Editor’s Note

With neither France, Spain, nor the United States knowing just where the Missouri River flowed, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was seen by the Spanish as an illegal trespass on their sovereign territory. This triggered a military-backed opposition with no less than four attempts to “arrest Merry” and his band. In August 1804, Dehault Delassus, the former Spanish Governor of Upper Louisiana in St. Louis, warned:

I am of the opinion, that if the greatest precautions are not taken to stop the contraband, within a short time, one will see descending the Missouri, instead of furs, silver from the Mexican mines [which will] arrive in this post in abundance.

It is also said that the voyage of Captain Lewis (of which I have informed Your Excellency at the time) is directing itself towards New Mexico; that his plan to discover the Pacific Ocean was no more than a pretext.”[1]Before Lewis and Clark: Documents Illustrating the History of the Missouri 1785–1804, ed. A. P. Nasatir (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 745.

The following is an extract from Dan Sturdevant and Jay J. Buckley, “Spanish Attempts to Apprehend Lewis and Clark”, We Proceeded On, February 2019, Volume 45, No. 1, the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation. The original, full-length article is provided https://lewisandclark.org/wpo/pdf/vol45no1.pdf#page=20.

Above: Drouillard casually observes as a Spanish soldier in white has a discussion with Meriwether Lewis. See November 30, 1803.

Introduction

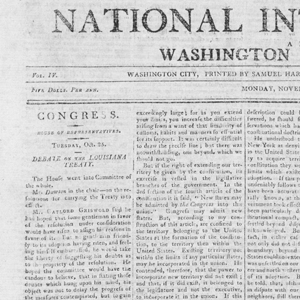

No country knew the actual boundaries of land included in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Article One of the treaty provided a vague description of the transferred land: “the colony or province of Louisiana, with the same extent that it now has in the hands of Spain and that it had when France possessed it.”[2]See https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/louistxt.html. There was similar language in the 1800 Treaty of San Ildefonso and also in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau. Accessed 16 … Continue reading President Thomas Jefferson believed “the boundaries of interior Louisiana are the high lands inclosing all the waters which run into the Mississippi or Missouri directly or indirectly, with a greater breadth on the gulph [sic] of Mexico.”[3]Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:137. See also, Jefferson to Lewis, Washington, … Continue reading In contrast, Spanish boundary commissioners recommended a much smaller definition of the Louisiana Territory, limiting it to lands beginning 120 miles west of St. Louis and thence a line south from there (now the middle of the State of Missouri) through what is now central Arkansas, Natchitoches, Louisiana, and south to the Gulf of Mexico.[4]David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 293. Spanish officers felt it fully in their right to arrest American explorers because the purchase boundary had never sufficiently been defined. Moreover, Spanish Ambassador to the United States Casa Irujo turned down Jefferson’s December 1802 request for a passport for Lewis. On 12 March 1805, the Spanish complained to Secretary of State James Madison that the Lewis and Clark Expedition was in violation of the status quo in the disputed territory, “since its true boundaries had yet to be established.”[5]Casa Irujo to Madison, Washington, DC, 12 March 1805, SpAHN (Estado 5542). A copy formerly in Department of State is cited by Isaac J. Cox, The Early Explorations of Louisiana (Cincinnati: Ohio … Continue reading

Santa Fe, New Mexico—the Spanish capital of New Mexico since 1609—remained a relatively small village, “a collection of dusty adobe homes and huts with a population of roughly 5,000.”[6]Jay H. Buckley, “Pike as a Forgotten and Misunderstood Explorer,” in Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson and the Opening of the American West, Matthew L. Harris and Jay H. Buckley, eds. … Continue reading Although it was located some 850 miles from its closest point to the Missouri River, Spanish officials presumed Santa Fe a suitable launching point for expeditions tasked with apprehending American exploratory groups such as Lewis and Clark.

Pierre (Spanish called him Pedro) Vial proved the obvious choice to lead this intercept expedition. Vial perhaps knew more about the geography and indigenous nations of the Spanish Borderlands of the Great Plains than any other European. He had “traveled the wilderness around Santa Fe, San Antonio, Natchitoches, and St. Louis, seemingly at will. It was something of a feat to journey safely among Apaches, Utes, Kiowas, Comanches, Kansas, Osages, Otos, Missourias, Iowas, Sioux, Arapahos, Pawnees and other tribes known to be indefatigable gatherers of scalps—and not lose one’s own hair.”[7]Noel M. Loomis, and Abraham Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967), xvi.

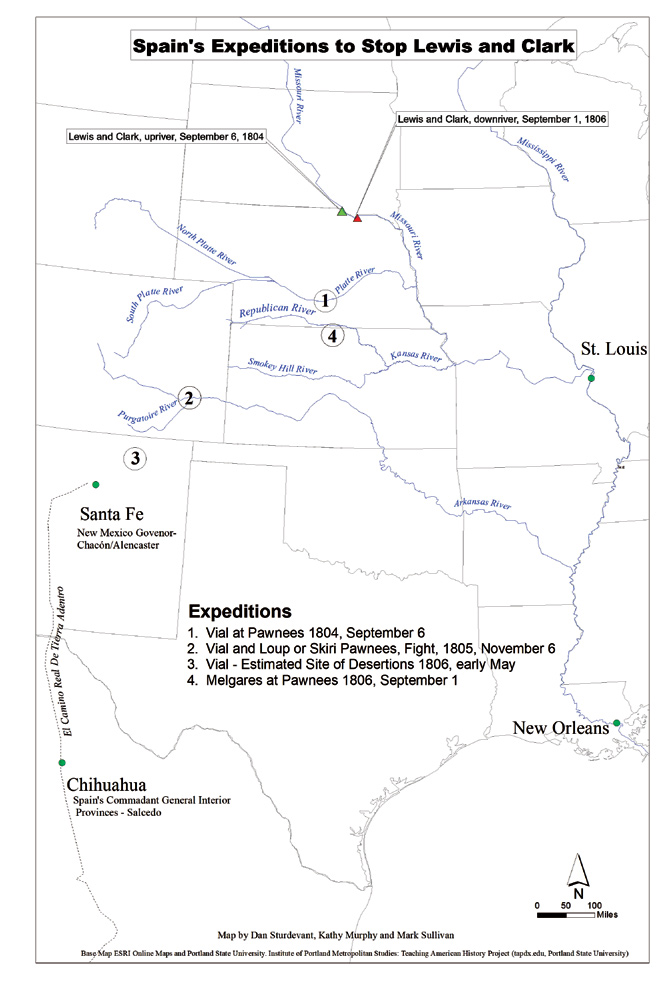

Spain’s Expeditions to Stop Lewis and Clark

by Dan Sturdevant, Kathy Murphy, and Mark Sullivan

Base Map ESRI Online Maps and Portland State University. Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies: Teaching American History Project (tapdx.edu Portland State University).

Above: Drouillard casually observes as a Spanish soldier in white has a discussion with Meriwether Lewis. See November 30, 1803.

First Expedition

Planning the initial expedition to intercept Lewis and Clark took Governor Chacón, Pedro Vial, and his traveling companion Jose Jarvet ten weeks to complete. Vial and Jarvet embarked with 32 men on 1 August 1804, and were joined by 20 more a few days later. Traveling rapidly, the party followed the Purgatoire River to the Arkansas River. Vial and Javet arrived at a Pawnee village in today’s south central Nebraska, about 150 miles west of the Missouri River, on 6 September 1804. This marked the eastern terminus of this expedition. “A great many of their [Native American] captains came to meet us,” Vial recorded. “They gave us a great reception . . . I learned how the Americans had taken over the government . . . that numerous parties of [Euro-Americans] were coming very loaded with articles for all the nations of the Misury . . . . In every village they [the Americans] pass, large gifts are made to all chiefs and principal men and said chiefs are induced to surrender medals and patents in their possessions, given by the Spanish government. [I told the Pawnee they] still do not know the Americans but in the future they will.”[8]Diario de Dn. Pedro Vial a la nacion Panana, Santa Fe, 23 November 1804, SpAGI (Aud. Guad.398) fol. 3v-4, as translated and cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 463.

Vial was unable to determine among these various trading parties which one Lewis and Clark might have been. In truth, Lewis and Clark had already ascended the Missouri to present-day South Dakota. Unable to ascertain Lewis and Clark’s particular location or determine when they had passed, Vial did not think it prudent to continue on to the Missouri River itself. Convincing some Pawnees and Otos to travel with him, Vial’s party returned to Santa Fe two weeks later.

Second Expedition

After the Vial expedition returned to Santa Fe, Governor Chacón was replaced (reportedly for health reasons) by Joaquin del Real Alencaster. A Spanish Royal Order dated 5 June 1805, required the continuation of the mission to capture Lewis and Clark.[9]Royal Order 5 June 1805, NmSRC (Span. Arch. 1841a); as cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 460. Juan Manuel de Salcedo, the last governor of Spanish Louisiana sent that instruction in September to Santa Fe to “Arrest Merry” and to encourage natives to assist Spanish troops in that effort. Louisiana, encouraged New Mexico Governor Real Alencaster to infuse the natives “with a horror [of Americans] . . .in the awareness that they can expect nothing but ejection from their lands . . . [so that] when Captain Merri’s expedition returns . . . they [native nations] will intercept it, apprehending its members.” He continued that “if by this means we could acquire them, considerable advantages would result without our having to use the alternative of stationing troops in spots where the expedition might pass, since perhaps that would cause resentment and agitation among the Indians.”[10]Commandant General Salcedo to New Mexico Governor Real Alencaster, Chihuahua, 9 September 1805, MxMDN, Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 20–21, in Manuscript Division, … Continue reading At the same time, Salcedo was realistic when he wrote in October 1805 to the Mexico City Spanish Viceroy to warn that “it will be impossible to counter all of them, since that [American] government at all appearances is directing a large portion of its attention to these domains [Spain’s Provincias Internas].”[11]Commandant General Salcedo to Inturrigaray, Chihuahua, 6 October 1805, MxAGN, (Prov. Internas 200) fol.269-272. Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 20-21, in Manuscript … Continue reading

Vial’s second expedition left Santa Fe on 14 October 1805, with approximately 106 people. At that time, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was at the other end of the continent, descending the Columbia River, about three weeks east of the river’s mouth at the Pacific Ocean. Heading north from Santa Fe about 310 miles, Vial’s party arrived near the junction of the rivers Purgatoire and Arkansas on 5 November 1805. Vial’s diary noted how fearful they were of an enemy [i.e., Native American] ambush. Apparently this fear was well-placed, for around midnight on 5 November, a group of Pawnees “attacked us in three bands, one [going] for the horses and two for the encampment . . . . They got possession of our supply of goods . . . we rushed them until we threw them into the river, where they burst out in outcries, because of which it is considered some harm was done to them . . . they had no arrows, but all had firearms.”[12]Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 435-36. Without sufficient supplies, Vial had no choice but to return to Santa Fe. King Carlos would not be pleased.

Meanwhile, Governor Alencaster had been awaiting a visit from a Pawnee delegation sometime in the fall of 1805. When the delegation did not come, and he learned of the Pawnee skirmish with Vial’s men, Alencaster interpreted these incidents as evidence that the Pawnees were “in complete agreement and commerce with the Americans.”[13]Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 4 January 1806, NmSRC – State Record Center and Archives, Santa Fe New Mexico (Span. Arch. 1942). Trans. in Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial … Continue reading

Third Expedition

The news that the first two attempts to apprehend the American trespassers (Lewis and Clark) had failed did not sit well with the king. On >12 February 1806, Salcedo received a communication chastising him for the failures.

His Majesty orders me to tell you [Commandant General Salcedo] that he is surprised that you have not kept him informed of progress of the said expeditions; likewise His Majesty desires to know how the said expedition has been permitted in territory of his domains.”[14][Minister of state] to the commandant general of the interior provinces, El Pardo, 12 February 1806, SpAHN (Estado 5542), cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 475.

When the Spanish king reprimands you, you had better try harder, since falling out of favor with the royals is often a career killer. So Salcedo and New Mexico Governor Alencaster in Santa Fe planned a third expedition. Vial’s third expedition left Santa Fe on 24 April 1806, with about 300 men. Unfortunately, the information on this expedition is scanty at best. Loomis and Nasatir write, “With no diary at hand, it appears from the evidence after the fact that Vial’s men deserted, and the expedition was another failure.”[15]Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 446. Later, Salcedo wrote back to Alencaster that he understood from Alencaster’s report that “disobeying the sergeants and corporals in charge of Vial’s . . . expedition, the militia and the Indians named for their escort abandoned it.”[16]Salcedo in Chihuahua to Alencaster in Santa Fe, July 18, 1806. New Mexican Archives, doc. 2001. Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 471. With this disaster, the unfortunate Pedro Vial vanishes from the Spanish records.

Sharitarish (Wicked Chief). Pawnee tribe

by Charles Bird King (1785–1862)

Height: 44.6 cm (17.5 in); Width: 35.1 cm (13.8 in). Courtesy The White House Historical Association, 1962.394.2.

Sharitarish represented the Chawi, or Grand Pawnees, in a delegation visiting United States President James Monroe in 1822. During that trip, he posed for portraitist Charles Bird King. He was the son of Characterish, who persuaded Facundo Melgares to abandon his attempt to stop the Lewis and Clark Expedition in September 1806 and confiscate all their possessions.

Fourth Expedition

Salcedo wrote an order from Chihuahua on 12 April 1806, directing another Spanish expedition leader, Lieutenant Facundo Melgares in Chihuahua, to leave for Santa Fe to lead a new party of 60 men to reconnoiter the “[Red] and Arkansas [Rivers] to watch the [Freeman-Custis][17]“Freeman–Custis” shown in brackets replaces Salcedo’s original “Dunbar.” The 1806 American expedition Salcedo wrote about was later named “Freeman-Custis.” … Continue reading expedition, drive it back, or capture it and take it to Santa Fe.”[18]Salcedo to Real Alencaster, Chihuahua, 12 April 1806, MxMDN, Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 108-109, Cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 477. See also Herbert Eugene … Continue reading By 30 May, New Mexico Governor Alencaster and expedition leader Melgares took authority to expand upon Salcedo’s April 12 order, writing that Melgares was to travel “down the Red River . . . and then go northward to the Arkansas [River] and [north to] the land of the Pawnee, Lobo, and Oto.”[19]Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 30 May 1806, MxMDN (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 148-51. Summarized by Bolton, Guide, 309; Real Alencaster to Salcedo, Santa Fe, 8 … Continue reading

Melgares left Santa Fe around 15 June 1806, with around 600 people, including 100 soldiers, 100 natives (likely Comanches), and 400 militia, and about 2,000 horses and mules.[20]Recruiting 400 men out of Santa Fe area must have comprised the majority of the male population. “The only thing furnished by the government (to the male population recruits) is … Continue reading Much of what we know of Facundo Melgares’ expedition—the fourth and final Spanish attempt to arrest Lewis and Clark—comes from American explorer Zebulon Pike because Melgares’ diary has been lost. Fortunately, Pike recorded in his diary information regarding his communications and interactions with Melgares.[21]Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike; Leo E. Oliva, “Enemies and Friends: Pike and Megares in the Competition for the Great Plains,” in Harris and Buckley, Zebulon Pike,161-84.

Melgares’ large force traveled southeast down the Red River but did not meet the Hunter and Dunbar Expedition, so his force turned north.[22]Another Spanish group did turn back the Hunter and Dunbar expedition and another Spanish force turned back the Freeman and Custis expedition. Jay H. Buckley, “Jeffersonian Explorers in the … Continue reading When asked where Melgares was taking them, he reportedly told his men, “wherever his horse led him.”[23]Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 2:57-58. Melgares’ men threatened to desert, but he circumvented the proposed mutiny by threatening to hang their leader, which apparently worked.

Melgares arrived at the Pawnee villages on the Republican River, southwest of present-day Guide Rock, Nebraska (this location remains disputed), arriving about 1 September 1806. Melgares met the Pawnees there and held council, presenting them with Spanish flags and medals. Melgares did not head east from this location, although he was only 140 miles west of the Missouri River. Chief Characterish later told Pike that he had persuaded Melgares not to travel to the Missouri. The chief declared “that it was the intention of the Spanish troops to have proceeded further towards the Mississippi, but, that he objected to it, and they listened to him and returned.”[24]Pike to General J. Wilkinson, 2 October 1806, in Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 2:150-53. Pike wrote that Melgares “did not proceed on to the execution of his mission with the . . . Mahaws and Kans [who lived closer to the Missouri River], as he represented to me, from the poverty of their horses, and the discontent of his own men.”[25]Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1:324. Pike perceived that great suspicion and discontent “began to arise between the Spaniards and the Indians.”[26]Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1:324.

By the middle of September 1806, Melgares turned around and headed home. At that time, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was in northwest Missouri, closing in on St. Louis. Coming upriver were traders. John Ordway wrote, “Mr. McLanen informed us that the people in general in the United States were concerned about us as they had heard that we were all killed then again they heard that the Spanyards had us in the mines &C.”[27]Gary Moulton, The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 9:361. But Spain did not have the Lewis and Clark men working their silver mines in Chihuahua or anywhere else. And Lewis and Clark had not learned of any Spanish intercept efforts during their journey.

Conclusion

The Spanish made repeated attempts to defend their borderlands and maintain a claim within Louisiana’s disputed boundary. Ultimately, they failed to prevent American expansion and acquisition of the central and southern plains. Summarizing the four Spanish attempts to stop Lewis and Clark, historian Warren Cook wrote, “defending that area by overland sallies from New Mexico was an impossibility . . . . Even so, it is surprising how close the Spanish came to intercepting Lewis and Clark, in 1804, and again in 1806. A matter of several days’ march, in the first and fourth Spanish expeditions, prevented an encounter that could have resulted in a major incident between the two nations.”[28]Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 485.

Cook may have overstated the chances of these Spanish expeditions. Neither Vial nor Melgares knew nor could accurately determine where Lewis and Clark were. The Santa Fe Governors’ ongoing problem with trying to apprehend the Lewis and Clark Expedition was never knowing where the expedition was at any given point in time. Salcedo resolved this timing problem in part by asking Vial to persuade the Native Americans on or near the Missouri River to stop Lewis and Clark. The Spanish, for instance, had a notion that the Americans would be coming down the Missouri in the spring of 1806. The Spanish knew this because Corporal Richard Warfington and a small crew left Fort Mandan and returned the keelboat [the barge] to St. Louis by 20 May 1805, with information that Lewis and Clark were proceeding on to the Missouri’s headwaters and thence to the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River, hoping to return the following year. This was reported in New Orleans. However, no tribe appears to have been willing to set up camp on the Missouri River to wait for Lewis and Clark, who did not descend the Missouri, east of the Pawnee villages, until the fall of 1806.

On the other hand, it was logical for Vial in 1804 to make a decision to march straight north about 160 miles to the Missouri River and hope that Lewis and Clark would still be coming upriver. In 1806, Melgares could have marched straight east about 140 miles to the Missouri River, hoping the Americans would be coming downriver.[29]A Melgares march starting on 2 September from Guide Rock, Nebraska, and straight east to the Missouri River would have taken about 6 or 7 days. This march hypothetically puts Melgares and his men on … Continue reading Given the time and distance, in fact, each one of those strategies might have worked. But how can you blame either Spaniard when neither knew anything about the Americans’ location? Eventually, the western and southern boundary dispute between Spain and the United States was settled by John Quincy Adams and Luis de Onís y Gonzalez-Vara in what is known as the Adams-Onís treaty of 1819, a transcontinental treaty that established the southern boundary of the Louisiana Territory at the Red River.

Related Pages

- The Pawnees -

Although Clark referred to the Pawnee often and included them in the Estimate of the Eastern Indians, the journals do not document any face-to-face encounters.

- James Wilkinson -

James Wilkinson was one of the most duplicitous, avaricious, and altogether corrupt figures in the early history of the United States. At the time of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, he was a paid agent of the Spanish government.

- January 31, 1803 -

In Washington City, the Spanish minister to the United States writes an update on the progress of President Jefferson’s proposal to send an expedition to the Pacific ocean—an act Spain opposes.

- October 4, 1803 -

On or near this date, Lewis leaves Cincinnati for Big Bone Lick where he expects to collect fossils for Thomas Jefferson. Elsewhere, tensions rise between Spain and the United States over Louisiana.

- October 5, 1803 -

Lewis is likely at Big Bone Lick collecting fossils and fellow travelers Thomas Rodney and Nicholas Cresswell describe the diggings that he saw. Elsewhere, the U.S. Army expects problems with Spain.

- November 29, 1803 -

On or after this date at Fort Kaskaskia, the captains learn that the Spanish Governor of Upper Louisiana intends to block the expedition. They select more soldiers and make decisions about their next steps.

- December 7, 1803 -

Lewis travels by land and Clark by river to arrive at Cahokia, Illinois. Lewis meets John Hay and Nicholas Jarrot who help him negotiate with the Spanish Lt. governor of Upper Louisiana.

- December 8, 1803 -

On this or the previous day, Lewis meets with Dehault Delassus, the Spanish Lt. Governor of Upper Louisiana, and all agree that the expedition should spend the winter near Cahokia.

- December 9, 1803 -

While in Cahokia, Lewis receives mail and newspapers sent to him by President Jefferson. In St. Louis, the Spanish Governor of Upper Louisiana updates his superiors about the nature of Lewis's mission.

- January 17, 1804 -

At Wood River, the thermometer drops below zero and the Missouri runs with ice. In Washington City, the Spanish Minister proposes that the Americans leave the west side of the Mississippi to the Indians.

- January 28, 1804 -

In his field notes, Clark records each hour at winter camp across from the mouth of the Missouri. The Spanish governor of Louisiana formally allows the expedition to proceed up the Missouri River.

- March 24, 1804 -

At winter camp on the Wood River, Clark sends out letters. Sometime this month, the Commanding General of the U.S. Army secretly advises Spanish officials to stop the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

- March 30, 1804 -

At winter camp on the Wood River, the orders of yesterday’s military court are read. In New Orleans, Spanish Commissioner Casa Calvo asks that the Lewis and Clark Expedition be stopped by military arrest.

- May 8, 1804 -

The barge and a pirogue are taken for a shakedown cruise a few miles up the Mississippi. In New Orleans, the former governor of Spanish Louisiana urges his Commandant General to arrest Meriwether Lewis.

- May 28, 1804 -

At the Gasconade River, the expedition hunts and dries wet cargo. Having met with Captains Lewis and Clark on 25 May, trader Régis Loisel is now in St. Louis warning Spain of American encroachments.

- The Freeman-Custis Expedition -

Narrated in both English and Spanish, Daniel Flores tells the story of a parallel, southern exploration now nearly forgotten.

- August 20, 1804 -

The expedition stops near present Sioux City, Iowa to bury Sgt. Floyd with a full military ceremony. Elsewhere, Salcedo reports on several American expeditions in contested Spanish territory.

- September 15, 1804 -

Moving up the Missouri below present Oacoma, South Dakota, the expedition passes the creek where Shannon had waited to be rescued. Gass and Reubin Field spend the night twelve miles up the White River.

- January 17, 1805 -

With the thermometer dropping to -12°F, there is little activity at Fort Mandan and only a few Knife River villagers visit. In Spain, King Charles IV authorizes the arrest of Lewis and his expedition.

- March 12, 1805 -

At Fort Mandan, Hidatsa interpreter Toussaint Charbonneau quits, and in Washington City, Spanish Minister Yrujo complains that Jefferson's western expeditions are intruding on Spanish territory.

- September 9, 1805 -

The expedition reaches Travelers' Rest, a well-used camping area near present Lolo, Montana. Their guide, Toby, tells them about the Road to the Buffalo—a good pass heading east to the Missouri River.

- October 11, 1805 -

Between present Clarkston and Almota, Washington, the paddlers navigate numerous Snake River rapids where the Nez Perce and Palouse have established fisheries. The captains notice a curious sweat lodge.

- October 13, 1805 -

To start the day, the non-swimmers portage rifles and scientific equipment while the boatmen navigate a long Snake River rapid. Late in the day, they run a two-mile rapid which "ran like a mill race."

- October 14, 1805 -

After passing a 'ship rock'—Monumental Rock on the Snake River in Washington—Sgt. Ordway‘s canoe gets stuck on a rock and fills with water. They stop for the day and begin drying wet items.

- November 5, 1805 -

After a night made sleepless by noisy waterfowl, the expedition heads down the Columbia. They pass the large village known today as Cathlapotle and encounter various Chinookan People.

- February 12, 1806 -

At Fort Clatsop near present Astoria, Oregon, Lewis describes two species of Oregon grape, and three Clatsop dogs are brought as payment for missing elk meat. In Washington City and Madrid, suspicions grow.

- September 25, 1806 -

After storing botanical and zoological specimens in Pierre Chouteau's St. Louis warehouse, the captains attend a ball. At Christy’s Tavern, eighteen toasts are given in honor of the "Missouri expedition".

Notes

| ↑1 | Before Lewis and Clark: Documents Illustrating the History of the Missouri 1785–1804, ed. A. P. Nasatir (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990), 745. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/louistxt.html. There was similar language in the 1800 Treaty of San Ildefonso and also in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau. Accessed 16 November 2018. |

| ↑3 | Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents: 1783-1854, 2nd ed., ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1978), 1:137. See also, Jefferson to Lewis, Washington, DC, 16 November 1803, DLC (Jefferson Papers). Jefferson must have meant “on the west side of the Mississippi.” See also, Jon Kukla, A Wilderness So Immense: The Louisiana Purchase and the Destiny of America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003). |

| ↑4 | David J. Weber, The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 293. |

| ↑5 | Casa Irujo to Madison, Washington, DC, 12 March 1805, SpAHN (Estado 5542). A copy formerly in Department of State is cited by Isaac J. Cox, The Early Explorations of Louisiana (Cincinnati: Ohio University Press, 1906), 23, 134, as cited in Warren L. Cook, Flood Tide of Empire: Spain and the Pacific Northwest, 1543–1819 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1973), 459. |

| ↑6 | Jay H. Buckley, “Pike as a Forgotten and Misunderstood Explorer,” in Zebulon Pike, Thomas Jefferson and the Opening of the American West, Matthew L. Harris and Jay H. Buckley, eds. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 21-59. |

| ↑7 | Noel M. Loomis, and Abraham Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967), xvi. |

| ↑8 | Diario de Dn. Pedro Vial a la nacion Panana, Santa Fe, 23 November 1804, SpAGI (Aud. Guad.398) fol. 3v-4, as translated and cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 463. |

| ↑9 | Royal Order 5 June 1805, NmSRC (Span. Arch. 1841a); as cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 460. |

| ↑10 | Commandant General Salcedo to New Mexico Governor Real Alencaster, Chihuahua, 9 September 1805, MxMDN, Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 20–21, in Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, (Cunningham Transcripts); Translation. in Donald Jackson, The Journals of Zébulon Montgomery Pike (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), 2:104-08. |

| ↑11 | Commandant General Salcedo to Inturrigaray, Chihuahua, 6 October 1805, MxAGN, (Prov. Internas 200) fol.269-272. Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 20-21, in Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, (Cunningham Transcripts). Translated by and cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 474. |

| ↑12 | Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 435-36. |

| ↑13 | Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 4 January 1806, NmSRC – State Record Center and Archives, Santa Fe New Mexico (Span. Arch. 1942). Trans. in Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 442. |

| ↑14 | [Minister of state] to the commandant general of the interior provinces, El Pardo, 12 February 1806, SpAHN (Estado 5542), cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 475. |

| ↑15 | Loomis and Nasatir, Pedro Vial and the Roads to Santa Fe, 446. |

| ↑16 | Salcedo in Chihuahua to Alencaster in Santa Fe, July 18, 1806. New Mexican Archives, doc. 2001. Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 471. |

| ↑17 | “Freeman–Custis” shown in brackets replaces Salcedo’s original “Dunbar.” The 1806 American expedition Salcedo wrote about was later named “Freeman-Custis.” Dunbar’s name is given to an 1804 expedition in the southwest. |

| ↑18 | Salcedo to Real Alencaster, Chihuahua, 12 April 1806, MxMDN, Archivo de la Biblioteca (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 108-109, Cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 477. See also Herbert Eugene Bolton, Guide to Materials for the History of the United States in the Principal Archives of Mexico (Carnegie Institution of Washington, DC, 1913), 309. |

| ↑19 | Real Alencaster to Commandant General Salcedo, Santa Fe, 30 May 1806, MxMDN (Legajo 1787-1807, Cuaderno 15), fol. 148-51. Summarized by Bolton, Guide, 309; Real Alencaster to Salcedo, Santa Fe, 8 October 1806, MnSRC (Span. Arch. 2022). As cited in Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 477. |

| ↑20 | Recruiting 400 men out of Santa Fe area must have comprised the majority of the male population. “The only thing furnished by the government (to the male population recruits) is ammunition.” Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 2:57-58. |

| ↑21 | Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike; Leo E. Oliva, “Enemies and Friends: Pike and Megares in the Competition for the Great Plains,” in Harris and Buckley, Zebulon Pike,161-84. |

| ↑22 | Another Spanish group did turn back the Hunter and Dunbar expedition and another Spanish force turned back the Freeman and Custis expedition. Jay H. Buckley, “Jeffersonian Explorers in the Trans-Mississippi West: Zebulon Pike in Perspective,” in Harris and Buckley, Zebulon Pike, 101-38. See also Doug Erickson, Jeremy Skinner, and Paul Merchant, eds., Jefferson’s Western Expeditions: Discoveries Made in Exploring the Missouri, Red River, and Washita by Captains Lewis and Clark, Doctor Sibley, William Dunbar (Spokane: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 2004). |

| ↑23 | Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 2:57-58. |

| ↑24 | Pike to General J. Wilkinson, 2 October 1806, in Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 2:150-53. |

| ↑25 | Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1:324. |

| ↑26 | Jackson, The Journals of Zebulon Pike, 1:324. |

| ↑27 | Gary Moulton, The Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986), 9:361. |

| ↑28 | Cook, Flood Tide of Empire, 485. |

| ↑29 | A Melgares march starting on 2 September from Guide Rock, Nebraska, and straight east to the Missouri River would have taken about 6 or 7 days. This march hypothetically puts Melgares and his men on the Missouri River, near today’s Rulo, Nebraska, south of where Lewis and Clark actually were. |

Experience the Lewis and Clark Trail

The Lewis and Clark Trail Experience—our sister site at lewisandclark.travel—connects the world to people and places on the Lewis and Clark Trail.

Discover More

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition: Day by Day by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2018). The story in prose, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals: An American Epic of Discovery (abridged) by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 2003). Selected journal excerpts, 14 May 1804–23 September 1806.

- The Lewis and Clark Journals. by Gary E. Moulton (University of Nebraska Press, 1983–2001). The complete story in 13 volumes.