davis, Francis Walker Gilmer: Life and Learning in Jefferson’s Virginia: A Study in Virginia Literary Culture in the First Quarter of the Nineteenth Century (Richmond, VA: The … Continue reading

Early American Spelling

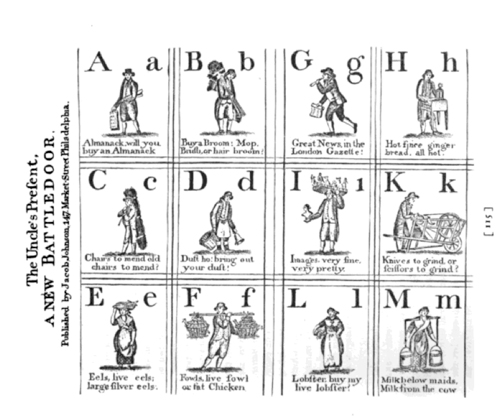

Battledore, Boston, 1844

Courtesy of the Elizabeth Ball Collection, Lilly Library, Indiana University

Among the various primary schoolbooks that competed for the early market was the Battledore, which resembled the paddle that was used in the game of battledore and shuttlecock. Like the Hornbook, Battledores came in various sizes and shapes. Originally it was meant to serve both as a spelling-book and a toy. One cheap variation was printed on both sides of a card that folded in the middle, with a flap to close it. Battledores of various descriptions were popular until the middle of the nineteenth century.[7]http://www.iupui.edu/~engwft/battledore.htm (accessed 24 May 2008).

With his highly successful “blue-backed speller,” Noah Webster’s objective, indeed, his overriding mission in life, was to standardize spelling, usage, and pronunciation in order to consolidate the multifarious, conflicting habits of speech and writing that divided the American citizenry at the turn of the nineteenth century. Webster’s missionary zeal was aroused by the epiphany he underwent in 1782, at an encampment of Revolutionary War soldiers awaiting disbandment. Harlow Giles Unger has summarized Webster’s experience:

Instead of the joyous celebrations he expected among a newly independent people, he heard a dizzying cacophony of languages and accents—Dutch, French, German, Swedish, Gaelic, and varieties of English that the Connecticut Calvinist [Webster himself] had never heard before: the muddy drawls of the rural South, the gargled grunts of Philadelphia Negroes; and the clipped utterances of militiamen from the northern reaches of New Hampshire. He could not understand them, and the sporadic fights he saw told him that many of them could not understand one another, either. Far from producing unity, the independence for which they had fought so long and hard had turned them into a nasty, squalling mob. Webster had come expecting warmth and mutual affection between his countrymen but found only strangers thrashing about in a raging sea of anarchy.[8]Harlow Giles Unger, Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998), 44.

He sought to teach Americans a simplified spelling by omitting superfluous vowels and consonants. He substituted s for the British c in certain words, such as defense, and adopted the more obvious phonetic spelling of center over centre. Webster hewed to a simpler, more logical spelling. The result, he believed, would be consistency in pronunciation in everyday speech, which would lead to a “federal language” of the people, corresponding to the democracy of their government.

The first edition of Webster’s remarkably successful spelling-book, published in 1783, was titled A Grammatical Institute of the English Language; he renamed it in 1787 as The American Spelling Book. It was “a tiny book for tiny hands”—120 pages, six and a quarter inches long and roughly three and one-half inches wide. When it first appeared, Meriwether Lewis was nine years old, Clark thirteen. Lewis might have learned something from it, perhaps belatedly and incompletely—his “musquetoe” corresponds with Webster’s preference—but it is more likely that he learned to read and spell from Thomas Dilworth’s New Guide to the English Tongue, first published in England in 1740, and in the Colonies by Benjamin Franklin seven years later.

Despite its “monstrous absurdities,” Dilworth’s was the standard primer in America until the end of the eighteenth century.[9]E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 226-31. Otherwise, Lewis’s writing may merely reflect the British backgrounds of his teachers—the redundant l in “traveller,” for example, and the superfluous u in colour, for example. The similar habits of Gass, Whitehouse and Ordway may reflect either a British influence in their own elementary education, or the authority of Lewis’s oversight of their journal-keeping.

Lewis’s Adult Education

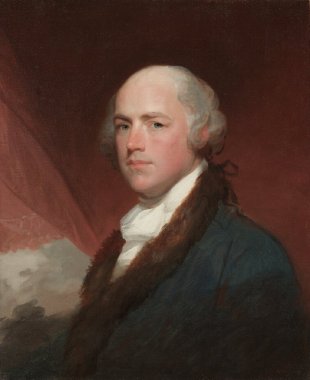

Wilson Cary Nicholas, 1761–1820

by Gilbert Stuart, 1805

Original source: Cleveland Museum of Art. The photo reproduction is in the public domain.

Wilson Cary Nicholas was one of eight learned men that likely influenced Lewis during his tenure as President Thomas Jefferson’s secretary. By that time, Nicholas had already helped frame the United State Constitution, had been a lieutenant in the American Revolution, served in the State house of delegates, and was a member of the United States Senate. Later, he was president of the Second Bank of the United States. After his death, he was interred at Jefferson’s Monticello.

In his eighteenth year, his step-father having died the previous year, 1791, he began an obligatory practicum in agriculture as manager of the family’s plantation, and continued to expand his appreciation for natural history, as most rural gentlemen’s sons were expected to do. However, Jefferson wrote, at age twenty, “yielding to the ardour of youth, and a passion for more dazzling pursuits, he engaged as a volunteer in the body of militia which were called out by General Washington” to deal with the so-called Whiskey Rebellion on the western frontier. Jefferson described this period forward in a letter to Nicholas Biddle:

During the same year he was appointed lieutenant in the U.S. army. In his twenty-third year he was promoted to a Captaincy and returned to Albemarle to recruit. He again joined the army and acted as paymaster until he was made private secretary to the President.[10]Jefferson to Paul Allen, Jackson, Letters, 2:587–88 and Biographical Sketch of Lewis, Jackson, 594.

As Jefferson’s secretary, two important modes of continuing education were available to him until end of 1802 when he began preparations for the expedition. First, there were the occasional gatherings of the intellectual power-brokers of Virginia. Peachy Gilmer listed nine members of Jefferson’s circle, including:

- Thomas Mann Randolph; Jefferson’s son-in-law, Revolutionary War veteran, and prominent legislator

- Colonel Wilson Cary Nicholas, Revolutionary War veteran, U.S. Senator

- Peter Carr, president of the board of trustees of the Albemarle Academy

- Dabney Carr, lawyer and justice of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals

- Benjamin Franklin Bache, Benjamin Franklin’s grandson, journalist, founder of the Philadelphia Aurora

This circle also included, according to Gilmer, “frequent strangers and foreigners attracted by Mr. Jefferson, who “formed the most accomplished and elegant society that has been anywhere, at any time, within my knowledge, in Virginia.”[11]Davis.

Second, there were books that Lewis would likely have considered must-reads. Knowing what titles were most commonly found in gentlemen’s libraries, and in some instances sales figures for certain volumes, it is possible speculate on what he might have read:

- Scottish author Hugh Blair’s famous Lectures on Rhetoric (1783) for guidance in composition, aesthetic theory and oratory.

- Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia, first privately printed in Paris in the U.S. in 1788, was in high demand.

- Works by the Scottish essayist Tobias Smollett (1721-1771) were very popular in America.

- Poems of Alexander Pope (1788-1844) were often quoted by American writers.

- Gibbon’s History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (6 vols., 1776-88) was common.

- James Cook’s Journals . . . and Alexander Mackenzie‘s 1801 journal, Alexander Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal . . . in the years 1789 and 1793 were likely present.

- Letters to His Son by the Earl of Chesterfield on the Fine Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman, written between 1746 and 1771, was common to the Virginian library of the time.

Lewis’s Continuing Education

The qualities of Meriwether Lewis, coupled with his childhood and young-adult education gave Thomas Jefferson the impression that he “could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprize to him. To fill up the measure desired, he wanted nothing but a greater familiarity with the technical language of the natural sciences, and readiness in the astronomical observations necessary for the geography of his route.”[12]Jefferson to Paul Allen, Jackson, 2:588. That education was provided by Lewis’s friends and mentors soon after Lewis arrived in Philadelphia in 1802 including Robert Patterson‘s Astronomy Notebook.

Other Sources

George Emery Littlefield, Early Schools and School-Books of New England (Boston: The Club of Odd Volumes, 1904), 110-116.

Isaac Llewelyn Rhys, The Transformation of Virginia, 1740-1790 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982), 124-135.

Travels to the Source of the Missouri River and Across the American Continent to the Pacific Ocean (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1814), ix.

This article was nearing completion when Joseph Mussulman passed away. Based on personal discussions with the original author and using his original notes and files, the editor presents this article in a completed form.

—Kristopher Townsend, Ed.

Notes

| ↑1 | http://www.ncea.org/about/historicalOverviewofCatholicSchoolsInAmerica.asp (accessed on 26 April 2008). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Roy J. Honeywell, The Educational Work of Thomas Jefferson (New York: Russel & Russel, 1964), 63. |

| ↑3 | Thomas Jefferson as cited in Saul K. Padover, Jefferson: A Great American’s Life and Ideas (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1952), 43. |

| ↑4 | A. A. Lipscomb and A. E. Bergh, eds., The Writings of Thomas Jefferson Washington, 1903), XVIII:142 |

| ↑5 | John Bakeless, Lewis and Clark: Partners in Discovery (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1947), 15. |

| ↑6 | Richard Beale Davis, Francis Walker Gilmer: Life and Learning in Jefferson’s Virginia: A Study in Virginia Literary Culture in the First Quarter of the Nineteenth Century (Richmond, VA: The Dietz Press, 1939). |

| ↑7 | http://www.iupui.edu/~engwft/battledore.htm (accessed 24 May 2008). |

| ↑8 | Harlow Giles Unger, Noah Webster: The Life and Times of an American Patriot (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998), 44. |

| ↑9 | E. Jennifer Monaghan, Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2005), 226-31. |

| ↑10 | Jefferson to Paul Allen, Jackson, Letters, 2:587–88 and Biographical Sketch of Lewis, Jackson, 594. |

| ↑11 | Davis. |

| ↑12 | Jefferson to Paul Allen, Jackson, 2:588. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.